Burnout syndrome is ubiquitous in the medical world. The largest survey ever conducted on the subject raises eyebrows: Two-thirds of all young European oncologists show signs of burnout. What now?

Young oncologists from Europe answered the validated Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) and other questions about work and personal life as part of the study. The whole thing was carried out by ESMO, and the online questionnaire was also available on their website.

The MBI examines the dimensions of “emotional exhaustion,” “depersonalization,” and “reduced personal performance.” Some sample questions are shown in the overview 1.

Depersonalization” includes changes of the usual personality feeling, e.g. an altered bodily experience in the sense of “standing next to oneself” (being a stranger to oneself) or an emotional dullness when being diagnosed.

Two thirds are affected

From the total of 737 surveys from 40 European countries, the following picture emerged: Oncologists under 40 years of age (n=595).

- showed signs of burnout in 71% of cases, including 50% in the “depersonalization” subdomain (significantly more common in men), 45% “emotional exhaustion,” and 35% “reduced performance” (most common in the 26-30 age group).

- wanted psychosocial support for burnout during training in 22% of cases, but found no corresponding offers in the active hospital in 74%.

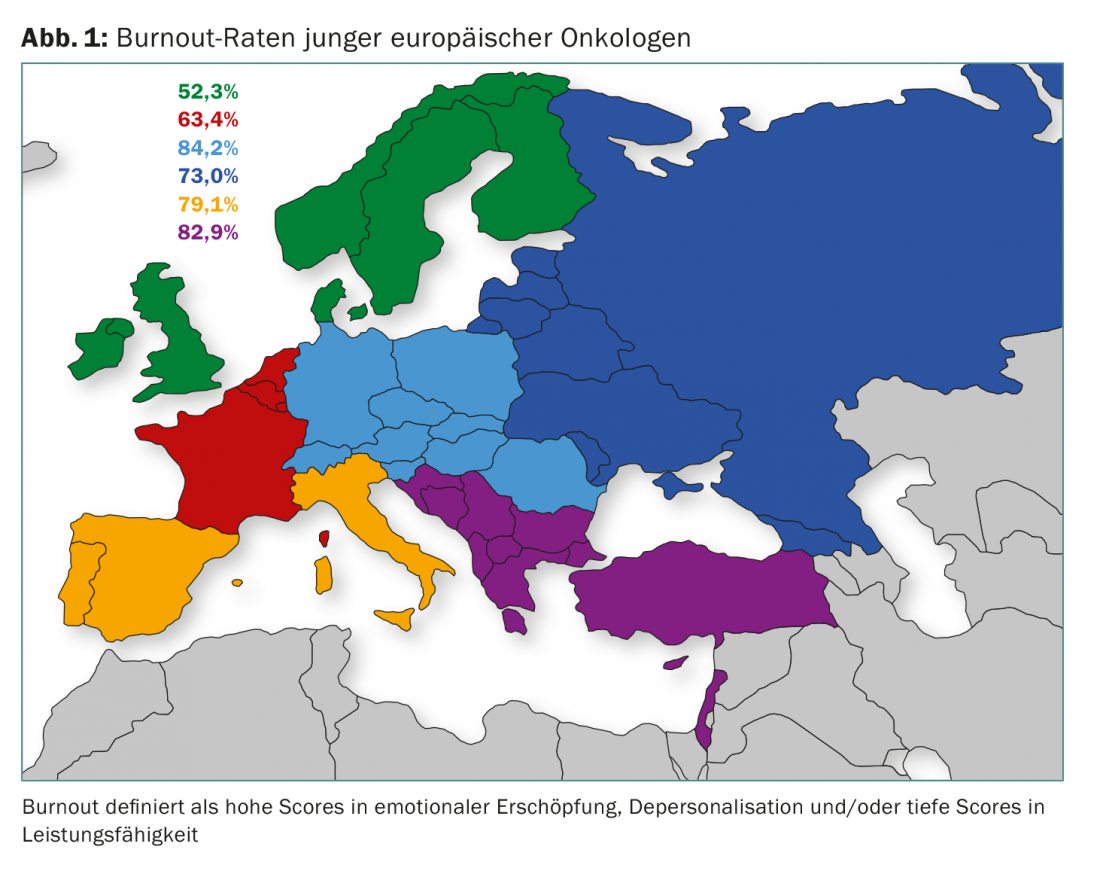

- were Central Europeans (Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Poland, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Romania, Bulgaria) in 84% of the burnout cases, burnout was rarest in Northern Europe (Scandinavia, Denmark, Great Britain, Ireland) with still 52%. In between were the Benelux and Eastern European countries and France. Spain, Italy and Southeastern Europe also scraped the upper limit. Overall, regional differences were significant.

Region, unfavorable work-life balance, lack of access to support services, living alone, and inadequate vacation time emerged as independent risk factors for burnout in multivariable analysis (p<0.05).

Possible solutions? Wrong!

The harmful consequences are clear: the burnout sufferer endangers not only himself, but also the patients being treated [1]. Burnout affects the quality of care, personal satisfaction with the medical profession, and one’s entire personal life. A first indirect step would be to provide support services at clinics for those at risk of burnout – but much more important are an appropriate work-life balance and vacation time. This could prevent the development of burnout.

