Bullous autoimmune dermatoses are a clinically and immunopathologically heterogeneous group of rare autoimmune diseases. In patients of older age with pruritus and bulging blisters, bullous pemphigoid is at the top of the list of differential diagnoses. In patients with erosions in the area of the oral mucosa (“therapy-resistant stomatitis aphtosa”), possibly in combination with blisters/erosions on the keratinized skin, the presence of bullous autoimmune dermatosis should always be considered as a differential diagnosis. History regarding epistaxis, dysphagia, and dyspnea is essential in this case, as is close inspection of conjunctival and genital mucosa. Treatment of bullous autoimmune dermatoses should be performed in specialized centers. New therapeutic options such as rituximab and immunoadsorption allow even severe forms of the disease to be treated well in most cases. Target antigen determination is not only important for accurate diagnosis, but may also be indicative of the presence of a paraneoplastic process.

The bullous autoimmune dermatoses are a group of autoimmunological diseases that have in common the presence of autoantibodies against structural and adhesion molecules of the skin or mucosa. As a result of dysregulation of both adaptive humoral and cellular immunity, clefts develop that are clinically associated with blisters and erosions on skin and/or mucous membranes.

With regard to the localization of the cleft formation, it is possible to divide the bullous autoimmune dermatoses into two main groups for orientation:

1. Bullous autoimmune dermatoses with intraepithelial adhesion loss.

– Pemphigus diseases

2. bullous autoimmune dermatoses with subepithelial loss of adhesion.

