The creation of an artificial bowel outlet is often the “emergency exit” from a complex surgical situation. For the patient, this represents a serious intervention with radical changes in body image and considerable psychological stress. A comprehensive contribution to practical knowledge in the care of stoma patients.

The creation of an artificial bowel outlet is often the “emergency exit” from a complex surgical situation. This installation may be necessary for a limited period of time for safety reasons, but may also be necessary for life. Reasons for the creation of an artificial bowel outlet can be found in the underlying disease, in the surgery performed, in the patient’s condition or in his co-morbidities.

The Greek word “stoma” means mouth or opening. The medical meaning is a surgical opening in the abdominal wall to expel small bowel secretions or stool from a section of the intestine. The creation of stomas is probably the oldest surgical procedure and dates back to ancient times. The term “anus praeter” means an artificial bowel outlet and says nothing about the location and type of stoma.

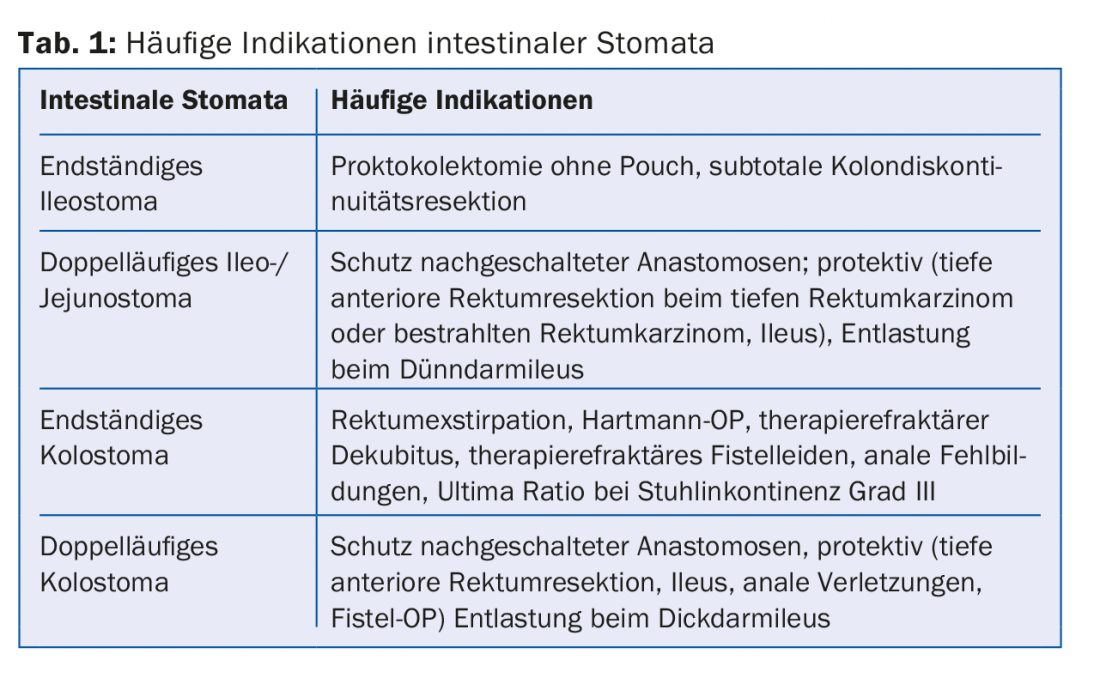

In connection with the anatomical location, a distinction is made between an enterostoma (bowel diversion of the small intestine) and a colostoma (bowel diversion of the large intestine) (Fig. 1) . An ileostoma is the bowel diversion of the end of the small intestine (ileum), a descendostoma the bowel diversion of the descending colon (descending colon), a sigmoidostoma the bowel diversion of the sigma. A distinction is made between an artificial bowel outlet that is created temporarily (passager) and an artificial bowel outlet that must remain in place for life (definitiv).

Furthermore, a distinction is made between a single- and a double-barreled artificial anus (Fig. 2). The definition here is whether one (supplying) or two (supplying and discharging) bowel legs are discharged from the abdominal wall. A split stoma is the separate evacuation of the inflowing and outflowing bowel at different locations in the abdomen. In principle, it can be summarized that double-barrelled stomas are usually created for temporary bowel outlets, whereas lifelong stomas are usually single-barrelled.

