Classic myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) include polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia, and primary myelofibrosis. Several sessions at the EHA Congress in mid-June addressed the revision in the guidelines, news on JAK inhibition, and the prognostic impact of driver mutations.

(ag) Ruben Mesa, MD, Arizona, spoke about the current diagnosis of polycythemia vera (PV): “This is a heterogeneous stem cell disease that is mainly associated with an increase in erythrocytes. As a consequence, thromboembolic events may occur. There is a risk of transition to myelofibrosis or acute leukemia. The revision of the WHO diagnostic criteria proposed this year [1] includes three so-called major and one minor criterion. For PV diagnosis, either all three or the first two major plus one minor criteria must be met.”

Major criteria include

- Hemoglobin levels of >16.5 g/dL (men) and

- >16 g/dL (women) or a hematocrit of > 49% (men) and > 48% (women).

- Bone marrow findings consistent with WHO criteria with pleomorphic megakaryocytes.

- Presence of a JAK2 mutation.

The minor criterion listed in the revision is subnormal serum erythropoietin level. “Thus, the diagnostic criteria for PV are under development. It is proposed to lower the threshold for hemoglobin and add hematocrit as a major criterion. Ultimately, this will lead to simplification. However, a bone marrow biopsy is required,” Mesa concluded.

“Masked” PV

The influence of bone marrow morphology as a diagnostic tool is also discussed in the revision of the WHO guidelines for so-called “masked” PV, as it allows high reproducibility of diagnosis even in cases that do not reach the previous hemoglobin and hematocrit thresholds. This is significant because overall survival in patients with “masked” PV appears to be worse than that of patients with overt PV (when the independent risk factors of age > 65 years and leukocyte count >15× 109 / l are included). Without these two risk factors, the survival rates of the two groups are comparable, which, according to the authors, indicates that some of the patients who are below the previously required thresholds of the WHO guidelines should be considered as patients with apparent PV [2,3].

Prognosis and survival in MPN

What are the mutations in primary myelofibrosis (PMF) and PV? This question was posed by Prof. Dr. med. Alessandro Vannucchi, Florence. In PV, approximately 95% of phenotypic driver mutations belong to the JAK2-V617F type and 4% to the JAK2-Exon12 type. In PMF, there are approximately 60% JAK2-V617F, 20% CALR, 8% MPL-W515, and 10% so-called “triple negative” mutations.

According to Prof. Vannucchi, prognosis in PMF is influenced by these phenotypic driver mutations in that CALR mutations show better survival outcome than JAK2, MPL, and “triple negative” mutations.

Haifa Kathrin Al-Ali, MD, Leipzig, Germany, went into more detail about prognosis and survival in MPN cases: “It is clear that myelofibrosis carries the worst survival of all MPNs: While according to a Swedish study [4] patients with essential thrombocythemia (ET) show a 17% reduced 10-year survival compared to the normal population, PV-affected patients show a 28% and PMF patients a full 81% worsened survival. To assess the risk of death and thrombosis in MPN, several prognostic tools are available, such as the so-called Lille, IPSS, DIPSS, and DIPSS-Plus scales.”

