Factors such as pretreatment, age, patient performance, and comorbidities determine relapse therapy in multiple myeloma. Triple combinations with a proteasome inhibitor and/or an IMID are standard. Antibody therapies also play an important role in myeloma treatment.

In fit patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma, induction treatment followed by consolidative high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplantation (ASZT) is performed. To achieve good disease control over as long a period as possible, consolidation treatment and/or maintenance therapy is followed. The therapeutic goal is a complete, if possible molecular remission. In elderly and/or unfit patients, the focus is on achieving the best possible response to first-line treatment with few side effects and preservation of quality of life.

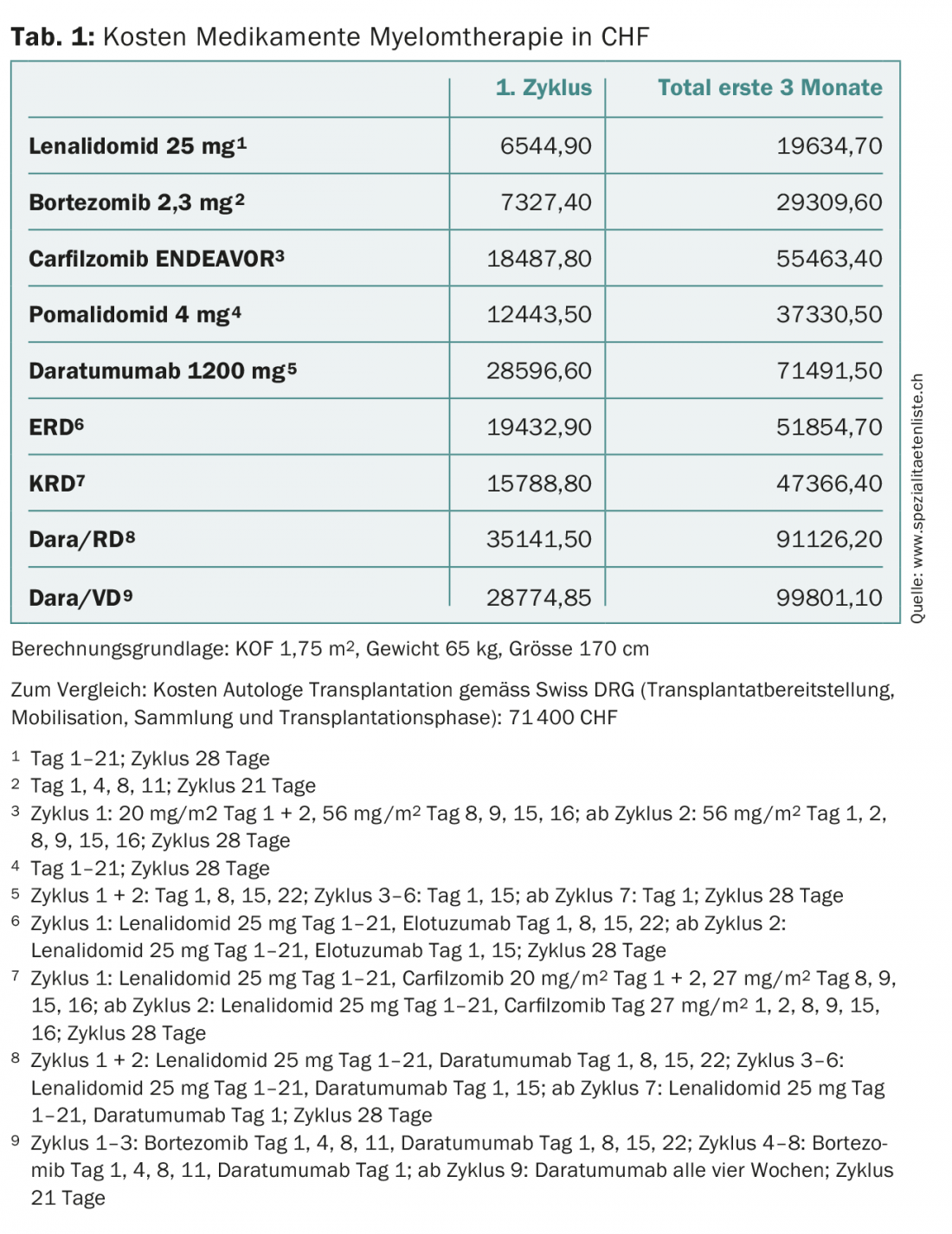

Almost all patients subsequently suffer a recurrence. In this situation, the lenalidomide/dexamethasone (RD) or bortezomib/dexamethasone (VD) combinations were the standard treatments for a long time [1–3]. However, both agents are now widely used in first-line treatment, increasing the number of patients refractory to those drugs. Many new drugs have become available for these patients in recent years. The choice of therapy takes into account previous therapies (change of substance class, response, tolerance), age, ability to perform, comorbidities and, of course, approval in Switzerland. In fit patients with a progression-free period of at least 12 months after a first ASZT, a second ASZT should be considered, as the results after salvage ASZT in such patients are equivalent or superior to those of the most effective triple combinations, with shorter treatment duration and lower overall costs on average (Table 1) [4,5].

