The suspected diagnosis of arterial hypertension should be confirmed with ambulatory blood pressure self-monitoring or (better) by 24h blood pressure monitoring. In young patients, negative family history, stage 2 or 3 hypertension, or refractory arterial hypertension, the possibility of a secondary cause of hypertension must be considered. Before starting therapy, it is important to consider the patient’s age, cardiovascular risk factors, any end-organ damage, and concomitant diseases. Selection of antihypertensive therapy is based on co-consideration of concomitant diseases and primarily includes renin-angiotensin inhibitors, calcium antagonists, beta-blockers, and diuretics. Target treatment levels depend on age, health status and concomitant diseases (diabetes).

The latest recommendations of the European Society of Hypertension and Cardiology were published in 2013 and, together with other guidelines (British 2011), serve as the basis of this article [1,2]. Emphasis will be placed on current therapy and therapy goals.

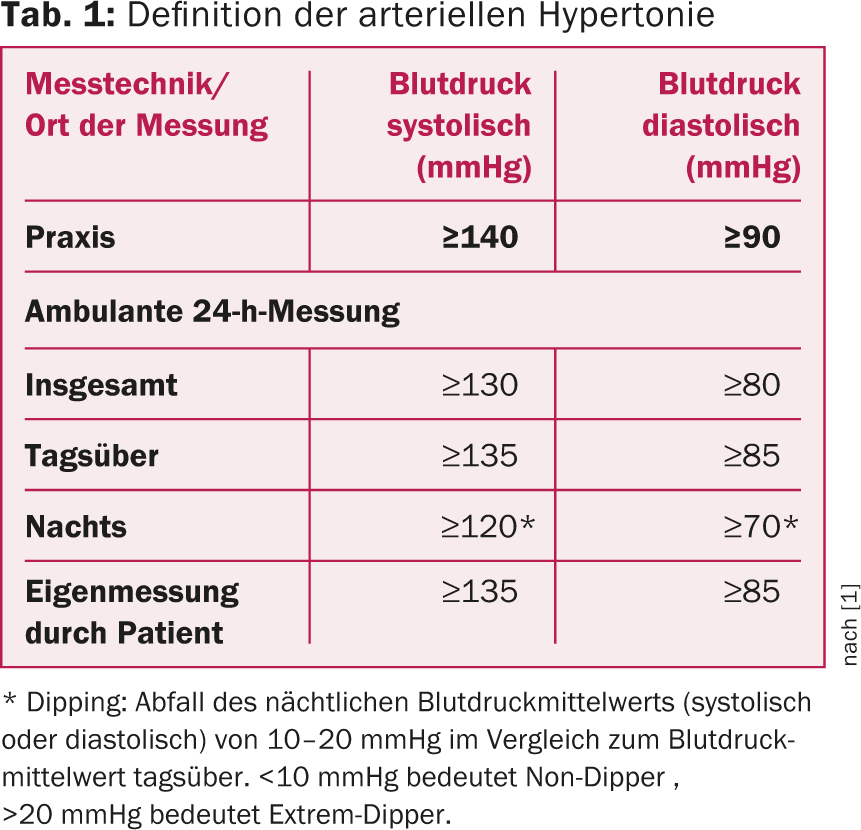

The values that define arterial hypertension vary depending on the measurement technique and measurement site (summarized in table 1 ).

In any patient with elevated blood pressure values, the primary objective is to confirm the suspected diagnosis of arterial hypertension. Whenever possible, blood pressure should be measured by the patient outside the practice or by means of long-term blood pressure measurement (24h blood pressure measurement). Based on this examination, daytime blood pressure progression and nocturnal dipping can be assessed. Likewise, a possible white coat component of arterial hypertension or masked hypertension can be detected.

Further steps before starting treatment

To determine treatment strategy and medication selection, the following questions must be answered once arterial hypertension has been diagnosed:

What is the cause of arterial hypertension? Could it be a secondary cause of hypertension? By far the most common is essential arterial hypertension. Only in 5-10% of cases is there a secondary cause of hypertension. However, in cases of clinical suspicion or abnormal laboratory findings, secondary causes of hypertension should be investigated (Table 2). A secondary cause of hypertension should be considered especially in patients with a negative family history, patients under 30 years of age, grade 2 or 3 hypertension, or treatment-resistant arterial hypertension [3].

