Most patients who present to a wound consultation have a history of suffering that goes back months. Patients usually focus on local treatment, but it is also important to clarify the cause of the ulcer. The most common etiologies are chronic venous insufficiency, peripheral arterial disease, and diabetic foot ulcer. Therapy is primarily based on the causative disease.

A chronic wound is a loss of integrity of the skin resp. Subcutaneous tissue of varying extent and depth that, despite expert treatment, does not heal within a specified time frame or at least shows a tendency to heal. The definitions of this are inconsistent [1]. In daily practice, it has proven useful to give priority to anamnestic indications and the clinical picture.

Typically, a patient will present to the wound consultation with a course of disease that can last weeks to months, sometimes years. Main symptoms are pain and dependence on treatment facilities. Institutions dedicated to the treatment of chronic wound patients are numerous. In addition to specialized outpatient clinics that specialize exclusively in wound treatment, primary care physicians, dermatologists, angiologists, phlebologists, surgeons and physicians of other specialties, not to mention non-hospital care facilities (e.g. Spitex), are also dedicated to this field. Constructive and friendly cooperation among these institutions improves the quality of treatment.

Local treatment of the chronic wound is the patient’s priority. Adequate wound treatment must also be based on the cause of the wound from the start of treatment. Apart from decubitus lesions and tumor wounds, most chronic wounds are the result of a circulatory disorder. The majority of wounds are localized to the lower extremities. Therefore, the inclusion of the vessels in the overall treatment of the wound patient is essential.

Diabetes, PAVK or venous insufficiency?

There are no recent epidemiological data on the incidence of arterial and venous ulcers in Switzerland. Two large studies from Sweden and Australia in the early 1990s found a prevalence for leg and foot ulcers in the general population of 0.11 and 0.3%, respectively [2,3]. The localization of the ulcers is dependent on the