– Pemphigoid diseases

– Linear IgA dermatosis

– Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita

– Dermatitis herpetiformis Duhring

Pemphigus diseases

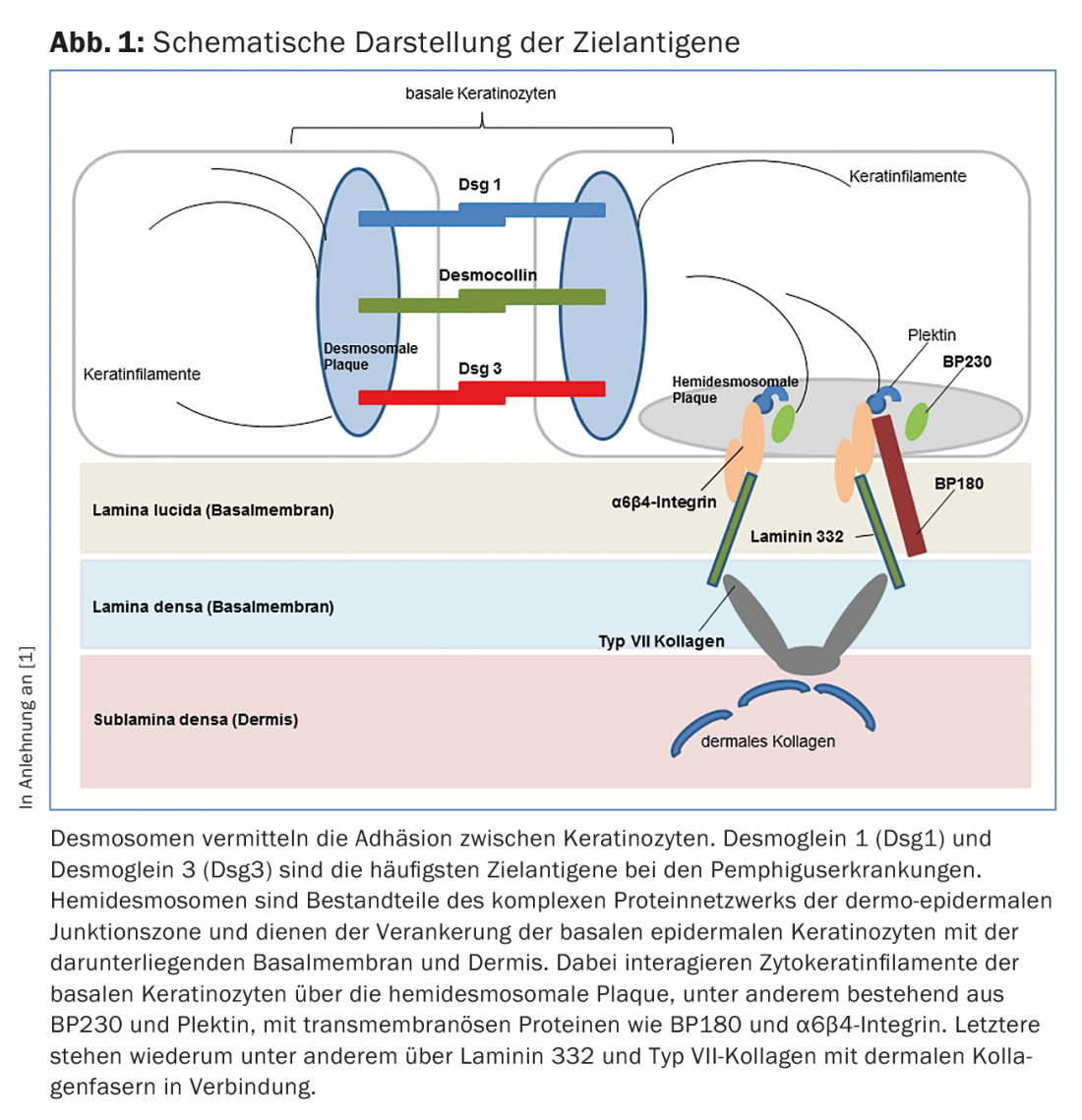

In diseases of the pemphigus group, loss of intraepithelial cell-cell contact occurs due to autoantibodies against proteins of the desmosomes (Fig. 1), resulting in superficial intraepidermal cleft formation. Clinically and immunopathologically, different forms of pemphigus can be distinguished.

