The new oral anticoagulants (NOAKs) have long since become part of everyday clinical practice in stroke prophylaxis for atrial fibrillation. Due to their simpler, safer, and effective use, they are expected to replace vitamin K antagonist (VKA) therapy in the majority of patients. However, as with any therapy, there are some important practical aspects that must be considered for correct and safe use. Unselective use of the substances must be avoided in any case.

The large pivotal trials of the new oral anticoagulants (NOAK) for the prevention of thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation – RE-LY (dabigatran) [1], ROCKET-AF (rivaroxaban) [2], ARISTOTLE (apixaban) [3] and ENGAGE-TIMI 48 (edoxaban) [4] – have shown, that these substances are not only at least equivalent, if not superior, to vitamin K antagonists (VKA) in terms of stroke prevention, but also significantly reduce the risk of severe and/or intracranial bleeding. [5–7]. One of the biggest mistakes, however, is to view these substances indiscriminately as “one size fits all” drugs and to use them uncritically and unselectively. This article summarizes ten important aspects in daily application (building on and complementing previous work [5–9]).

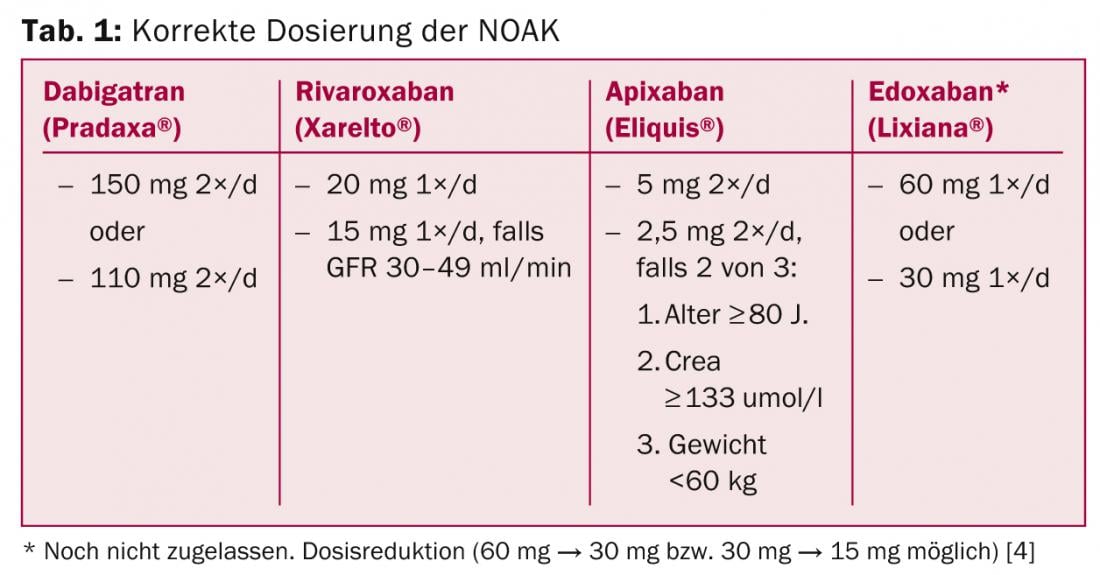

Question 1: What is the correct dosage?

Table 1 summarizes the correct dosing of NOAKs. Deviations from this are “off label” uses and should be avoided because no data are available for this (e.g., prescribing 10 mg rivaroxaban in patients with VCF and “high bleeding risk”). Initial therapy is much easier than with VKA, as full effect occurs after two to three hours – without the need for bridging with heparin or NMH.

Question 2: What to do in case of forgotten dose?

Medication compliance/adherence is critical with NOAKs, and no opportunity should be missed to remind the patient of this. Nevertheless, dosing errors naturally occur in everyday clinical practice. Based on pharmacokinetic extrapolations, it is recommended that a missed dose be made up to six hours (for 2×/d dosing, i.e., apixaban/dabigatran) or twelve hours (for 1×/d dosing, i.e., rivaroxaban) after the scheduled dose [10]. If the error is not noticed until after this time window, the dose should be skipped and the patient should proceed to the next scheduled dose.

Question 3: What to do in case of accidental double intake?

For NOAKs taken 2×/d, in case of accidental double dosing, the next scheduled dose should be skipped and the regular cycle resumed with the dose after next [10]. With 1×/d dosing, the normal cycle should be continued, since after 24 hours a large part of the substance is already eliminated again, even with accidental double dosing.

