To date, no consistent definition of fecal incontinence can be found in the scientific literature. The topic remains a subject of scientific debate. The following article provides an overview of the etiology and the multiple avenues of diagnosis. If conservative therapeutic approaches do not work, invasive surgical measures should be considered.

Fecal incontinence is defined as involuntary loss of stool or the inability to control the evacuation of stool. Clinically, passive incontinence (involuntary loss of stool or wind that is not perceived by the affected person) can be distinguished from urge incontinence (loss of stool despite attempts to retain bowel contents) and fecal smearing (normal stool evacuation followed by fecal smearing) [1].

A combination of symptomatology is common. The psychological burden is great in most cases. It is not uncommon for incontinence to lead to social isolation because of the fear of unwanted stool loss [2]. Only about one third of those affected go to the doctor because of incontinence problems [3].

Epidemiology and costs

About 8% of the adult population is affected by fecal incontinence. Prevalence increases with age. According to estimates, 30-50% of nursing home residents suffer from incontinence [1, 4, 5]. This has major socio-economic implications. The magnitude of the incontinence problem is illustrated by the fact that more money is spent on fecal and urinary incontinence treatments than on malignancy therapy in the United States [1].

Etiology

Fecal incontinence may be mainly due to a change in stool consistency, structural (involving the rectum or sphincter apparatus), or functional [6]. The following complexes of causes can be distinguished:

Changes in stool quantity and quality: Causes of fecal incontinence are often diarrhea (e.g., in the context of chronic inflammatory bowel disease or irritable bowel syndrome) and marked constipation with stool retention (e.g., due to dyssynergic defecation or medication).

Structural disorders: Structural disorders of the rectum occur in the presence of rectal prolapse or hyper- or hyposensitivity. The most common causes of fecal incontinence at the level of the anal sphincter apparatus are obstetric or surgical trauma.

In women of reproductive age, birth trauma is the greatest risk factor for the development of incontinence [7]. Thus, a tear in the anal sphincter muscles was demonstrated in 35% of women (primipara) after vaginal delivery [7, 8].

Surgery in the anal region (e.g. surgical repair of hemorrhoids, anal fistulas or fissures) can cause damage to the sphincter apparatus, but this typically does not lead to incontinence until years later.

Functional disorders: Functional disorders are often associated with compromised anorectal sensory perception. This, in turn, may be due to birth trauma, but also to injury to the central or peripheral nervous system (e.g., traumatic paraplegic injury), as well as to nervous damage in the setting of diabetes mellitus or multiple sclerosis.

Other causes: fecal incontinence is common in old age, especially with additional dementia. Other causes of fecal incontinence may include diarrhea caused by food intolerance (e.g., lactose, sorbitol) or an adverse effect of certain medications (e.g., anticholinergics, muscle relaxants).