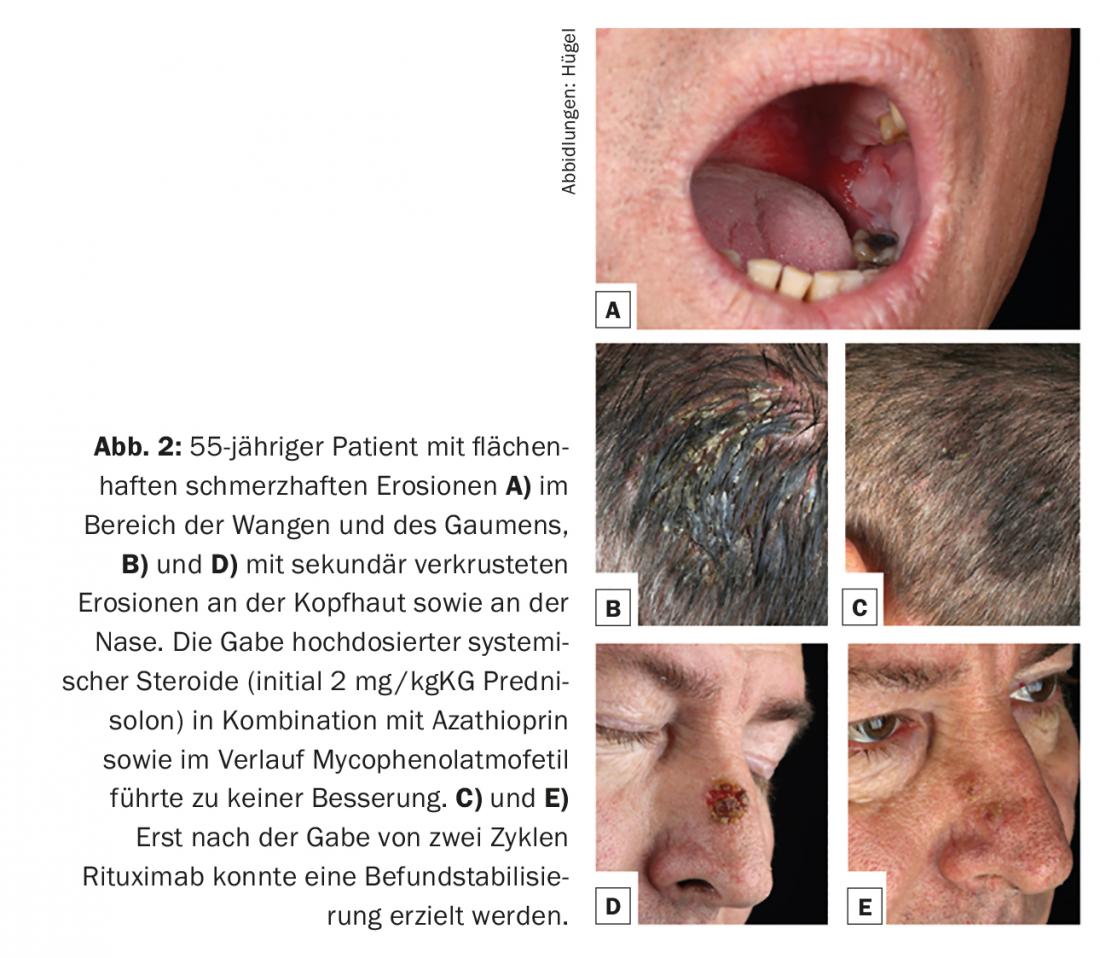

Approximately 80% of pemphigus cases are accounted for by pemphigus vulgaris, which manifests preferentially between the fourth and sixth decades of life and has an incidence of 0.1-0.5/100,000/year. Etiopathogenetically, autoantibodies against desmoglein 3 are always found. At the beginning of the disease, there are usually very painful enoral mucosal erosions (Fig. 2A) and it is not uncommon for the first presentation to a specialist in ear, nose and throat diseases. Optionally, antibodies against desmoglein 1 are also found in pemphigus vulgaris with consecutive infestation of the keratinized skin. (Fig. 2B and D). The clinical appearance of the skin is characterized by extremely vulnerable blisters with a thin blister canopy, which quickly rupture and therefore usually no longer present as blisters, but as (secondarily crusted) erosions. Nikolski phenomenon I (pushability of the upper epidermal layers by tangential traction on intact skin) can be elicited in clinical examination.

In contrast, in the second most common pemphigus disease – pemphigus foliaceus – autoantibodies are found only against desmoglein 1, but not desmoglein 3. In accordance with the expression pattern of the desmogleins, this disease therefore affects exclusively the keratinizing skin areas and not the mucous membranes. Here, too, intact blisters are almost never found, but areal erosions with sometimes leaf-like scaling. Skin manifestations often begin on the hairy head, face, or anterior and posterior sweat grooves and then spread to the periphery.

Paraneoplastic pemphigus, which is very rare, is particularly associated with hematologic malignancies (especially B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma) and has autoantibodies against both desmosomal and non-desmosomal targets. Clinically, it is characterized by extensive painful erosions and ulcers of the mucous membranes (especially mouth, lips, esophagus), conjunctival involvement, and polymorphous skin lesions.