Question 4: What if the patient is not sure about the intake?

It is not uncommon for situations to arise in everyday life in which the patient is not sure whether or not he has already taken his medication. For NOAKs taken 2×/d, it is recommended not to take another dose (to avoid overdose, since the next dose is taken in 12 hours anyway). With 1×/d intake, on the other hand, it is recommended to take the potentially missed dose later, since the next intake will not occur for another 24 hours and thus there would otherwise be a longer period without relevant protection [10].

Question 5: How are NOAKs used in renal failure?

Patients with renal insufficiency represent a challenging patient population, as both thromboembolic and bleeding complications are more common [11, 12]. In severe renal insufficiency and atrial fibrillation, NOAKs have been virtually unstudied and, accordingly, should not be used (although some are approved in this setting as well) [13]. The problem is finding a good alternative – because VKA are also formally contraindicated in severely impaired renal function. Indeed, it has been shown that the benefit of VKA decreases with increasingly impaired renal function [14]. Nevertheless, VKA currently appear to be the best option in patients with atrial fibrillation and severe renal insufficiency, taking into account the caveats mentioned above. Here, optimal INR setting is more crucial than ever.

The dosage of apixaban (50% renal clearance of absorbed substance) and rivaroxaban (37% renal clearance) is reduced in moderately impaired renal function (GFR 50 – 30 ml/min) (Table 1). Both agents have been shown to be effective and safe in this patient population (compared with VKA), with a very good safety profile demonstrated for apixaban in particular compared with VKA [11, 15]. Especially in the presence of other risk factors for bleeding (such as age ≥ 80 years, HAS-BLED score ≥ 3), it is recommended to reduce the dose of dabigatran (80% renal clearance) to 2 × 110 mg/d starting at a GFR <50 ml/min [13]. In principle, the use of dabigatran in patients with a GFR <40 ml/min should be well considered, as experience has shown that in these patients a further deterioration of renal function with corresponding accumulation of the substance can occur rapidly, for example in the context of intercurrent diseases, co-medication (NSAIDs!), or dehydration.

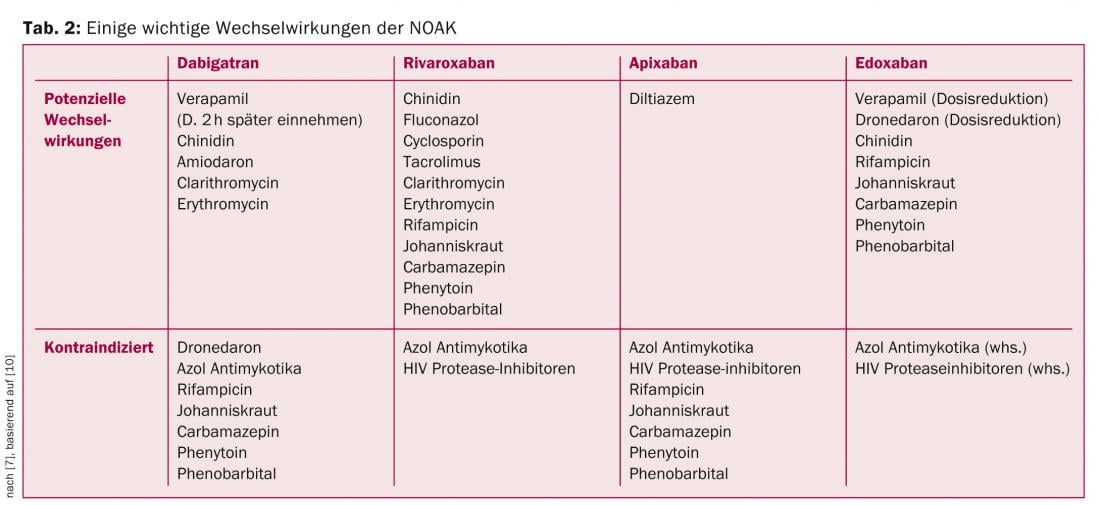

Question 6: Do interactions with other medications exist?

Although NOAKs have a much lower potential for drug-drug interactions than VKA, there are some important interactions to consider. Some of the most important interactions are summarized in Table 2, based on the recommendations of the EHRA [10].

