The incidence of anemia increases with age and cannot be considered a normal physiological sign of aging. In persons over 65 years of age, the prevalence of anemia ranges from 10 to 15%, and in the elderly over 80 years of age, the prevalence ranges from 20 to 25%. In nursing homes and hospitals, this prevalence is significantly higher at 40%. Compared to younger adults, anemia in old age is not only more common, but also leads to many more and more severe consequences. This article provides an overview for clarification and treatment.

Even mild anemia can have relevant effects in persons over 70 years of age, threatening the patient’s independence through loss of function. Elderly patients with comparable anemia to young patients have more symptoms, poorer quality of life, and a higher risk of morbidity and mortality. The reduced performance and muscle strength leads them to be more frail, fall more often and suffer more from depression. Because of the increased risk of falls, there is also an increased risk of fracture, especially in the case of reduced bone density and muscle mass. Consequently, anemia can contribute to an older person’s loss of independence. These patients are therefore more often and more dependent on support in daily life. The problem of anemia in old age thus affects not only the patient himself, but also his social environment with corresponding relevance for health policy.

Clarification of anemia in old age: What needs to be clarified and why?

In primary care practice, it is a matter of determining, in the patient with anemia, what goal should be achieved. This is crucial for the type of clarification and the choice of treatment. The goal to be achieved is not determined purely by the patient’s chronological age, but also by his biological condition, functional autonomy, social embeddedness, and expectations (and the expectations of his family).

A minimal basic work-up must allow the identification of forms of anemia that are easy to treat. Anemias of older patients are basically due to the same mechanisms as in younger adults. However, the distribution of causes may differ. In simple terms, the causes of anemia in old age can be divided into three groups:

- One third of patients have deficiency anemia (iron, B12, folic acid)

- A second third of patients have anemia in chronic inflammation and/or renal insufficiency

- In the last third of patients, the cause remains unknown.

This last group includes forms of anemia that are not detected by the basic workup, such as anemia in myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) or another hematologic neoplasm, hemolytic anemia, hemorrhage, or drug-toxic causes. However, despite complete intensive investigations, some of the anemias remain unexplained. There is now evidence that low-grade inflammation plays a pathophysiological role in the development of frailty and anemia in old age.

Practically, about half of the patients in old age have anemia, which can be treated with simple means: deficiency anemia (iron, vitamin B12 and folic acid deficiency), renal insufficiency, chronic inflammatory diseases (e.g. tumor) or chronic bleeding. In addition, poor nutrition, polymedication and excessive alcohol consumption must also be considered. More often than in young adults, anemia is multifactorial, which complicates its workup and treatment. A typical example is the patient with a rheumatic disease who simultaneously has an iron deficiency due to chronic bleeding while regularly taking non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and reduced iron absorption. Furthermore, there is still a moderately severe renal insufficiency.

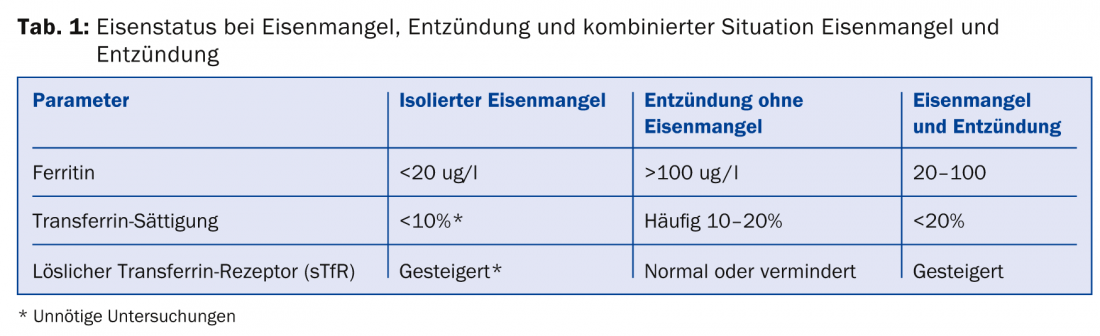

In the elderly, the results of anemia workup are often atypical and treatment is usually more complex than in the younger person. In a young adult, iron deficiency can usually be confirmed with determination of ferritin alone. A low ferritin is then evidence of iron deficiency. In advanced age, iron deficiency is often associated with inflammation. In this case, even a normal or elevated ferritin does not rule out iron deficiency. A complete iron status is then helpful (Table 1).

Thus, the minimum basic workup includes a CBC, reticulocytes, microscopic differentiation, iron status (ferritin, transferrin saturation, and soluble transferrin receptor if present), vitamin B12 and folic acid, creatinine, CRP, liver values, and Coombs test. Depending on the situation, it must be decided whether and which further clarifications must be carried out and when the specialist, i.e. the hematologist, should be consulted.

Treatment of anemia in old age

“Function determines the need for treatment, disease determines the therapeutic options” [1]. In old age, it is less a matter of curing the underlying disease than of maintaining the patient’s quality of life and independence in everyday life. Effective treatment of anemia can also prevent or reduce typical geriatric complications such as falls, depression, cognitive impairment, or forgetfulness and restore functional autonomy.

The treatment of anemia depends on its cause and the goal to be achieved. The social context can have a significant influence on the goals of therapy and the decision on appropriate treatment: for example, a patient who still lives alone in his or her own home and can manage shopping, household chores, and other daily functions independently may require greater support to achieve certain goals than someone who has been bedridden in a home for some time and is not even aware of anemia-related limitations.

