At the EULAR Congress in Madrid, pain management took a central place. Prof. David Walsh, MD, Nothingham, focused on the special circumstances of patients with rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. One of his special concerns was to remind physicians of the psychosocial component in addition to drug therapy.

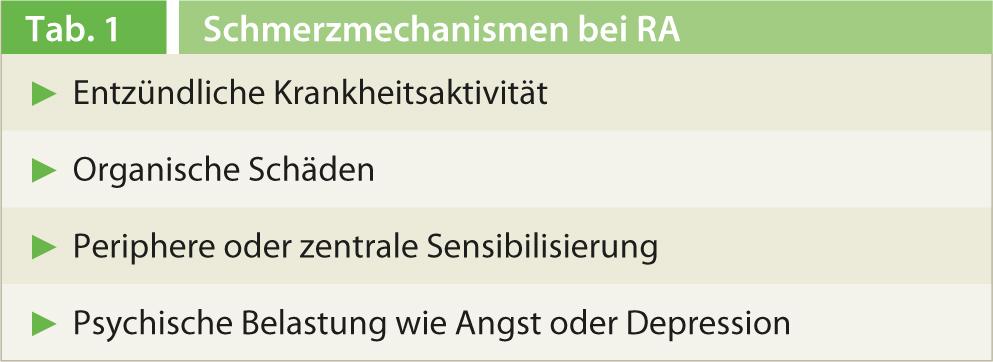

What is pain actually? Prof. David Walsh, MD, Director at the Arthritis Research UK Pain Centre, Nothingham, addressed the famous IASP (“International Association for the Study of Pain”) definition of pain in Madrid: “Pain is an unpleasant sensory or emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described by affected individuals as if such tissue damage were the cause” [1], making it clear that for patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in particular, pain is the symptom that causes them the most difficulty. Pain in RA is classified into different mechanisms(Table 1).

Following on from this, Prof. Walsh presented a mechanism-based biopsychological model of arthritis pain conditions. Consequently, the three dimensions of joint pathology, sensitization and vulnerability mesh like cogs and shape the patient’s respective individual pain picture. While joint pathology includes nociceptive factors such as inflammation and biomechanical features, vulnerability includes the context of the patient himself, which should not be underestimated. Examples include health or social security status, the genetic factors that influence the perception of pain, or comorbidities of the affected person. Also in this category, according to Prof. Walsh, is the psychological component of pain such as beliefs, expectations, anxiety, or even depression. It is precisely these influences that are too often disregarded or insufficiently included in therapy.

Pain is also a key component of osteoarthritis (OA). For example, one 65-year-old patient with OA in her knee had a problem primarily with never being able to predict when the pain would occur, how severe it would be, and how far her legs would take her this time. This resulted in frustration and insecurity on the part of those affected, which is difficult to deal with in everyday life. Further, Prof. Walsh indicated that according to Moreton et al. [2], the recording of pain intensity in OA according to the ICOAP pain scale (“Intermittent and Constant OA Pain Scale”) was suboptimal. Although the classifications of “pain that comes and goes” and “constant pain” correlate with the Rasch model, it cannot be said that total pain is the sum of constant and intermittent pain. Thus, the various dimensions of pain do not add up to total pain severity because, taken together, they no longer correlate with the Rasch model.

Successfully combat pain

Basically, various analgesics in RA relieve pain, improve sleep, ADL (activity of daily living), social activities, and medication satisfaction. In addition, analgesics are usually very well tolerated. However, he said, there are few high-quality studies on the effectiveness of analgesics in RA because existing studies often have a short observation period or small study populations. “There is certainly a need for further research here,” Prof. Walsh said.

Specifically, the following factors should be considered in the pain management of RA:

- Delayed administration of disease-controlling drugs (DMARDs) is associated with more pain at 12 months.

- Pain-reducing combination therapies are superior to monotherapies.

- If the disease remains active despite treatment with conventional DMARDs, administration of a biologic improves pain.

- The combination of anti-TNF with methotrexate was superior to administration of an anti-TNF drug alone in terms of pain relief.

- The opioids codeine, tramadol, and morphine have all been studied in short-term studies in RA (<6 weeks). The overall result showed clinical benefit in 54% of cases compared to only 38% on placebo (RR 1.41; p<0.02).

The treatment of osteoarthritis draws on both systemically or locally applied drugs and concepts from the fields of physical therapy or physiotherapy. Prof. Walsh advised preventive or early-stage OA to educate and inform patients, as well as strengthening exercises, aerobic fitness training as well as weight loss for obesity. Primary uses are acetaminophen and topical NSAIDs. Furthermore, opioids, oral NSAIDs/coxibs, intra-articular steroids, topical capsaicin therapy, as well as local treatment with cold and heat, manual therapy, shock-absorbing footwear, TENS (transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation) may be used in individual cases or as needed.

The question of whether NSAIDs are generally better taken regularly or as needed cannot be answered conclusively. The main problem is that although there are clinical trials on the efficacy of regular treatment in RA, there are no controlled trials that directly compare regular versus as-needed use of NSAIDs. Only one study in ankylosing spondylitis was conducted, but the differences in the treatment groups were not significant; regular use alone showed a worse mood state [3].

Context matters

Due to the complexity of the topic, the instructions for physicians are clear in that patients are not the same, but different and consequently require differentiated and individualized therapy. Context in particular is a factor that should not be underestimated. While the pharmacological effect size of pain relief in OA is 43%, contextual factors are one and a half times more significant with 67% effect size.

In summary, Prof. Walsh reiterated that pain in RA is characterized by complex mechanisms and consequently requires integrated solutions. Furthermore, Prof. Walsh is convinced that a pain assessment involves more than just the VAS score (“Visual Analogue Scale”) and drug treatment. The placebo effect should also be mentioned here, it is still more effective than no treatment at all.

Prof. Walsh offered an important final tip for all practitioners: “It’s certainly very useful to look at the different medical guidelines that use the same therapeutic tools.” He said this clearly shows the different perspectives of the disciplines and thus provides a comprehensive view of the therapeutic tools in question.

Source: How to Treat/Manage Session 4 at EULAR (Annual European Congress of Rheumatology), June 12-15, 2013, Madrid.

Literature:

- International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP): Definition of pain. www.iasp-pain.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=General_Resource_Links& Template=/CM/HTMLDisplay.cfm&ContentID=3058.

- Moreton BJ, et al: Rasch analysis of the intermittent and constant osteoarthritis pain (ICOAP) scale. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2012; 20: 1109-1115.

- Wanders A, et al: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs reduce radiographic progression in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a randomized controlled trial.Arthritis Rheum 2005; 52: 1756-1765.