Guideline recommendations for surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation (AF) vary, and often the success of treatment is closely tied to experience of the treating hospital, patient co-morbidities, and intensive interdisciplinary exchange between electrophysiologists and cardiac surgeons. Further, there appears to be no consensus among cardiac surgeons regarding indication, surgical technique, and postoperative care. Since 2009, Inselspital has implemented a new algorithm of surgical treatment of VCF in interdisciplinary collaboration, which includes a uniform concept for indication, intraoperative technique, postoperative care and follow-up.

Atrial fibrillation (VHF) is the most common cardiac arrhythmia. In the Western world alone, approximately 1% of the population suffers from VCF. The incidence increases with increasing age [1, 2]. The risk for VCF increases considerably with the severity of existing heart disease. Thus, a prevalence of 4% was found in stage NYHA I heart failure, a prevalence of about 25% in stages NYHA II and III, and as high as 50% in stage NYHA IV.

Mortality is about twice as high in VHF as in sinus rhythm peers, but this is predominantly or exclusively due to the more common cardiac diseases. On average, about 6% of patients with VHF have a stroke each year, and 15-20% of all strokes are associated with VHF. The “Euro Heart Survey” for VHF identified the increasing number of hospitalizations and the increasing rate of interventional procedures as the main economic cost drivers in VHF. Thus, interest in developing successful approaches to the treatment of VCF that promote primary or secondary prevention is warranted [3].

Both the AFFIRM and RACE trials have shown that purely rate-controlling drug therapy combined with oral anticoagulation in elderly, low-symptomatic patients is equivalent to drug-controlling rhythm therapy in terms of mortality. However, less than 30% of patients are treatable with medication or electrical therapy. In addition, antiarrhythmic drugs often show moderate long-term success at best and frequently have undesirable side effects. In contrast, interventional or catheter-based radiofrequency ablation has been shown to be an effective therapy for symptomatic recurrent and drug-refractory VCF [5]. Nevertheless, with the catheter procedure, success rates for paroxysmal VCF are approximately 60-80% with first-time use; 30-40% of patients require at least a second intervention [6–8]. However, long-term success rates continue to decline over the years: survival without arrhythmia is reported in only 29-53% of patients [9–11]. For patients with persistent VCF, the pendulum does not swing in favor of interventional ablation because repeated and extensive ablations are usually required [12–14]. Given the limitations of pharmacological and interventional therapeutic options, surgical ablation of VCF is becoming increasingly important.

VHF: evolution of surgical treatment

In 1980, Williams et al. [15], five years later Guiraudon et al. [16] the first surgical treatments for VHF. These methods attempted to channel the electrical pathways by means of incisions in the left atrium so that regular conduction in the ventricles could be guaranteed. Both methods failed because larger portions of the atria continued to show VHF, thus failing to ensure atrial transport and leaving the risk of thromboembolism unchanged.

In 1991, Cox [17] presented the first so-called maze operation (Cox-Maze I). The concept is based on two assumptions:

- Fractionation of the atrial tissue into small segments suppressed multiple ‘re-entries’, he added

- However, these small segments should still be connected to allow depolarization of sufficient myocardial tissue.

Ferguson and Cox [18] defined five goals of surgical treatment of VCF: elimination of VCF, restoration of sinus rhythm, atrio-ventricular synchrony, preservation of atrial transport function, and prevention of stroke.

Using the more advanced Cox-MAZE III operation, sinus rhythm is achieved in 75-98% of cases, and transport function is restored in 81-86%. The 10-year follow-up shows a stroke incidence of <1%. The effect on survival is still unclear. However, the process is time-consuming and requires practice. It is now possible to mimic the original complex atrial fragmentation of Cox-Maze III surgery with less effort using various hyperthermic or hypothermic energy sources (especially radiofrequency ablation). Success rates of this method – called surgical ablation or Cox-Maze-IV – show comparably good results: However, sinus rhythm occurs in 70-98% of cases with a single procedure [19–29], depending on short- or long-term outcome.

Guidelines

Recommendations for surgical treatment of VCF vary. The only randomized trial comparing surgical versus interventional catheter ablation showed higher freedom from atrial arrhythmias one year after surgical intervention but a higher complication rate compared with the catheter-technical method [30]. The experience of the treating hospital, co-morbidities and wishes of the patient and an intensive interdisciplinary exchange between electrophysiologists and cardiac surgeons are part of the therapeutic decision.

