Patients with epilepsy are less likely to be active in sports compared to healthy individuals, although in general a decrease in seizure frequency during moderate sports activity can be assumed. Seizure provocation by exercise is rare. In animal models, positive effects on epileptogenesis and seizure susceptibility have been shown by influencing neurotransmitter systems and inhibitory neurons, including upregulation of neurotrophic factors. Additionally, psychiatric comorbidities such as depression and anxiety disorders are positively affected. On the other hand, the risk of injury must be considered depending on the type of sport and the individual seizure frequency. An anticonvulsant effect of exercise has not yet been adequately demonstrated in humans.

Approximately one percent of the population suffers from epilepsy; in addition, epileptic seizures are a common complication of neurological diseases [1]. The majority of epilepsy patients exercise less frequently than healthy controls [2–5]. In a large European study, only 30% of epilepsy patients were active in sports, compared to 41% of healthy individuals [6]. It has also been shown that children and adolescents with epilepsy are less likely to exercise and more likely to be obese than their healthy siblings [4]. Objective measures can also be used to demonstrate reduced aerobic and muscular endurance [3] and muscle strength [7] in people with epilepsy. Lack of physical activity, in turn, increases the risk of obesity [3,4] and days of sick leave [8].

The reason for this lack of exercise is probably the fear of patients, their relatives and physicians of an increased risk of injury and seizure induction during sports activities, which makes individual patient counseling necessary in each case.

Anticonvulsant effect of sport

To date, no anticonvulsant effect of physical activity has been demonstrated, but predominantly beneficial effects of exercise on seizure frequency are reported in the literature. In two independent studies of large outpatient epilepsy clinics in Norway and Brazil, over 30% of respondents reported positive effects of regular training on seizure frequency [2,9].

Evidence from animal studies suggests that physical activity may also play a role in the primary prevention of epilepsy. A Swedish population-based study published in 2013 also showed evidence in humans that decreased cardiovascular fitness in 18-year-old male recruits is associated with an increased risk of epilepsy in later adulthood [10]. This allows the hypothesis that an improvement in cardiovascular fitness through exercise could have a protective effect with regard to the development of epilepsy.

The short-term effects of physical activity have been studied in children with focal and generalized epilepsy [11]. During exercise, 77% of the subjects experienced a decrease in epileptiform EEG changes, and this effect regressed in 85% after exercise was stopped.

Physiotherapy and structured exercise programs

There are few prospective study data on the effect of exercise on epilepsy disease. In the majority of these studies, no significant changes in seizure frequency were found, but positive psychosocial effects as well as reductions in sleep problems and fatigue were observed. In the European culture yoga does not belong to the common sports and is rather counted among the relaxation and meditation techniques. When using yoga in epilepsy patients, several studies have demonstrated beneficial effects [12] as well as an increase in quality of life.

Neurobiological effects of exercise on seizure susceptibility.

The exact effects of physical activity on seizure propensity and epileptogenesis are unknown, but some underlying neurobiological mechanisms have been proposed. These conjectures are predominantly based on the pilocarpine model of temporal lobe epilepsy in rats [13,14].

Influence of neurotransmitter systems: In physically active rats, epileptogenesis was protracted [15]. Similar effects were also observed by swimming exercises in the penicillin-induced animal model [16]. In contrast, norepinephrine deficiency may favor epileptogenesis in animal models [17]. Increased catecholamine concentrations were observed during sports training, which is why the assumption of a protective effect of norepinephrine release during sports was made.

Higher neural reserve: early postnatal physical activity was able to slow epileptogenesis and attenuate later motor seizure symptoms in rats [18]. Thus, exercise in adolescence could lead to higher neuronal reserve and protect against later brain diseases.

Neuroprotection: physical training leads to upregulation of neurotrophic factors and thus could lead to increased neuronal resistance to damage [19]. Evidence of increased hippocampal synaptic plasticity was found in trained mice compared to controls [20].

Inhibitory interneurons: animal models showed an increase in hippocampal inhibitory interneurons, which may have an anticonvulsant effect [21].

Psychological effects

Depression and anxiety disorders are common comorbidities in people with epilepsy. The treatment of these important complaints is of central importance for epilepsy sufferers. Thus, physical training had a positive impact in patients with depressive disorder, as shown in a meta-analysis of 32 studies [22]. Similarly, another meta-analysis demonstrated positive effects on symptoms of anxiety disorder [23]. The positive effect of exercise on psychiatric comorbidities has also been demonstrated in people with epilepsy.

