This time, ORL emergencies were among the topics discussed at the GP afternoon at the USZ. What are the modern diagnostics and treatment of epistaxis? What decisions should be made in acute rhinosinusitis? These and other questions were answered by Prof. Dr. med. David Holzmann from the Department of Ear, Nose, Throat and Facial Surgery at the University Hospital Zurich. He emphasized that epistaxis, in particular, is an often underestimated condition that can be challenging for the treating physician and associated with uncomfortable treatments for the patient.

According to Prof. Dr. med. David Holzmann, Department of Ear, Nose, Throat and Facial Surgery at the University Hospital Zurich, one of the most important risk factors for epistaxis is the use of anti-aggregants such as Clopidogrel and Aspirin®. Epistaxis caused by anticoagulants such as coumarins is already less significant and better in outcome. In addition, hematologic disorders, trauma, alcohol, or hypertension may be responsible for epistaxis. The medical history includes the four S:

- Side(right, left, bilateral, anterior, posterior)

- Start(where, when, how, duration)

- Severity(hemorrhage to massive hemorrhage, first episode/repetitive).

- Systemicdisease or medication (hematologic, vascular).

“Patients sometimes describe the bleeding dramatically, as it is an impressive experience when you bleed from the head. That’s why it’s important to ask again exactly how severe the bleeding really is,” he says. In the work-up, you should check vital signs and circulation (blood pressure, pulse). In addition, placement of intravenous access is critical (before transport, twice in severe cases). “Better do this one too early, so you have it in case the patient collapses,” Prof. Holzmann advised. This is followed by local inspection with or without decongestant measures and finally treatment. Blood sampling provides important information in cases of oral anticoagulation (INR) and severe recurrent bleeding (Hb). The so-called THREAT scheme indicates when a bleed is particularly dangerous(trauma, hematologicdisease, “rear location” [hintere Lokalisation], transfusion need).

How to help the patient?

Important first-care measures for anterior nosebleeds include properly pinching the nose, sitting upright, and leaning forward to prevent swallowing the blood. “Blood is the best emetic. Besides, you don’t see what volumes of blood actually flow when the patient swallows everything,” the speaker said. “A cold pack in the neck is of no use. There is no evidence of decreased blood flow septally. What does help, interestingly, is ice sucking.”

Oxybuprocaine (1% Novesin®), for example, is used for anesthesia; xylometazoline 0.1% (Otrivin®) and adrenaline 1:1000 have a decongestant effect. “Patients with severe nosebleeds usually have to cough and sneeze, so they spread the blood all over the office. You can use a cape to protect the patient’s clothing. Do not forget to also protect yourself from contamination during treatment. Your medical practice staff will also thank you if you use environmental protection and cover the equipment,” says the expert. Examination aids include a lamp, speculum and (nasal) aspirator.

Most bleeding is located in the anterior nasal region. Local coagulation can be performed here with silver nitrate pins, for example. Bipolar forceps provide another option for focused coagulation. “With epistaxis patients, you must always have both hands available. Examination and treatment are easiest when someone else does the suctioning,” Prof. Holzmann explained.

Tamponade (e.g. using Rapid Rhino® 900) is a helpful form of therapy for posterior epistaxis, but is usually perceived as very unpleasant. The dual-chamber, self-moistening system with hydrocolloid coating is inserted slowly and carefully along the floor of the nose (horizontally) under surface anesthesia if possible. In doing so, one should pay attention to pressure points. It must remain in the nose for 48 hours. Special devices prevent aspiration.