The 2010 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines for the treatment of VCF recommend surgical ablation for:

- Symptomatic patients with VCF undergoing cardiac surgery anyway (IIA-A).

- Asymptomatic patients undergoing cardiac surgery anyway should also be considered for surgical ablation if the procedure carries little additional risk and a good chance of success and if an experienced surgeon performs the procedure (IIB-C).

- Patients with VCF who have no other indication for cardiac surgery or in whom catheter ablation has been unsuccessful and minimally invasive surgical ablation is possible (IIB-C).

The 2012 EHRS-EHRA-ECAS expert recommendations for surgical ablation apply:

- For patients with symptomatic paroxysmal or persistent VCF who have any other indication for cardiac surgery (IIa-C).

- Patients with drug-resistant VCF (antiarrhythmic class 1 or 3), paroxysmal or persistent, without any other indication for cardiac surgery and after unsuccessful catheter ablation, or patients who prefer surgical ablation themselves (IIb-C).

Surgical ablation of the VHF as a concomitant operation

The prevalence of VCF in patients undergoing cardiac surgery varies from approximately 2% (for aorto-coronary bypass surgery) to 60% for mitral valve surgery [31, 32]. Because an untreated, long-standing, persistent VCF is very unlikely to convert spontaneously to sinus rhythm and because VCF alone may also affect long-term survival, it is reasonable to perform additional ablation when cardiac surgery is indicated anyway [33, 34]. Even in valvular-induced VHF, correction of valve pathology alone is not enough to treat the arrhythmia. It appears that electrical isolation of the pulmonary vein orifices alone is effective enough to treat paroxysmal VCF [35]. It is still unclear whether bi-atrial ablation is better than left atrial ablation alone in all cases [36].

Efficiency of surgical ablation and patient follow-up.

The consensus published in 2007 between the Heart Rhythm Society, Society for Thoracic Surgeons, European Heart Rhythm Association, and the European Cardiac Arrhythmia Society [37] contains a recommendation for reviewing the success of therapy and further treatment of the patient after surgical or interventional ablation. However, the reality in clinical practice and in most publications, especially after surgical ablation, is different: Very few physicians adopt the above recommendations. In addition, there appears to be no consensus, even among cardiac surgeons, regarding indication, surgical technique, and postoperative care. Thus, neither surgeons themselves nor electrophysiologists can prove the efficacy of surgical therapy or of introduced modifications. To circumvent this hurdle, a new algorithm of surgical treatment of VCF was introduced at Inselspital from February 2009 in an interdisciplinary approach involving electrophysiologists and internists. This includes a uniform concept for indication, intra-operative technique, post-operative care and follow-up.