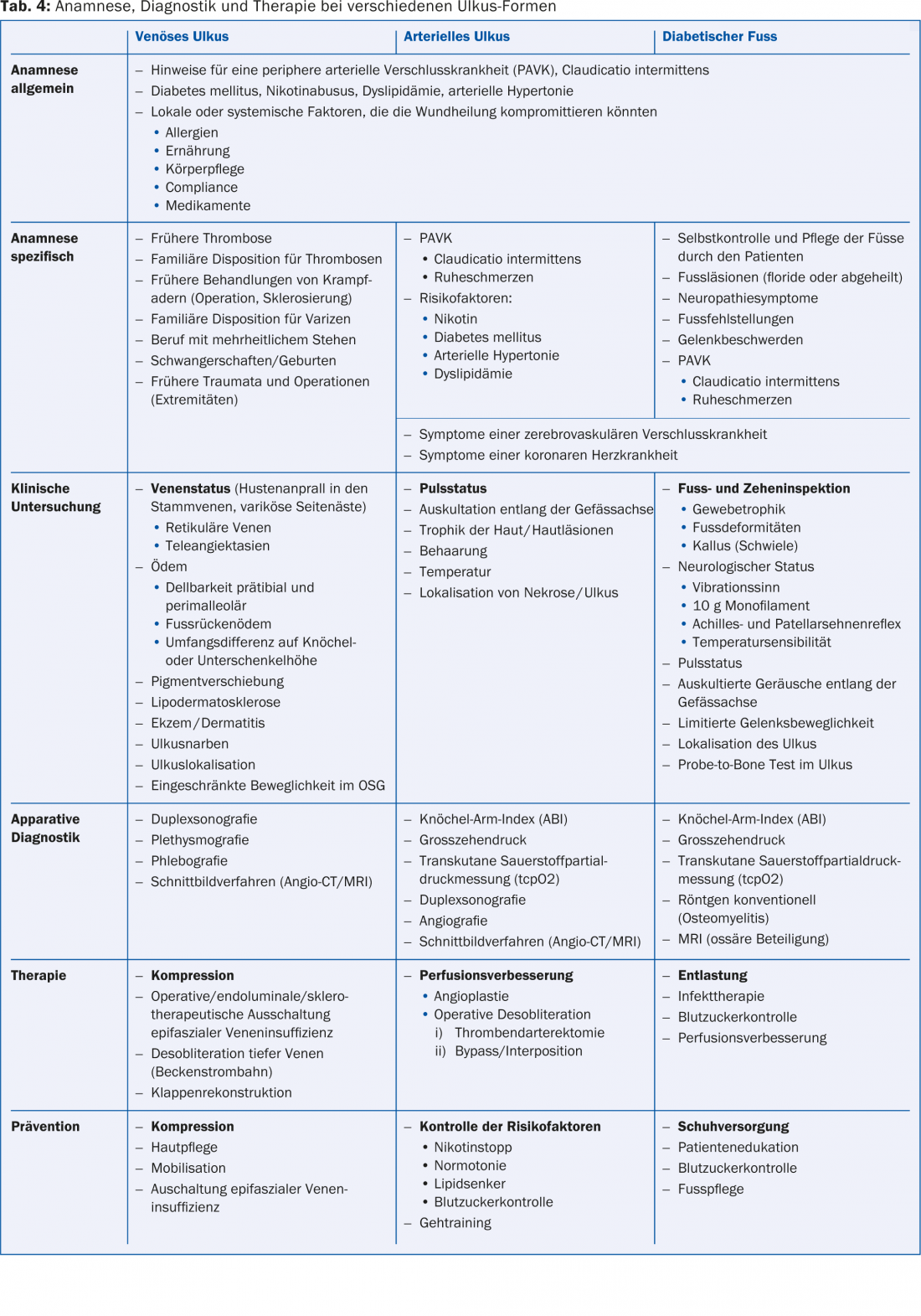

Etiology: Venous ulcers are mainly found on the lower leg and ulcerations resp. Necrosis due to peripheral arterial disease (PAVK) or diabetes mellitus predominantly on the foot. The prevalence and incidence of diabetic ulcers in Switzerland have not been studied. Studies from European countries describe a prevalence of 1.7-4.8% and an annual incidence of 0.6-2.2% [4]. History and clinical examination are the most important pillars for making a correct diagnosis.