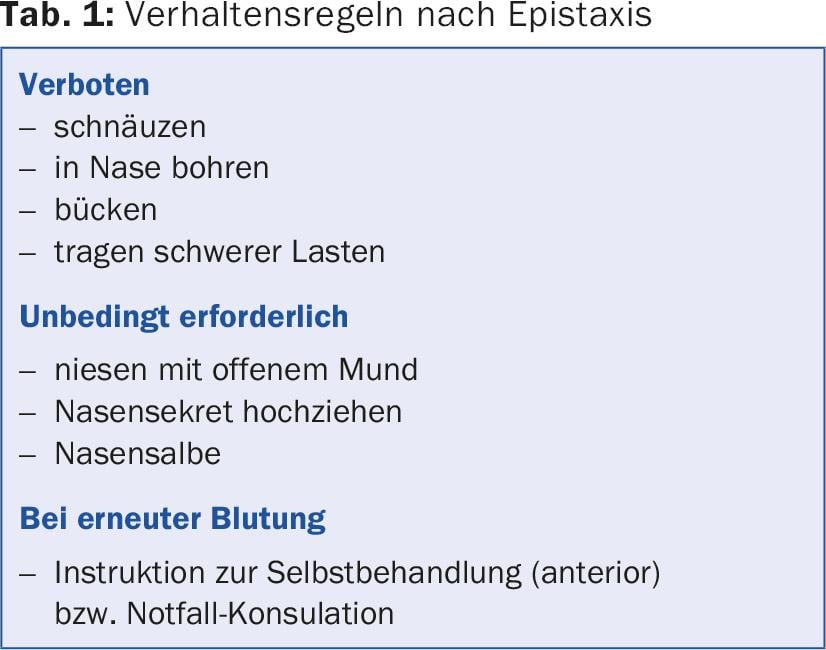

General rules of conduct after epistaxis are summarized in Table 1.

Acute rhinosinusitis

Acute rhinosinusitis is by far the most common case of a banal cold/rhinitis (acute viral). Postviral rhinosinusitis is found in significantly fewer patients and finally an acute bacterial form in a fraction. In adults, acute rhinosinusitis is defined as: Sudden onset of two or more symptoms lasting less than twelve weeks, one of which must be either nasal obstruction or runny nose (anterior/postnasal drip). Concomitant facial pain/pressure or reduction or loss of olfaction may occur. Severity can be assessed with rating scales such as the visual analog scale (VAS): mild (VAS 0-3), moderate (VAS >3-7), and severe (VAS >7-10).

Routine work-up in the practice includes external inspection (tapping dolence, sensory loss, orbita/ocular motility) and rhinoscopy (otoscope with large funnel, possibly swab middle nasal passage). A pus route posteriorly and dental problems can be clarified orally. Conventional X-ray is diagnostically unhelpful and therefore not indicated. If the clinic is severe, if complications are suspected, or if immunosuppression is present, a high-resolution CT (HR-CT) of the paranasal sinuses may be performed.

