Neuroendocrine neoplasms are usually sporadic and often originate in the gastroenteropancreatic space. They are usually diagnosed incidentally, as they are often non-functional. Therefore, in most cases it is an already advanced, often metastasized tumor disease.

The term “neuroendocrine” refers to cells with histological characteristics of glandular tissue that are usually diffusely present in various organs of the body and can secrete hormones. Depending on the function and localization, amines (for example, catecholamines) or peptides (for example, somatostatin) are produced by which the activity of the surrounding tissue is regulated. Embryologically, they were long considered to be part of the neural crest, but have since been assigned to the endoderm, just like exocrine cells of the gastrointestinal tract. Historically, these cells have been grouped into a diffuse neuroendocrine system (formerly also called APUD (“amine precursor uptake and decarboxylation”)). However, since these terms are of no relevant histopathologic or clinical significance, they should no longer be used.

If these cells degenerate, they are referred to as neuroendocrine neoplasms (NEN). This umbrella term encompasses both the slowly proliferating neuroendocrine tumors (NET) and carcinoids of the lung, as well as the much more aggressive and prognostically unfavorable neuroendocrine carcinomas (NEC). All recommendations in this article will thus be based on this classification.

Neuroendocrine neoplasms occur mostly sporadically, with an estimated incidence of about 5/100,000 population. Familial clustering can be observed in multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) I and II and in rare diseases such as von Hippel-Lindau syndrome or neurofibromatosis type 1 (Recklinghausen). Most NEN originate from the gastroenteropancreatic space (GEP-NEN), with approximately 25-30% originating from the lung [1].

Symptomatology

Although hormone production is a typical feature of neuroendocrine neoplasms, so-called functional tumors-that is, tumors whose hormone production and secretion result in symptoms-are rare. The complaints caused by functional tumors depend on the respective secretion of bioactive substances. For example, insulinomas or gastrinomas, which represent the majority of these functional NENs, lead to severe, potentially life-threatening hypoglycemia or multiple gastric ulcerations (Zollinger-Ellison syndrome). Another typical clinical picture is carcinoid syndrome, in which excessive serotonin secretion can lead to severe watery diarrhea, flushing symptomatology, and bronchospasm. Endocardial fibrosis may occur as a late complication, leading to heart failure with fatal outcome (Hedinger syndrome).

However, up to 90% of all NENs are nonfunctional and are diagnosed either as incidental findings or in the context of nonspecific complaints. In most cases, because of the indolent course, it is an advanced, already metastasized tumor disease.