New Algorithm of Surgical Atrial Fibrillation Ablation

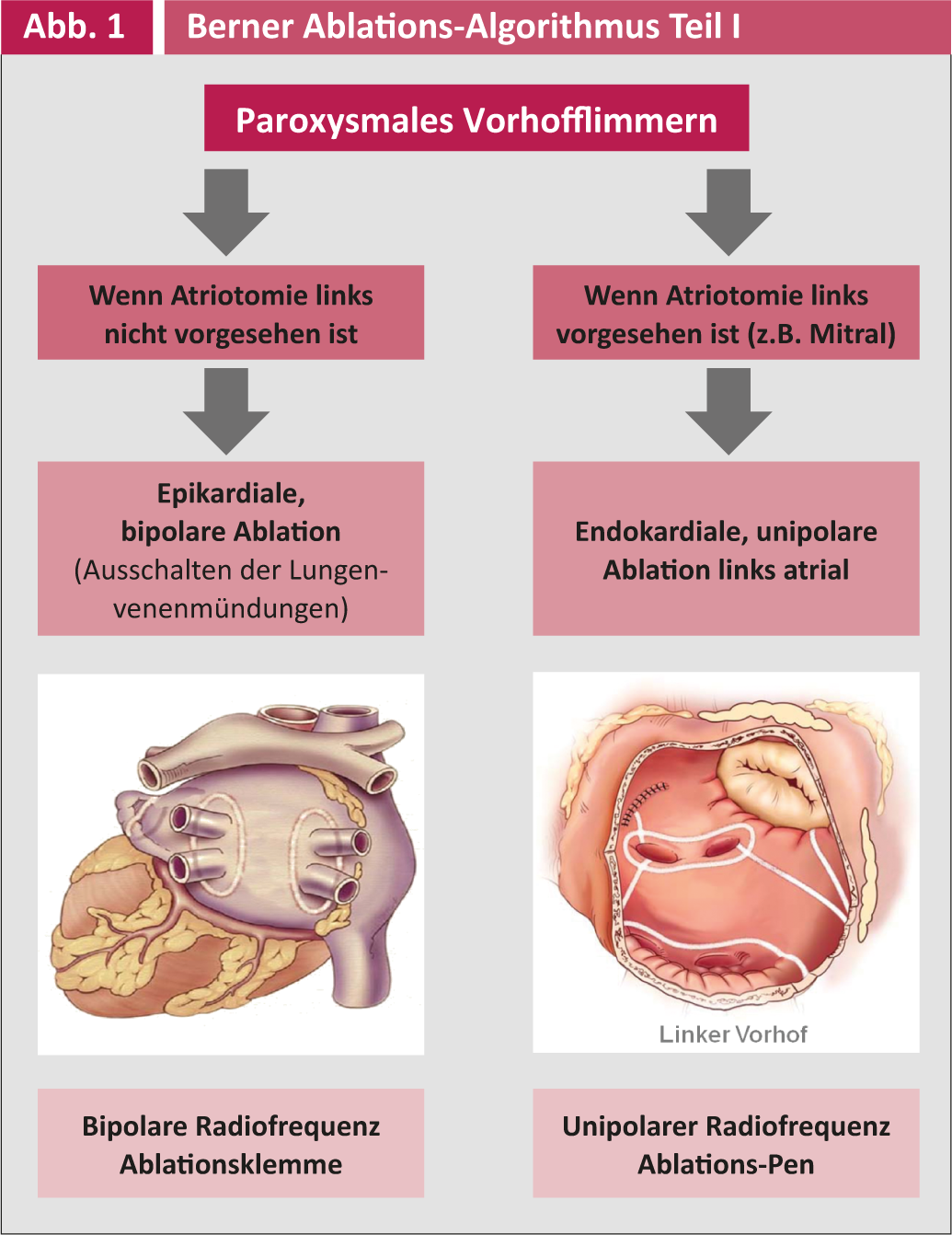

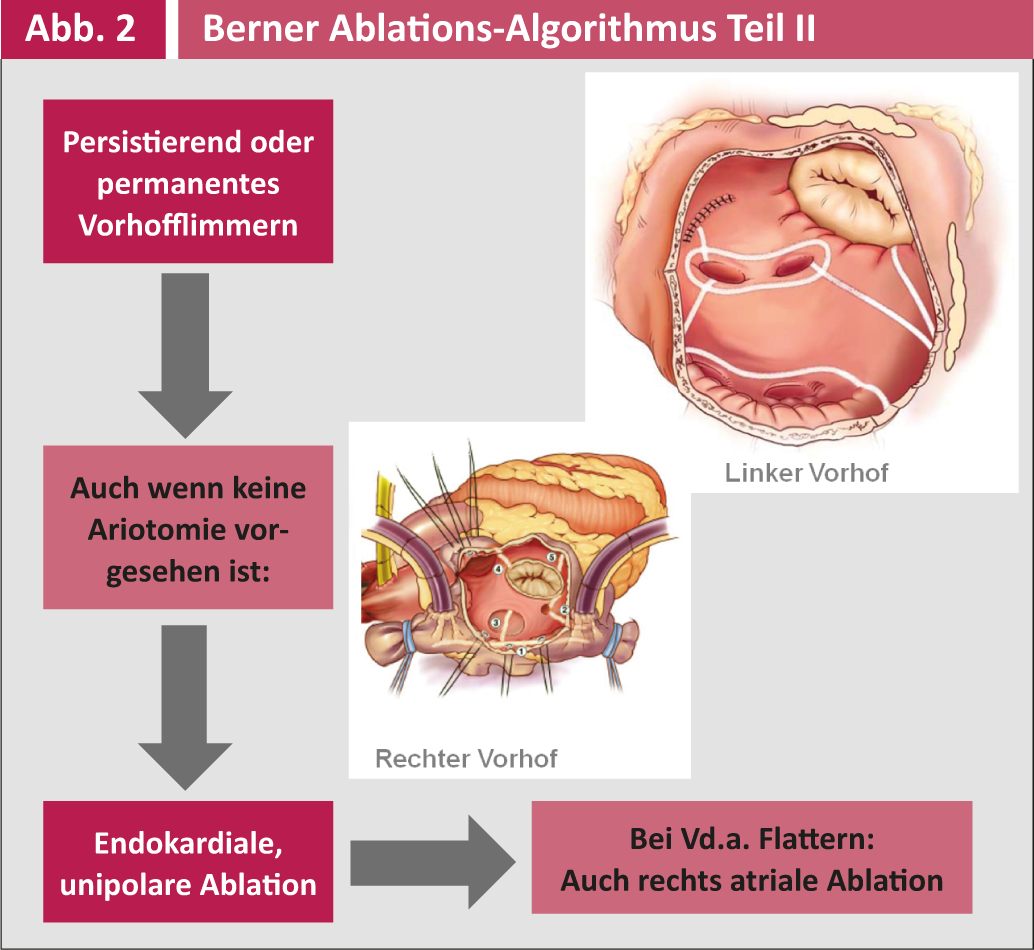

The indication for surgical ablation as an adjunctive operation in other cardiac surgical procedures and the corresponding surgical technique are summarized in Figures 1 and 2.

Postoperative antiarrhythmic therapy is managed by the cardiologists/internists and includes primarily metroprolol and secondarily amiodarone. Postoperative follow-up is performed three times monthly during the first year and annually thereafter by the electrophysiologists at Inselspital or cardiologists in private practice. All controls include a 7-day event recorder long-term ECG (R test) to detect asymptotic episodes of VCF and adjust antiarrhythmic or anticoagulation therapy accordingly. Electrical success can only be said to have occurred if no VHF or atrial arrhythmia appears >30 seconds in a seven-day period. A clinical success, on the other hand, is the patient’s freedom from symptoms, even if asymptomatic recurrences still occur.

Intraoperative resection or elimination of the left atrial ear for thromboembolism prophylaxis is performed if the CHADS-VASC score is ≥2, the patient has a history of TIAs, and/or if fibrin or thrombus is localized in the left atrial ear by inspection, or echocardiography. It has been demonstrated that an intact atrial ear contributes significantly to left atrial transport. In addition, the water balance of the body plays an important role [38–44].

The primary end point of this continuous analysis is freedom from episodes of atrial fibrillation in the R test. The secondary end points are freedom from oral anticoagulation, freedom from antiarrhythmic medication, rate of cerebral stroke, and identification of possible predictive factors for stable sinus rhythm. A full follow-up is mandatory.

Provisional results and partial analysis

Since the introduction of a new ablation algorithm in 2009, 144 patients who had VHF in addition to their respective heart disease were treated intraoperatively by surgical ablation using the new algorithm. 64% of patients were ablated with unipolar radiofrequency, 29% patients with bipolar radiofrequency, and 7% patients with another energy source (cryothermia).

