Even if every physician comes into contact with Hodgkin’s lymphoma at the latest during his or her studies and is at least superficially familiar with the pathophysiology of this clinical picture, the eponym of Hodgkin’s disease is largely unknown. This much in advance: this is a devout Quaker who made numerous valuable contributions in a medical career that lasted only twelve years. Nevertheless, he was denied access to clinical practice. As well as the longed-for wedding.

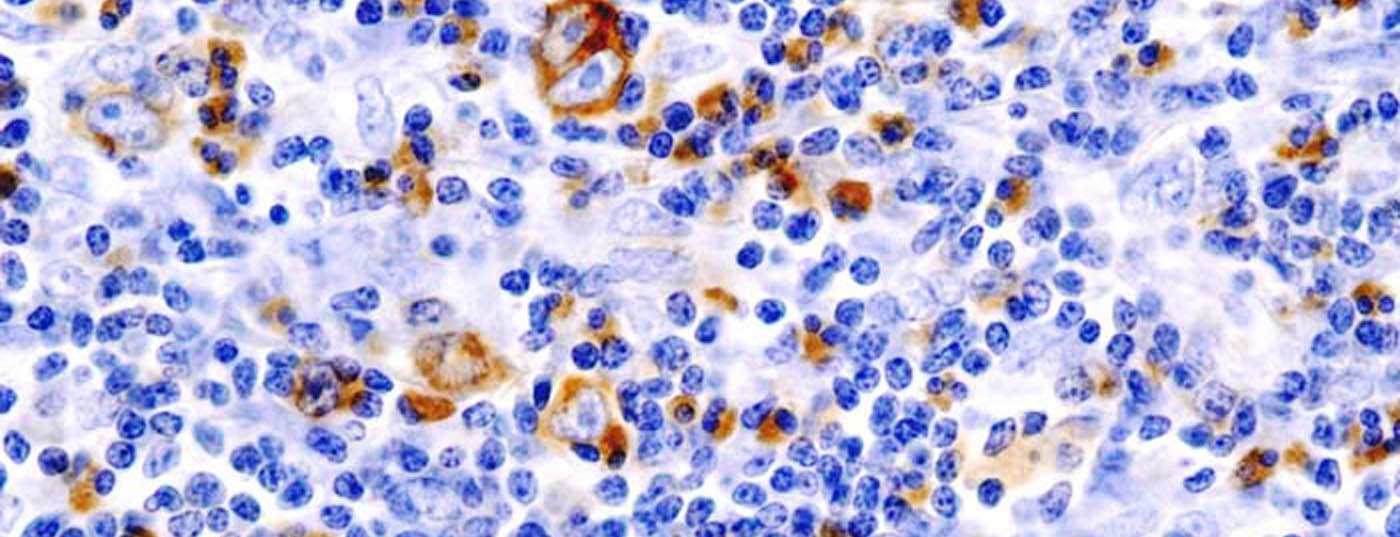

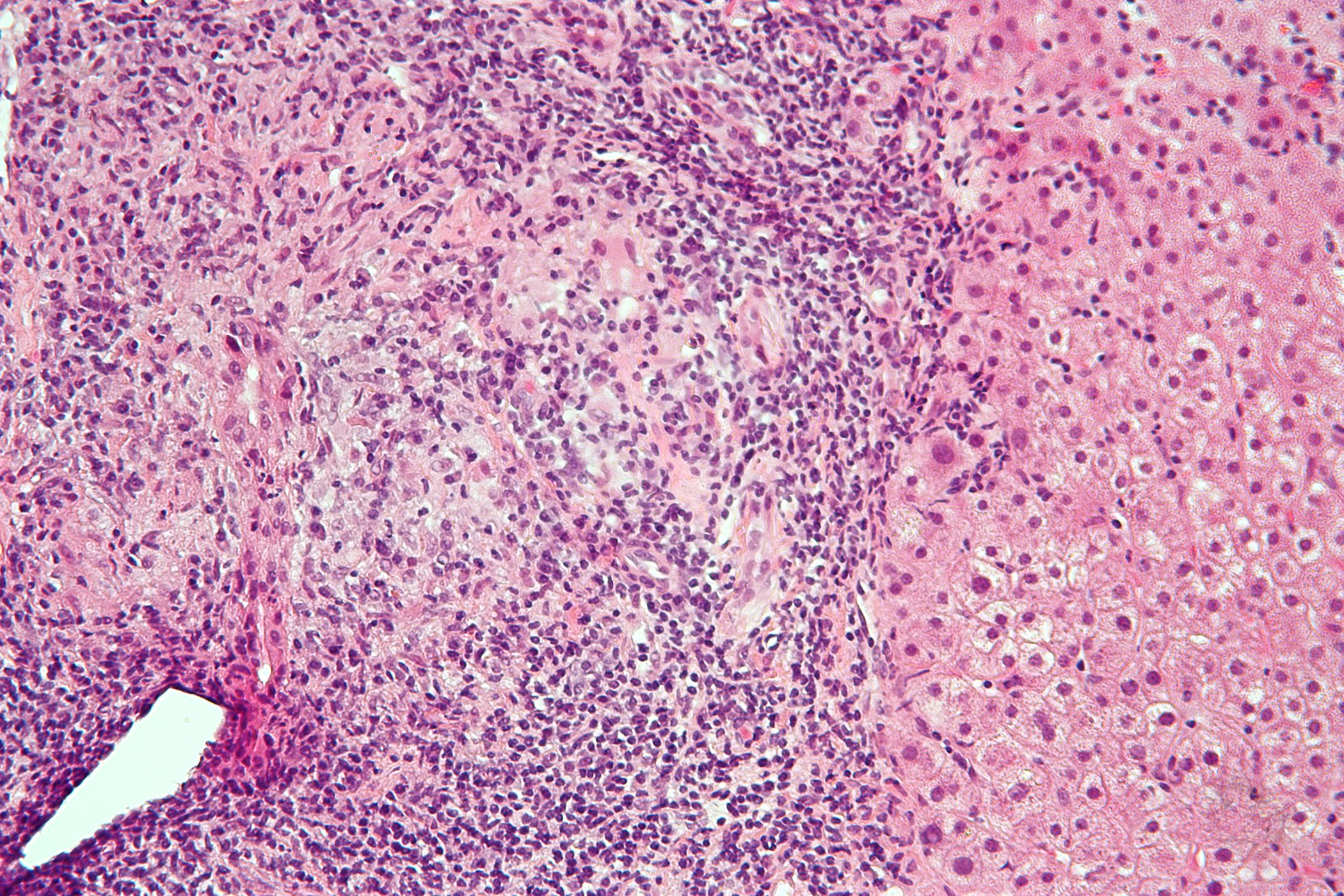

Although the disease now known as “Hodgkin’s disease” was first described by Marcello Malpighi in 1666, its namesake is different [1]. 166 years later, in January 1832, Thomas Hodgkin dealt with the clinical picture in his paper “On the morbid appearances of the Adsorbent Glands and Spleen” – and thus made his name immortal. In the course of further exploration, there were also ample opportunities for other scientists to immortalize themselves. Particular mention should be made here of Carl Sternberg and Dorothy Reed, who independently discovered the multinucleated Sternberg-Reed cells characteristic of Hodgkin’s lymphoma in 1898 [2]. Ann Arbor, nearly a hundred years later, also became a locality in medical terminology. The U.S. city in Michigan was the site of an international conference in 1971 at which the Ann Arbor classification of Hodgkin’s disease, still in use today, was developed.

Scientist and philanthropist

But back to the protagonist: Thomas Hodgkin. Who was this man who gave up his medical career in frustration at the age of 39? His story began in Pentonville, England, where Hodgkin was born into a devout Quaker family in 1798. True to his ancestry, he campaigned against humiliation and discrimination throughout his life. At the age of 21, he published an essay in which he denounced the colonization and oppression of the indigenous peoples of the Americas. In addition to social justice, the young man was also interested in science and completed an apprenticeship in a pharmacy. He then went to Edinburgh to study medicine. In 1823, the year he graduated, he already met what was probably his most important patient: Moses Montefiore, a wealthy philanthropist who was to have a decisive influence on his life.

After graduation, Hodgkin became the first lecturer in anatomy and curator of the museum at the newly opened Guy’s Hospital Medical School in London. Despite twelve productive years during which Thomas Hodgkin cataloged over 3000 specimens, published the first systematic textbook of pathology in England, and performed hundreds of autopsies, among other accomplishments, his medical career ended in 1837 when he was denied a clinical position at Guy’s Hospital. Nevertheless, Hodgkin’s research and teaching changed medical history.