Sport risk

Despite the known beneficial effects of exercise in people with chronic diseases, patients with epilepsy have long been discouraged from exercising. As late as 1968, the American Medical Association (AMA) had recommended abstinence from sports for epilepsy patients [24]. This opinion was relaxed in light of new findings until 1974, when the possibility of participation in contact sports was also granted [25].

Essentially, the presumed sports-related risk relates to seizure provocation by sports activity and increased risk of injury if epileptic seizures occur. This continues to be reflected in the uncertainty of patients and physicians despite some educational work in recent years. For example, Steinhoff et al. [3] reported a fear of sports-associated seizures in 41% of epilepsy patients and seizure-associated injuries in 40%.

Seizure provocation through sports

Triggering of epileptic seizures during exercise has been postulated to be caused by severe fatigue, sleep deprivation, dehydration, electrolyte loss, hypothermia, or hypoglycemia [26]. Indeed, such changes may lead to provocation of epileptic seizures, but this seems to be the case only in rare extreme situations. Several clinical studies have failed to establish a relationship between physical exertion and the occurrence of epileptic seizures [27–30]. In addition, a reduction in interictal epileptiform discharges and desynchronization during exercise have been observed in several electroencephalographic studies [11,31,32]. Hypercapnia, stress reduction, or increased GABA activity during exercise have been discussed as underlying seizure-protective mechanisms. In addition, the increased alertness and vigilance immediately during exercise could be protective [33].

Nevertheless, there is no question that certain patients suffer more epileptic seizures during physical exertion. In these patients, an EEG recording under ergometric stress demonstrated an increase in interictal epileptiform activity [27,34]. Thus, EEG ergometry could provide a simple diagnostic tool to detect those epilepsy patients who are prone to sports-associated seizures. Accordingly, the individual consultation will then be able to take place.

Risk of injury

The overall risk of injury in patients with epilepsy, although only slightly increased compared to the healthy population, is definitely increased (17 vs. 12% in 12 months), as shown in a prospective European study [35]. However, the risk of severe or repeated traumatic brain injury is increased by more than 50% [36]. The proportion of sports-associated injuries, on the other hand, is up to three times lower in epilepsy patients than in healthy individuals [25], which is probably related to greater precautions and the lower level of sports activity in epilepsy patients.

Certain physical activities carry greater risks of injury than others. Swimming accidents are the most common sport-associated cause of death in patients with epilepsy [37]. Adults with epilepsy have a fourfold increased risk of drowning, and children have as much as a seven- to fourteenfold increased relative risk [38]. Sports activities at high altitudes or high speeds carry an epilepsy-independent risk of potentially serious injury to participants and spectators.