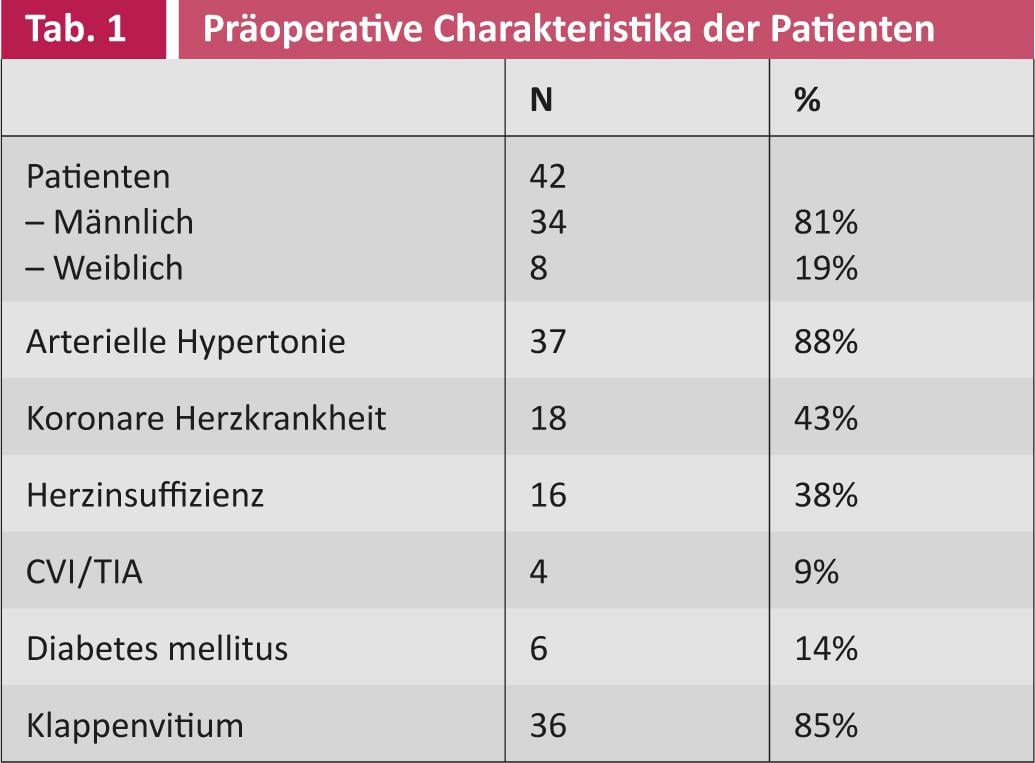

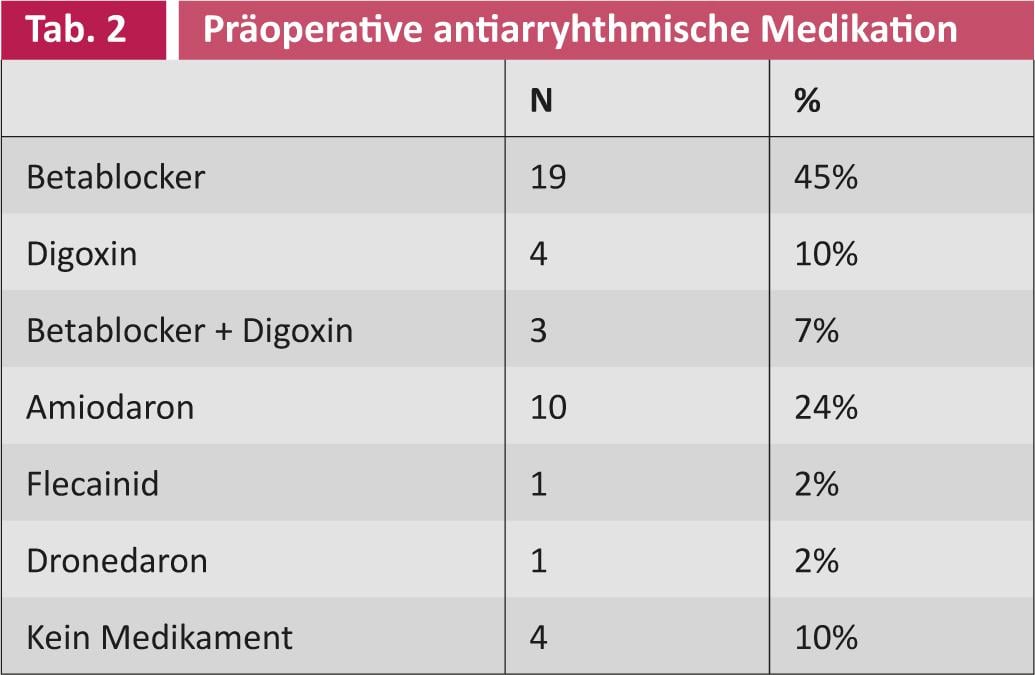

A partial analysis of the first 42 patients showed that before surgical intervention, 21 (50%) patients suffered from paroxysmal and 21 (50%) from persistent VCF. The mean duration of illness was 26 months (SD 40.5). The mean age at the time of intervention was 69 years (SD 7.8). Thirty-four (81%) patients were male and eight (19%) were female. The different preoperative patient profiles are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

Thirty (71%) patients were orally anticoagulated before surgical ablation. The mean CHADS2 score or CHA2DS2-VASc score was 2 resp. 3 (SD 1 resp. 1.5). Because of the risk of thromboembolism, the left atrial ear was ligated in 18 (43%) of the patients, and it was completely removed in two (5%) patients. Thus, in most patients, the atrial ear was left intact. As mentioned earlier, surgical ablation was performed with another procedure on the heart. The operation time is only slightly prolonged, the additional time required is about 15-20 minutes.