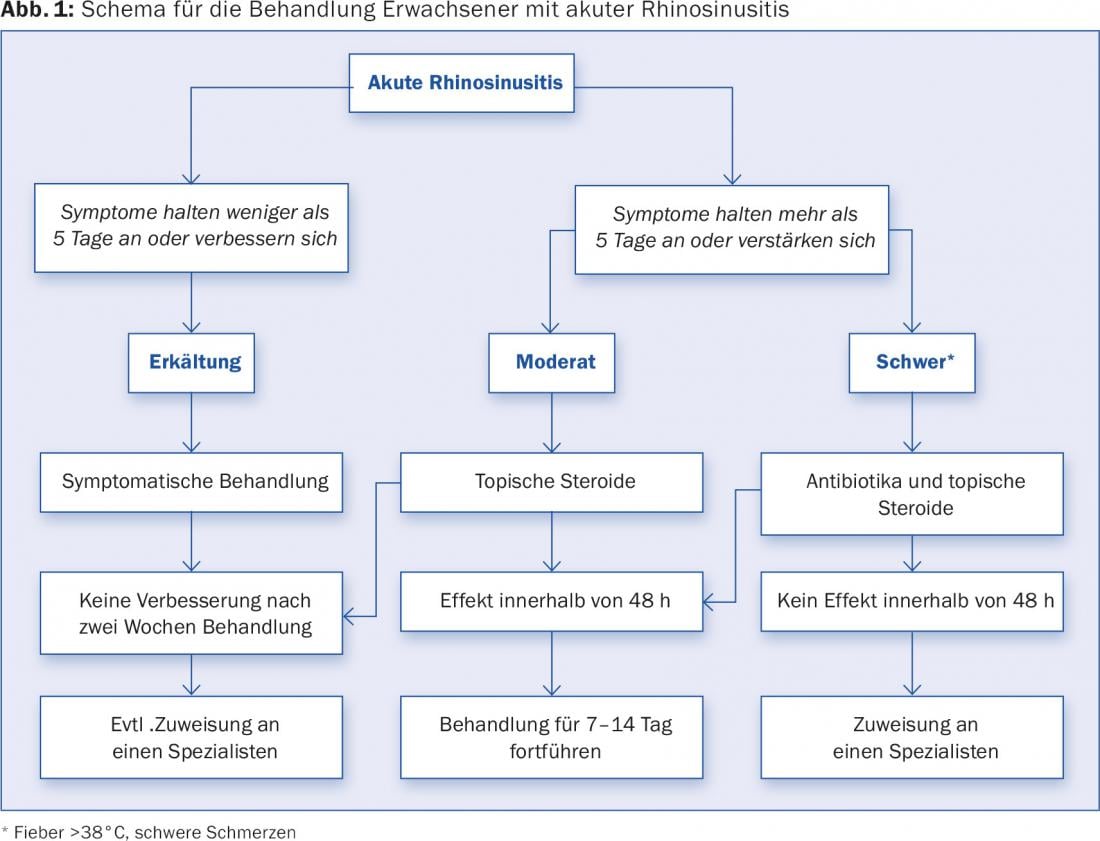

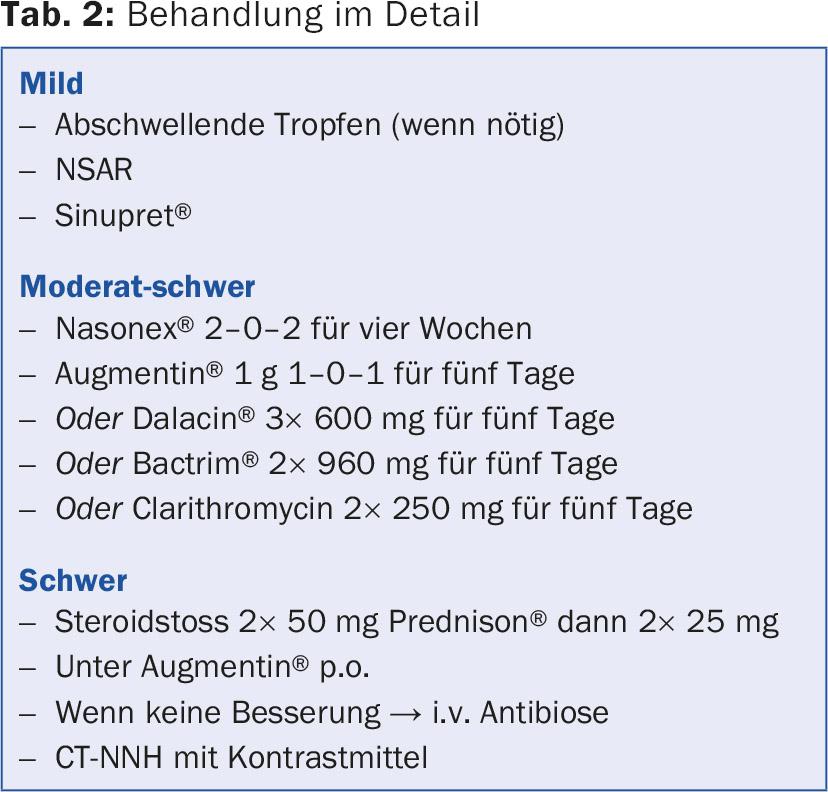

A scheme for the primary care of adult patients with acute rhinosinusitis is shown in Figure 1. Treatment options are presented in detail in Table 2. In addition, one should always be alert for warning symptoms that require immediate referral/hospitalization. These include:

- Periorbital edema

- Ophthalmoplegia

- Visual acuity loss

- Double images

- severe frontal headache unilateral or bilateral

- meningitic or other focal neurologic signs.

Source: 30th Interactive GP Afternoon, November 12, 2015, Zurich.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2015; 10(12): 42-44