At the EULAR congress in Paris, the question of what types of pain there are and how chronic, long-lasting pain can be treated was addressed. While normal acute pain is a sign of a well-functioning and self-protecting body, chronic pain, which presents without this warning function, is a major challenge.

(ag) According to Prof. Stefan Bergman, MD, Oskarström, pain is commonly defined as: an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage or described in terms of such damage (ISAP definition).

Two types of pain can be distinguished: acute and chronic. “Acute pain has a protective function. Not having a normal pain sensation is life-threatening. It serves as a kind of early warning system that sends signals before further damage is done. In addition, pain activates the stress system and provides information when latent pathological processes are taking place in the body. Long-lasting, chronic pain, on the other hand, no longer has any significance for the organism, but usually has a very complex cause,” he said. “Pain is said to be chronic either when it lasts more than three months or simply exceeds the expected time it takes for the body to heal the wound. Then it loses its function and becomes a problem.”

A causeless agony

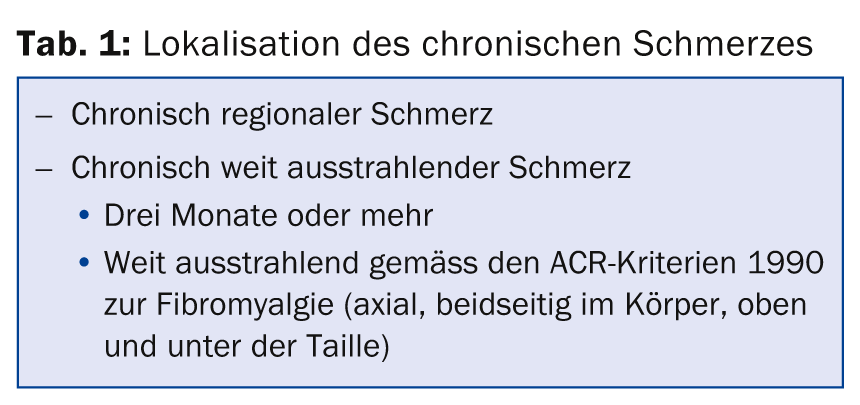

In rheumatology, pain is often nociceptive and associated with actual inflammation or damage. Neuropathic pain, as a result of direct injury to the nerves, can also usually be attributed to an obvious cause. However, when pain is prolonged, as described above, some people develop dysfunction in the nociceptive system, leading to phenomena such as fibromyalgia or loss of central pain signal inhibition. “Pain thus becomes an agony that no longer has an apparent cause, a disease in its own right, requiring other treatment considerations in addition to those for nociceptive and neuropathic pain,” Prof. Bergman explained. Table 1 lists the different types of chronic pain according to how they are distributed in the body.

Regarding epidemiology, it can be said that chronic pain is common. Musculoskeletal pain over three months of age occurs in 30-50% of all people, and this is predominantly back pain and, less commonly, pain that radiates widely (again, only a fraction of this is fibromyalgia). According to Prof. Bergman, it must also be noted that so-called “local” pain rarely actually remains local, but for example knee pain quickly radiates throughout the body in the majority of sufferers.

Therapy is urgently needed

A study has shown that chronic widely radiating pain can severely worsen the health condition in rheumatoid arthritis [1]. “Such pain must therefore be treated. The problem or the big challenge is only that the pain experience remains highly subjective and therefore an individual therapy strategy is inevitable,” the expert pointed out.

One possible therapeutic concept is preemptive analgesia [2], i.e., the introduction of an analgesic regimen before the onset of the noxious stimulus. This is to prevent sensitization of the nervous system to the following stimuli and thus an increase in pain. Of course, operations where the noxious stimulus can be accurately anticipated are particularly suitable for such an approach. The most effective agents are those that manage to keep the sensitization of the nervous system limited throughout the perioperative period.

Acute pain: The treatment of acute pain includes first of all the transfer of knowledge, above all also a realistic assessment of the further course. Painful examinations should be minimized as much as possible, especially in cases of tumors, infections, or fractures. Specific and time-limited pharmacologic therapies along with encouragement to return to normal daily activities are helpful.