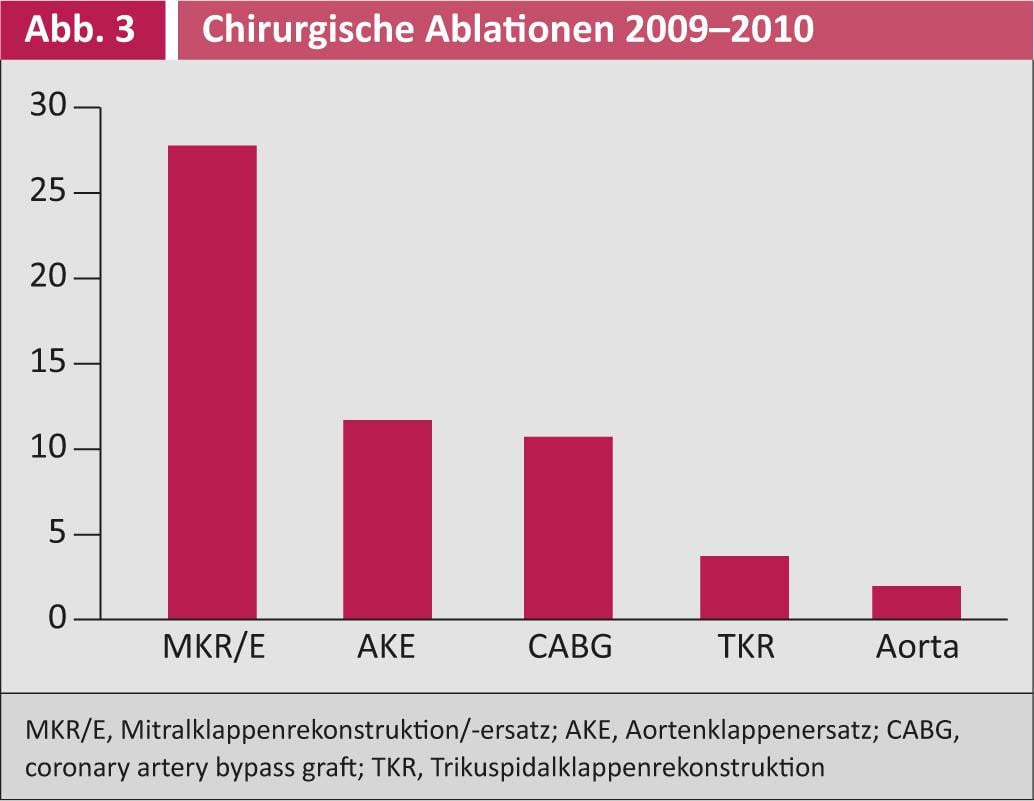

Figure 3 shows those operations that were combined with surgical ablation between 2009 and 2010. Surgical ablation was used in conjunction with mitral valve surgery in more than 25% of cases, followed by aortic valve and bypass surgery.