The purpose of a temporary bowel outlet is to spare a downstream section of bowel, i.e., stool is temporarily diverted to protect an anastomosis, for example. After the downstream bowel segment has healed, the stoma can be relocated and reconnected to the bowel system in what is usually a minor surgery. The indications for stoma creation concern elective procedures as well as emergency interventions and usually include the questions whether intestinal anastomosis is technically possible or the risk of anastomosing intestinal ends is too high. Elective indications are given in congenital malformations, in severe fecal incontinence, after rectal extirpation or in destructive anal fistula disease. Emergency indications include ileus surgery, bowel perforations, anastomotic insufficiencies, and anorectal impalement injuries (Table 1) [1].

Criteria for optimal stoma position include flat, irritation-free skin. There should be no skin folds, scars or bony prominences located near the stoma. The stoma should be placed below or above the waistband and within the rectus sheath. It should be easily visible by the patient and self-supplied. Optimal placement is below the umbilical level and outside the laparotomy wound.

Stomaphysiology and dysfunction after loss of individual bowel segments

Physiological functions of the small and large intestine are the regulation of water and electrolyte balance as well as the absorption of nutrients, vitamins and trace elements.

Six liters of digestive juices are reabsorbed daily proximal to the ileocecal valve. The reabsorption rate in the colon is approximately 800 ml. The ileocecal valve prevents the backflow of colon contents into the small intestine. If the ileocecal valve is removed, there is increased bacterial colonization of the small intestine with colon bacteria. This leads to an additional reduction of bile acids due to bacterial breakdown and thus to a disturbance of fat digestion. Bacterial binding of the vitamin B12 complex poses a risk of vitamin B12 deficiency.

The more oral the stoma site, the more likely the stools may be mushy to liquid in consistency. In this case, adequate fluid and electrolyte substitution must be ensured. A colostomy is usually associated with adequate thickening function and causes minor metabolic problems. More often, patients suffer from coprostasis. The frequent ileostomy is usually well tolerated. Stools are thin or mushy due to increased water content or decreased reabsorption. The increased losses are compensated for by increased reabsorption by the kidney with reduced urine volume (approx. 1 l). Increased intravascular fluid intake can maintain normal urine volume. This compensation process requires increased amounts of drinking and takes 1-4 weeks.

Disconnected segments of the small intestine can result in high electrolyte and fluid losses that exceed the kidney’s ability to compensate. Consequences include metabolic acidosis with bicarbonate and electrolyte loss, a decrease in glomerular filtration rate, tubular dysfunction, and the development of secondary hyperaldosteronism. Serious electrolyte disturbances and acute renal failure should be noted.

If the jejunum is eliminated by a stoma or if extensive ileum resection is performed, irreversible loss of bile acid reabsorption (chologenic diarrhea) occurs in addition to diarrhea. Likewise, insufficient absorption of fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K) may occur and cause vitamin deficiency symptoms.

A residual jejunum length of >100 cm is necessary to ensure sufficient oral compensation of daily stoma losses via the remaining resorptive capacity.

Magnesium losses are common in jejunostomy carriers and become symptomatic with fatigue, depression, and muscle weakness.

Stoma complications

The cumulative complication rate after stoma placement is at least 50% [2]. In addition to pain, leakage or frequent detachment of the ostomy appliance can occur, which can severely limit a normal life. Work absenteeism, need for care, and increased material consumption can also cause economic problems.

Parastomal skin complications: A very large number of stoma carriers experience peristomal skin problems [3]. Changes in the skin surrounding the stoma should be treated early and promptly with the primary care physician and the stoma therapist. Infection-related skin complications include folliculitis, mycosis, and abscess or erysipelas. Common non-infection-related skin complications include toxic contact dermatitis and allergic contact dermatitis.

Early complications after stoma creation: Postoperatively, stomas must be assessed regularly to detect postoperative stoma edema, stoma necrosis, or bleeding. Mucosal avulsion or retraction may occur at the stoma skin margins. In many cases, this requires extensive outpatient wound care.