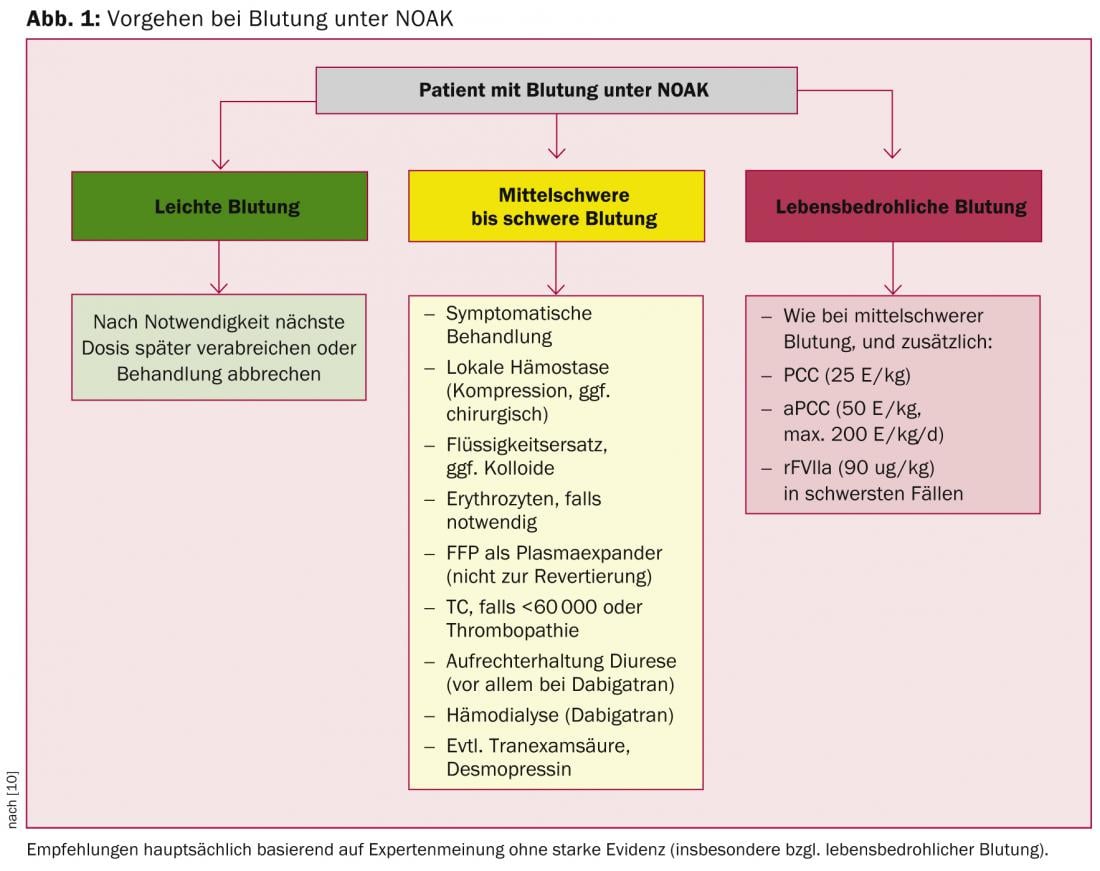

Question 7: What is the procedure for bleeding under NOAKs?

Bleeding complications, particularly intracranial and life-threatening bleeding, occur significantly less frequently with NOAKs than with VKAs.

Specific rapid-acting antidotes are under development for NOAKs; however, it will most likely be several years before they are introduced into clinical practice. Accordingly, unsepcific procoagulants such as PCC, aPCC, or recombinant FVIIa must be resorted to for rapid antagonization. This situation is not entirely dissimilar to that with VKA, since here, too, “specific” antagonization by means of vitamin K is anything but rapidly effective in the emergency situation. In principle, antagonizing anticoagulation – whether by VKA or NOAK – is not without risks, since it induces a procoagulant state. Thus, even normalization of coagulation parameters does not necessarily correlate with improved clinical outcome, especially after intracranial hemorrhage [16–18]. The EHRA recommendations, which are based primarily on preclinical data and pharmacokinetic extrapolations, take this into account (Fig. 1) [10]. Accordingly, the use of procoagulants is recommended only in cases of severe and life-threatening bleeding, whereas general measures are primarily used in cases of mild and moderate bleeding.

Question 8: What is the best course of action for “triple anticoagulation”?