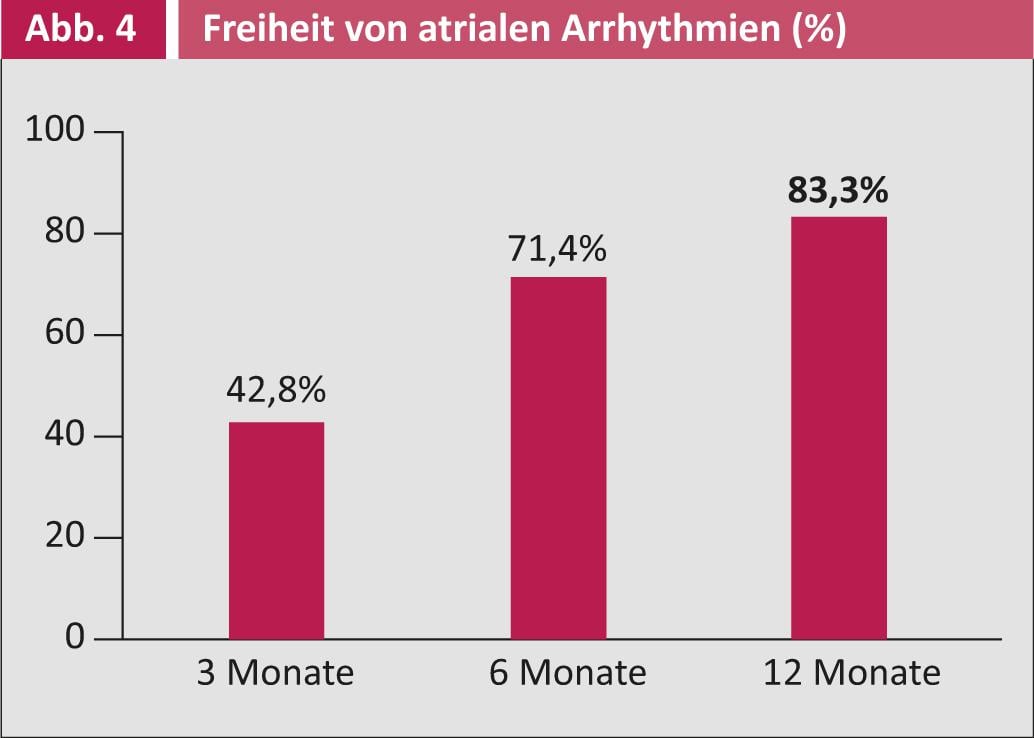

Figure 4 shows the respective success rates of surgical ablation: after three months, 43% of patients were free of VCF; after six months, the success rate even increases to 71%. After twelve months, 83% of patients were completely free of VCF.

The success of ablation also manifested itself in the fact that the use of antiarrhythmic drugs as well as anticoagulants was reduced or even eliminated after the operation. In this subanalysis, 85% of patients were no longer taking oral anticoagulants after 1 year, and 69% were able to discontinue class I and III antiarrhythmic medications.

Complications: Complications occurred postoperatively in 5 (12%) patients: Two patients suffered a cerebrovascular insult. One of them had an off left atrial ear, the other patient had an intact atrial ear. Both were under anticoagulation preoperatively as well as postoperatively.

Pericardial tamponade occurred during the course of one patient who was on anticoagulation, but it was successfully treated surgically. Further, one patient suffered ventricular tachycardia with cardiac arrest, after which successful electrical cardioversion was performed and an ICD was inserted. Another patient required a definitive pacemaker postoperatively (total pacemaker implantations postoperatively 4.7%).

Sinus rhythm or atrial paced rhythm at the end of surgery (p=0.001) and short duration of surgery (p=0.02) have previously been identified as positive predictors of freedom from VCF one year postoperatively.

Discussion: The question arises whether a continuous implantable “loop” ECG recorder-(Reveal) would offer even more accurate and continuous monitoring of cardiac rhythm. The devices that are currently available currently offer limited endurance, high sensitivity but reduced specificity, and are still very expensive. Further, it is unclear how such continuous recording with an implanted device affects patient compliance.

Conclusion

Surgical radiofrequency ablation for the treatment of VCF as a combined intervention during other cardiac operations offers a successful and safe procedure. Repeated and extended (at least 7-day ECG with event recording) monitoring of patients postoperatively allows detection of up to 13% cases suffering from still asymptomatic postoperative episodes of atrial fibrillation. These are often missed with a snapshot such as that provided by a simple ECG or even a 24-hour Holter ECG. This has a significant implication for the postoperative management of patients in terms of anticoagulation and antiarrhythmic medication settings. Certainly, it is useful for centers wishing to offer surgical therapy for VCF to design a similar longitudinal algorithm. It plays an important role in evaluating outcomes, but also stimulates the immensely important interdisciplinary collaboration between surgeons and electrophysiologists. Ultimately, it is the patients who benefit.

Literature list at the publisher

PD Alberto Weber, MD

PD Hildegard Tanner, MD

Prof. Dr. med. Thierry Carrel