First relapse after bortezomib-based therapy.

After bortezomib-based first-line therapy, treatment with lenalidomide/dexamethasone was suggested to patients until a few years ago [1,2]. Today, in the second line, with better progression-free survival (PFS), a three-drug combination should be the focus.

The combination of RD with the SLAMF7 (“signaling lymphocytic activation molecule F7”) monoclonal antibody elotuzumab showed a median PFS of 19.4 months (vs. 14.9 months with RD) in the ELOQUENT-2 trial. A total of 646 patients with a median of two prior therapies were included. Treatment with ERD was continued until progression or unacceptable side effects. The overall response rate (ORR) with ERD was 79% (vs. 66%). Time to next treatment ( TTNT) was prolonged by one year (33 vs. 21 months), and median survival in the ERD group was 43.7 months (vs. 39.6 months). The most common grade 3 or 4 adverse events were hematologic (neutropenia 34% vs. 44% and lymphopenia 77% vs. 49%). The clinical benefits were accompanied by more frequent infections (88% vs. 74%), particularly herpes zoster [6,7]. In Switzerland, the combination of elotuzumab with lenalidomide and dexamethasone (ERD) is approved from the second line of therapy.

As an additional triple therapy, the combination of lenalidomide/dexamethasone together with carfilzomib, a second-generation proteasome inhibitor, is approved starting with the second line of therapy. In the ASPIRE trial, this combination showed a prolongation of median PFS by 8.7 months (26.3 vs. 17.6 months) in 792 patients compared with RD alone. Carfilzomib with RD (KRD) was administered for a maximum of 18 cycles, RD until progression. The ORR was an impressive 87.1% (vs. 66.7%), with a CR rate for KRD of 31.8% (vs. 9.3% in the RD group). The 2-year survival in the KRD group was 73.3% (vs. 65%). Carfilzomib is administered in this combination up to a maximum of 27 mg/m2 twice per week. The side effect rate also regarding neuropathy is comparable. Of particular interest were cardiac problems with carfilzomib: dyspnea (2.8% vs. 1.8%), heart failure (3.8% vs. 1.8%), ischemic heart disease (3.3% vs. 2.1%), hypertension (4.3% vs.1.8%), and acute renal failure (3.3% vs. 3.1%) [8].

First relapse after IMID-based therapy

After IMID-based first-line therapy, proteasome inhibitor-containing therapy is recommended as second-line therapy. The combination of bortezomib/dexamethasone (VD) has traditionally been used [3]. The combination of carfilzomib with dexamethasone (KD) was shown to be more effective in the ENDEAVOR trial. Median PFS was significantly longer at 18.7 vs. 9.4 months vs. VD. 54% of the 929 patients in this study were pretreated with bortezomib, although not refractory. PFS was also longer in these patients by KD, 15.6 vs. 8.1 months. Carfilzomib was administered at the dose of 56 mg/m2 twice a week. The most common adverse events at this dose included anemia (14% vs. 10%), hypertension (9% vs. 3%), thrombocytopenia (8% vs. 9%), and pneumonia (7% vs. 8%), whereas the occurrence of grade 2 or higher polyneuropathies was significantly less common with carfilzomib (6% vs. 32%) [9]. Carfilzomib is not approved in Switzerland at this dosage.

Standard in the first recurrence should be a triple combination if possible. A rather favorable combination is bortezomib/dexamethasone in combination with cyclophosphamide (VCD or CyBorD). However, this treatment is only approved in Switzerland for induction treatment prior to planned ASZT. In contrast, the significantly more expensive KRD regimen is approved as of the second line of therapy.

Treatment of further recurrences

From the third line of therapy (after failure of bortezomib and lenalidomide), the combination of pomalidomide with dexamethasone (Pom/D) is approved in Switzerland [10]. Due to high costs, the approved dosage (4 mg/d) has recently been questioned in favor of an alternating regimen (4 mg every other day), which is potentially significant in terms of health economics [11]. Similar to carfilzomib, questions about optimal dosing in myeloma therapy have been unsatisfactorily resolved in the flurry of product launches.