Diagnostics

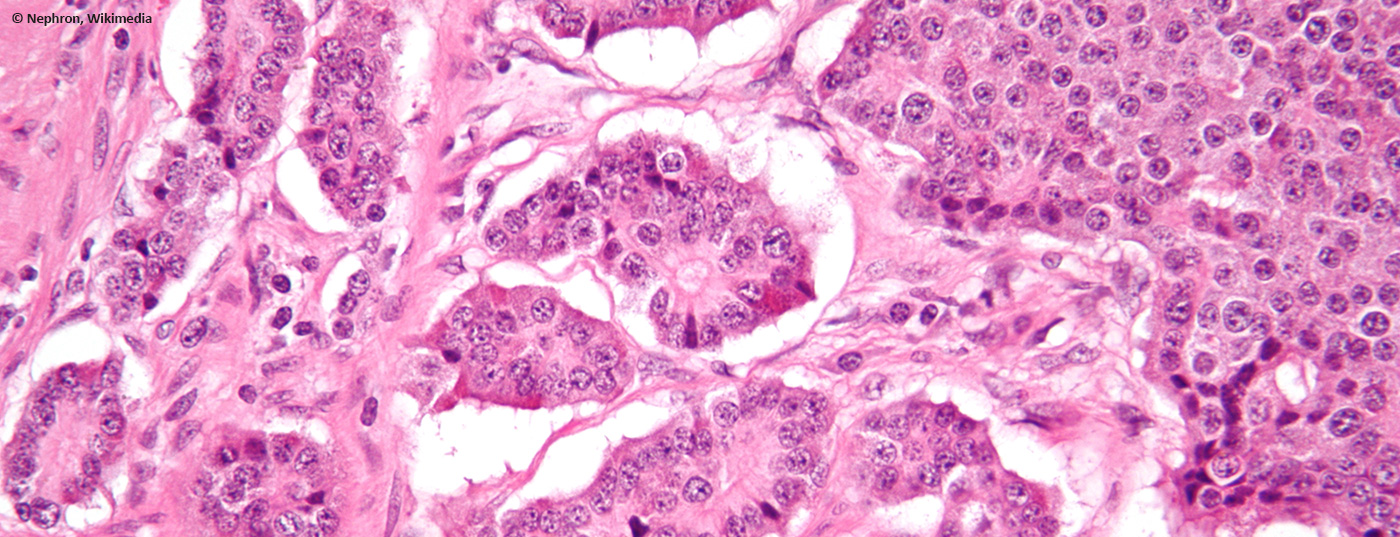

In any case, a biopsy is needed to confirm the diagnosis. Histopathological workup must include determination of typical markers (synaptophysin, somatostatin receptors [SSTR]) and mandatory proliferation rate (Ki-67 or MIB-1) or mitotic rate, as these are of considerable prognostic as well as therapeutic importance. In the case of a suspected carcinoid syndrome, the determination of 5-hydroxy-indoleacetic acid (5-HIESS, a degradation product of serotonin) in 24-hour urine is diagnostic. Other fasting laboratory values such as chromogranin A (CgA) and, if necessary, neuron-specific enolase (NSE) can be applied as tumor markers. Depending on the clinic, other tests are used (for example, the fasting test in insulinoma). As a future perspective, a new method must also be mentioned here: the so-called NETest [2]. It is a PCR diagnostic from whole blood (“liquid biopsy”), with which 51 NET-specific mRNA strands are examined. The positive predictive value for the diagnosis of neuroendocrine neoplasia is over 90%, as is the sensitivity and specificity. Initial reports have demonstrated its utility both for diagnosis and for monitoring treatment response. At present, however, this NETest is not yet widely available.

Imaging

In addition to standard imaging, nuclear medicine functional imaging plays a critical role in both staging and therapy selection. Foremost among these is 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT, which has steadily replaced the less precise and more complex octreotide scintigraphy in recent years [3]. Due to this significantly more sensitive PET examination, it is not uncommon for upstaging to occur due to the detection of metastases not visible on computed tomography. In addition, it can be used to detect the frequent presence of SSTR2 expression at the cell surface of NET, and thus evaluate the potential use of radionuclide therapy (PRRT, see below). If the proliferation index is high or if SSTR2 expression is absent or heterogeneous, additional performance of FDG-PET/CT is reasonable [4], because FDG-avid lesions indicate a more aggressive behavior and should be additionally biopsied whenever possible.

New WHO classification

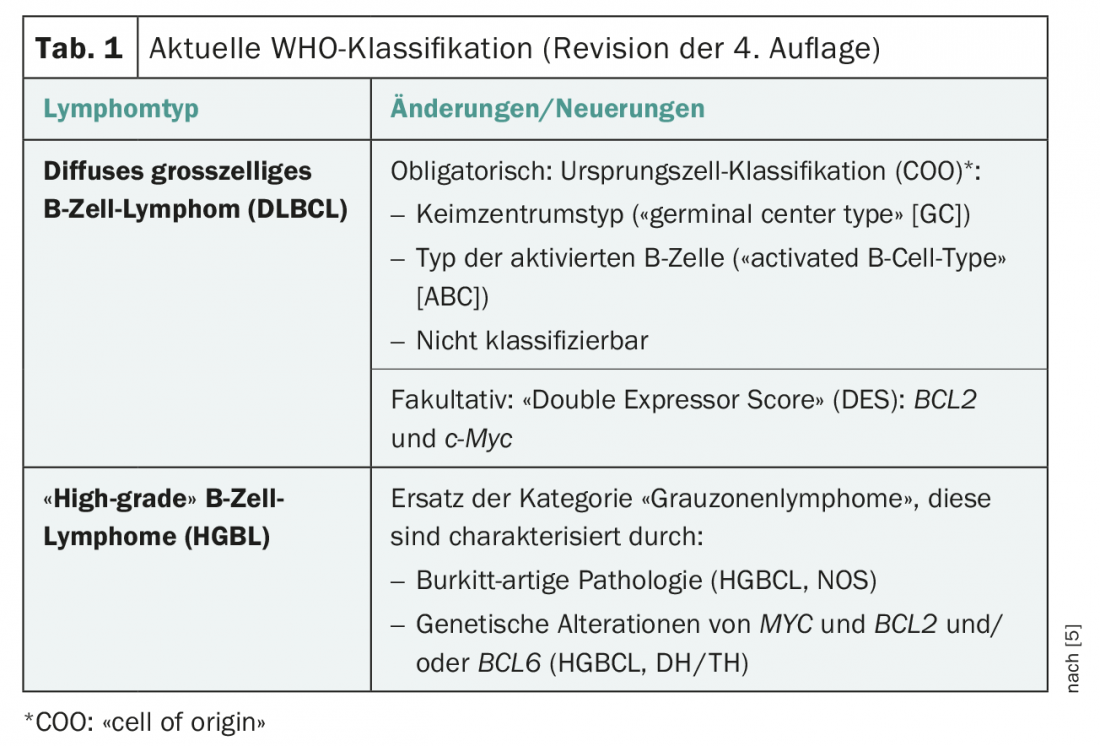

Over the last decades, there have been significant changes in the classification of neuroendocrine neoplasms thanks to new histopathological and clinical findings (Table 1) . The current WHO classification (2017), especially for pancreatic NENs (new: panNENs), has changed the discrepant histopathological (high proliferation index

