Schizophrenic disorders in childhood and adolescence are rare but serious conditions. Diagnosis is a challenge because the symptoms often develop insidiously and – compared to those of adults – are more non-specific. Schizophrenic disorders in childhood and adolescence are associated with a worse prognosis than in adulthood. However, studies show that early detection and treatment significantly improves prognosis. Therefore, if schizophrenic development is suspected, early consultation with specialists is highly recommended. For children and adolescents who are in an at-risk stage, symptoms are monitored regularly and comorbid disorders are specifically treated. In children and adolescents with schizophrenia, treatment with antipsychotics is the first-line treatment. Building trust, conveying a positive attitude and specific reintegration measures are important elements for a positive course.

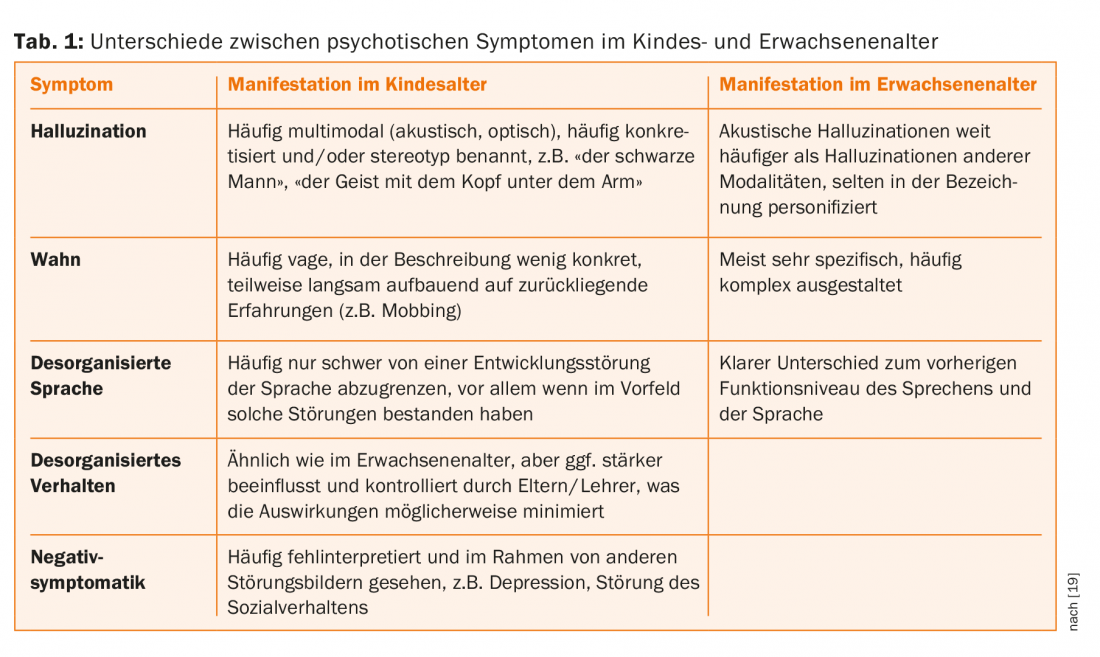

Schizophrenic disorders usually begin in adolescence or young adulthood. In childhood, they are very rare and much more difficult to diagnose because they often differ from adult schizophrenia in terms of symptomatology (tab. 1) . The symptoms of the disease can also show a great similarity with various developmental disorders, which makes diagnostic assignment even more difficult [1,2]. Therefore, it is not justified to apply adult criteria one-to-one to childhood. With increasing age, the symptomatology approaches that of adult patients, but the course in adolescents is more fluctuating than in adults.

Symptoms of schizophrenic disorder

Schizophrenic disorders are usually characterized by persistent psychotic symptoms that cannot be explained by other organic causes. Experts distinguish between positive and negative symptoms. Positive symptoms include delusions, hallucinations, ego disorders, and disorganized thinking and acting. As a rule, social perspective-taking develops by the age of six. Therefore, children as young as school age are capable of developing positive symptoms in the form of diffuse delusions, ideas of relationships and impairment, and abnormal experiences of meaning. In their structural makeup and content, the delusional phenomena of adolescence are no different from those of adults. In adolescence, however, these are less systematized. Hallucinations of all sensory modalities are common in children and may occur in the context of anxiety, extraordinary mental stress, or exceptional physical conditions such as high fever. In schizophrenias with childhood onset, 80% of affected individuals report visual hallucinations and 90% report auditory hallucinations [3]. In adulthood, visual hallucinations are comparatively less common (35%).

