While early stages are often asymptomatic, various complications can occur in the setting of decompensated cirrhosis. Hepatic encephalopathy is one of them.

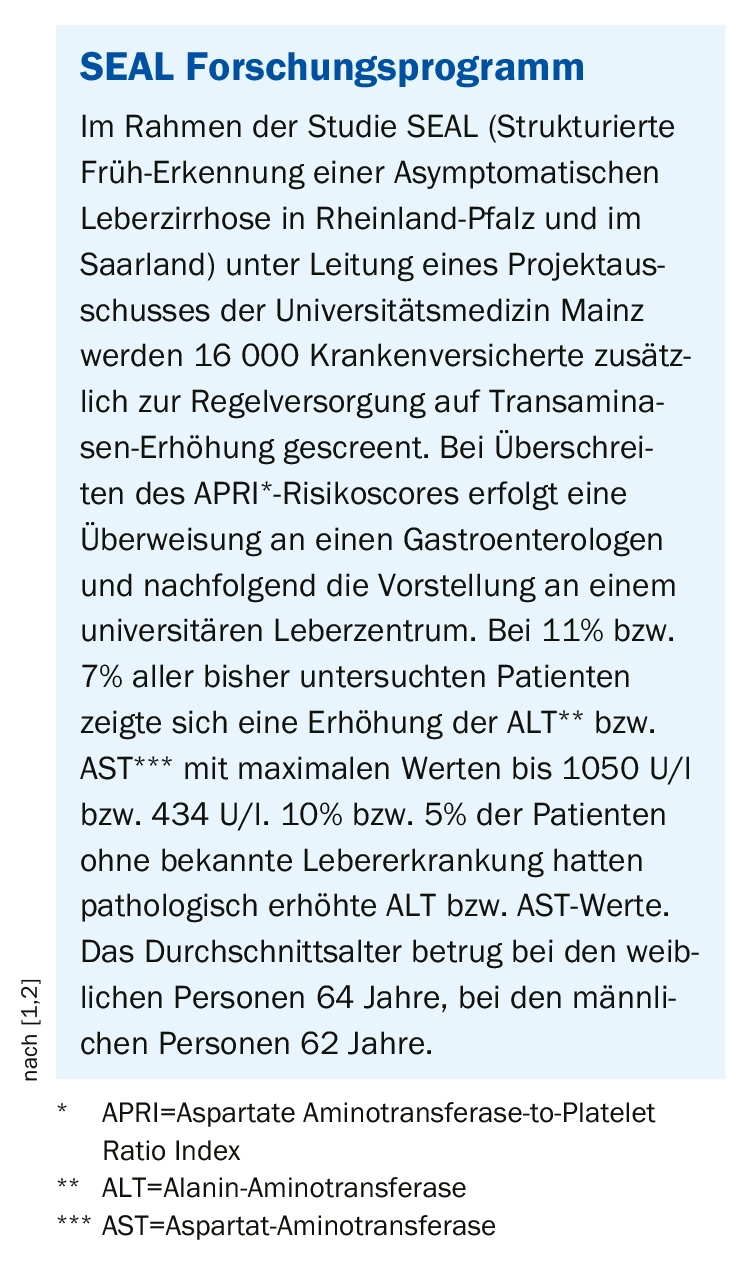

The determination of liver values should be integrated into medical check-up examinations in risk groups, according to Univ. Prof. Dr. Peter Galle, University Medical Center Mainz. “Abnormal results must be further clarified with ultrasound examination,” says the expert [1]. Screening for elevation of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) in combination with non-invasive fibrosis risk tool could be suitable to increase the early diagnosis rate of treatable liver diseases, according to Prof. Galle, member of the project management of the SEAL study (Box).