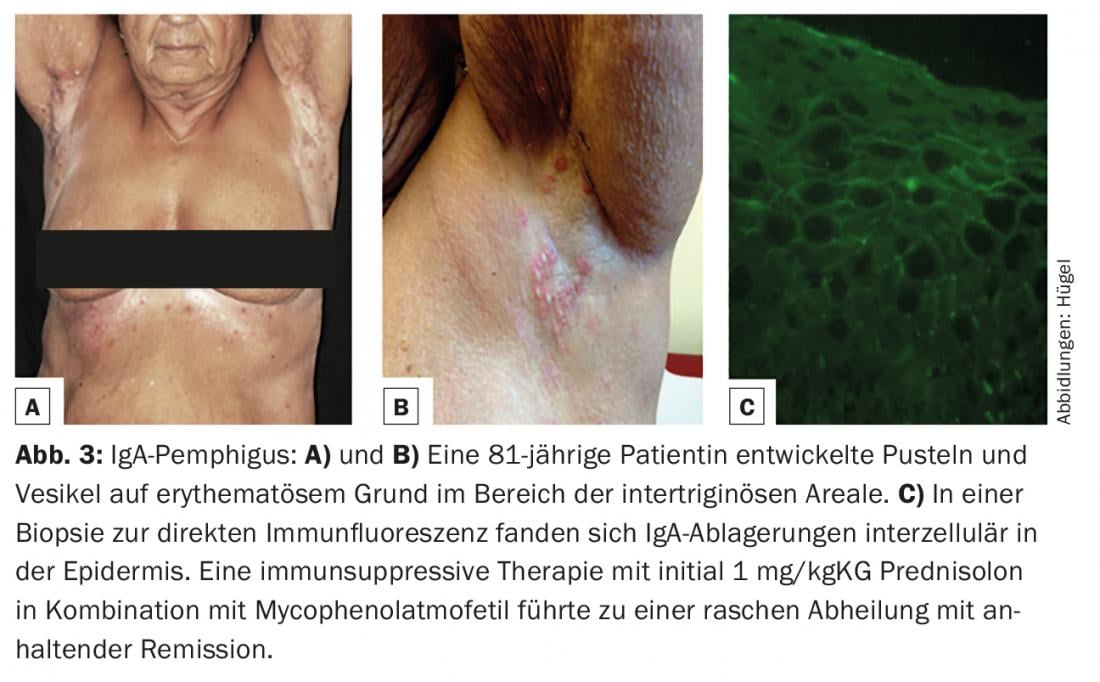

IgA pemphigus (characterized by intraepidermal IgA deposits on skin biopsy for direct immunofluorescence, Fig. 3C) is the rarest of the pemphigus variants. Clinically, pustules and vesicles on an erythematous base are found primarily in the intertriginous areas (Fig. 3A and B).

In all patients diagnosed with pemphigus, a careful medication history should be taken, since drugs such as penicillamine (which, however, is very rarely used nowadays in the treatment of rheumatic diseases), but also ACE inhibitors such as captopril, enalapril, or lisinopril, can induce pemphigus disease.

Blistering autoimmune dermatoses with subepithelial loss of adhesion.

In pemphigoid diseases, the blisters on the skin appear much more stable and plump than in pemphigus diseases due to the deeper subepidermal cleft formation. Patients often suffer from severe itching. The clinical picture is heterogeneous.

Bullous pemphigoid (BP) is the most common bullous autoimmune dermatosis, with an incidence of 12-21 cases per 1,000,000 population/year. The main age of onset is between the ages of 60 and 90, and as a result of the general increase in life expectancy, the incidence has risen sharply in recent years. A characteristic feature of bullous pemphigoid is the presence of autoantibodies against two hemidesmosomal structural proteins of the basement membrane zone: BP180 and/or (more rarely) BP230 (Fig.1). Clinically, bullous pemphigoid presents with bulging blisters filled with serous fluid, disseminated erythema, and urticarial lesions followed by erosions and crusts (Fig. 4A and B). The mucous membranes are affected to 10-30%. In a premonitory stage, the disease may progress for months to years without blistering. In elderly patients with severe pruritus and polymorphous skin lesions (eczema foci, urticarial-like plaques, excoriations as a consequence of pruritus), a prebullous stage of BP should therefore always be considered as a differential diagnosis.