Another drug approved from the third line onward is the histone deacetylase inhibitor panobinostat in combination with VD. In the PANORAMA-1 study, 768 heavily pretreated patients were treated with panobinostat/VD resp. Placebo/VD treated. Panobinostat is given perorally three days per week at weeks 1 and 2 in a 21-day cycle in addition to VD. There was an improvement in median PFS of nearly four months (12 vs. 8 months) with the same overall survival. The ORR with panobinostat/VD was 60.7%, with a complete response achieved in 11% of patients and a very good partial response in 17%. The most common nonhematologic adverse events included diarrhea (68% vs. 42%), asthenia or fatigue (57% vs. 41%), and peripheral neuropathy (61% vs. 67%). Significant hematologic adverse events were also more common with panobinostat [12].

The first perorally available proteasome inhibitor, ixazomib, is approved in Switzerland in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone from the third line of therapy (or from the second line of therapy if high-risk features are present). The TOURMALINE-MM1 trial compared ixazomib in combination with RD versus placebo/RD. Median PFS was significantly longer in the ixazomib group (20.6 vs. 14.7 months). Hematologic tolerance of both therapies was comparable. Peripheral neuropathy occurred with ixazomib in 27% of patients (vs. 22%) [13]. As a completely peroral therapy, this combination is undoubtedly patient-friendly.

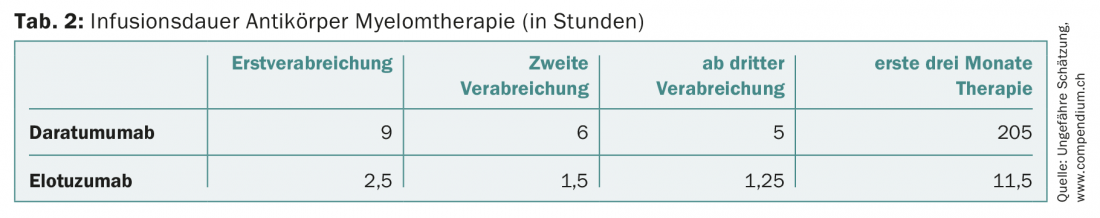

In patients who are refractory to at least one proteasome inhibitor and one immunomodulatory agent, or who have had at least three prior therapies, the CD38 monoclonal antibody daratumumab may also be administered in Switzerland. As monotherapy, daratumumab shows response rates approaching 30% [14]. The antibody, which is to be administered weekly initially, presents a challenge for oncology outpatient clinics with its long infusion duration of nine hours for initial administration (and still at least five hours from third administration) when used more widely. Daratumumab is also newly approved in the second line in combination with dexamethasone and bortezomib or lenalidomide.

Other therapy options

A number of other therapeutic regimens for the treatment of relapsed multiple myeloma can be found in the rapidly growing literature.

In the CASTOR trial, 498 patients with a median of two prior therapies were randomized to daratumumab/VD (Dara/VD) or VD alone. In both treatment arms, VD was stopped after eight cycles each, and daratumumab was allowed to continue until progression. After a median follow-up of 7.4 months, there was a significantly prolonged PFS in the daratumumab group. ORR was significantly higher in the daratumumab arm (82.9% vs. 63.2%) and, in particular, rates of very good partial remission or better were nearly doubled (59.2% vs. 29.1%) [15].

In the POLLUX trial, 569 patients pre-treated with at least one therapy received RD or the combination with daratumumab. After a median follow-up of 13.5 months, the interim analysis showed prolonged PFS in the experimental group (not reached vs. 18.4 months). The ORR was also higher in the daratumumab arm (92.9% vs. 76.4%), as was the rate of complete remissions (43.1% vs. 19.2%) [16]. The main problem with the use of this antibody is infusion reactions and thrombopenias.

There are also data for combinations of Pom/D with a third agent for relapsed myeloma, e.g., in combination with weekly 400 mg peroral cyclophosphamide (PomCyDex) or bortezomib (PVD) [17,18]. Patients with lenalidomide-refractory myeloma were included in both studies. Monotherapy with bendamustine may also be used, particularly in patients with renal insufficiency or who require dialysis [19]. The latter is not approved for this indication in Switzerland.

In two innovative phase II trials, the Swiss Association for Clinical Cancer Research (SAKK) tested the combination of nelfinavir with VD resp. RD investigated. This was based on observations that this HIV drug can restore sensitivity to the two myeloma drugs. The SAKK 39/13 trial achieved a promising ORR of 65% in a very heavily pretreated and frequently bortezomib- and lenalidomide-refractory population [20]. Further SAKK studies with nelfinavir combinations are planned.