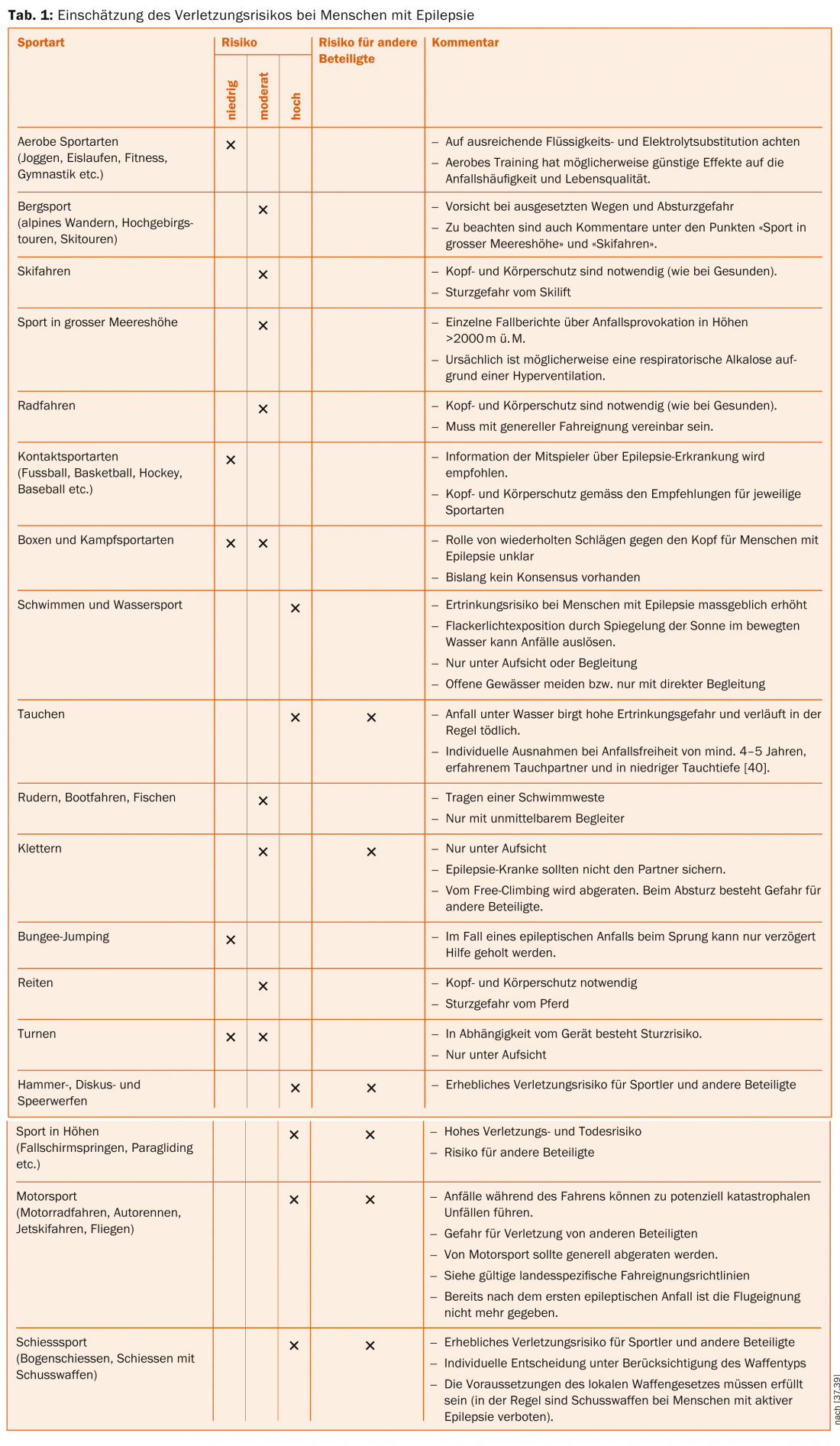

Sporting activity should be encouraged as a matter of principle. Many sports are possible for people with epilepsy [39]. The individual case requires an individual clarification with consideration of the type of sport, seizure type and seizure frequency as well as drug treatment. Table 1 shows an overview of risk assessment for individual sports.

With seizure freedom lasting for a year or more, almost all sports can be played. Epilepsies that are not accompanied by impaired consciousness are also usually unproblematic. Significantly more limitations are present in seizures associated with impaired consciousness and transition to generalized tonic-clonic seizures. If there are time-of-day differences in the occurrence of seizures, it is important to avoid particularly high-risk times of day. Special care should be taken when switching or discontinuing medications.

Literature:

- Hesdorffer DC, et al: Estimating risk for developing epilepsy: a population-based study in Rochester, Minnesota. Neurology 2011 Jan 4; 76: 23-27.

- Nakken KO: Physical exercise in outpatients with epilepsy. Epilepsia 1999; 40: 643-651.

- Steinhoff BJ, et al: Leisure time activity and physical fitness in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsia 1996; 37: 1221-1227.

- Wong J, Wirrell E: Physical activity in children/teens with epilepsy compared with that in their siblings without epilepsy. Epilepsia 2006; 47: 631-639.

- Bjørholt PG, et al: Leisure time habits and physical fitness in adults with epilepsy. Epilepsia 1990; 31: 83-87.

- RESt-1 Group: Social aspects of epilepsy in the adult in seven European countries. The RESt-1 Group. Epilepsia 2000; 41: 998-1004.

- Jalava M, Sillanpää M: Physical activity, health-related fitness, and health experience in adults with childhood-onset epilepsy: a controlled study. Epilepsia 1997; 38: 424-429.

- Chong J, et al: Behavioral risk factors among Arizonans with epilepsy: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System 2005/2006. Epilepsy Behav 2010; 17: 511-519.

- Arida RM, et al: Evaluation of physical exercise habits in Brazilian patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2003; 4: 507-510.

- Nyberg J, et al: Cardiovascular fitness and later risk of epilepsy: a Swedish population-based cohort study. Neurology 2013; 81: 1051-1057.

- Nakken KO, et al: Does physical exercise influence the occurrence of epileptiform EEG discharges in children? Epilepsia 1997; 38: 279-284.