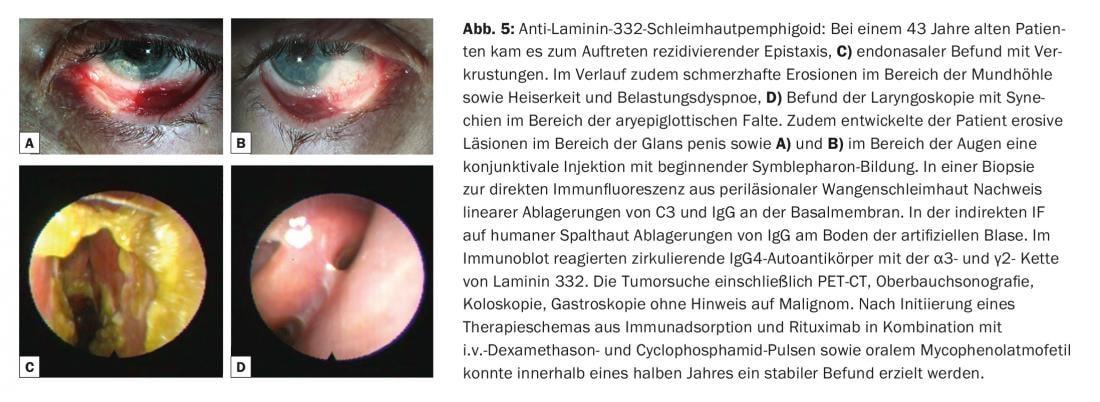

The term mucosal pemphigoid encompasses a heterogeneous group of rare diseases from the spectrum of bullous autoimmune dermatoses that are associated with subepithelial or subepidermal blistering and in which the chronic inflammatory changes occur predominantly in the mucosal region. Blistering is caused by autoantibodies against adhesion molecules of the dermo-epidermal junction zone, and at least ten different target antigens have been identified. Circulating IgG and/or IgA autoantibodies to BP180 are most commonly found. Less frequently, autoantibodies against BP230, laminin-332, α6β4-integrin, or collagen VII are detected (Fig. 1). Identification of the target antigen is of great importance, since in one subtype (anti-laminin-332 pemphigoid) an association with malignancy has been described in 30% of cases and tumor exclusion should be performed accordingly. Clinically, all mucous membranes with stratified squamous epithelium can be affected in mucous membrane pemphigoid. Most frequently, there is involvement of the oral mucosa, initially with a picture of desquamative gingivitis. Ocular involvement usually begins unilaterally with the clinical picture of conjunctivitis, in the course of which there is shortening of the conjunctival folds (fornices), symblepharon, trichiasis, synechiae and corneal atrophy with eventual risk of blindness. (Fig. 5A and B). Endonasal crusting, epistaxis, dysphagia, and hoarseness and stridor are found with nasopharyngeal involvement or laryngeal involvement, respectively (Fig. 5C and D). In men, genital infestations may cause adhesions between the glans penis and prepuce, and in women, obstruction of the introitus vaginae. Skin involvement – clinically similar to bullous pemphigoid – is found in about 20% of all cases.

Pemphigoid gestationis (PG) is a rare pregnancy dermatosis that can occur in the second and third trimesters or immediately postpartum and is pathophysiologically very close to bullous pemphigoid. As with this one, BP180 and – much more rarely – BP230 are the crucial target antigens. The cause of the development of autoantibodies has not yet been clarified. The HLA system seems to play an important role in genetic predisposition. It is discussed that the presentation of placental autoantigens together with paternal HLA class II molecules leads to an induction of autoantibodies. Clinically, the development of specific efflorescences is often preceded by a prodromal stage with intense pruritus. The skin lesions usually begin periumbilically (Fig. 6B) and may then spread throughout the integument. The most common lesions are urticarial papules and/or plaques, which occasionally appear cocadeniform. Only during the course do grouped vesicles or bulging blisters develop in most patients (Fig. 6).

Linear IgA dermatosis (LAD) is the most common autoimmune bullous dermatosis of childhood and then usually begins before the age of six. In adulthood, initial manifestation is possible at any age, but more commonly after age 60. Like mucous membrane pemphigoid, it is considered a heterogeneous clinical picture. Linear IgA-type deposits along the dermo-epidermal junction zone in skin biopsy for direct immunofluorescence are characteristic. IgA autoantibodies are most commonly directed against a 97-kDa protein (LABD-97) and a 120-kDa protein (LAD-1), which are generated by proteolytic cleavage of the extracellular portion of BP180. Clinically, anular or polycyclic blisters are frequently found on healthy or erythematous skin with preferential involvement of the face (especially perioral and ears), anogenital region, and less frequently on the trunk, hands, and feet. (Fig.7). Scarring and even blindness may occur on the mucous membranes, especially the conjunctiva, as in mucous membrane pemphigoid.

The clinical picture of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (EBA), in which IgG (and IgA) class antibodies to collagen VII are etiopathogenetically present (Fig. 1) , varies widely. In the mechano-bullous variant, the skin is highly vulnerable and blisters and erosions are found that heal scarred or with milia, especially in mechanically stressed areas such as the back of the hand, elbow, knee, sacral region and toes. In the inflammatory variants, this disease presents a clinical picture that can be difficult to distinguish from bullous pemphigoid or mucous membrane pemphigoid.

