Smoking harms health, every child knows that. Nevertheless, the cigarette seems to exert a special fascination on many people – and has done so for centuries. Many smoking cessation measures have already been launched, but without success. Smoking rates remain almost constant. What is it that makes smoking sticks so attractive that people reach for them against their better judgment and put their health at risk? And above all: what exactly makes smoking so harmful? A search for traces…

It was about 50 years ago that you were one of the “cool kids” if you could call a pack of gum or chocolate cigarettes your own. At that time, the health risk from smoking was not considered so high. Even on television, it was almost good manners to light up a cigarette. It was only later that medical knowledge about possible health consequences prevailed. Meanwhile, reaching for tobacco in public buildings is prohibited. In addition, a drastic image with a powerful slogan is emblazoned on each box as a deterrent. And what does man do? He will not be swayed. Tobacco use remains one of the biggest public health problems. Since 2011, the number of smokers in Switzerland has not changed – more than 27% of all residents over 15 years reach for cigarette and Co. In the youngest group of 15-24 years, it is even almost 32% [1]. While the classic smoker used to be found predominantly in the world of successful men, the picture has changed over time. Meanwhile, the prototype is young, socially disadvantaged and financially poor. In addition, women are also increasingly turning to cigarettes [2].

What makes smoking so fascinating?

The tobacco plant originates from the South American continent, where it was used in spiritual rituals by Mayan priests as early as 600-500 BC. The leaves were lit and the smoke inhaled. It was not until the end of the 15th century that the plant found its way to Europe through Spanish conquerors. In Switzerland, it was the soldiers returning home from the Thirty Years’ War who brought smoking to the country in the second half of the 17th century. Until the 19th century, tobacco was mainly chewed, snuffed or smoked in pipes. The first cigarette machine was invented in 1867. Although smoking was banned in all countries by means of sometimes drastic penalties, it could no longer be stopped. As a result, rulers soon adopted a different strategy: they promoted and protected tobacco cultivation and then subjected the products to a targeted tax. Nevertheless, cigarettes remained a comparatively inexpensive stimulant that was affordable for the masses and increasingly accepted by society. After the First World War, the first large tobacco companies emerged in America and the machine production of cigarettes became established [3,4].

There are many reasons to start smoking. Often it is curiosity, the forbidden or even the circle of friends, before which one does not want to give oneself a nerve. Over time, the motivation changes – also gender-specific. While stimulation is the main focus for men, smoking usually has a specific function for women. For example, anger and aggression want to be blocked or sadness and loneliness want to be relieved [2]. The individual ritual associated with smoking, as well as the effect of nicotine, are the two main reasons to reach for the glow stick, even though the harmfulness associated with it is widely well known. A study also claims to have found that some people are born with an increased risk of addiction because the brain responds more clearly to nicotine [5].