Surgical complications include pain in the stoma area, mucosal changes, more severe bleeding from the stoma, defecation problems, stool retention, and cramping abdominal pain, which should always be evaluated by the primary care physician. Common causes include parastomal hernia, parastomal prolapse, stomal stenosis, or stoma retraction.

Parastomal hernia is a fairly common occurrence [4]. The incidence is reported to be 48% for the terminal colostomy [5]. The cause is the expulsion of the bowel through a gap in the rectus muscles, which can expand to form a hernial orifice due to bowel activity. Risk factors for the occurrence of parastomal hernias include obesity, advanced age, cortisone therapy, chronic lung disease, and malnutrition [6]. Parastomal hernia usually requires surgical treatment. Many surgical clinics already use a preventive mesh fitting when a definitive colostomy is created [7].

Supply systems

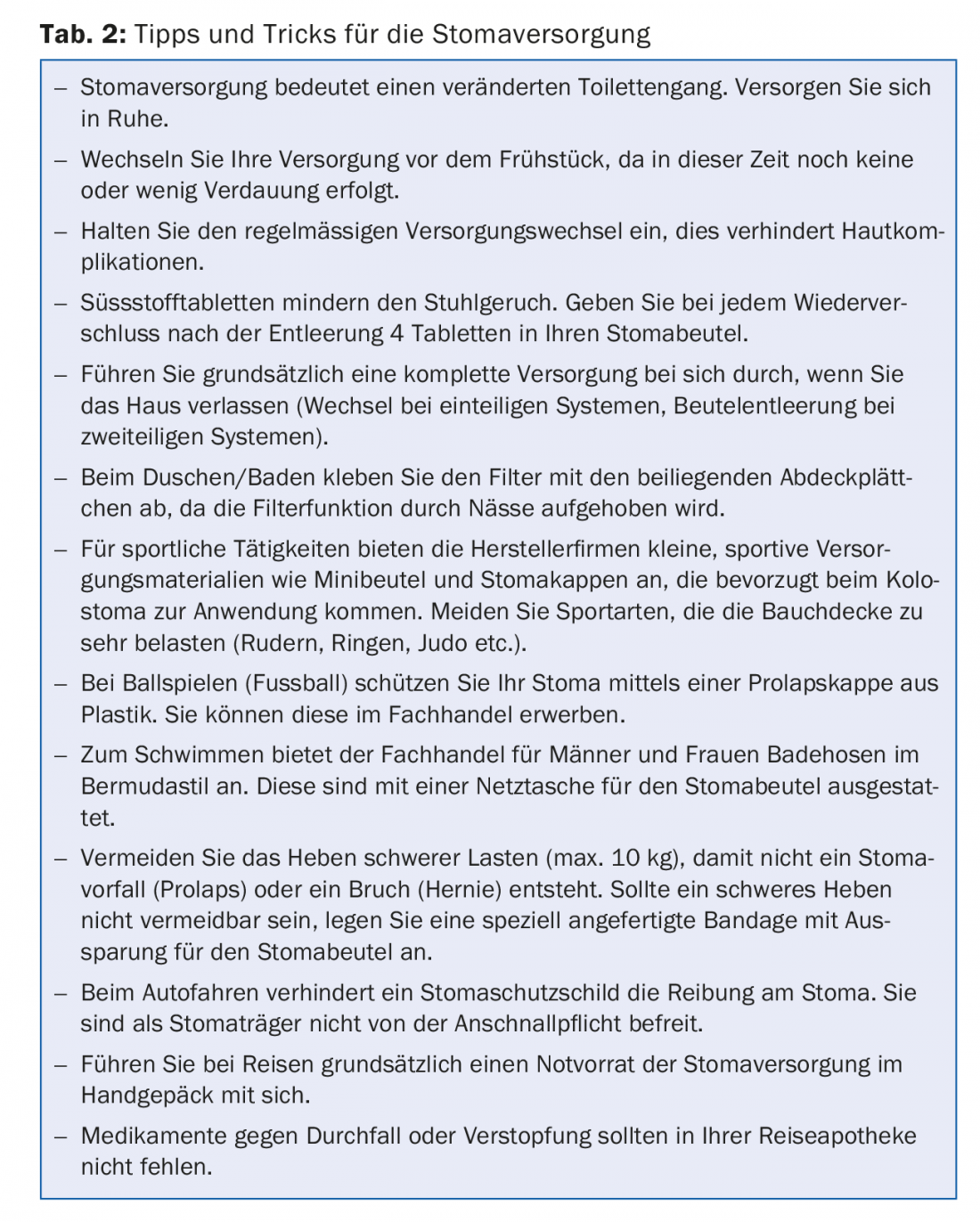

The decision which supply system to choose depends on several factors: the skin condition, the anatomical position, the shape and size of the stoma, the clothing habits or any disabilities (impaired vision, arthritis in the fingers, etc.). Basically, all supply systems are waterproof. This allows a stoma wearer to shower, bathe and swim. Since flatulence is discharged through the stoma, integrated filters prevent the stoma bag from inflating. A patient should learn how to handle and care for a stoma during the hospital stay (Tab. 2).

In the case of a definitive artificial colon outlet (colostomy), a morning colonic irrigation is a good prerequisite for bowel emptying. This restoration of continence for 24-48 hours allows patients a higher quality of life through minimal care and means more independence in everyday life.

Artificial bowel outlet and psyche

Everyone reacts differently to a body image change and has their own personal way of dealing with it. The stoma is one of the hidden body image changes. A stoma user’s own well-being depends on his or her attitude toward the stoma. With the acceptance and acceptance of the stoma, it is easier to cope with everyday life. Patients gain routine through regular supply changes, which gives them a sense of security without anxiety. Your self-esteem and confidence increases and this improves your quality of life.

Patients should take time to come to terms with the new situation. They should be able to talk openly about their feelings and thoughts with their partner, family members, people they trust, and their primary care physician or ostomy therapist. Assistance and good advice is also provided by the ILCO self-help group.

The optimum situation is when a stoma carrier can resume professional, sporting and even intimate contacts after a period of adaptation.

Dietary recommendations for artificial bowel outlet

The artificial bowel outlet does not require a special diet. An easily digestible, varied and vitamin-rich mixed diet and a restriction of fat intake are recommended. Fresh, little-treated food should be consumed instead of cured and smoked food.