Dermatitis herpetiformis Duhring is a rare cutaneous subtype of the gluten-sensitive diseases. Several years ago, the epidermal transglutaminase (transglutaminase 3) and tissue transglutaminase (transglutaminase 2) can be identified. Patients with this disease develop papules and vesicles mainly on the extensor sides of the extremities, hairy head, gluteal and sacral. It is an extremely itchy condition. Therefore, Duhring’s disease should be considered in any patient with foreground scratch excoriations in the area of the aforementioned predilection sites.

Diagnosis of bullous autoimmune dermatoses

Skin biopsies for conventional histologic examination can be used to visualize the location of the cleft.

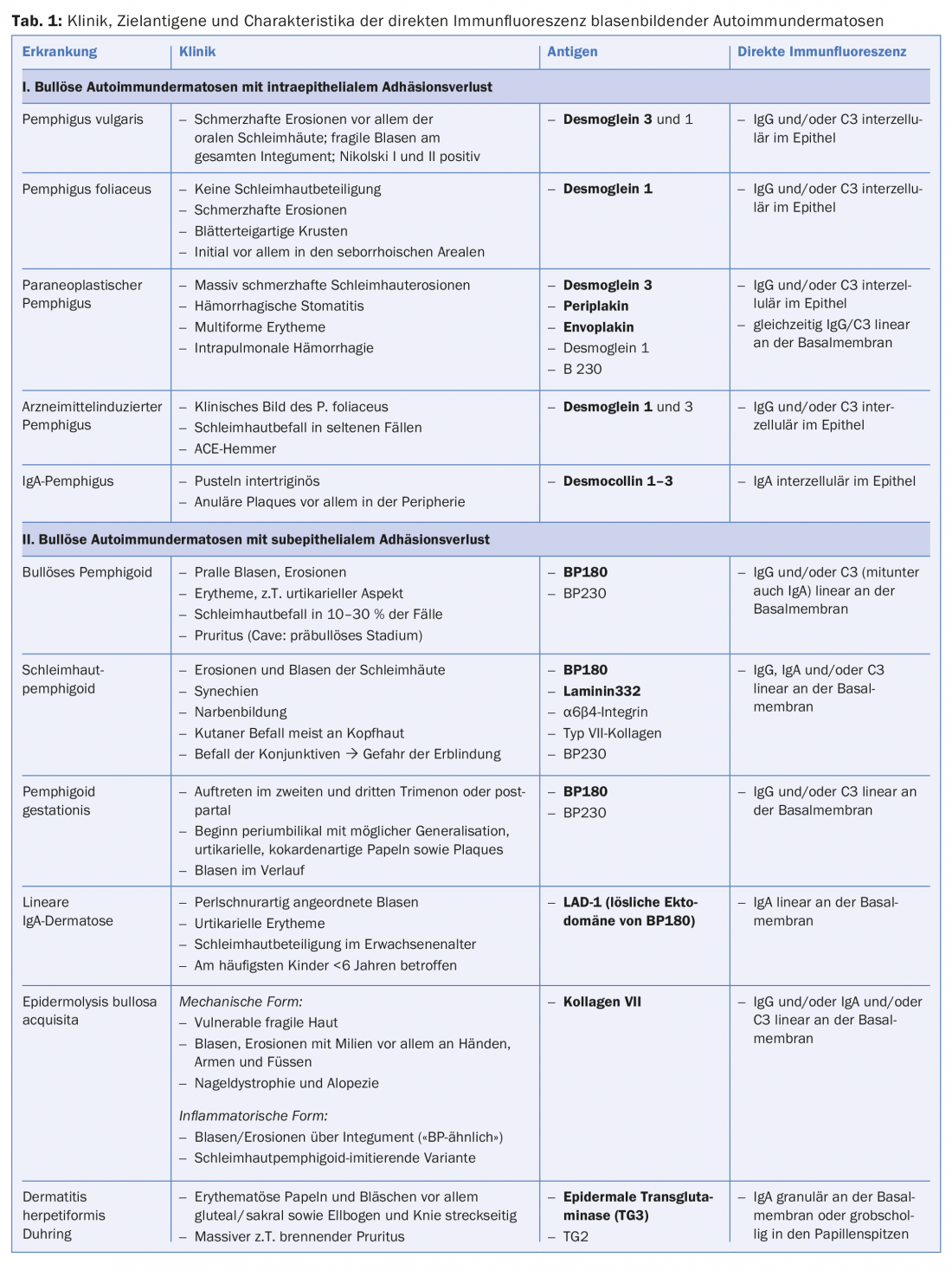

However, the diagnostic gold standard is the detection of tissue-bound autoantibodies (IgG, IgA and/or complement factor C3) in biopsies of skin or mucosa with direct immunofluorescence. The localization of the antibodies intercellularly in the epidermis or along the dermo-epidermal junction zone allows an immediate differentiation between the presence of a pemphigus disease or a disease from the spectrum of subepithelial bullous autoimmune dermatoses. If precipitates of the IgA isotype predominate, an IgA pemphigus (Fig. 3C), a linear IgA dermatosis or Duhring’s disease can be diagnosed, depending on the pattern (Tab. 1).

In addition to the (mucus) skin biopsies and for the exact characterization of the different subtypes, serological examinations are required. Indirect immunofluorescence on monkey esophagus and on human saline split skin has been established as a screening test for this purpose. Identification of target antigens is subsequently performed using various ELISA and, if necessary, specific immunoblot assays.

Autoantibody concentrations in the serum of pemphigus and pemphigoid patients usually correlate well with disease activity and are therefore also suitable for monitoring disease activity and assessing the need for further therapy.

Therapy of bullous autoimmune dermatoses