Outlook

Data to date on checkpoint inhibitors in multiple myeloma are not promising. In contrast, following FDA approval of CAR T-cell therapy for young patients with relapsed or refractory ALL, this treatment option has become the focus of interest for myeloma patients as well. This is based on data from initial clinical trials in myeloma patients using BCMA-CAR-T cells (“B-cell maturation antigen”) with remission rates around 100% [21–23].

Unprecedented progress has taken place in myeloma therapy. While the average survival time 15 years ago was two to three years, today a good 40% of myeloma patients live ten years or more. However, this improvement has also been reflected in treatment costs (tab. 1) . The latter should be taken into account by the various players in the healthcare system, especially since the new, very expensive drugs will advance to the front line. To stay with the example of daratumumab, this will also increase the organizational, infrastructural and personnel pressure on the oncology outpatient clinics and practices due to the long infusion duration alone (Tab. 2) . The subcutaneous application of this antibody would alleviate the problem [24].

In addition to its effectiveness, treatment for non-curable diseases should primarily improve the quality of life. For the new drugs, these data are still lacking, or quality of life was only a secondary endpoint [25].

In summary, myeloma patients now have a variety of new treatment options. When possible, patients should be included in studies (e.g., SAKK). It would be desirable if protocols increasingly examined treatment sequences and quality of life.

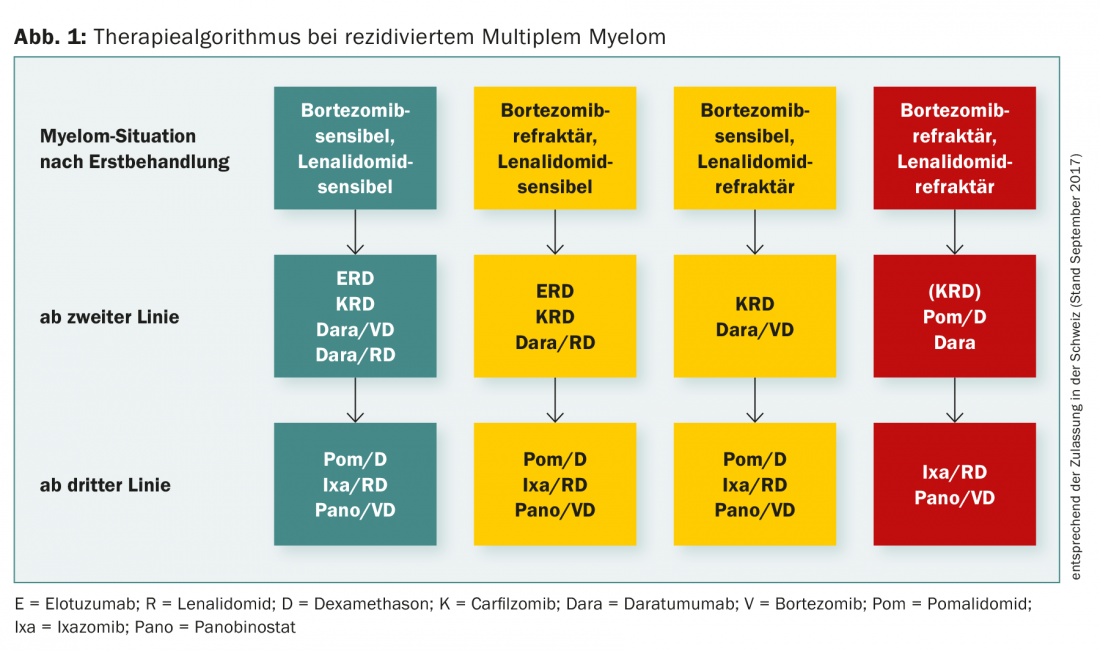

Figure 1 summarizes the treatment algorithm for relapsed multiple myeloma.

Take-Home Messages

- The choice of relapse therapy depends on pretreatment (drug class, response, and tolerance), patient age, performance, and comorbidities, and drug approval.

- Standard in relapse treatment are triple combinations with a proteasome inhibitor and/or an IMID, depending on the pretreatment.

- Antibody therapies occupy an important place in myeloma treatment.

- Myeloma patients should always be treated in protocols (e.g., SAKK) whenever possible.

- CAR T-cell therapy may become a promising option in myeloma.