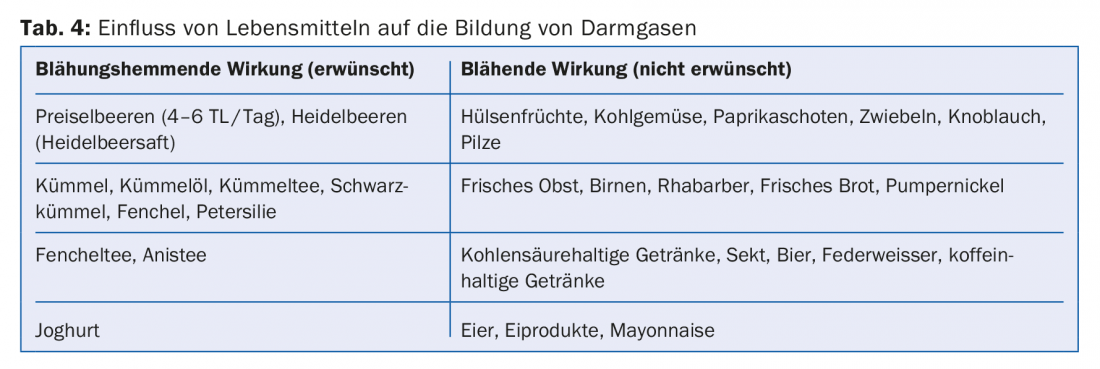

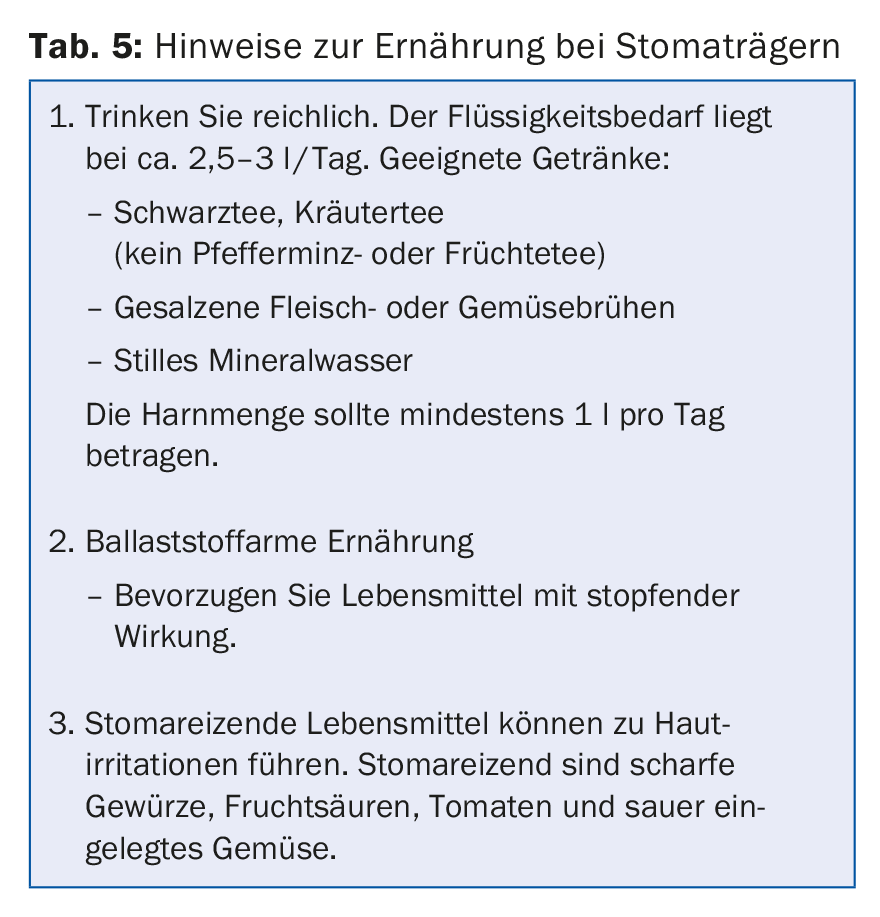

Avoid flatulent vegetables, mushrooms and legumes. Cranberries have a good deflating effect, besides they have an anti-odor effect on the stool odor. Dietary fiber stimulates intestinal activity, binds harmful substances and promotes intestinal flora. Finely ground whole grain products are generally easy to digest. In addition, foods rich in tannic acid, pectin and potassium can be used to limit water and electrolyte loss. Tannic acid inhibits intestinal peristalsis and pectins bind water. The loss of cooking salt can be well compensated with normal salted food. Drinking 2-3 l a day also gives the possibility to influence the stool regulation. However, strong attention should be paid to the feeling of thirst. A daily urine volume of at least 1 liter per day is important.

For ileostomy patients who have a high output of more than 1000 ml, it is recommended not to drink still water, but to switch to electrolyte drinks or lightly sweetened tea. This optimizes the osmolarity.

In general, it is recommended to eat slowly and chew well. A diet low in irritants is more digestible and does not burden or irritate the stomach and intestinal mucosa, i.e. initially avoid highly sweetened, fried, roasted and spiced foods.

Living with a stoma does not mean having to renounce the joys of life!

The basis of nutritional therapy is the “light full diet”. The “light whole foods” diet avoids foods and beverages that experience has shown frequently lead to intolerances, such as: Legumes, mushrooms, cabbage, raw onions, garlic, leeks, fried foods, wholemeal bread with whole grains, freshly baked bread, hard-boiled eggs, acidic foods, strongly fried foods, smoked foods, spicy foods, foods and beverages that are too hot or too cold, carbonated beverages and unripe fruit. Shortly after surgery, fresh fruit (except bananas), salads, raw vegetables, tomatoes, cauliflower, peas and green beans may also be intolerable.