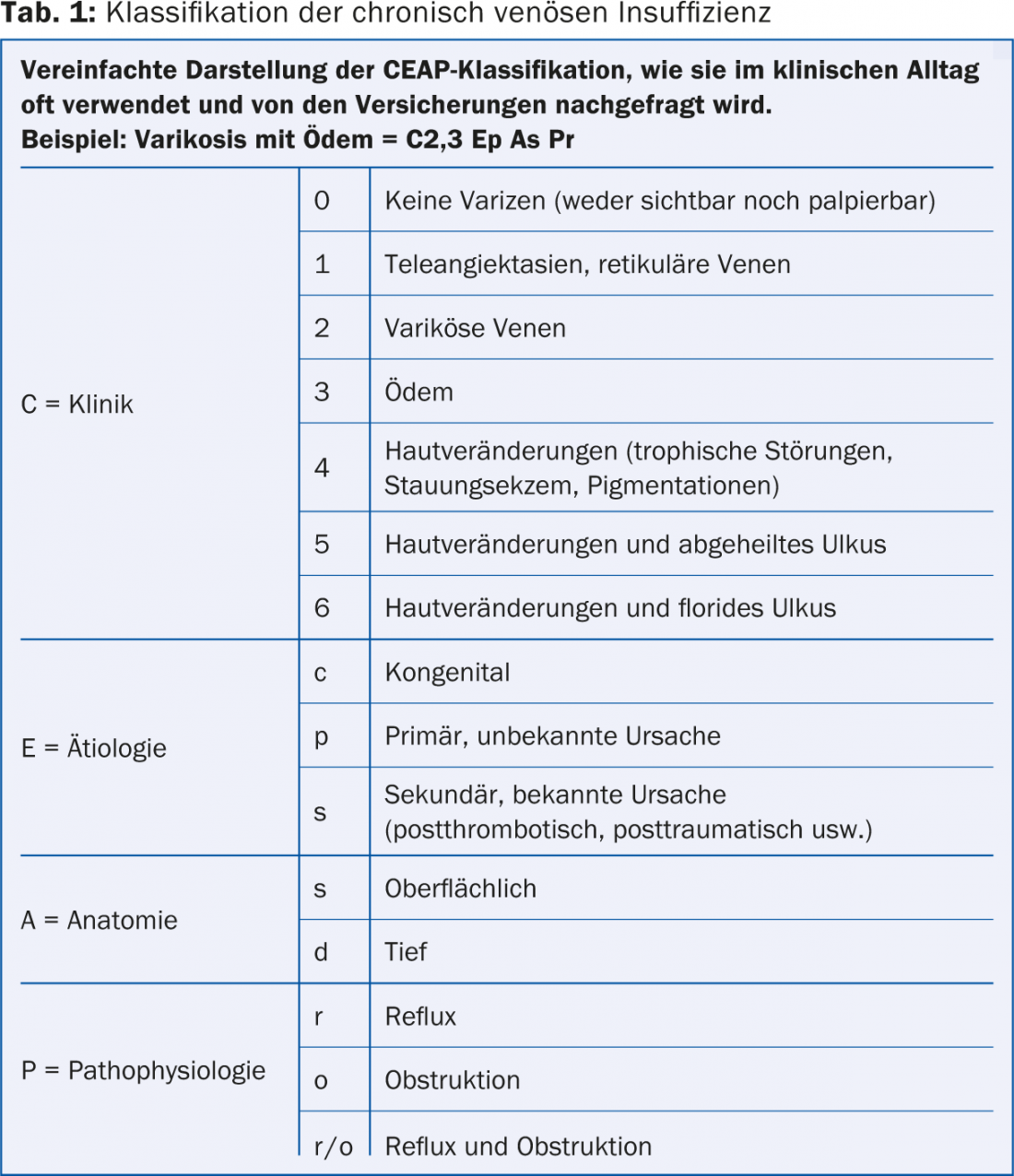

Venous ulcers develop in the context of chronic venous insufficiency, which in turn develops as a consequence of postthrombotic syndrome, varicosis, or muscle pump insufficiency [5,6]. Contrary to earlier assumptions, isolated superficial venous dysfunction may also be responsible for severe chronic venous insufficiency in addition to insufficiency of the deep venous system or combined deep and superficial venous insufficiency [7]. The CEAP classification [8] (Table 1), which was developed in 1994 within the framework of a consensus conference, allows a finer classification of venous diseases than the older classification according to Widmer (Fig. 1) [9].

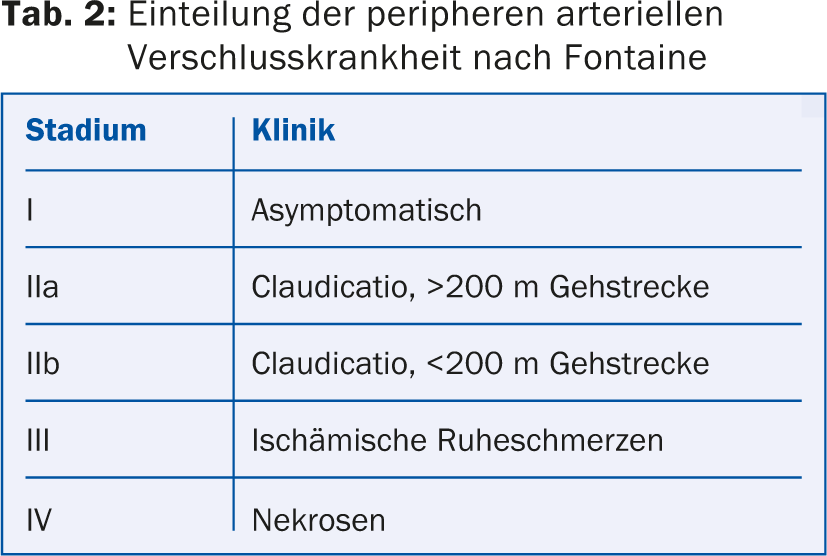

Arterial ulcers and necrosis most commonly occur in the setting of PAVD (Table 2), which is usually an arteriosclerotic disease. Smoking, diabetes mellitus, arterial hypertension, and dyslipidemia are risk factors that accelerate the onset of the disease and its progression [10]. Because patients with PAVD have increased vascular morbidity and mortality, recognizing these patients and treating risk factors is important not only for local wound healing. Stenosis and/or occlusion of an artery causes a drop in perfusion pressure distally. In mild obstruction, the signs of reduced perfusion occur only when there is an increased need for perfusion, e.g., during exercise (claudication) or during wound healing (delay). Severe obstruction already results in impaired capillary perfusion at rest, leading to rest pain and/or peripheral necrosis and potential risk of amputation [11].