For example, he brought the first stethoscope to his hospital and provided what is believed to be the second description of Hodgkin’s disease. For the first time, this malignant lymphoma was called “Hodgkin ‘s disease” in 1865 in the work of another physician who also worked at Guy’s Hospital – a name that stuck. However, fortunately, the threat of the disease changed dramatically over the years. At the time of discovery by Thomas Hodgkin, 90% of those affected died within three years of diagnosis.

Hodgkin declined admission to the prestigious Royal College of Physicians in 1836, whether on grounds of equity or, as is more often assumed, fear of not being recognized by the other members because he had not studied at Oxford or Cambridge. This decision could have been decisive for the further course of his career. For Hodgkin, contrary to his aspirations, was not given a clinical position at Guy’s Hospital. His social commitment may also have played a role in this. After all, the hospital director was a board member of the Hudson’s Bay Company, which Hodgkin sharply and repeatedly criticized for exploiting Native Americans. Whatever the cause behind Hodgkin’s rejection, it led to the termination of his medical career. In general, Hodgkin, who was not yet 40, was not fortunate at the time. Thus, in addition to a clinical position, he was also denied marriage to his great love, who was his first cousin. Such a connection was forbidden in Quaker circles in Hodgkin’s time; requests twice for an exception were not granted. In 1849 Hodgkin did marry: Sara Scaife, a widow and not a Quaker.

Nothing human was alien to him

After his medical career ended, Hodgkin’s social involvement continued. He became involved in North America, Australia, Africa, Syria and Libya, among other places – always under the protective hand of his patron Moses Montefiore, whose personal physician Hodgkin was. As diverse as the mission areas was the focus of his missions. For example, Hodgkin lectured on hygiene and advocated for the protection of child laborers and Jews. On a joint trip with Montefiore, the personal physician in Palestine finally fell ill himself with severe enteritis and died at the age of 67 on April 4 1866. The body was buried in Jaffa under the epitaph “Nothing human was foreign to him”. Just days after Hodgkin’s death, the love of his life, his cousin Sarah Godlee Rickman, also passed away.

Source: Stone MJ: Thomas Hodgkin: medical immortal and uncompromising idealist. Proceedings (Baylor University Medical Center). 2005; 18(4): 368-375.

Literature:

- Cowan DH: Vera Peters and the curability of Hodgkin disease. Current oncology. 2008; 15(5): 206-210.

- Stuart-Smith J: Reed-Sternberg cells. 2020. https://litfl.com/reed-sternberg-cells (last accessed 09/10/2021)

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2021; 9(5): 42.