Data from two phase III trials (both from the research group led by Caroline Robert, MD, Institut Gustave Roussy in Villejuif, Paris) published earlier this year highlight the rapid development in malignant melanoma. Nivolumab and the combination therapy of dabrafenib and trametinib may soon be available to patients with metastatic melanoma. Nivolumab also shows good results in BRAF wild-type, while the combination is an improvement for mutant cases.

Metastatic, ipilimumab-refractory melanoma responds better to the administration of nivolumab than to chemotherapy – that much is certain. The question of whether nivolumab also confers a benefit in previously untreated patients with advanced melanoma has now been investigated in phase III. The associated study, called CheckMate 066, appeared in the New England Journal of Medicine earlier this year (online since November) and attracted attention primarily because it was the first randomized phase III trial to demonstrate a survival benefit of PD1 blockade [1]. The drug has been approved in the USA since the end of December 2014. In the EU (and also in Switzerland), approval for advanced melanoma will probably not be long in coming.

PD1 blockade prolongs life

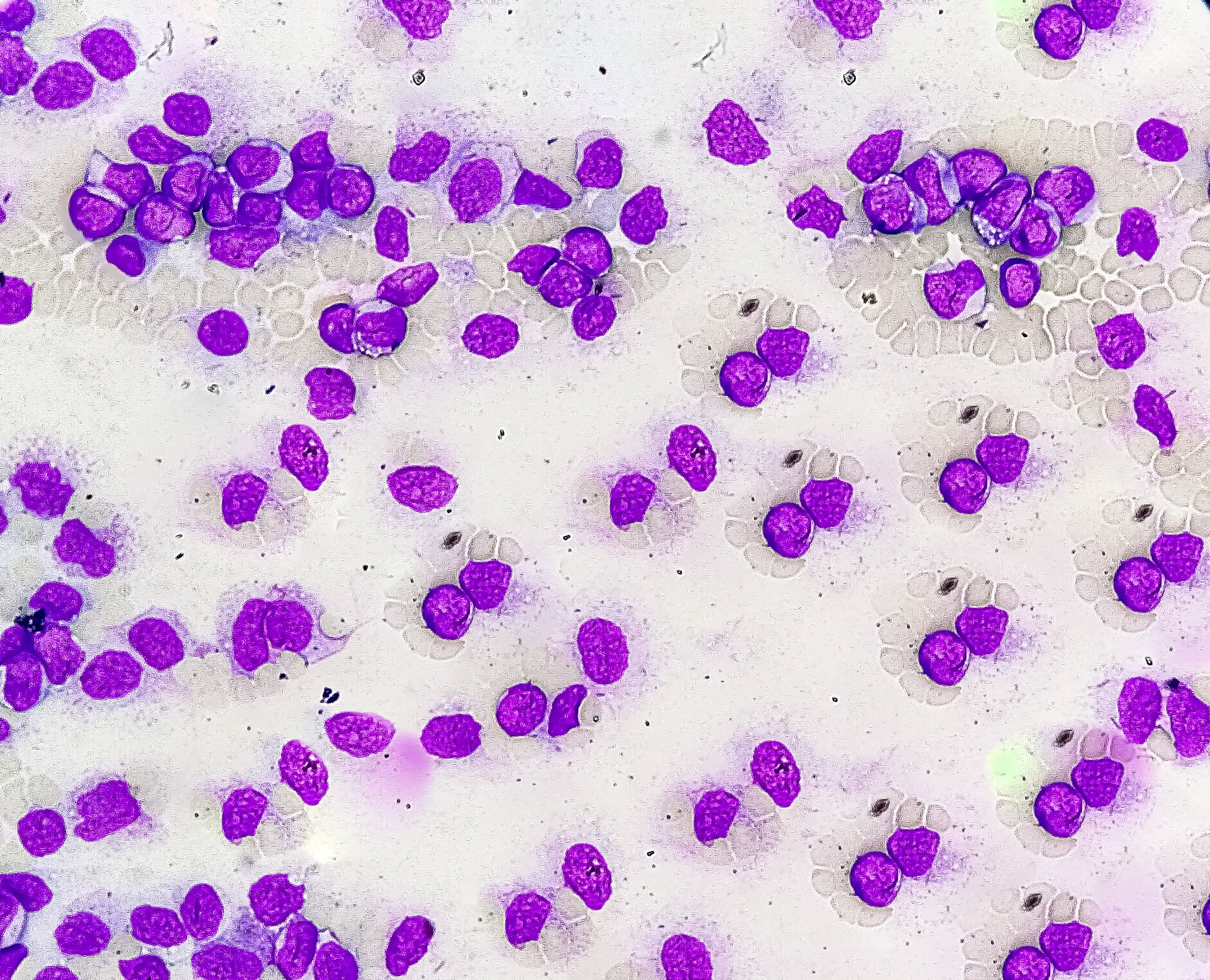

Nivolumab is an anti-PD1 (“programmed cell death protein 1”) antibody. The blockade results in enhanced T-cell tumor defense. The study included 418 treatment-naïve patients with stage III or IV metastatic melanoma (without BRAF mutation). They received either nivolumab or the standard first-line chemotherapeutic agent dacarbazine at the time of study design (2012). The dose was 3 mg/kgKG every two weeks in the nivolumab arm and 1000 mg/m2 every three weeks in the dacarbazine arm. Placebo was used to counterbalance the different treatment frequencies, which allowed blinding. The primary endpoint was overall survival (OS). In addition, progression-free survival (PFS) and response rate (according to RECIST criteria 1,1) were collected.

Turning to the hard facts, 72.9 vs. 42.1% (nivolumab vs. dacarbazine) of patients were still alive (OS) after one year , representing a remarkable 58% reduction in the risk of death (HR 0.42, 99.79% CI 0.25-0.73; p<0.001). Median PFS was 5.1 vs. 2.2 months. The antibody thus reduced the risk of progression or death by 57% (HR 0.43, 95% CI 0.34-0.56; p<0.001). The objective response rate was 40 vs. 13.9%. Thus, the odds of response were four times higher with nivolumab than with dacarbazine (odds ratio 4.06; p<0.001). Results were consistent across all prespecified subgroups.

Fatigue (20%), nausea (16.5%), and pruritus (17%) were frequently observed under the immune checkpoint inhibitor. Grade 3 and 4 adverse events were less frequent with nivolumab, occurring in 11.7 vs. 17.6% (dacarbazine) of cases. In addition, fewer patients discontinued therapy in the nivolumab group than in the chemotherapy group.