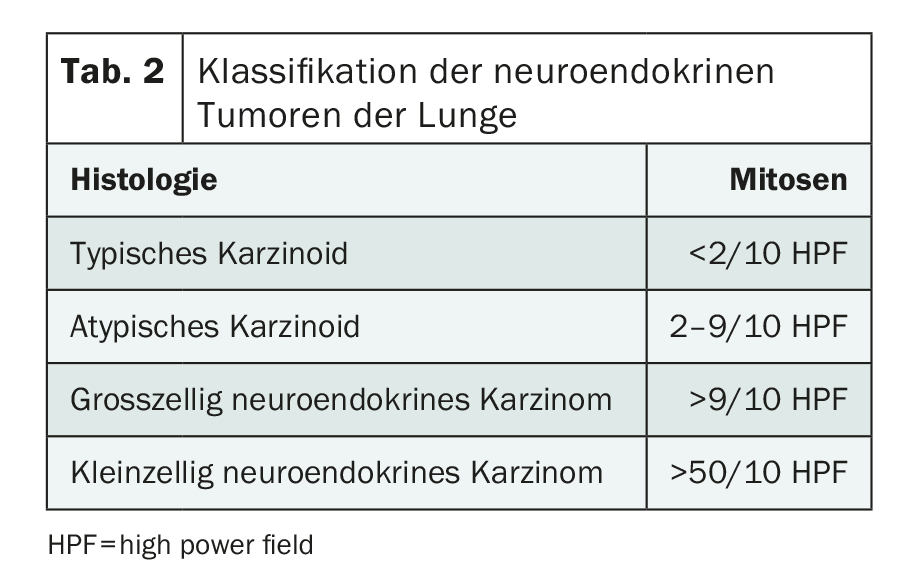

but low mitotic rate) and clinical features (prognosis) were taken into account. This results in the subdivision into NET G1, NET G2, NET G3 and NEC G3. The term “carcinoid” should be applied only to lung NET since the 2010 classification (Table 2).

Treatment of non-metastatic NET and follow-up.

The only potentially curative option for neuroendocrine neoplasms is complete tumor removal. In the gastrointestinal tract, this can be done endoscopically depending on the size (up to 2 cm) and situs. However, the indication for surgical resection should be made low-threshold when there is evidence of muscularis propria (T2) infiltration or lymph node metastases [5]. NET of the appendix represent a special situation. In the vast majority of cases, it is an incidental finding following appendectomy. The decision to perform supplemental right hemicolectomy with lymphadenectomy depends on tumor size (>2 cm), depth of penetration (>3 mm) into the mesoappendix, and vascular (V1) or lymphatic (L1) invasion [6].

In contrast to other tumor entities, there is no indication for adjuvant therapy in neuroendocrine tumors. Regular follow-up with annual endoscopies for NET of the stomach or rectum are recommended. In locally advanced but surgically completely removed NET, annual imaging (usually CT thoracic abdomen with i.v. contrast) should be performed throughout life.

