Atrial fibrillation is the most common sustained cardiac arrhythmia, occurring in 1-2% of the population and increasing up to 15% with age. However, especially in elderly and very old patients with atrial fibrillation, effective stroke prophylaxis using oral anticoagulants is often not performed because of concerns about increased bleeding complications. Which risk weighs more heavily?

Practitioners with older patients always face significant challenges. Because not only is atrial fibrillation common, the lifetime risk of stroke increases [1,2]. In addition, there is an increased risk of venous thromboembolism by up to 28 times, associated with a significantly increased risk of major bleeding under anticoagulation [3–6]. In fact, anticoagulants are one of the greatest risk factors for adverse drug-associated events in elderly patients [7]. However, one in four ischemic strokes in the elderly is due to cardioembolism due to atrial fibrillation [8]. So what is to be done?

Clinical concerns prevent effective prophylaxis

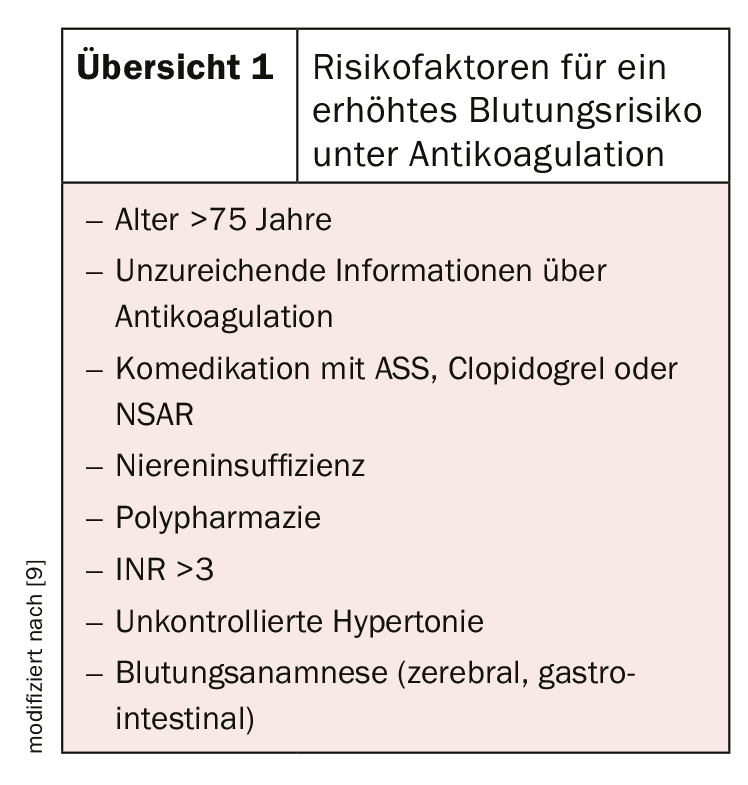

There are a number of good reasons why stroke prophylaxis should be used with caution in an elderly clientele. These include often impaired cognition, increased risk of falls, difficulties in INR setting, nutritional status, comedications, and possible comorbidities. This is because the risk of bleeding increases, for example, in patients older than 75 years, comedication with ASA, clopidogrel, or NSAIDs, or renal insufficiency (review 1) [9]. However, studies have shown that the benefit of oral anticoagulation is far greater than the risk of bleeding, even in elderly and very elderly patients [10].

Oral anticoagulation also useful in elderly patients

In addition to vitamin K antagonists (e.g., phenprocumom, warfarin, acenocumarol), direct factor Xa antagonists (e.g., rivaroxaban, apixaban, edoxaban) and direct thrombin antagonists (e.g., dabigatran) are available for oral anticoagulation. DOAKs in particular have gained in importance in recent years. They demonstrate superior efficacy (through fewer hemorrhagic strokes and reduction in mortality) and safety (through less intracranial hemorrhage) in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation compared with vitamin K antagonists [11]. Consistent effects were also observed in elderly patients [12].

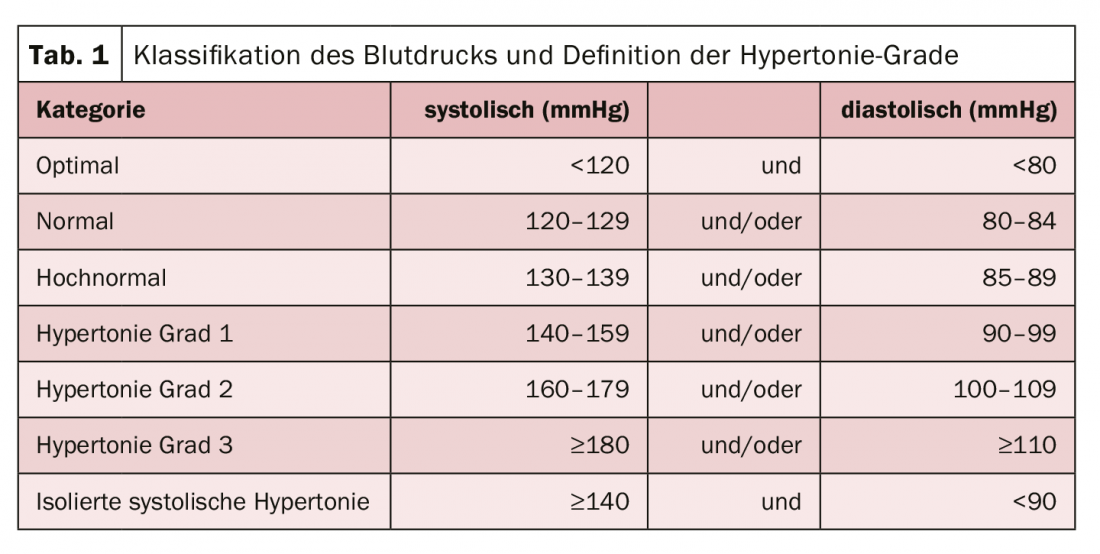

Despite all the advantages, a few aspects should nevertheless be taken into account in practice (tab. 1) . These include dose adjustments or the higher rate of gastrointestinal bleeding. Therefore, renal function should always be assessed by creatinine clearance prior to initiation of therapy with DOAC. During treatment, it should also be monitored regularly. Discontinuation of anticoagulation should be considered when life expectancy is very short, advanced tumor disease, severe dementia, very high bleeding risk, poor functional status/dependence on care, poor compliance, or alcohol abuse.

Literature:

- Ng KH, et al: Cardiol Ther. 2013; 2(2): 135.

- Wolf PA, et al: Stroke 1991; 22(8): 983.

- Stein PD, et al: Arch Int Med 2004; 164(20): 2260.

- Pautas E, et al Drugs Againg. 2006; 23(1): 13-25.

- Pengo V, et al: Thromb Haemost. 2001; 85/3): 418.

- Hajjar ER, et al: Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2003; 1(2): 82.

- Nieuwlaat R, et al: Eur Heart J. 2006; 27(24): 3018.

- Gladstone DJ, et al: Stroke 2009; 40: 235-240.

- Kagansky N, et al: Arch Intern Med. 2004; 164(18): 2044.

- Patti, et al: J Am Heart Assoc. 2017,6: e005657.

- Ruff, et al: Lancet. 2014; 383: 955-962.

- Saldon AH, Tsakiris DA: Swiss Med Wkly 2016; 146: w14246.

- Granziera, et al: JAMDA 2015; 16: 358-364.

CARDIOVASC 2020; 18(3): 24