In general, the therapy of blistering autoimmune dermatoses depends on the severity on the one hand and the diagnosed subtype on the other hand. In the case of, for example, mild localized bullous pemphigoid, local treatment only with highly potent class IV steroids (clobetasol propionate 0.05% ointment) may be sufficient. In most cases, however, systemic corticosteroid administration in combination with other immunosuppressants (e.g., azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, cyclosporine, methotrexate, cyclophosphamide) is indicated. Dapsone is first-line agent for linear IgA dermatosis, dermatitis herpetiformis Duhring, and uncomplicated pure oral mucous membrane pemphigoid. In severe or refractory cases, intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG), immunoadsorption, and/or rituximab may be used. In addition, several case reports have been published in recent years demonstrating the efficacy of therapy with the anti-IgE antibody omalizumab in bullous pemphigoid. However, this requires further standardizing studies regarding dosage as well as duration of use.

The care of patients with blistering autoimmune dermatoses should be provided in specialized centers and requires – especially in the presence of a subtype with mucosal involvement – an interdisciplinary approach with involvement of ophthalmologists, otolaryngologists, dentists, gynecologists, gastroenterologists, and the dermatologic specialist as coordinator.

Literature:

- Schmidt E, Zillikens E: Diagnosis and therapy of bullous autoimmune dermatoses. Dtsch Arztebl International 2011; 108(23): 399-405.

Further reading:

- Hertl M (Ed.): Autoimmune Diseases of the Skin. Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, Management.3rd edition. Vienna – New York: Springer-Verlag 2011.

- Marazza G, et al: Incidence of bullous pemphigoid and pemphigus in Switzerland: a 2-year prospective study. Br J Dermatol 2009; 161(4): 861-868.

- Kneisel A, Hertl M: Autoimmune bullous skin diseases. Part 1: Clinical manifestations. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2011; 9(10): 844-856.

- Kneisel A, Hertl M: Autoimmune bullous skin diseases. Part 2: diagnosis and therapy. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2011; 9(11): 927-947.

- Kneisel A, Hertl M: Bullous pemphigoid: diagnosis and therapy. Wien Med Wochenschr 2014; 164(17-18): 363-371.

- Schmidt E, Zillikens D: Pemphigoid diseases. Lancet 2013; 381(9863): 320-332.

- Hertl M, et al: Recommendations for the use of rituximab (anti-CD20 antibody) in the treatment of autoimmune bullous skin diseases. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2008; 6(5): 366-373.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2017; 27(1): 18-25