Therapeutic option for metastatic NEN

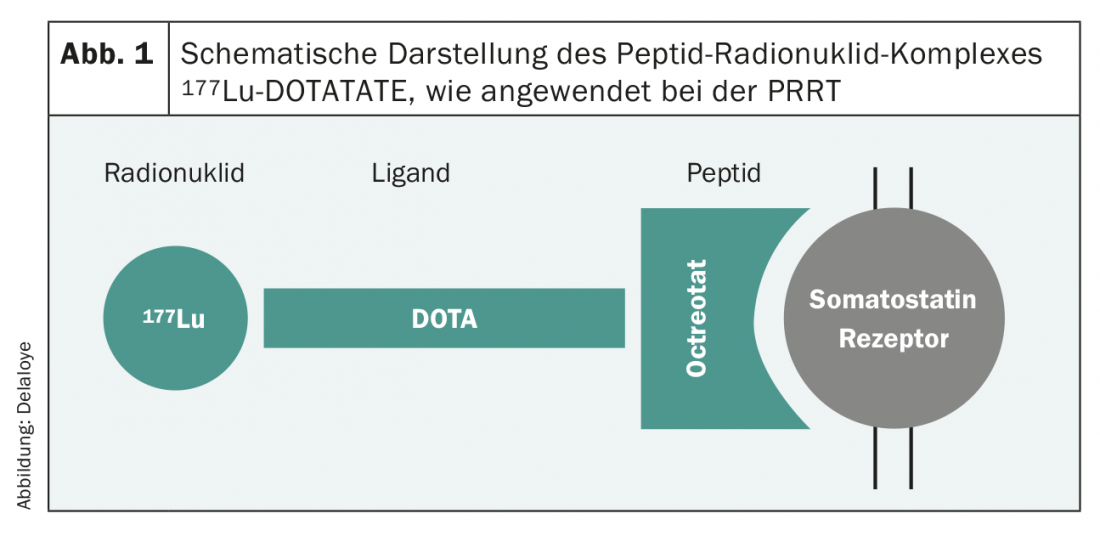

New developments in the last decade have dramatically improved the therapeutic landscape and thus patient survival. The number of practice-relevant phase III trials has grown quasi-exponentially, and recommendations from professional societies are based on increasingly solid evidence. Basically, the treatment options for G1 and G2 tumors are very similar. In this patient population, special attention must be paid to the side effects of therapy, as most are asymptomatic patients. In SSTR2-expressing tumors, numerous studies have established the use of first-line somatostatin analogues [7,8], even in nonfunctional tumor. This therapy, which is usually well tolerated, often leads to good tumor control and thus to a prolongation of progression-free survival. Peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT) is another option. A procedure in which a radioactive substance (90Yttrium or 177Lutetium) bound to a somatostatin receptor affine peptide (Octreotide/Octreotate) (Fig. 1) is administered intravenously as an infusion, allowing targeted irradiation of SSTR2-positive tumor cells. This treatment is usually applied four times in a row, each eight weeks apart. Again, this is a therapy that is usually very well tolerated, and the results of which were proven a few years ago in a large-scale phase III study [9].

At the molecular level, the use of everolimus as an mTOR inhibitor has been established. The cell proliferation mechanism around the PI3K-mTOR pathway plays an important role in neuroendocrine neoplasms, as in other tumors. Thus, good tumor control can be achieved with everolimus [10], but this therapy is associated with significantly more side effects.

Chemotherapy is also used for higher proliferating G2 NET and for G3 NET. A phase II study demonstrated antitumor activity of capecitabine and temozolomide (CapTem) in this patient cohort [11]. Although phase III data are still lacking, this therapy has proven itself in practice and has rapidly established itself as an alternative to the earlier combination of streptozotocin and 5-fluorouracil (STZ+5FU). The side effect profile is also favorable here and the handling is simple.

Higher grade neuroendocrine neoplasms (namely NEC G3) are treated with a combination of platinum and etoposide analogous to the therapy for small cell bronchial carcinoma. New therapies with checkpoint inhibitors have so far shown little success and cannot generally be recommended. They will be further investigated in clinical trials.

Take-Home Messages

- Cells with histological characteristics of glandular tissue, usually diffusely present in various organs of the body and capable of secreting hormones, are termed “neuroendocrine.” If they degenerate, they are referred to as neuroendocrine neoplasms (NEN).

- Most NEN originate from the gastroenteropancreatic space, with approximately 25-30% originating from the lungs.

- Functional tumors, such as insulinomas or gastrinomas, are rare but then lead to severe, potentially life-threatening hypoglycemia or multiple gastric ulcers.

- However, NENs are usually nonfunctional and are diagnosed either as incidental findings or in the context of nonspecific complaints.

- The only potentially curative option for nonmetastatic neuroendocrine neoplasms is complete tumor resection. In contrast to other tumor entities, there is no indication for adjuvant therapy in neuroendocrine tumors.

- Treatment options for metastatic NEN have improved significantly. For SSTR2-expressing tumors, the use of somatostatin analogues has become established. Higher grade neuroendocrine neoplasms are treated with a combination of platinum and etoposide analogous to the therapy for small cell bronchial carcinoma.

Literature:

- Cives M, et al: CA Cancer J Clin 2018; 68: 471-487.

- Modlin IM, et al: Endocr Relat Cancer 2014; 21(4): 615-628.

- Deppen A, et al: J Nucl Med 2016; 57(6): 872-878.

- Kayani I, et al: Cancer 2008; 112(11): 2447-2455.

- Delle Fave G, et al: Neuroendocrinology 2016; 103(2): 119-124.

- Pape UF, et al: Neuroendocrinology 2016; 103(2): 144-152.

- Rinke A, et al: J Clin Oncol 2009; 27(28): 4656-4663.

- Caplin ME, et al: N Engl J Med 2014; 371(3): 224-233.

- Strosberg J, et al: N Engl J Med 2017; 376(2): 125-135.

- Yao J, et al: Lancet 2016; 387: 968-977.

- Strosberg JR, et al: Cancer 2011; 117(2): 268-275.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2019; 7(1): 16-18.