Simple therapeutic approaches for the treatment of anemia in geriatric patients include deficiency replacement, erythropoietin treatment in renal failure and in tumor anemia, and red cell transfusions as needed.

Red cell concentrates: in patients of advanced age, anemia may pose a cardiovascular risk. Transfusions of red blood cell concentrates are the only way to correct anemia immediately. A precise hemoglobin threshold for transfusion administration has not been clearly defined. The decision to transfuse is based less on a hemoglobin value than on the patient’s condition, cardiovascular risk, and speed of onset of anemia. In adults with bleeding from the gastrointestinal tract, the transfusion trigger is 70 g/l with target values of 70-90 hemoglobin [2]. However, this hemoglobin limit may be higher in elderly patients. Patients with chronic anemia, such as those with MDS, often require two red cell concentrates every two weeks to maintain a hemoglobin between 80 and 100 g/L.

Iron treatment: iron treatment is more complex in patients of advanced age. In adolescent adults with simple iron deficiency, oral iron supplementation is quite an appropriate choice of substitution. Intravenous iron substitution may be instituted in cases of noncompliance or intolerance. In patients of advanced age, it is quite reasonable to start primarily with intravenous treatment. The following reasons militate against effective oral treatment: compliance is often uncertain in elderly patients because of polymedication and forgetfulness; impaired absorption of iron is also often present, especially with achlorhydria, use of proton pump inhibitors, and often associated inflammation (inhibits enteral absorption).

Erythropoietin substitution: erythropoietin substitution (EPO) is an efficient way to correct renal anemia. Renal anemia is usually moderate, normocytic, normochromic, and hyporegenerative, has inadequately low EPO levels, and persists after correction of other causes of anemia. Treatment with EPO is efficient and safe if the necessary precautions are taken into account. Too rapid an increase in hemoglobin (increase of more than 10 g/l within two weeks) and too high a target hemoglobin are associated with increased cardiovascular mortality and thromboembolic events. During EPO treatment, the hemoglobin level should not exceed 120 g/l. For optimal efficiency of EPO treatment, sufficient iron must be available. Otherwise, a functional iron deficiency occurs: the iron is present in the organism, but is not bioavailable quickly enough. Regular intravenous iron supplementation may prevent functional iron deficiency during EPO treatment, resulting in a desirable increase in hemoglobin.

Anti-neoplastic substances

Patients should not be automatically excluded from specific treatment on the basis of age. Even 70- or 80-year-old patients may benefit from treatment with new anti-neoplastic agents if there are no significant comorbidities (cardiac, pulmonary, hepatic, or renal) and the patient has good functional autonomy. Thus, it may well be worthwhile to clarify anemia in the context of MDS, chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) or myeloma and to treat it accordingly. However, management, workup, and treatment should be done in collaboration with a hematologist.

Summary

Anemia in the elderly implies a reduction in quality of life, a loss of functional autonomy, and an increased risk of morbidity and mortality. First of all, easily treatable causes should be clarified in the family doctor’s office and treated accordingly. However, in some circumstances, patients of advanced age may also benefit from treatment for hematologic disease. The appropriate clarifications and treatments should take place in collaboration with a hematologist.

Prof. Dr. med. André Tichelli

Literature:

- Stähelin H: Special features of geriatrics. In: Zöllner N (ed.) Internal Medicine. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg New York Tokyo 1991; 657-668.

- Carson JL, et al: Red blood cell transfusion: a clinical practice guideline from the AABB. Ann Intern Med 2012; 157: 49-58.

CONCLUSION FOR PRACTICE

- The problem of anemia in old age affects not only the patient himself, but also his social environment.

- In family practice, one must determine what goal is to be achieved. This is crucial for the type of clarification and the choice of treatment.

- Anemia is more often multifactorial than in young adults, which complicates workup and therapy.

- The minimal basic workup includes: CBC, reticulocytes, microscopic differentiation, iron status (ferritin, transferrin saturation and soluble transferrin receptor, if applicable), vitamin B12 and folic acid, creatinine, CRP, liver values and Coombs test.

- Deficiency replacement, erythropoietin treatment in renal insufficiency and in tumor anemia, and red blood cell transfusions when needed are simple therapeutic approaches to treat anemia in geriatric patients.

- In some circumstances, older patients may also benefit from treatment of hematologic disease.

A RETENIR

- Le problème de l’anémie de la personne âgée concerne non seulement le patient lui-même mais également son environnement social.

- Dans la pratique de la médecine générale, il convient de préciser quel est l’objectif à atteindre. Cela est décisif en ce qui concerne le type d’évaluation et le choix du traitement.

- L’anémie est plus fréquemment multifactorielle que chez les adultes jeunes, ce qui complique l’évaluation et le traitement.

- L’évaluation minimale de base nécessite: formule sanguine complète, réticulocytes, différenciation microscopique, bilan martial (ferritine, saturation de la transferrine et, le cas échéant, le récepteur soluble de la transferrine), vitamine B12 et acide folique, créatinine, CRP, paramètres hépatiques et test de Coombs.

- La compensation d’un déficit, le traitement par l’érythropoïétine dans l’insuffisance rénale et dans l’anémie tumorale et les transfusions de globules rouges si nécessaire, sont des options thérapeutiques simples pour le traitement d’une anémie chez les patients gériatriques.

- Le cas échéant, les patients âgés peuvent également profiter du traitement d’une maladie hématologique.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2014; 9(11): 42-46