Not only heart and lungs suffer

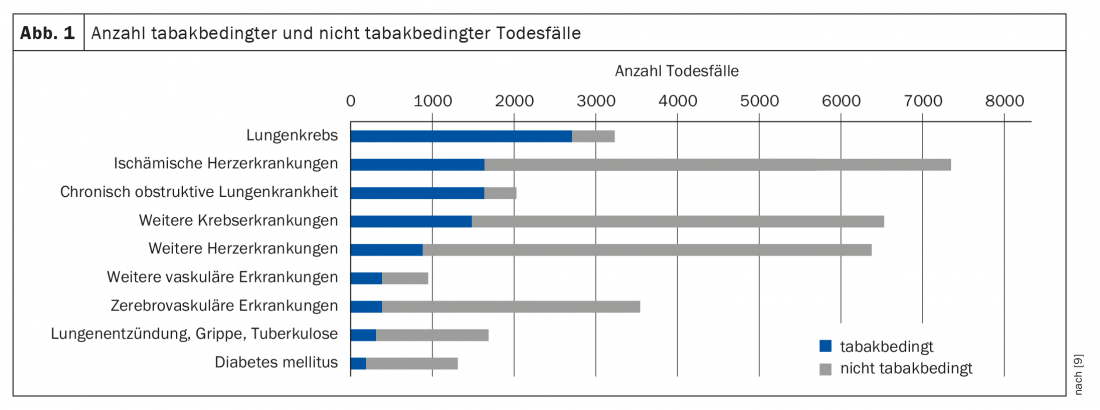

The burden of disease from cigarette use is very high and a variety of different diseases in almost every organ can occur [6]. Smoking is the most important preventable risk factor for chronic noncommunicable diseases [7]. In Switzerland, about 9500 people die each year as a result of smoking, which corresponds to 14.1% of all deaths. Smoking continues to cause the most preventable deaths in Switzerland [8]. Cancers account for the largest proportion of smoker-related deaths at 44% [9]. 90% of all lung cancer cases can be attributed to tobacco use. Among these, malignancies account for the largest proportion of tobacco-related deaths (44%), followed by cardiovascular disease (35%) and respiratory disease (20%) [9]. (Fig. 1). The amount of tobacco consumption is not as decisive as previously assumed. Just one cigarette a day can increase the risk of coronary heart disease and stroke by a factor of 1.48 and 1.25, respectively. increase significantly. Thus, the risk is only about 50% lower than for people who consume 20 cigarettes per day [10]. Psychological aspects also play a role. Furthermore, research shows that smokers are two to four times more likely to suffer from anxiety disorders or depression compared to non-smokers [11]. The important question here is whether smoking makes people mentally ill, or whether people with mental health problems are more likely to turn to cigarettes. As far as we know so far, both are possible [12]. However, the fact is – smoking costs valuable life time: on average smokers lose 14 years of their life – half do not even reach the age of 70 [13].

Tobacco – the great danger!?

Nowadays, when we talk about tobacco, we no longer mean the leaves of the tobacco plant. Over time, hundreds of additives have been added to raw tobacco. Thus, tobacco smoke is a complex mixture of over 7000 chemicals. The problem arises from the combustion process [14–16]. In the high temperatures of the glow zone of 600 to 900°C, both the tobacco and the additives evaporate, sublimate or burn. This produces the typical composition of water, nicotine and TAR for tobacco smoke. TAR is the abbreviation for “Total Aerosol Residue” and is also often translated as “tar”. To prevent misunderstandings, the term “tar” has now been abolished in professional circles and replaced by the abbreviation NFDPM [Nicotine Free Dried Particle Matter). Various scientific and regulatory bodies such as FDA, IARC or Health Canada, have confirmed the presence of more than 100 harmful and potentially harmful constituents in tobacco smoke as of today. These include carbon monoxide, formaldehyde, acetaldehyde, acrolein, benzenes, benzopyrenes and butanones [17].

Addictive substance nicotine

Nicotine, which is also present in tobacco smoke, is an alkaloid naturally occurring in the tobacco plant and also in other nightshade plants with effects on the autonomic nervous system. It has a stimulatory effect on nicotinic acetylcholine receptors located in parasympathetic and sympathetic ganglia, adrenal medulla, central nervous system, and motor end plates. The parasympathetic nervous system is activated, the sympathetic nerves are inhibited and the release of adrenaline, dopamine and serotonin is promoted. Combined with a high rate of onset of tobacco smoking, this quickly leads to dependence. Nicotine is only toxic in very high doses and then leads to nausea and vomiting. However, it is not on the World Health Organization’s list of carcinogenic substances [18].

As far as the health-damaging aspect of nicotine is concerned, the data situation is very contradictory [19–23]. However, it appears that the consumption of pure nicotine at comparable doses poses fewer risks compared with cigarette smoking, with its assured health consequences. In contrast, attempts to reduce nicotine use through nicotine-free or low-nicotine cigarettes and thereby strengthen the body’s health have failed. This is because, as more cigarettes were consumed in a compensatory manner, significantly more toxic substances resulting from the combustion process were ingested. This is where the new alternative products to smoking such as vaporizers, heaters or e-cigarettes come in. The ingredients are no longer burned, but only heated. In this way, the substances in the aerosol can be avoided or at least massively reduced [17].

The crux of combustion

Tobacco consumption has exerted a great attraction on people for centuries. The focus is not necessarily on addiction alone, but also on the rituals associated with smoking. The harmful effect on health usually develops as a result of the combustion process of the organic material.