How old is the patient, what is the cardiovascular risk, is there end organ damage? Age, cardiovascular risk factors, as well as comorbidities and any end-organ damage are significant for risk stratification and planning of therapeutic regimens. All patients should undergo basic work-up with blood count, creatinine, urea, electrolytes, uric acid, fasting glucose, HbA1c, lipid profile, spot urine with sediment to look for proteinuria or proteinuria with sediment. Microalbuminuria and 12-lead ECG to be performed. Subsequently, the risk calculation and treatment strategy can be taken from Table 3.

What concomitant diseases are known? These influence the treatment strategy, target blood pressure levels, and medication choice and should be evaluated accordingly.

Therapy of arterial hypertension

After answering the above questions, the treatment strategy can be determined according to Table 3. The following treatment options may be considered:

Non-drug treatment options – lifestyle measures: The guidelines emphasize the importance of lifestyle measures. These include regular exercise (30 min. of moderate aerobic exercise at least five days per week), weight loss if overweight (target BMI less than 25 kg/m2) as well as a change in dietary habits with a low-salt diet (5-6 g per day), regular consumption of fruits and vegetables and a low-fat diet, and only moderate alcohol consumption (20-30 g per day for men, 10-20 g per day for women) [1,4]. Due to the often misconception regarding the optimal dietary habits of the patient and their environment, we believe that nutritional counseling is highly recommended. Smoking cessation should also be recommended to patients.

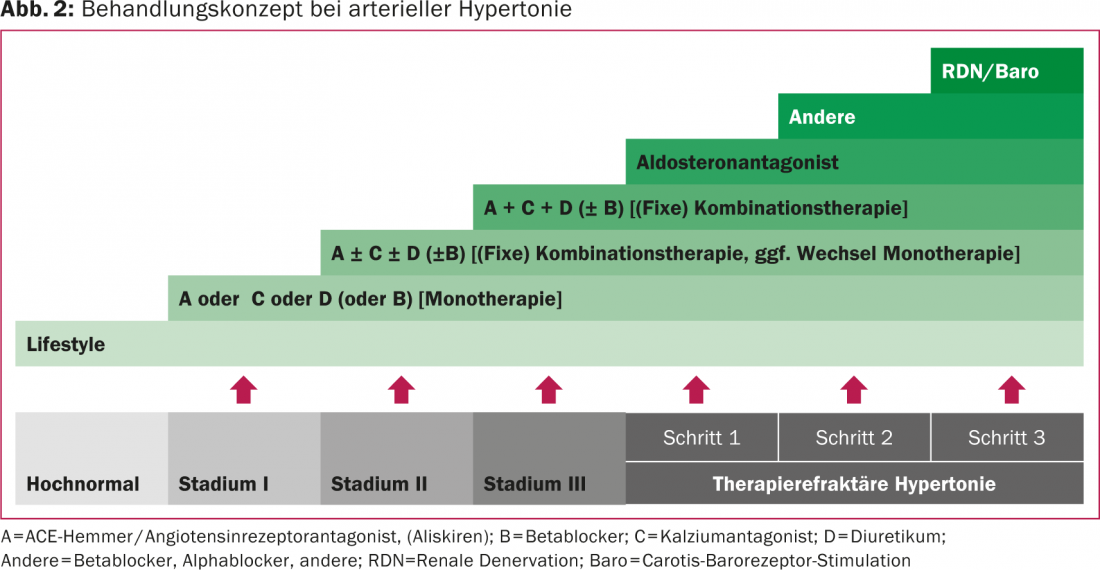

Drug therapy options: In principle, monotherapy can be started in patients with mildly to moderately elevated blood pressure levels and/or low to moderate cardiovascular risk. Current recommendations favor therapy with a renin-angiotensin inhibitor or a calcium antagonist in many cases. If the effect is insufficient, a change to another substance group, an increase in the dose or finally the start of a combination therapy may be considered.