Negative symptoms include apathy, lack of spontaneity, decreased activity, impoverishment of speech, lack of initiative, and reduced nonverbal communication. The flattening of affect is not infrequently accompanied by a loss of drive and interest. Depressive and dysphoric symptoms often accompany the onset of psychotic illness. Assigning psychotic symptoms to a schizophrenic or affective disorder is often difficult in adolescence [4].

Onset of illness, duration of untreated psychosis, and prognosis.

The prognosis at the onset of schizophrenia in childhood is significantly worse than in adulthood. Children suffering from schizophrenia show more severe developmental neurological and cognitive deficits with marked brain structural changes [5,6]. This leads to greater impairment in functional levels at a critical stage of personal development, with significant consequences for further education and social integration [7].

There is increasing evidence from clinical and neurobiological research that early treatment can positively influence the course and prognosis of psychotic disorders [8]. Studies have shown that the duration of untreated psychosis is significantly longer in adolescents than in adults [9]. There are various reasons for this: pronounced and insidious symptomatology, an atypical picture that is often misinterpreted as a pubertal crisis, as well as the incorrect classification of the symptomatology because other diagnoses already exist. In addition, the families concerned initially seek help from other services. As a result, those affected are later presented to child and adolescent psychiatrists.

It seems a good approach to shorten the duration of untreated schizophrenia to also reduce the serious consequences of the disease [10,11]. Symptoms of a developing psychotic disorder are best recognized, followed up, and treated as early as possible.