Diagnostics

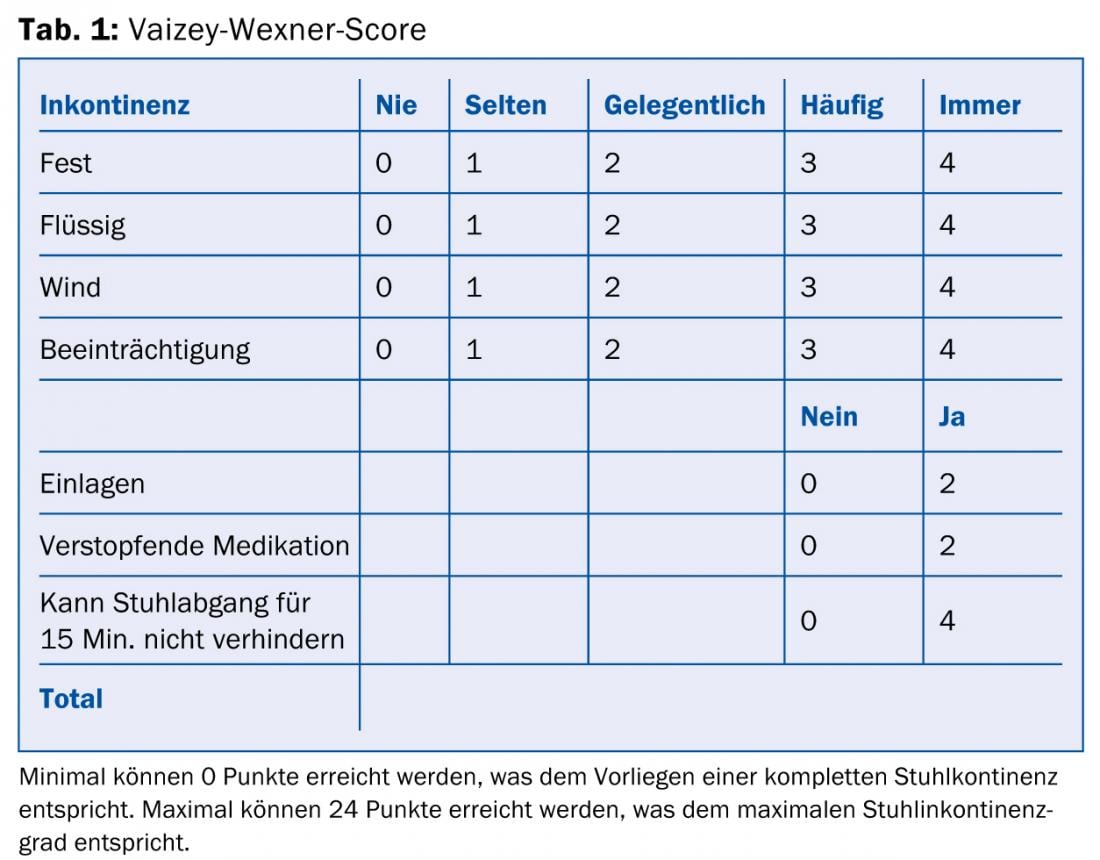

Important in the diagnosis is the explicit question about an existing fecal incontinence by the physician. Many patients do not discuss the symptoms of incontinence during the visit to the doctor because they are ashamed. Various questionnaires, such as the Vaizey-Wexner score (Table 1), are helpful for elicitation and objectification [9]. Moreover, it is important to know how the incontinence arose. These include questions about stool consistency (the Bristol tool chart can be used as an aid), vaginal deliveries, proctologic surgery, present systemic disease, and use of laxatives.

Inspection: Inspection at rest reveals prolapsing hemorrhoidal cushions, scars after previous surgery, possible fistulae, etc. A rectal or anal prolapse is unmasked in the pressing test.

Digital rectal examination: The digital rectal examination (DRU) provides information about sphincter tone (resting and clamping pressure) and contractility of the pelvic floor muscles. If appropriate, fecal impaction or a tumor mass is palpable, which may have an impact on continence. During synchronous vaginal and rectal examination, palpatory visualization of a rectocele is also possible in the female patient.

Endoanal ultrasound and endoanal MRI: Endoanal ultrasound allows assessment of the structural integrity of the sphincter apparatus and partially of the puborectalis loop. Local damage, such as loss of substance, defects or scars can be visualized [10]. The introduction of three-dimensional ultrasound technology, which is available to specialized centers, has further increased the accuracy of this examination.A comparison of endoanal ultrasound with endoanal MRI showed no significant difference in the detection of sphincter defects. Thus, endoanal sonography is the method of choice [1, 11].

Anal manometry and defecography: In defecography, the pelvic floor is examined in various positions (rest, pelvic floor contraction, pressing).

Anal manometry allows objective pressure measurement of the sphincter apparatus both at rest and during tension. In addition, the length of the functional portion of the anal canal can be determined. The functioning, healthy sphincter has a resting pressure of about 60-80 mmHg. By activating the external sphincter, this occlusion pressure can be increased arbitrarily to about 120-140 mmHg. The normal clamping time is >10 seconds.

