A 48-year-old patient presents with chest pain and volume regurgitation that do not improve despite treatment with standard-dose PPI preparations.

Background: A 48-year-old male patient presented to an endocrinologist with intermittent chest pain and regurgitation of acid gastric contents. According to the patient, the symptoms last for hours after meals and wake him up at night. The patient also complained of occasional constipation and nausea, but rarely vomited. Treatment with the standard dose of proton pump inhibitors (PPI) (pantoprazole 1x20mg per day) had improved chest pain, but the other symptoms persisted. The patient had recently lost 5 kg and had type 1 diabetes developed in childhood. In recent years, his glycemic control was acceptable (Hba1c 6.1%). Nevertheless, he was already under treatment for retinopathy, peripheral neuropathy, and microalbuminuria with mild renal insufficiency. The patient is a non-smoker, does not drink alcohol and is on continuous therapy with insulin, acetylsalicylic acid and ramipril.

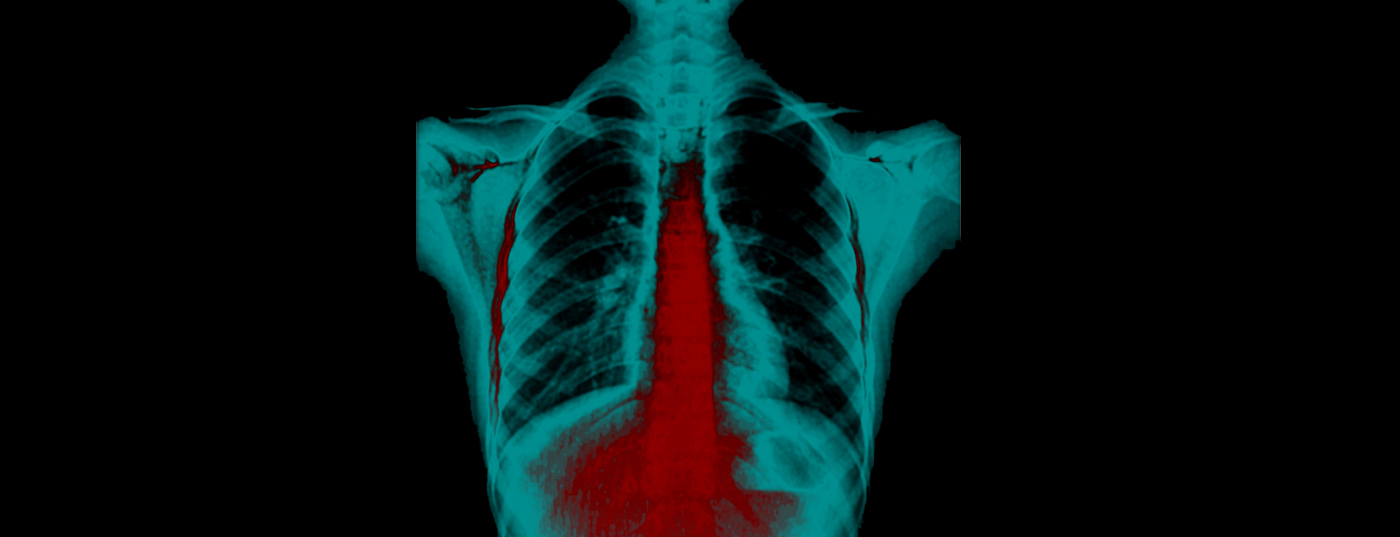

History and diagnosis: Gastroscopy was performed to clarify the persistent symptoms. This revealed moderate reflux esophagitis (grade B) with multiple erosions in the distal esophagus despite acid suppression therapy. The stomach did not contain any food. No evidence of hiatal hernia was noted. Subsequently, the PPI dose was increased (pantoprazole 2x40mg per day), without significant improvement of symptoms. High-resolution manometry and 24-hour pH impedance measurement were ordered to determine the cause of the symptoms. Examination revealed mildly ineffective motility (40% effective swallows) and a normal esophago-gastric reflux barrier. There were no signs of rumination.