Ultimately, the paradoxical question remains as to how the immense demand for medical care – especially in the field of oncology – is to be met in the future with the limited personnel resources without endangering the health of these “resources”. In addition, there are economic aspects that are increasingly pushing the medical system to its limits. Only solutions and models for society as a whole could provide a sustainable remedy. Switzerland cannot escape the question; on the contrary, it is one of the countries with the highest number of young physicians affected by burnout.

Not only Europe, but also the USA are familiar with the problem – albeit in a slightly weakened form (45% with burnout) [2]. According to an ASCO survey [3], only just one-third of oncologists are satisfied with their work-life balance – less than in any other medical specialty. Just as many said they wanted to reduce their workload in the next twelve months or even quit their job (of course, there was a connection here with dissatisfaction with the work-life balance). Some were aiming for retirement before age 65.

Now, one might think that the problem is a phenomenon of the recent past and, as a result, has yet to reach the broad consciousness of employers and politicians. This is not the case: publications have been pointing out for almost 30 years [4] that oncologists in particular represent a vulnerable professional group. Looking at the results of the new study, it seems that not too much has happened since then. Only the major oncology congresses ASCO and ESMO take their responsibility and dedicate more lectures to the topic year after year. Meanwhile, burnout rates among physicians continue to rise (while tending to decline elsewhere) [5].

In a nutshell

- Over two-thirds of young oncologists in Europe show signs of burnout.

- This puts not only themselves at risk, but also the patients.

Source: Banerjee S, et al: Professional burnout in European young oncologists: results of the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Young Oncologists Committee Burnout Survey. Ann Oncol 2017; 28(7): 1590-1596.

Literature:

- Shanafelt TD, et al: Burnout and medical errors among American surgeons. Ann Surg 2010 Jun; 251(6): 995-1000.

- Shanafelt TD, et al: Burnout and career satisfaction among US oncologists. J Clin Oncol 2014 Mar 1; 32(7): 678-686.

- Shanafelt TD, et al: Satisfaction with work-life balance and the career and retirement plans of US oncologists. J Clin Oncol 2014 Apr 10; 32(11): 1127-1135.

- Whippen DA, Canellos GP: Burnout syndrome in the practice of oncology: results of a random survey of 1,000 oncologists. J Clin Oncol 1991 Oct; 9(10): 1916-1920.

- Shanafelt TD, et al: Changes in Burnout and Satisfaction With Work-Life Balance in Physicians and the General US Working Population Between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc 2015 Dec; 90(12): 1600-1613.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2018; 6(3): 3-4.