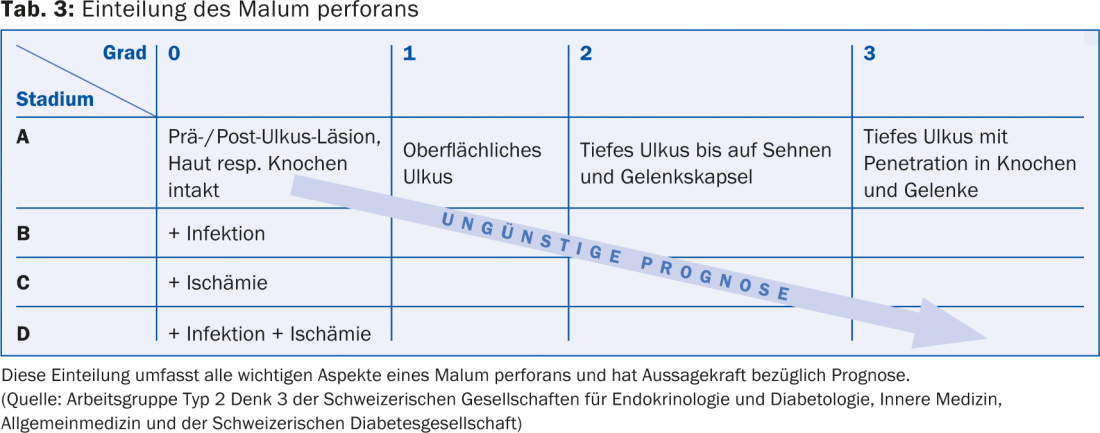

Pedal ulcers in diabetic patients (Table 3) are often classified as neuropathic, ischemic, or neuroischemic, depending on which late diabetic complication dominantly led to the ulcer. Neuropathic ulcers, the most common type, result from tissue-damaging mechanical stress on the insensitive foot. Decreased sensitivity can significantly limit the patient’s perception of touch, strain, temperature, and joint positions. PAVD predominantly affects the arteries of the lower leg and foot in diabetics. Usually, malum perforans does not develop spontaneously, but after a (chronic) trauma, which is not noticed due to the lack of pain sensation. Common causes of trauma are ill-fitting footwear, including changes in foot shape, foreign objects in footwear, inappropriate foot care, corn plasters and ointments to remove thickened calluses, injuries from barefoot walking or scalds [12] (Tab. 4).

Mobilization, compression and pressure relief

Mobilization is helpful for venous ulceration. Use of the calf muscle and joint pump and squeezing of the plantar plexus improve venous return. Under adequate compression, compromising phlebedema and venous hypertension are reduced. In patients with limited mobility in the upper ankle joint, additional physiotherapeutic treatment must be considered [13]. In contrast, gait training promotes arterial collateral formation but should only be used for secondary prevention. In diabetic lesions, which are usually caused by chronic pressure, the best possible pressure redistribution or relief is necessary and indispensable as an initial measure.

Compression with arterial involvement (mixed arterio-venous ulcers)

Often, venous leg ulcers that are maintained and complicated by, but not primarily caused by, PAVD are referred to as complicated stage (II/III). If the foot pulses are palpable, compression may be applied without restriction. If the foot pulses are not palpable, the ankle-brachial index (ABI) must be determined before any compression treatment. In general, it is recommended that compression therapy not be used if the absolute systolic ankle pressure is less than 50-80 mmHg; this also applies to an ABI less than 0.8 [14]. In the case of incompressible ankle arteries (ABI >1.3), big toe pressure measurement should be used to assess the risk of insufficient perfusion under compression therapy. These empirical values are not supported by studies. The patient must be made aware of the risks of compression treatment and asked to report to a specialist if new complaints (pain, feeling of falling asleep) or pressure points occur. Special caution is required in the case of sensory neuropathy in the context of diabetes mellitus!

Intervention/surgery to improve blood flow.

In cases of venous ulceration caused solely by insufficiency of the superficial venous system, surgical treatment of varicosis may be considered. The healing time is not significantly reduced compared to compression therapy alone, but the probability of recurrence after healing is reduced. Nonselective perforator transection is now performed endoscopically in therapy-resistant ulcers (SEPS). A paratibial fasciotomy can be performed at the same time, which is likely to promote healing of refractory ulcers [15,16]. Liberation of an obstructed or compressed iliac vein stent (May-Turner syndrome) is becoming increasingly important. Advancements in angioplasty procedures have made it possible to improve venous outflow via the obliterated iliac vein by dilatation and, if necessary, insertion of a stent.