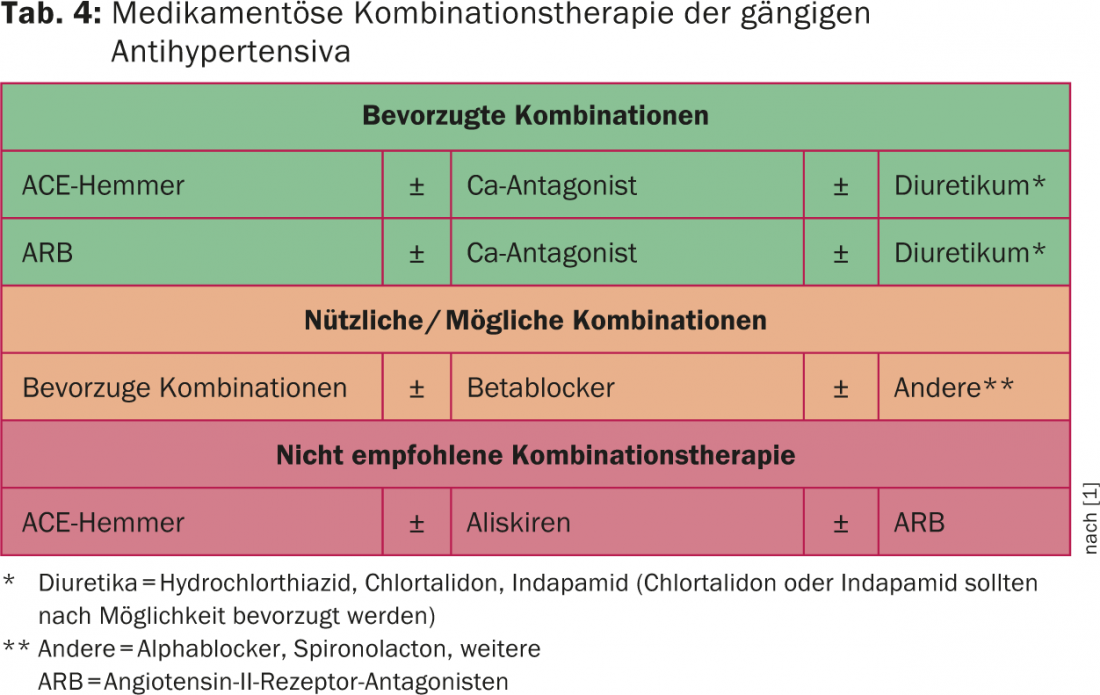

In patients with severely elevated blood pressure levels and/or high to very high cardiovascular risk, (low-dose) combination therapy is primarily recommended. Table 4 provides information on the possible combinations of the current substance groups. The only combination therapy not recommended is concomitant therapy with two inhibitors of the renin-aldosterone system (exception: combination with aldosterone antagonists spironolactone or eplerenone) [5]. Essentially, the selection of medication must also take into account the concomitant diseases (Tab. 5) and the age of the patient.

In our opinion, a good and pragmatic treatment concept is recommended in the British guidelines (Fig. 1) [2].

Invasive therapy options for refractory hypertension.

Treatment-resistant hypertension is defined as blood pressure above 140/90 mmHg despite adequate lifestyle measures and at least three adequately dosed antihypertensives (at least one diuretic) [1]. Certain experts also require the addition of spironolactone or eplerenone. In patients with refractory arterial hypertension, once resistance to therapy is confirmed, invasive therapy options for the treatment of arterial hypertension may be considered at best.

Renal denervation: in recent years, renal denervation seemed to be a valid therapeutic option in patients with refractory arterial hypertension (observational studies Simplicity-HTN1 and 2) [6,7]. However, the results of the first prospective blinded randomized trial (Simplicity-HTN3 trial) have put these findings into perspective. Significant blood pressure reduction was achieved in both the renal denervation group and the patients with sham procedure (angiography) performed. However, the differences between the two groups were not significant [8]. Due to the result, the enthusiasm regarding this therapy option has been strongly relativized. Further studies are needed here. Until then, renal denervation will be reserved for selected patients and patients in trials.

Carotid baroreceptor stimulation: Regarding this therapy option, we refer to the report by Prof. Dr. med. Jürg Schmidli, Bern, in this issue (p. 6 ff).

Renal artery stenting: ren al artery stenosis due to atherosclerosis is relatively common in older hypertensive patients. If renal function has been stable for the past six to twelve months and hypertension can be controlled with medication, no intervention is recommended. Overall, however, controversy persists regarding the benefit of intervention except in patients with bilateral stenosis and recurrent acute cardiac decompensation. Here, invasive treatment is favored [9].

In patients with fibromuscular dysplasia (younger, mostly female patients), the current guidelines recommend percutaneous intervention based on study results (non-controlled trials) [10].

Therapy goals

The treatment concept from mild to refractory arterial hypertension is summarized in Figure 2.

For most hypertensives, the target blood pressure values according to current guidelines are in the range <140/90 mmHg. The only exception is patients with diabetes, where target values of <140/85 mmHg are given. In older patients, slightly higher blood pressure values of 150-160 mmHg systolic may also be acceptable, depending on physical and mental health. Another exception is patients with diabetic or nondiabetic renal insufficiency and proteinuria (protein-creatinine ratio >0.22 g/g [11]). In these patients, systolic blood pressure values <130 mmHg may be considered with close monitoring of renal function.

Treatment of the additional cardiovascular risk factors.