- Ramaratnam S, Sridharan K: Yoga for epilepsy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000; CD001524.

- Arida RM, Scorza FA, Cavalheiro EA: Favorable effects of physical activity for recovery in temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia 2010; 51 Suppl 3: 76-79.

- Arida RM, et al: Experimental and clinical findings from physical exercise as complementary therapy for epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2012 Oct. 22; DOI: 10.1016/j.yebeh. 2012.07.025.

- Arida RM, de Jesus Vieira A, Cavalheiro EA : Effect of physical exercise on kindling development. Epilepsy Res 1998; 30: 127-132.

- Tutkun E, Ayyildiz M, Agar E: Short-duration swimming exercise decreases penicillin-induced epileptiform ECoG activity in rats. Acta Neurobiol Exp (Wars) 2010; 70: 382-389.

- Bortolotto ZA, Cavalheiro EA: Effect of DSP4 on hippocampal kindling in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 1986; 24: 777-779.

- Gomes da Silva S, et al: Early physical exercise and seizure susceptibility later in life. Int J Dev Neurosci 2011; 29: 861-865.

- Cotman CW, Berchtold NC: Exercise: a behavioral intervention to enhance brain health and plasticity. Trends Neurosci 2002; 25: 295-301.

- van Praag H, et al: Running enhances neurogenesis, learning, and long-term potentiation in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1999; 96: 13427-13431.

- Arida RM, et al: Differential effects of spontaneous versus forced exercise in rats on the staining of parvalbumin-positive neurons in the hippocampal formation. Neurosci Lett 2004; 364: 135-138.

- Rimer J, et al: Exercise for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; CD004366.

- Larun L, et al: Exercise in prevention and treatment of anxiety and depression among children and young people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006; CD004691.

- American Medical Association Committee on the Medical Aspects of Sports: Convulsive disorders and participation in sports and physical education. JAMA 1968; 206: 1291.

- Corbitt RW, et al: Editorial: Epileptics and contact sports. JAMA 1974; 229: 820-821.

- Lim KS: Sports and safety in epilepsy [Internet]. neurology-asiaorg [cited 2012 Nov 11]; Available at: www.neurology-asia.org/articles/20103_025.pdf (last accessed 11 Nov 2012).

- Nakken KO, et al: Effect of physical training on aerobic capacity, seizure occurrence, and serum level of antiepileptic drugs in adults with epilepsy. Epilepsia 1990; 31: 88-94.

- McAuley JW, et al: A Prospective Evaluation of the Effects of a 12-Week Outpatient Exercise Program on Clinical and Behavioral Outcomes in Patients with Epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2001; 2: 592-600.

- Millett CJ, et al: A study of the relationship between participation in common leisure activities and seizure occurrence. Acta Neurol Scand 2001; 103: 300-303.

- Camilo F, et al: Evaluation of intense physical effort in subjects with temporal lobe epilepsy. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2009; 67: 1007-1012.

- Götze W, et al: Effect of physical exercise on seizure threshold (investigated by electroencephalographic telemetry). Dis Nerv Syst 1967; 28: 664-667.

- Horyd W, et al: Effect of physical exertion on seizure discharges in the EEG of epilepsy patients. Neurol Neurochir Pol 1981; 15: 545-552.

- Vissing J, Andersen M, Diemer NH: Exercise-induced changes in local cerebral glucose utilization in the rat. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1996; 16: 729-736.

- Ogunyemi AO, Gomez MR, Klass DW: Seizures induced by exercise. Neurology 1988; 38: 633-634.

- Beghi E, Cornaggia C, RESt-1 Group: Morbidity and accidents in patients with epilepsy: results of a European cohort study. Epilepsia 2002; 43: 1076-1083.

- Wilson DA, Selassie AW: Risk of severe and repetitive traumatic brain injury in persons with epilepsy: A population-based case-control study. Epilepsy Behav 2014; 32: 42-48.

- Howard GM, Radloff M, Sevier TL: Epilepsy and sports participation. Curr Sports Med Rep 2004; 3: 15-19.

- Wirrell EC: Epilepsy-related injuries. Epilepsia 2006; 47 Suppl 1: 79-86.

- Saher S, Bauer J: Mobility and epilepsy. Steinkopff 2006.

- Almeida MDRG, Bell GS, Sander JW: Epilepsy and recreational scuba diving: an absolute contraindication or can there be exceptions? A call for discussion. Epilepsia 2007; 48: 851-858.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2015; 13(1): 4-9.