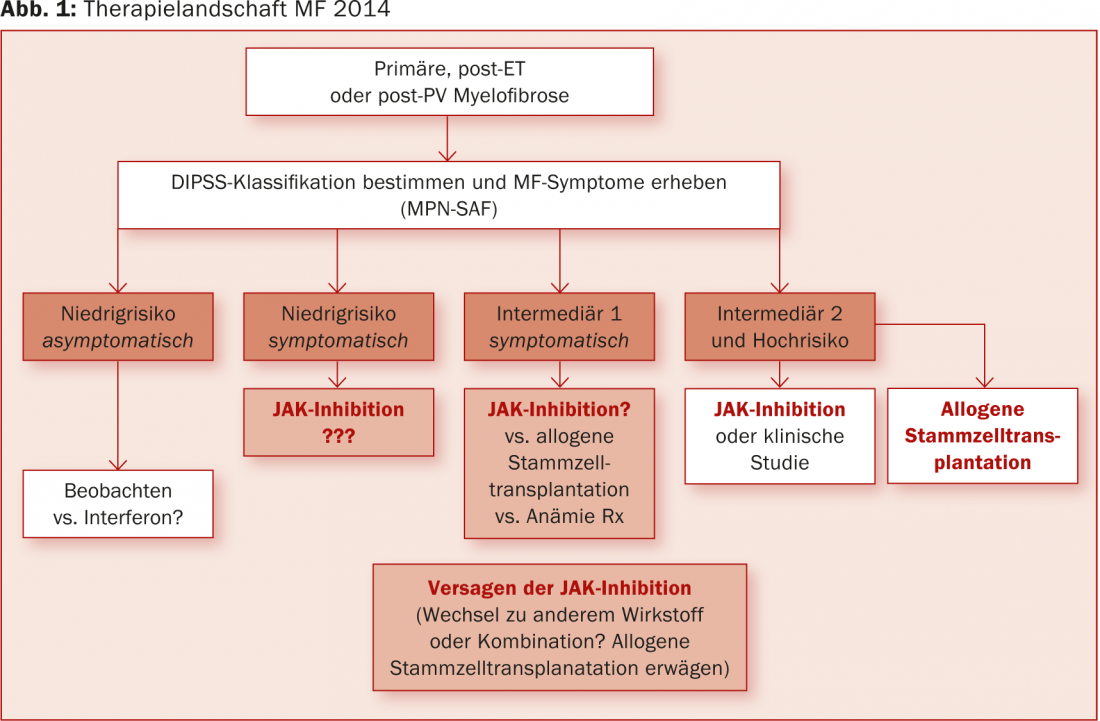

Regarding myelofibrosis, there is only one curative therapeutic option: allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. However, the outcome after transplantation depends on the initial classification on the DIPSS scale [5].

The two COMFORT trials also demonstrated that ruxolitinib improved long-term survival in MF patients (compared to placebo [6] and best available therapy [7,8]). The use of this agent for five years could delay or even reverse bone marrow fibrosis according to exploratory studies (this again compared to best available therapy) [9]. “It is possible, then, that sustained JAK1&2 inhibition modifies the disease,” Dr. Al-Ali surmised.

In PV, hydroxyurea-resistant patients are particularly affected by high mortality. Studies report a 5.6-fold higher risk of death compared to the non-resistant population. This is where new therapeutic options are urgently needed, according to Dr. Al-Ali: “The role of ruxolitinib has been tested in the RESPONSE trial. The results are encouraging with respect to the primary endpoint (control of red blood cell count and reduction of spleen volume) and also with respect to lower symptom burden compared with best available therapy [10].”

What’s next?

Claire Harrison, MD, London, described accurate diagnosis as the cornerstone of currently possible therapies for MPN: “In principle, low-dose aspirin shows good evidence only in PV, but not for PMF and ET. Nevertheless, it is also used by default in ET (except in high-risk patients). Consolidation of the study base is urgently needed here.” In addition, all reversible vascular risk factors need to be aggressively addressed. Smoking cessation is central.

“JAK inhibitors are currently fundamentally changing the therapeutic landscape of MF. A long-term survival benefit over best available therapy is emerging (3.5-year update at the 2014 EHA Congress [8]). However, we first need to carefully assess whether they can be considered as therapeutic agents in lower-risk patients in the future (Fig. 1).”

Dr. Harrison also addressed the possibility of disease modification through the use of ruxolitinib: “Among other things, a case report [11] raised eyebrows, in which complete resolution of bone marrow fibrosis was observed in an MF patient (post-PV) after three years of JAK1&2 inhibition.”

Source: EHA Congress 2014, June 12-15, 2014, Milan

Literature:

- Barbui T, et al: Rethinking the diagnostic criteria of polycythemia vera. Leukemia 2014 Jun; 28(6): 1191-1195.

- Barbui T, et al: Masked polycythemia vera diagnosed according to WHO and BCSH classification. Am J Hematol 2014 Feb; 89(2): 199-202.

- Barbui T, et al: Masked polycythemia vera (mPV): results of an international study. Am J Hematol 2014 Jan; 89(1): 52-54.

- Hultcrantz M, et al: Patterns of survival among patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms diagnosed in Sweden from 1973 to 2008: a population-based study. J Clin Oncol 2012 Aug 20; 30(24): 2995-3001.

- Scott BL, et al: The Dynamic International Prognostic Scoring System for myelofibrosis predicts outcomes after hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood 2012 Mar 15; 119(11): 2657-2664.

- Verstovsek S, et al: Long-Term Outcomes Of Ruxolitinib Therapy In Patients With Myelofibrosis: 3-Year Update From COMFORT-I. Blood 2013; 122(21): 396.

- Cervantes F, et al: Three-year efficacy, safety, and survival findings from COMFORT-II, a phase 3 study comparing ruxolitinib with best available therapy for myelofibrosis. Blood 2013 Dec 12; 122(25): 4047-4053.

- Harrison C, et al: Results from a 3.5-year update of COMFORT-II, a phase 3 study comparing ruxolitinib (rux) with best available therapy (bat) for the treatment of myelofibrosis. EHA 2014 #Abstract P403.

- Kvasnicka HM, et al: Effects Of Five-Years Of Ruxolitinib Therapy On Bone Marrow Morphology In Patients With Myelofibrosis And Comparison With Best Available Therapy. Blood 2013; 122(21): 4055.

- Vannucchi A: Ruxolitinib proves superior to best available therapy in a prospective, randomized, phase 3 study (response) in patients with polycythemia vera resistant to or intolerant of hydroxyurea. EHA 2014 #Abstract LB2436.

- Wilkins BS, et al: Resolution of bone marrow fibrosis in a patient receiving JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor treatment with ruxolitinib. Haematologica 2013 Dec; 98(12): 1872-1876.

KONRESS SPECIAL 2014; 2(5): 43-44