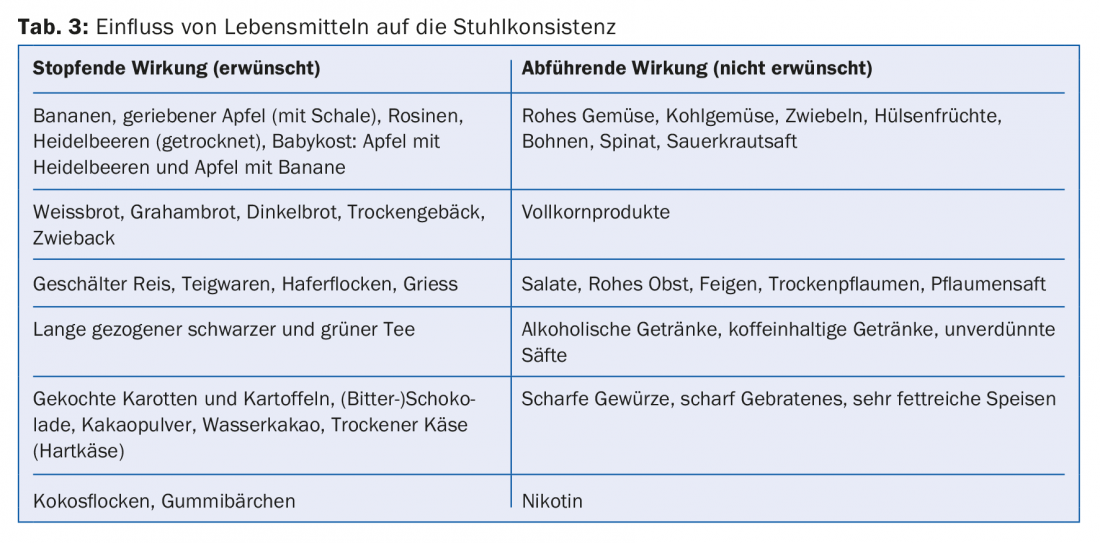

Tables 3 and 4 provide an overview of the influence of foods on stool consistency and intestinal gas formation.

Notes on nutrition for small bowel stoma

For the person concerned, it is important to know that any intake of food or drink leads to depletion. Eating and drinking slowly and chewing thoroughly can be very helpful here (Tab. 5).

For a long-term and preventive diet, it is recommended to change eating habits to those of the Mediterranean cuisine. The Mediterranean diet not only prevents coronary heart disease, but also obesity and certain forms of cancer.

Drug therapy recommendations

In addition to balancing the water and electrolyte balance and vitamin substitution, inhibition of motility is the main focus of drug therapy. Imodium sublingual, codeine and opium tinctures are used. Bile acid binding is possible by cholestyramine. Binding of liquid can be easily achieved by pectins (e.g. dried apple powder). Reduction of gastric secretion is achieved by H2 blockers or proton pump inhibitors. Intestinal inhibition of secretion can be induced by somatostatin or octreotide if short bowel syndrome is imminent.

Take-Home Messages

- For any intestinal stoma, all involved in the treatment should know the reason for the stoma creation, the section of intestinal diversion, and the number of intestinal legs drained in order to provide optimal medical care.

- For patients, an ostomy represents a serious intervention with radical changes in body image and considerable psychological stress.

- Stoma complications are frequent despite adequate surgical technique and require competent and interdisciplinary management between primary care physician, stoma therapists, Spitex as well as surgeons.

Literature:

- Hirche Z, Willis S: Intesinal stomas. General and Visceral Surgery up2date 2014; 5: 299-314.

- Hirche Z, Willis S: Principles of stoma creation-measures for hernia prophylaxis. Chir Practice 2017; 83: 38-46.

- Colwell J, et al: Fecal and urinary diversions: management principles. 1st Edition; St. Louis, Mo., Mosby 2004.

- Aquina CT, et al: Parastomal hernia: A growing problem with new solutions. Dig Surg 2014; 31(4-5): 366-76.

- Carne PW, Robertson GM, Frizelle FA: Parastomal hernia. Br J Surg 2003; 90(7): 784-793.

- Israelsson LA: Parastomal hernias. Surg Clin North Am 2008; 88(1): 113-125.

- Shabbir J, Chaudhary BN, Dawson R: A systematic review on the use of prophylactic mesh during primary stoma. formation to provent parastomal hernia formation. Colorectal Dis 2012; 14(8): 931-936.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2018; 13(6): 14-18