Patients with AF who formally require dual antiplatelet therapy (so-called “triple anticoagulation”) in addition to plasmatic anticoagulation (NOAK/VKA) because of ACS and/or stent implantation are at greatly increased risk for major bleeding [19]. Currently, apart from a few patients from the RE-LY trial, there are no data on the use of NOAKs in combination with aspirin and clopidogrel. Similarly, no data are available on the combination of NOAKs with the new-generation ADP receptor antagonists prasugrel and ticagrelor. Therefore, a combination of these substances must be discouraged at the present time. It is anticipated that the recommendations will be further adjusted as new data emerge, both regarding the latest generation stents and regarding the combination of NOAKs as well as the new antiplatelet agents. At present, however, the approach proposed in the ESC guidelines using ASA, clopidogrel, and VKA appears to be the best alternative (Table 3) [20]. In the recently published WOEST study, the combination of clopidogrel and VKA was shown to be superior to classical “triple anticoagulation” – both in terms of bleeding events and ischemic endpoints [21]. In daily practice, the duration of “triple anticoagulation” originally recommended in the ESC guidelines is therefore already significantly reduced, depending on the clinical setting.

Question 9: Can NOAKs be used in cardioversion?

The best data regarding cardioversion under NOAK are available for dabigatran (from the RE-LY trial): Here, the latter was equally effective as VKA with respect to stroke and bleeding [22]. For rivaroxaban and apixaban, the patient numbers published to date are smaller but point in the same direction. The decisive factor in everyday life is compliance! If it can be assured that the patient has taken the NOAK regularly for the preceding three (preferably four to five) weeks, cardioversion under NOAK appears to be safely feasible [10]. Otherwise, a thrombus must be excluded by TEE. Ongoing studies and registries will provide further data on the optimal procedure.

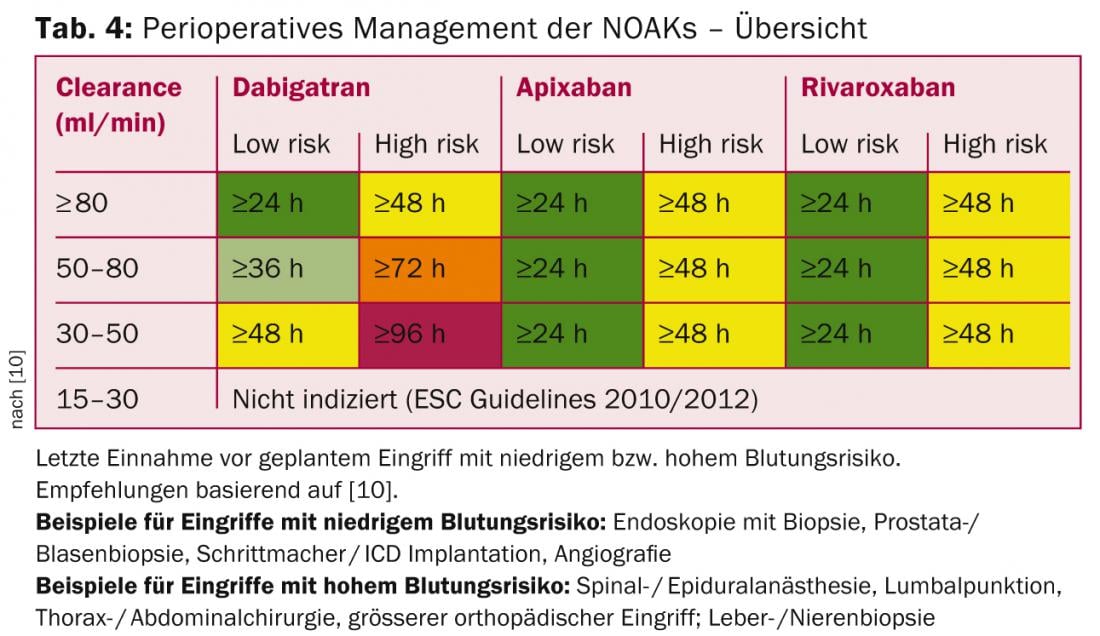

Question 10: How does perioperative management work?

Due to the pharmacokinetics of NOAKs, bridging is not necessary perioperatively (which is also increasingly less common for VKA). The recommendation to discontinue NOAK is based on the bleeding risk of the procedure as well as renal function (greatest impact with dabigatran; Tab. 4).