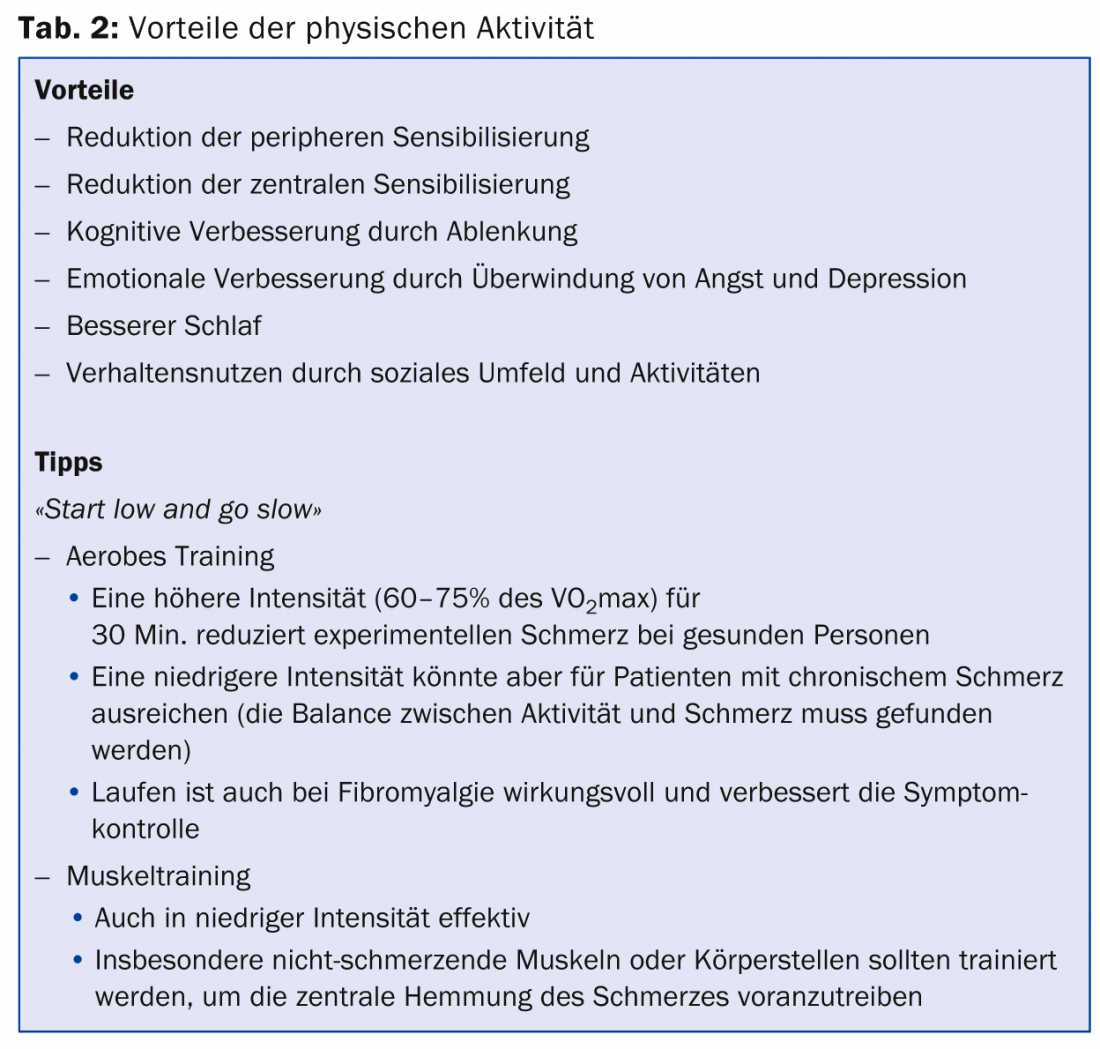

Chronic pain: cornerstones of treatment are physical activity (Tab. 2), cognitive approaches and pharmacological therapy. The bio-psycho-social and also a multidisciplinary approach is most effective.

Pharmacological options

For nociceptive pain, acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and COX2 inhibitors may be considered, according to Prof. Bergman. Paracetamol can also be combined with NSAIDs. Furthermore, the use of opioids is possible. Neuropathic pain is addressed with amitriptyline, SNRIs such as duloxetine or venlafaxine, and anticonvulsants (e.g., gabapentin, pregabalin) or opioids. If there is a central disturbance in pain regulation, anticonvulsants or antidepressants (amitriptyline, duloxetine, venlafaxine, milnacipran) should also be considered.

Source: “Management of pain,” presentation at EULAR Congress, June 11-14, 2014, Paris.

Literature:

- Andersson ML, Svensson B, Bergman S: Chronic widespread pain in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and the relation between pain and disease activity measures over the first 5 years. J Rheumatol 2013 Dec; 40(12): 1977-1985.

- Gottschalk A, Smith DS: New concepts in acute pain therapy: preemptive analgesia. Am Fam Physician 2001 May 15; 63(10): 1979-1984.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2014; 9(9): 44-45