Centers for the early detection of psychosis

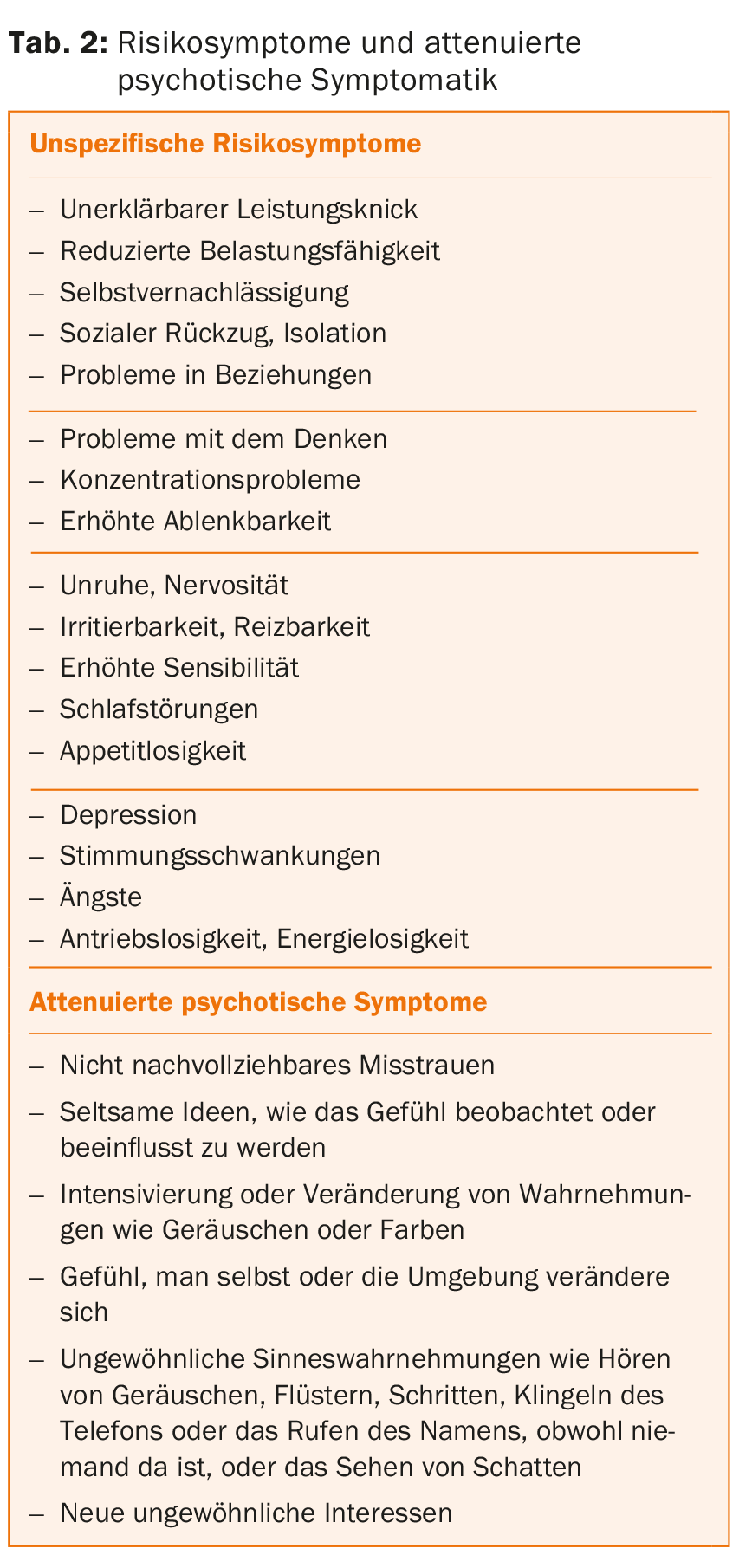

Early psychosis detection centers have been created around the world to help experts address this complex disorder and provide optimal treatment to patients at an early stage. The creation of such centers led to a reduction in the duration of untreated psychosis and reduced false-positive or false-negative diagnoses. Experts are also accustomed to involving the family and psychosocial environment of newly ill children and adolescents in indicated and specific treatment. However, family physicians and pediatricians continue to play a central role in the early detection of psychosis, as they can recognize warning signs of a potentially psychotic illness and should actively inquire about them so that expert help can be sought early (Table 2).

The early diagnosis consultation for psychotic disorders at KJPP Zurich offers a detailed diagnosis and integrative treatment. Individual and group therapies and networking with the various institutions are an important part of the support.

Clarification

The diagnostic workup of incipient psychotic disorders includes a detailed personal history with a precise survey of personal, educational and psychosocial development. Past or current use of drugs should be inquired about in detail, as the use of tetrahydrocannabinol and synthetic drugs, which is very common among adolescents, may increase the risk of psychosis. The family history is used to record possible family history. Clarification of premorbid and comorbid psychiatric disorders is very important, as pre-existing disorders are associated with an increased risk of developing a psychotic disorder.

Testing intelligence can help to identify partial performance disorders or cognitive deficits that already exist or have developed in the course of psychotic development, especially in children and adolescents in education. We consider a somatic examination with laboratory, EEG and cranial MRI very important to be able to exclude possible organic causes.

Ultra-High-Risk Stage

With the creation of expert centers, more and more children and adolescents are presenting with precursor symptoms (Table 2) . These children and adolescents are in an “ultra-high-risk stage” (UHR) for the development of a psychotic disorder, also called “at-risk mental state” or “prodrome.” They should be monitored regularly so that a possible transition to a manifest first psychotic episode can be detected in time.

However, the significance of UHR in children and adolescents is more uncertain than in adults. A recently published meta-analysis on the predictive value of UHR criteria for the development of psychosis describes a lower transition rate after one year of follow-up in the child and adolescent group compared to the adult group. Current research is focused on more specific criteria and markers in children and adolescents to achieve better predictive power (predictivity) and specificity [12]. Already today, specific instruments allow the differentiated, early, qualitative and quantitative recording of such precursor symptoms; these include the “Schizophrenia proneness instrument for childhood and youth” (SPICY), the “Structured interview for prodromal symptoms” (SIPS) and the “Comprehensive assessment of at risk mental state” (CAARMS).

In children and adolescents confirmed to have UHR, specific psychological and psychosocial interventions are recommended with the goal of buffering losses in functioning and preventing progression to manifest psychosis. An important component of treatment is therapy for comorbid disorders such as addictive disorders, depression, and anxiety disorders. Most important, however, is regular monitoring to detect potential transition to psychosis without delay. In general, initiation of antipsychotic therapy is recommended when psychotic symptoms are present for more than one week and are associated with functional impairment. Under these circumstances, experts would call it a transition. There have also been studies in which low-dose antipsychotics were used even before the transition to psychosis and have shown a protective effect on the progression of the disease. However, markers that justify its fundamental use in this group of adolescents are still lacking, as over 80% never develop schizophrenia.

There is also evidence that experimental therapies such as administration of high-dose omega-3 fatty acids produce a significant reduction in psychosis transitions. Currently, promising study results are being reviewed in two large-scale studies [13,14].

Treatment of schizophrenic disorder

Once a schizophrenic disorder is established, lifelong therapy is necessary in over 80% of cases. Therefore, it is important that the person concerned commits to a support that may last several years. Establishing trust, conveying a positive attitude, and ensuring continuity of the therapeutic relationship are important elements for a positive outcome.