A new feature is three-dimensional high-resolution anal manometry, which allows simultaneous three-dimensional acquisition of physiologic and topographic data [12].

Endoscopy: Because inflammatory processes, benign and malignant tumors can also affect continence, endoscopic examination is also an important part of the incontinence assessment.

Therapeutic approaches

Any therapy first includes stool regulation, with the aim of normalizing the consistency of stool and prolonging the time of stool passage in the intestine. Liquid stool is much more poorly retained by a damaged continence organ than formed stool. It is important to have a high fiber content in the diet. In addition to the intake of fruits, vegetables, legumes and whole grain products, swelling agents have a supporting effect (e.g. Metamucil® = psyllium).

If excessively soft stools or stool frequency persists despite these measures, loperamide (Imodium®) may help [13].

Physiotherapeutic measures of the biofeedback type are used in selected cases in addition to the above-mentioned drug therapy. Biofeedback therapy should be performed mainly in the presence of positive predictive factors (motivated patient, rectal perceptions weak, intact sphincter apparatus, urge incontinence) [14].

Surgery

If the conservative, i.e. non-surgical therapies do not result in a decisive improvement of the conti-nence, surgery should be considered as a therapeutic measure. Eligible:

Sphincter repair: If the cause of incontinence is a defective sphincter apparatus, the existing muscle defect can be repaired by means of sphincter repair. This operation is usually performed in younger patients, especially in the presence of an external nerve defect <120 ° (usually for incontinence after birth trauma).

Sacral neuromodulation: the operation proceeds in two phases, a test phase and (if the test stimulation is successful) a definitive implantation. In the test phase, a trial electrode is first inserted under local anesthesia in the area of the S3 or S4 nerve root of the sacrum and connected to an external stimulator. This is usually followed by three weeks of test stimulation. A stool diary is consulted to assess the success of therapy. If an improvement in symptoms of at least 50% is achieved during the test phase, this is an indication for definitive stimulator implantation. In contrast to sphincter reconstruction, the long-term success rate of sacral neuromodulation is 89%, with 53% of patients experiencing greater than 50% improvement in incontinence symptoms and 36% of patients becoming fully continent [15]. It is therefore now considered the most promising invasive therapy for fecal incontinence.

Dynamic gracilisplasty: Dynamic gracilisplasty can be performed especially in the presence of a large substance defect of the sphincter muscles due to severe trauma or failed surgical sphincter reconstruction.

In this procedure, the distal portion of the gracilis muscle is wrapped around the anus after surgical mobilization. However, because the patient is unable to permanently tense the muscle, a stimulation electrode is also implanted. For defecation, the muscle contraction can thus be stopped by means of a remote control. When the stimulator is switched on again, the gracilis muscle tightens again and the anus closes. Because of the high complication rate, this procedure is now very rarely used.

Artificial neo-sphincter: The indications for implantation of an artificial neo-sphincter are the same as those for dynamic gracilisplasty. The artificial sphincter consists of a silicone sleeve which is placed around the anus. The cuff is connected via a tube to a pump, which is placed in the scrotum in men and in the labium majus in women. The pump is also connected to a pressure-regulating balloon via a second hose, which is housed in the Cavum Retzii. The sphincter can be controlled mechanically via the sphincters in the scrotum resp. control pump placed in the labium majus [16]. As with dynamic gracilisplasty, morbidity is also very high with this procedure. Accordingly, the indication for surgery must be very strict.

The less than satisfactory results of the neo-sphincters described above spurred research: Thus, in 2010, the implantation of a magnetic artificial sphincter consisting of several titanium spheres with a magnetic core was described for the first time. This is to strengthen the natural continence organ and prevent incontinence episodes. Defecation is possible in the normal way against the magnetic resistance. Whether this magnetic sphincter will achieve good results remains to be seen [17].

Sphincter augmentation: Sphincter augmentation is used especially in cases of mild passive incontinence (e.g., weakness or defect of the internal sphincter muscle). The most common materials are collagen, silicone or autologous fat. The substances are injected submucosally or intersphincterally. Most studies have demonstrated only a short-term improvement in incontinence.