Decompensated liver cirrhosis carries risks of complications

Liver cirrhosis refers to severe liver parenchymal damage, which can be induced by various factors (e.g., necrosis, inflammation, fibrogenesis) [3]. Characteristic histologic features include parenchymal loss, nodularity, and vascular architectural disruption [3]. It is the end stage of a chronic liver process that progresses over years to decades. The most common underlying conditions include alcoholic and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (AFLD/NAFLD) and viral hepatitides (hepatitis B and C). Liver cirrhosis is also common in the presence of certain storage diseases (hemochromatosis, α1-antitrypsin deficiency, Wilson’s disease) and autoimmune diseases. The annual incidence of cirrhosis-related deaths worldwide is >1 million [4]. There is an emerging trend in prevalence, which is related to the increase in NAFLD [5]. NAFLD used to be considered the end-stage of chronic liver disease, but it is now thought that reversibility is possible in certain cases [6,7]. Clinical manifestations often occur only in the decompensation stage; the compensated phase is often asymptomatic. Because liver cirrhosis is a multisystem disease, morbidity and mortality are associated with complications resulting from portal hypertension (e.g., varices, ascites, splenomegaly, hepatic encephalopathy, immune dysfunction). Infections and gastrointestinal bleeding are the most common causes of hospitalization, decompensation, liver failure, and failure of other organs (“acute-on-chronic” liver failure, ACLF) [8]. This is associated with high mortality. Another complication with high mortality is hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). It is therefore important to diagnose liver disease at an early stage and to treat it as best as possible, to recognize liver cirrhosis and any complications and to treat them symptomatically.

Hepatic encephalopathy: indicator for progression of liver cirrhosis

A large proportion of those affected by chronic liver disease develop minimal hepatic encephalopathy. This can develop into manifest hepatic encephalopathy, a condition also associated with a high mortality rate. An analysis by Cordoba et al. [9] using data from 1348 cirrhotic patients hospitalized for decompensation reached the following conclusions:

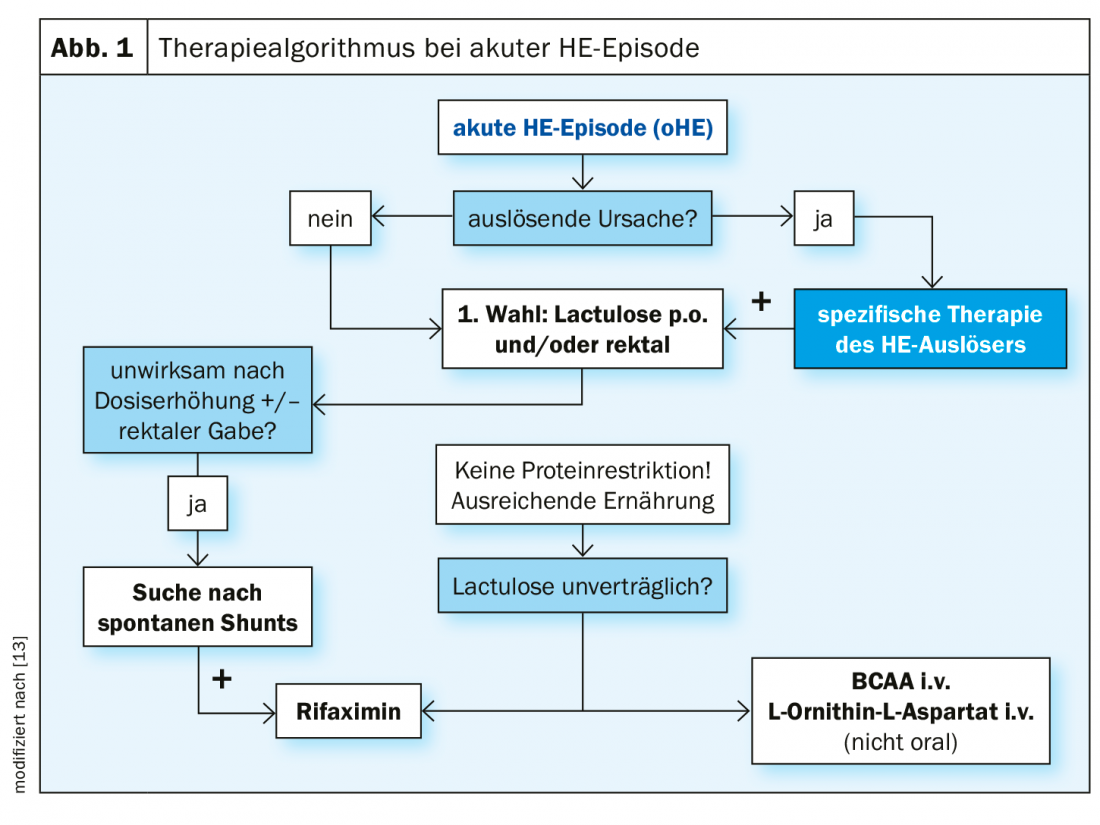

A history of hepatic encephalopathy is a risk factor for recurrence of this complication. The prognosis of hepatic encephalopathy with ACLF is very poor compared with hepatic encephalopathy without ACLF. Hepatic encephalopathy without ACLF is common in elderly cirrhotic patients, abstinent alcoholics, absence of severe liver failure, among others. Hepatic encephalopathy with ACLF is common in younger cirrhotic patients, active consuming alcoholics, severe liver failure. Independent risk factors for mortality were age, bilirubin, INR, creatinine, sodium, and severity of hepatic encephalopathy. Minimal hepatic encephalopathy is an early indicator of further progression of liver cirrhosis, explained PD Tobias Müller, MD, Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin [10,11]. Pathogenetically, increased ingestion of ammonia by degradation of endogenous and/or intestinal proteins leads to dysfunction and swelling of brain astrocytes. Hepatic encephalopathy worsens the prognosis of affected individuals. The “West Haven Criteria” can be used to classify this neuropsychiatric complication (Table 1) [10]. Intensive care is indicated for severity 3 and 4. Treatment of an acute episode of hepatic encephalopathy is primarily with lactulose, as is secondary prophylaxis (Fig. 1) . In case of intolerance or ineffectiveness of non-absorbable disaccharides, rifaximin alone or in combination with lactulose can be switched to.

Literature:

- Galle PR: Management of liver diseases – State of the art. Slide presentation Univ.-Prof. Dr. Peter R. Galle, University Medicine Mainz (D), Industry Symposium, DGIM May 6, 2019.

- Nagel M, et al: Liver screening program SEAL: Screening of the general population for structured early detection of liver fibrosis and cirrhosis. Z Gastroenterol 2019; 57(09): e246.

- Tsochatzis EA, Bosch J, Burroughs AK: Liver cirrhosis. Lancet Lond Engl 2014; 383: 1749-1761.

- Mokdad AA, et al: Liver cirrhosis mortality in 187 countries between 1980 and 2010: a systematic analysis. BMC Med 2014; 12: 145.

- Goosens M: Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: stop trivializing it! Swiss Med Forum 2018; 18(1-2): 10-12.

- Marcellin P, et al: Regression of cirrhosis during treatment with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for chronic hepatitis B: a 5-year open-label follow-up study. Lancet Lond Engl 2013; 381: 468-475.

- Lee YA, Wallace MC, Friedman SL: Pathobiology of liver fibrosis: a translational success story. Gut 2015; 64: 830-841.

- Gustot T, Moreau R: Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure vs. Traditional Acute Decompensation of Cirrhosis. J Hepatol 2018. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2018.08.024.

- Cordoba J, et al: Characteristics, risk factors, and mortality of cirrhotic patients hospitalized for hepatic encephalopathy with and without acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF). J Hepatol 2014; 60(2): 275-281.

- Müller T: Management of liver diseases – State of the art. Slide presentation PD Dr. med. Tobias Müller, Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin (D). Industry Symposium, DGIM May 6, 2019.

- Ampuero J: Minimal hepatic encephalopathy identifies patients at risk of faster cirrhosis progression. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2018; 33(3): 718-725.

- Conn H.O.. Hepatic encephalopathy. In: Schiff L, Schiff ER, Eds. Diseases of the Liver. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Lippicott 1993, pp. 1036-1060.

- Gerbes AL, et al: Update of the S2k guideline of the German Society of Gastroenterology, Digestive and Metabolic Diseases (DGVS) “Complications of liver cirrhosis”. AWMF no: 021-017 version November 2018, www.awmf.org

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2019; 14(12): 30-31