Literature:

- www.bag.admin.ch/bag/de/home/zahlen-und-statistiken/zahlen-fakten-zu-sucht/zahlen-fakten-zu-tabak.html (last accessed on 04.08.2020)

- www.welt.de/gesundheit/psychologie/article3144940/Frauen-rauchen-aus-anderen-Gruenden-als-Maenner.html (last accessed on 04.08.2020)

- www.apotheken-raucherberatung.ch/de/startseite/facts-zum-rauchen/geschichte.html (last accessed on 04.08.2020)

- www.powercigs.net/geschichte-des-rauchens.html (last accessed on 04.08.2020)

- Gehricke JG, Loughlin SE, Whalen CK, et al: Smoking to Self-Medicate Attentional and Emotional Dysfunctions. Nicotine & Tobacco Research 2007; 9:523-536.

- www.bundesaerztekammer.de/fileadmin/user_upload/downloads/TabakEinhalt2007.pdf (last accessed on 04.08.2020)

- www.dkfz.de/de/tabakkontrolle/Gesundheitliche_Folgen_des_Rauchens.html (last accessed 04.08.2020)

- www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home/aktuell/neue-veroeffentlichungen.assetdetail.350100.html (last accessed 10/13/2020)

- Mattli R, et al: The burden of disease of tobacco use in Switzerland: estimate for 2015 and projection to 2050; final report; ZHAW. Available at: https://zahlen-fakten.suchtschweiz.ch/docs/library/mattli_ort8gw7xd8ig.pdf

- Hackshaw A, Morris JK, Boniface S, et al: Low cigarette consumption and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke: meta-analysis of 141 cohort studies in 55 study reports. BMJ 2018; 360:j5855.

- www.bundesaerztekammer.de/aerzte/versorgung/suchtmedizin/tabak/gesundheitliche-auswirkungen/ (last accessed on 04.08.2020)

- www.rauch-frei.info/informier-dich/news/detailseite/raucherinnen-und-raucher-haeufiger-seelisch-krank.html (last accessed 10/13/2020)

- www.bag.admin.ch/bag/de/home/gesund-leben/sucht-und-gesundheit/tabak.html (last accessed 10/13/2020)

- www.pharmazeutische-zeitung.de/ausgabe-302015/die-seele-raucht-mit/ (last accessed on 04.08.2020)

- www.health.govt.nz/publication/chemical-constituents-cigarettes-and-cigarette-smoke-priorities-harm-reduction (last accessed on 05.08.2020)

- Schmeltz I, Schlotzhauer WS: Benzo[a]pyrene, Phenols and other products from pyrolysis of the cigarette additie, (d,l)-menthol. Nature 1968; 219: 370-371.

- Margham J, McAdam K, Forster M, et al: Chemical Composition of Aerosol from an E-Cigarette: A Quantitative Comparison with Cigarette Smoke. Chem Res Toxicol. 2016; 29(10): 1662-1678.

- https://monographs.iarc.fr/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/ClassificationsAlphaOrder.pdf. (last accessed on 05.08.2020)

- Ahmad S, Zafar I, Mariappan N, et al: Acute pulmonary effects of aerosolized nicotine. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2019; 316(1): 94-104.

- Haussmann HJ, Fariss MW: Comprehensive review of epidemiological and animal studies on the potential carcinogenic effects of nicotine per se. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2016; 46(8): 701-734.

- Lee HW, Park SH, Weng MW, et al: E-cigarette smoke damages DNA and reduces repair activity in mouse lung, heart, and bladder as well as in human lung and bladder cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2018; 115(7): E1560-E9.

- Phillips B, Esposito M, Verbeeck J, et al: Toxicity of aerosols of nicotine and pyruvic acid (separate and combined) in Sprague-Dawley rats in a 28-day OECD 412 inhalation study and assessment of systems toxicology. Inhal Toxicol. 2015; 27(9): 405-431.

- Waldum HL, Nilsen OG, Nilsen T, et al: Long-term effects of inhaled nicotine. Life Sci. 1996; 58(16): 1339-1346.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2020; 15(10): 26-27