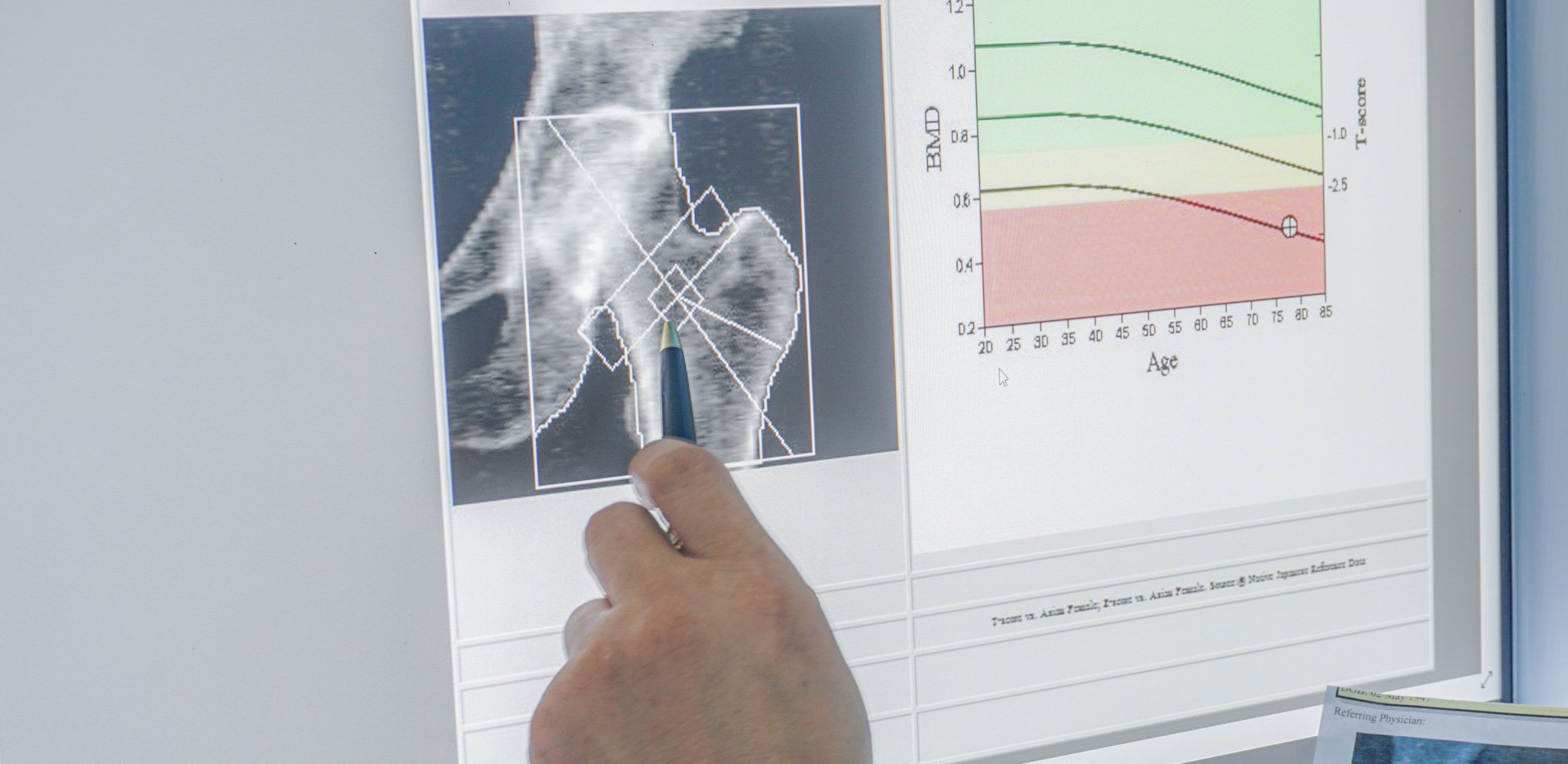

Therapy and Course: Despite these near-normal findings, there was severe pathologic acid exposure with prolonged esophageal reflux events during the day and especially at night. Symptoms were associated with proximal regurgitation of gastric contents. The severity of reflux disease was unexpected in a patient with near-normal motility and a mechanically intact reflux barrier. For this reason, a gastric emptying study was performed and pathological retention of the test meal, diagnosis gastroparesis, was detected. Therefore, treatment requires high-dose PPI therapy (e.g., pantoprazole 2x40mg per day), including lifestyle and dietary adjustments and ingestion of very soft, pureed, or liquid foods and avoidance of food intake 4 hours before bedtime. Prokinetic medications may also be helpful. In this case, prucalopride, a modern prokinetic with a good safety profile, was added to the acid-inhibiting drugs. This 5-HT4 agonist accelerates both gastric and colonic transit and provided good relief of upper gastrointestinal symptoms and constipation.

Comment by Prof. Mark Fox, MD : Gastroparesis is an important cause of reflux esophagitis that does not respond to standard-dose acid inhibitors. The slow gastric emptying also explains the long-lasting volume regurgitation. In this case, the clinical history of type 1 diabetes with complications was typical, but idiopathic gastroparesis is not uncommon.

Comment by Prof. Mark Fox, MD : Gastroparesis is an important cause of reflux esophagitis that does not respond to standard-dose acid inhibitors. The slow gastric emptying also explains the long-lasting volume regurgitation. In this case, the clinical history of type 1 diabetes with complications was typical, but idiopathic gastroparesis is not uncommon.

In the present case, the use of a modern prokinetic (prucalopride) led to success because its mechanism of action improves ineffective upper and lower GI tract motility. The most common side effect of this drug is diarrhea and this may limit its use in clinical practice.

Alternatively, regular administration of an alginate may be effective. This preparation stops the reflux of stomach contents and thus not only the acid complaints, but also relieves the volume regurgitation that disturbs sleep. Since alginates do not build up an active level in the body, they do not have to be taken off or on their own and can therefore be used flexibly in the symptomatic therapy of reflux symptoms. In the patient described, add-on therapy was scheduled for midday and evening to best cover symptom-loaded times.