Introduction: Torsional vertigo is one of the most common acute neurological symptoms seen in emergency departments. We present a case example of the value of imaging techniques in determining the cause.

Case report: The 76-year-old, very spry patient was on vacation in Italy when he awoke acutely with severe spinning dizziness lasting for hours. Briefly, he also noticed obliquely displaced double vision, but this could not be objectified during the acute on-site examination. Persistently, he complained of almost complete hearing loss in the left ear. The wife also noticed that he moved the left side of his face less well and he spoke a little more slurred. At the local hospital, a CCT assessed as unremarkable was performed and no further measures were taken apart from bed rest. From the previous history, a biological aortic valve replacement in 2011 and oral anticoagulation with Marcoumar for atrial fibrillation with constant setting in the target range of INR 2.0 – 3.0 are worth mentioning. Otherwise, the routine laboratory was unremarkable and the patient was afebrile.

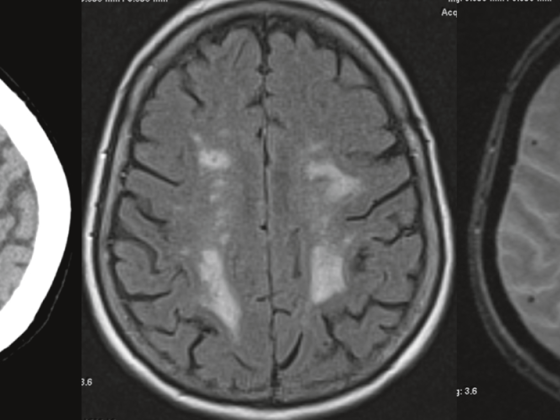

Less than a week after the event, the patient was repatriated. Clinical-neurological findings included stance and gait ataxia with mild left limb ataxia, oculomotor function that was unremarkable except for gross saccades during rapid gaze to the left, as well as incomplete (peripheral) facial nerve palsy on the left and severe hypacusis on the left, which was also objectified by ORL. On immediate MRI imaging, we found a subacute infarct in the left pons/middle cerebellar peduncle correlating with the neurologic findings, which reached the exit zone of the seventh and eighth cranial nerves in the inferior region (Fig. 1).

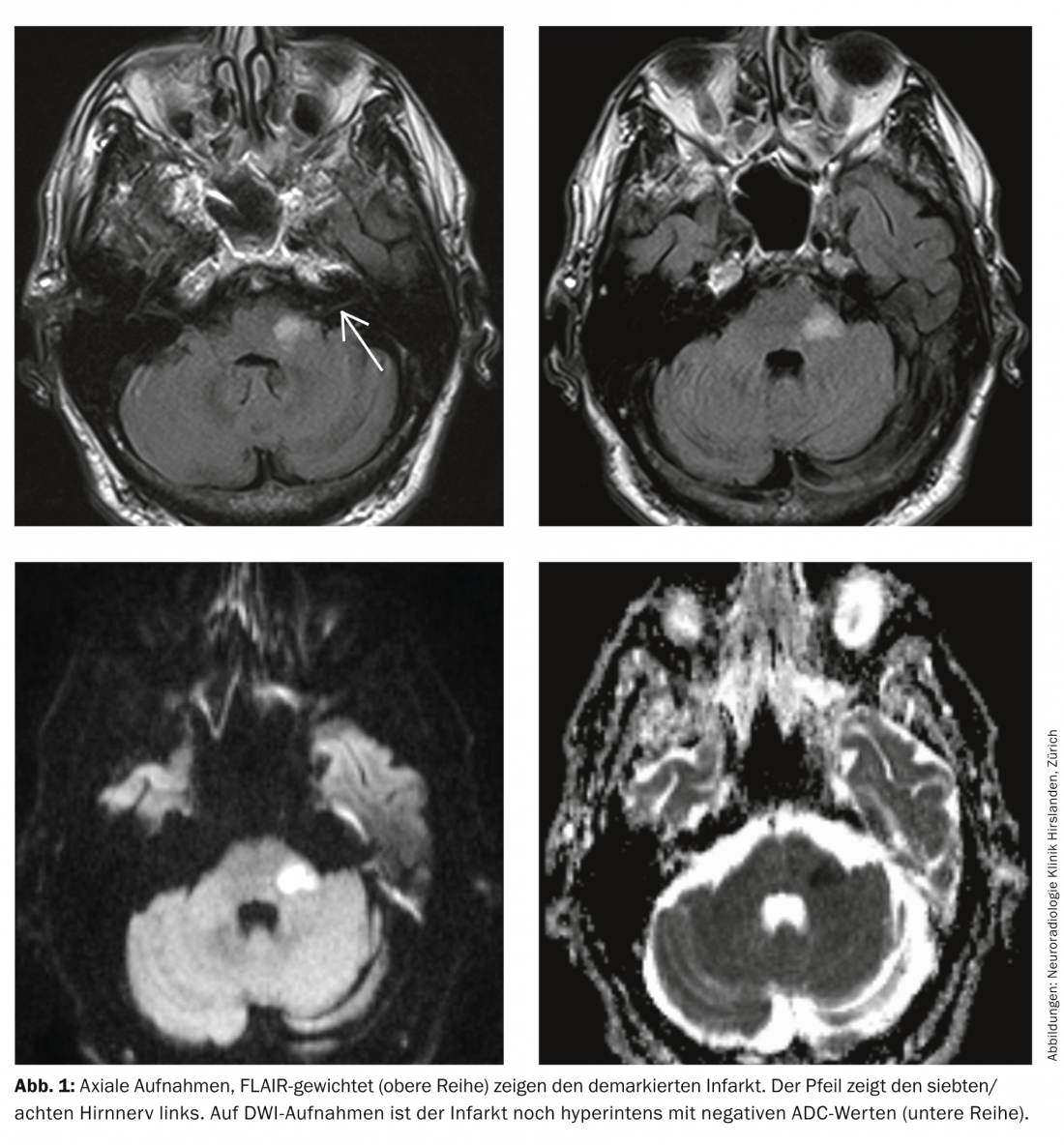

With an unremarkable vascular status, transesophageal echocardiography revealed a floating structure on the aortic valve prosthesis as the cause of the cerebral infarction, with positive blood cultures (gram-positive cocci) confirming the suspicion of valve endocarditis (Fig. 2) . Under antibiotic therapy, the finding was no longer detectable in short-term TEE monitoring. The further clinical course was without complications, the hypacusis remained unchanged, but the patient could be mobilized well.

Discussion: Acute spinning vertigo in combination with other neurological symptoms must suggest brainstem ischemia and be clarified as soon as possible by MRI.

This is true even in the absence of symptoms on the part of the long tracts. In our case, this would have enabled the rapid initiation of therapy. Our patient had the rare combination of facial nerve palsy and acute, severe hearing loss, which is understandable because of the infarct topography in the area of the entrance or exit zone from the seventh and eighth cranial nerves.

Achim Mallmann, MD

Manfred Ritter, MD

Prof. Dr. med. Stephan Wetzel

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2014; 12(3): 24-24.