For procedures with very low bleeding risk (dental interventions, cataract, glaucoma, endoscopy without intervention), the procedure can usually be performed at the trough level of NOAK (i.e., before planned next dose), with intake of the next dose six hours later (if hemostasis is good) [10].

Following the procedure, NOAK can be restarted as early as six to eight hours in the case of direct or complete hemostasis. For major procedures with a residual risk of bleeding, it may be necessary to wait two to three days before restarting. In these situations, unfractionated or low-molecular-weight heparin should be started at prophylactic doses six to eight hours postintervention. After safe hemostasis, the switch to full-dose NOAK is made.

Summary

Due to the convincing study results and their ease of use, NOAKs have long since become part of everyday clinical practice in the prevention of stroke in atrial fibrillation. For many of the above recommendations for practical application, no data from randomized trials are available. Nevertheless, they do occur in everyday life, so recommendations on the best possible behavior in these situations are needed, based on expert opinions such as the detailed “Practical Guide” of the EHRA [10]. For a more detailed study, the reader is referred to this and other further literature [6, 7, 10].

PD Jan Steffel, MD

Conflict of interest statements: PD Jan Steffel, MD, has received consulting and/or lecture fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer HealthCare, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, Pfizer and Roche.

Literature:

- Connolly SJ, et al: Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2009; 361: 1139-1151.

- Patel MR, et al: Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2011; 365: 883-891.

- Granger CB, et al: Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2011; 365: 981-992.

- Giugliano RP, et al: Edoxaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2013.

- Steffel J, Braunwald E: Novel oral anticoagulants: Focus on stroke prevention and treatment of venous thrombo-embolism. Eur Heart J 2011; 32: 1968-1976.

- Steffel J, Brunckhorst C: Stroke prophylaxis in atrial fibrillation. Bremen, Germany: UniMed; 2012.

- Steffel J, et al: Stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. Bremen: UniMed; 2014 (in press).

- Steffel J: New anticoagulants: prevention and treatment of thromboembolic events. Leading Opinions Cardiology + Vascular Medicine 2011; 2: 14-19.

- Steffel J: The new anticoagulants – practical aspects in application. Leading Opinions Cardiology + Vascular Medicine 2012; 2: 10-14.

- Heidbuchel H, et al: European heart rhythm association practical guide on the use of new oral anticoagulants in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. Europace 2013; 15: 625-651.

- Steffel J, Hindricks G: Apixaban in renal insufficiency: successful navigation between the scylla and charybdis. Eur Heart J 2012; 33: 2766-2768.

- Steffel J: New oral anticoagulants in impaired renal function and dialysis. Leading Opinions Nephrology 2013; 2: 73-75.

- Camm AJ, et al: 2012 focused update of the esc guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: An update of the 2010 esc guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. Developed with the special contribution of the european heart rhythm association. Europace 2012.

- Marinigh R, Lane DA, Lip GY: Severe renal impairment and stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: implications for thromboprophylaxis and bleeding risk. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 57: 1339-1348.

- Hohnloser SH, et al: Efficacy of apixaban when compared with warfarin in relation to renal function in patients with atrial fibrillation: Insights from the aristotle trial. Eur Heart J 2012.

- Dowlatshahi D, et al: Poor prognosis in warfarin-associated intracranial hemorrhage despite anticoagulation reversal. Stroke 2012; 43: 1812-1817.

- Lee SB, et al: Progression of warfarin-associated intracerebral hemorrhage after inr normalization with ffp. Neurology 2006; 67: 1272-1274.

- Kuwashiro T, et al: Effect of prothrombin complex concentrate on hematoma enlargement and clinical outcome in patients with anticoagulant-associated intracerebral hemorrhage. Cerebrovasc Dis 2011; 31: 170-176.

- Sourgounis A, et al: Coronary stents and chronic antico-agulation. Circulation 2009; 119: 1682-1688.

- Camm AJ, et al: Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: The task force for the management of atrial fibrillation of the european society of cardiology (esc). Europace 2010; 12: 1360-1420.

- Dewilde WJ, et al: Use of clopidogrel with or without aspirin in patients taking oral anticoagulant therapy and undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: An open-label, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet 2013; 381: 1107-1115.

- Nagarakanti R, et al: Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: An analysis of patients undergoing cardioversion. Circulation 2011; 123: 131-136.

CARDIOVASC 2014; 13(2): 12-16

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2014; 9(6): 32-37