In case of clear anamnestic and clinical indications of an arterial perfusion disorder (absent foot pulses, ABI <0.9 or >1.3 in case of mediasclerosis), direct referral to a specialist angiological-vascular surgical clarification is recommended so that the appropriate further diagnostics and therapy can be initiated as quickly as possible. Primarily, functional examinations must be performed to determine the need and urgency for therapy. Advanced diagnostics (color-coded duplex sonography, MR angiography, angio-CT, or angiography [17]) to plan therapy are then targeted according to urgency, imaging availability, and patient comorbidities.

Dilatation of stenoses and occlusions of the arterial peripheral circulation can now be performed safely with few complications. Bypass surgery of the femoropopliteal axis has accordingly become less important. In contrast, femoral thromboendarterectomy (TEA) remains a very good vascular surgical treatment option for femoral bifurcation stenosis.

CONCLUSION FOR PRACTICE

- Treatment of chronic wounds must include diagnosis and therapy of the underlying disease.

- Ulcus cruris is a finding and insufficient as a diagnosis. Only the specification enables the correct, causal treatment strategy (e.g. venous leg ulcer).

- Mobilization and compression are helpful for venous ulcers; diabetic ulcers require pressure relief.

- For surgical resp. interventional therapy, various methods are available.

Literature:

- Dissemond J: When is a wound chronic? Dermatologist 2006; 57: 55.

- Baker SR, et al: Aetiology of chronic leg ulcers. Eur J Vasc Surg 1992; 6: 245-251.

- Nelzén O, Bergqvist D, Lindhagen O: Venous and non-venous leg ulcers: clinical history and occurrence in a population study. Br J Surg 1994; 81: 182-187.

- Boulton AJM, et al: The global burden of diabetic foot disease. Lancet 2005; 366: 1719-1724.

- Eberhardt RT, Raffetto JD: Chronic venous insufficiency. Circulation 2005; 111: 2398-2409.

- Nicolaides AN: Investigation of chronic venous insufficiency, a consensus statement. Circulation 2000; 102: e126-e163.

- Tassiopoulos AK, et al: Current concepts in chronic venous ulceration. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2000; 20: 227-232.

- Beebe HG, et al: Classification and grading of chronic venous disease in the lower limbs: a consensus statement. Phlebology 1995; 10: 42-45.

- Widmer LK: Peripheral Venous disorders: Prevalence and socio-medical importance: Observations in 4529 apparently healthy person. In: Basel III Study. Hans Huber Verlag, Bern, Switzerland 1978; 1-90.

- Nogren L, et al: Inter-Society Consensus for Management of Peripheral Arterial Disease (TASC II). J Vasc Surg 2007; 45: S5-67.

- Sumner S, Zierler RE: Vascular Physiology: Essential Hemodynamic Principles. In: Vascular Surgery. Rutherford RB (ed.). Sixth Edition, Elsevier Saunders, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA; 75-97.

- Urbancic-Rovan V: Causes of diabetic foot lesions. Lancet 2005; 366: 1675-1676.

- Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario (RNAO): Nursing Best Practice Guideline: Assessment and Management of Venous Leg Ulcers. Toronto: RNAO. 2004 and Revision 2007. www.rnao.org/bestpractices.

- Gallenkemper G, et al: Guidelines for diagnosis and therapy of venous leg ulcers. Phlebol 1996; 25: 254-258.

- Hach W, Vanderpuye R: Surgical technique of paratibial fasciotomy for the treatment of chronic venous stasis syndrome in severe varicosis and postthrombotic syndrome. Med World 1985; 36: 1616-1618.

- Hauer G: The endoscopic subfascial discision of the perforating veins. VASA 1985; 14: 59-61.

- Hirsch, et al: Peripheral Arterial Disease: ACC/AHA 2005 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Peripheral Arterial Disease (Lower Extremity, Renal, Mesenteric, and Abdominal Aortic). J Am Coll Cardiol 2006; 47: 1239-1312.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2014; 24(5): 22-27