Combination – two stronger than one?

While CheckMate 066 focused on patients with BRAF wild-type, who make up about 60% of all melanoma patients, another study published in January 2015 focused on the other approximately 40% with BRAF V600 mutation. These patients benefit from the two substances vemurafenib (Zelboraf®) and dabrafenib (Tafinlar®), which are also approved in Switzerland. Both have proven their effectiveness several times.

In the phase III trial, the focus now shifted to the combination of dabrafenib and the MEK inhibitor trametinib, which is already approved in several countries but not in Switzerland [2]. Included were 704 previously untreated patients with advanced stage IIIC/IV metastatic melanoma and BRAF V600 mutation (90% with V600E and 10% with V600K). They received either the combination (dabrafenib 2× 150 mg/d, trametinib 1× 2 mg/d) or monotherapy with vemurafenib at the standard dose (2× 960 mg/d). The primary endpoint was overall survival.

The planned interim OS analysis showed that 72 vs. 65% (combination vs. vemurafenib) of patients were alive at one year. This corresponds to a significant 31% risk reduction by the combination (HR 0.69, 95% CI 0.53-0.89; p=0.005). Median PFS was 11.4 vs. 7.3 months, again a relevant 44% reduction in the probability of progression/death (HR 0.56, 95% CI 0.46-0.69, p<0.001). The objective response rate was 64 vs. 51%, and the difference was significant.

The number of serious adverse events and treatment discontinuations was comparable in the two study groups. A non-life-threatening but worrisome side effect of BRAF inhibitors is secondary skin tumors. The combination performed better than monotherapy with respect to this side effect: cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and keratoacanthoma appeared in only 1% of patients in the treatment combination but in 18% of patients in the vemurafenib group.

However, the main problem with kinase inhibitors, alone or combined, remains the development of resistance. It is apparently the price to pay for rapid response and remission. It is therefore not surprising that research efforts in this area are large. A longer-term solution is currently not yet in sight. Despite the downer, the extended lifespan under combination is remarkable and brings a decisive progress in the therapy of BRAF-mutated melanoma – especially because the benefit did not have to be bought with increased toxicity.

Literature:

- Robert C, et al: Nivolumab in Previously Untreated Melanoma without BRAF Mutation. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 320-330.

- Robert C, et al: Improved Overall Survival in Melanoma with Combined Dabrafenib and Trametinib. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 30-39.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2015; 25(2): 19-20