In the acute phase, drug treatment is indispensable. First-line medications are atypical antipsychotics [15,16]. In the acute phase, the indication for inpatient treatment should be well considered because of the possible traumatic consequences for the patient and relatives. However, emergency admission is often unavoidable in cases of danger to self or others and decompensation of the family system.

Often, because of the disease, patients have lost the ability to understand the disease. Therefore, the first difficulty in the treatment of schizophrenic disorders is to convince patients to be treated with medication as well. The psychotherapeutic alliance and the building of trust between patient, relatives and therapist have a positive effect here.

The building blocks of psychotherapeutic treatment, in addition to extensive psychoeducation, are various interventions aimed at reducing the stress experienced and developing a healthy lifestyle that protects against relapse. Specific therapeutic approaches are used for persistent delusions or hallucinations. Therapeutically supervised practice of social skills is an important component of social reintegration. At the KJPP, group training is offered (DBT-2P): six to seven affected adolescents learn to develop strategies together in order to better deal with the psychotic symptoms and the illness. In addition to psychotherapeutic elements, occupational therapy interventions are also included so that impaired cognitive functions can be trained.

Smartphones can be useful in the treatment of children and adolescents: Currently, an app is being developed in our center that includes psychoeducational elements and skill lists to accompany therapy and enables the monitoring of symptoms and medication reminders.

After the acute phase, the next important step is to carefully prepare for educational and professional reintegration through education and involvement of the relevant institutions. Decisive for a better outcome – as two independent studies in Australia have shown – is on the one hand the possibility of remaining integrated in the school system, and on the other hand specific support in coping with age-typical developmental steps [17,18].

Literature:

- Bartlett J: Childhood-onset schizophrenia: what do we really know? Health Psychol Behav Med 2014; 2(1): 735-747.

- Gochman P, et al: Childhood-onset schizophrenia: the challenge of diagnosis. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2011; 13(5): 321-322.

- David CN, et al: Childhood onset schizophrenia: high rate of visual hallucinations. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2011; 50(7): 681-686.

- Calderoni D, et al: Differentiating childhood-onset schizophrenia from psychotic mood disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2001; 40(10): 1190-1196.

- Ordonez AE, et al: Neuroimaging findings from childhood onset schizophrenia patients and their non-psychotic siblings. Schizophr Res 2015. pii: S0920-9964(15)00132-2.

- Rapoport JL, Gogtay N: Childhood onset schizophrenia: support for a progressive neurodevelopmental disorder. Int J Dev Neurosci 2011; 29(3): 251-258.

- Driver DI, et al: Childhood onset schizophrenia and early onset schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 2013; 22(4): 539-555.

- Fusar-Poli P, et al: The psychosis high-risk state: a comprehensive state-of-the-art review. JAMA Psychiatry 2013; 70(1): 107-120.

- Schimmelmann BG, et al: Pre-treatment, baseline, and outcome differences between early-onset and adult-onset psychosis in an epidemiological cohort of 636 first-episode patients. Schizophr Res 2007; 95(1-3): 1-8.

- Johannessen JO, et al: First-episode psychosis patients recruited into treatment via early detection teams versus ordinary pathways: course and health service use during 5 years. Early Interv Psychiatry 2011; 5(1): 70-75.

- Nordentoft M, et al: The rationale for early intervention in schizophrenia and related disorders. Early Interv Psychiatry 2009; 3 Suppl 1: S3-7.

- Schultze-Lutter F, et al: EPA guidance on the early detection of clinical high risk states of psychoses. Eur Psychiatry 2015; 30(3): 405-416.

- Amminger GP, et al: Long-chain omega-3 fatty acids for indicated prevention of psychotic disorders: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2010; 67(2): 146-154.

- Amminger GP, et al: Longer-term outcome in the prevention of psychotic disorders by the Vienna omega-3 study. Nat Commun 2015; 6: 7934.

- Kendall T, et al: Recognition and management of psychosis and schizophrenia in children and young people: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ 2013; 346: f150.

- Schimmelmann BG, et al: Treatment of adolescents with early-onset schizophrenia spectrum disorders: in search of a rational, evidence-informed approach. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2013; 26(2): 219-230.

- Amminger GP, et al: Outcome in early-onset schizophrenia revisited: findings from the Early Psychosis Prevention and Intervention Centre long-term follow-up study. Schizophr Res 2011; 131(1-3): 112-119.

- McGorry PD, et al: EPPIC: an evolving system of early detection and optimal management. Schizophr Bull 1996; 22(2): 305-326.

- Sikich L: Diagnosis and evaluation of hallucinations and other psychotic symptoms in children and adolescents. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 2013; 22(4): 655-673.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2016; 14(2): 8-12.