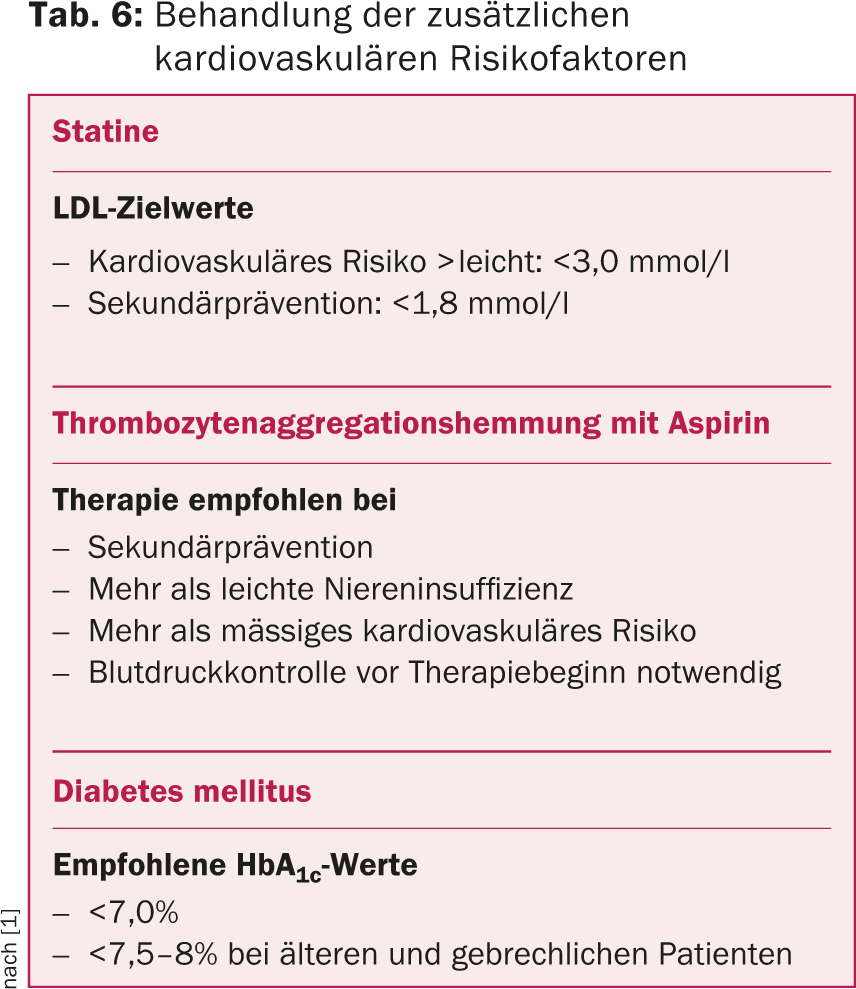

Because arterial hypertension is only one part of the treatment of cardiovascular risk, treatment of the other cardiovascular risk factors is also essential (Table 6).

Literature:

- Mancia G, et al: 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2013; 34(28): 2159-2219.

- Krause T, et al: Management of hypertension: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ 2011; 343: d4891.

- Rimoldi SF, Scherrer U, Messerli FH: Secondary arterial hypertension: when, who, and how to screen? Eur Heart J 2014; 35(19): 1245-1254.

- Dickinson HO, et al: Lifestyle interventions to reduce raised blood pressure: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Hypertens 2006; 24(2): 215-233.

- Mann JF, et al: Renal outcomes with telmisartan, ramipril, or both, in people at high vascular risk (the ONTARGET study): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, controlled trial. Lancet 2008; 372(9638): 547-553.

- Krum H, et al: Catheter-based renal sympathetic denervation for resistant hypertension: a multicentre safety and proof-of-principle cohort study. Lancet 2009; 373(9671): 1275-1281.

- Esler MD, et al: Renal sympathetic denervation in patients with treatment-resistant hypertension (The Symplicity HTN-2 Trial): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2010; 376(9756): 1903-1909.

- Bhatt DL, et al: A controlled trial of renal denervation for resistant hypertension. N Engl J Med 2014; 370(15): 1393-1401.

- Gray BH, et al: Clinical benefit of renal artery angioplasty with stenting for the control of recurrent and refractory congestive heart failure. Vasc Med 2002; 7(4): 275-279.

- Safian RD, Textor SC: Renal-artery stenosis. N Engl J Med 2001; 344(6): 431-442.

- Appel LJ, et al: Intensive blood-pressure control in hypertensive chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 2010; 363(10): 918-929.

CARDIOVASC 2014; 13(6): 12-17