Although the therapy is simple, its success is questionable; long-term studies are lacking. In addition, the high price must be mentioned: Silicone therapy is not a mandatory service and is currently not paid by health insurance companies, which means that the patient can be charged at least 3000 – 4000 CHF.

Colostomy: The placement of a colostomy should be considered especially if the patient requires additional assistance for each toilet visit, e.g., in wheelchair-dependent or completely immobile patients [18]. The quality of life of patients with conventionally refractory fecal incontinence improves significantly after colostomy placement [19].

CONCLUSION FOR PRACTICE

- The prevalence of fecal incontinence is 8%.

- Only one third of those affected seek medical advice. This mostly out of shame.

- Conservative therapy primarily includes high-fiber diet, Metamucil®, loperamide, and biofeedback.

- The most successful invasive therapy is sacral neuromodulation.

PD Antonio Nocito, MD

Literature:

- Rao SS, et al: Diagnosis and management of fecal incontinence. Am J Gastroenterol 2004 Aug; 99(8): 1585-1604.

- Norton NJ: The perspective of the patient. Gastroenterology 2004; 126: S175-S179.

- Johanson JF, et al: Epidemiology of fecal incontinence: the silent affliction. Am J Gastroenterol 1996 Jan; 91(1): 33-36.

- Saga, et al: Prevalence and correlates of fecal incontinence among nursing home residents: a population-based cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatrics 2013; 13: 87.

- Rudolph W, et al: A practical guide to the diagnosis and management of fecal incontinence. Mayo Clin Proc 2002 Mar; 77(3): 271-275.

- Lazarescu A, et al: Investigating and Treating fecal incontinence: when and how. Can J Gastroenterol 2008; 23(4): 301-308.

- Kamm MA: Obstetric damage and fecal incontinence. Lancet 1994; 344: 730-733.

- Sultan AH, et al: Anal sphincter disruption during vaginal delivery. NEJM 1993; 329: 1905-1911.

- Vaizey CJ, et al: Prospective comparison of faecal incontinence grading systems. Gut 1999 Jan; 44(1): 77-80.

- Sultan AH, et al: Anal endosonography and correlation with in vitro and in vivo anatomy. BJS 1993; 80: 508-511.

- Dobben AC, et al: External anal sphincter defects in patients with fecal incontinence: comparison of endoanal MR imaging and endoanal US. Radiology 2007 Feb; 42(2): 463-471.

- Vitton V, et al: Comparison of three-dimensional high-resolution manometry and endoanal ultrasound in the diagnosis of anal sphincter defects. Colorectal Disease 2013; 15: e607-e611. doi:10.1111/codi.12319).

- Sun WM, et al: Effects of loperamide oxide on gastrointestinal transit time and anorectal function in patients with chronic diarrhea and faecal incontinence. Scand J Gastroenterol 1997 Jan; 32(1): 34-38.

- Prather CM: Physiologic variables that predict the outcome of treatment for fecal incontinence. Gastroenterology 2004 Jan; 126(1Suppl 1): S135-140.

- Hull T, et al: Long-term Durability of Sacral Nerve Stimulation Therapy for Chronic Fecal Incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum 2013; 56: 234-245.

- Christiansen J, et al: Implantation of artificial sphincter for anal incontinence. Lancet 1987 Aug 1; 2(8553): 244-245.

- 17 Lehur PA, et al: Magnetic Anal Sphincter Augmentation for the Treatment of Fecal Incontinence: A Preliminary Report From a Feasibility Study. Dis Colon Rectum 2010; 53: 1604-1610.

- Vaizey CJ, et al: Recent advances in the surgical treatment of faecal incontinence. BJS 1998; 85: 596-603.

- Catena F, et al: Untreatable faecal incontinence: colostomy or colostomy and proctectomy? Colorectal Dis 2002; 4(1): 48-50.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2014; 9(1): 17-22