Literature:

- Weber DM, et al: Lenalidomide plus dexamethasone for relapsed multiple myeloma in North America. N Engl J Med 2007; 357(21): 2133-2142.

- Dimopoulos M, et al: Lenalidomide plus dexamethasone for relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2007; 357(21): 2123-2132.

- Richardson PG, et al: Bortezomib or high-dose dexamethasone for relapsed multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2005; 352(24): 2487-2498.

- Grovdal M, et al: Autologous stem cell transplantation versus novel drugs or conventional chemotherapy for patients with relapsed multiple myeloma after previous ASCT. Bone Marrow Transplant 2015; 50(6): 808-812.

- Giralt S, et al: American Society of Blood and Marrow Transplantation, European Society of Blood and Marrow Transplantation, Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network, and International Myeloma Working Group Consensus Conference on Salvage Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation in Patients with Relapsed Multiple Myeloma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2015; 21(12): 2039-2051.

- Dimopoulos MA, et al: Elotuzumab plus lenalidomide/dexamethasone for relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma: ELOQUENT-2 follow-up and post-hoc analyses on progression-free survival and tumour growth. Br J Haematol 2017; 178(6): 896-905.

- Lonial S, et al: Elotuzumab Therapy for Relapsed or Refractory Multiple Myeloma. N Engl J Med 2015; 373(7): 621-631.

- Stewart AK, et al: Carfilzomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone for relapsed multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2015; 372(2): 142-152.

- Dimopoulos MA, et al: Carfilzomib and dexamethasone versus bortezomib and dexamethasone for patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (ENDEAVOR): a randomised, phase 3, open-label, multicentre study. Lancet Oncol 2016; 17(1): 27-38.

- Dimopoulos MA, et al: Safety and efficacy of pomalidomide plus low-dose dexamethasone in STRATUS (MM-010): a phase 3b study in refractory multiple myeloma. Blood 2016; 128(4): 497-503.

- Zander T, et al: Spotlight on pomalidomide: could less be more? Leukemia 2017; 31(9): 1987-1989.

- San-Miguel JF, et al: Panobinostat plus bortezomib and dexamethasone versus placebo plus bortezomib and dexamethasone in patients with relapsed or relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2014; 15(11): 1195-1206.

- Moreau P, et al: Oral ixazomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2016; 374(17): 1621-1634.

- Usmani SZ, et al: Clinical efficacy of daratumumab monotherapy in patients with heavily pretreated relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. Blood 2016; 128(1): 37-44.

- Palumbo A, et al: Daratumumab, bortezomib, and dexamethasone for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2016; 375(8): 754-766.

- Dimopoulos MA, et al: Daratumumab, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2016; 375(14): 1319-1331.

- Baz RC, et al: Randomized multicenter phase 2 study of pomalidomide, cyclophosphamide, and dexamethasone in relapsed refractory myeloma. Blood 2016; 127(21): 2561-2568.

- Paludo J, et al: Pomalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone for patients with relapsed lenalidomide-refractory multiple myeloma. Blood 2017; 130(10): 1198-1204.

- Hoy SM: Bendamustine: a review of its use in the management of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, rituximab-refractory indolent non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and multiple myeloma. Drugs 2012; 72(14): 1929-1950.

- Driessen C, et al: The HIV Protease Inhibitor Nelfinavir in Combination with Bortezomib and Dexamethasone (NVd) Has Excellent Activity in Patients with Advanced, Proteasome Inhibitor-Refractory Multiple Myeloma: A Multicenter Phase II Trial (SAKK 39/13). Blood 2016; 128: Abstract 487.

- Ali SA, et al: T cells expressing an anti-B-cell maturation antigen chimeric antigen receptor cause remissions of multiple myeloma. Blood 2016; 128(13): 1688-1700.

- Berdeja J, et al: First-in-human multicenter study of bb2121 anti-BCMA CAR T-cell therapy for relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma: Updated results. J Clin Oncol 2017; 35(15 suppl): 3010.

- Fan F, et al: Durable remissions with BCMA specific chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-modified T cells in patients with refractory/relapsed multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol 2017; 35(18 suppl): 3001.

- Usmani S, et al: Open-Label, Multicenter, Dose Escalation Phase 1b Study to Assess the Subcutaneous Delivery of Daratumumab in Patients (pts) with Relapsed or Refractory Multiple Myeloma (PAVO). Blood 2016; 128: Abstract 1149.

- Kvam AK, Waage A: Health-related quality of life in patients with multiple myeloma – does it matter? Haematologica 2015; 100(6): 704-705.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2017; 5(5): 16-20.