Genetic predisposition, an impaired epidermal barrier with altered microbiome, and aberrant immune responses with type 2 inflammation are associated with the occurrence and activity of atopic dermatitis. Various provoking factors due to environmental influences trigger the disease process.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory disease that affects 15-20% of children and 1-3% of adults [1]. The clinical presentation of AD is characterized by dry and inflamed skin with scaling and/or weeping eczema on different parts of the body. The primary leading symptoms are pruritus and eczematous lesions. Predilection sites of atopic eczema in adults are the large flexures, although the skin lesions may also occur on other parts of the body such as the hands or face. In children, eczema tends to appear on the flexor sides of the arms and legs, as well as the wrists and ankles, and in infants, the face, scalp, and extensor sides of the limbs are most commonly affected. About half of those affected in childhood continue to suffer from atopic eczema in adulthood.

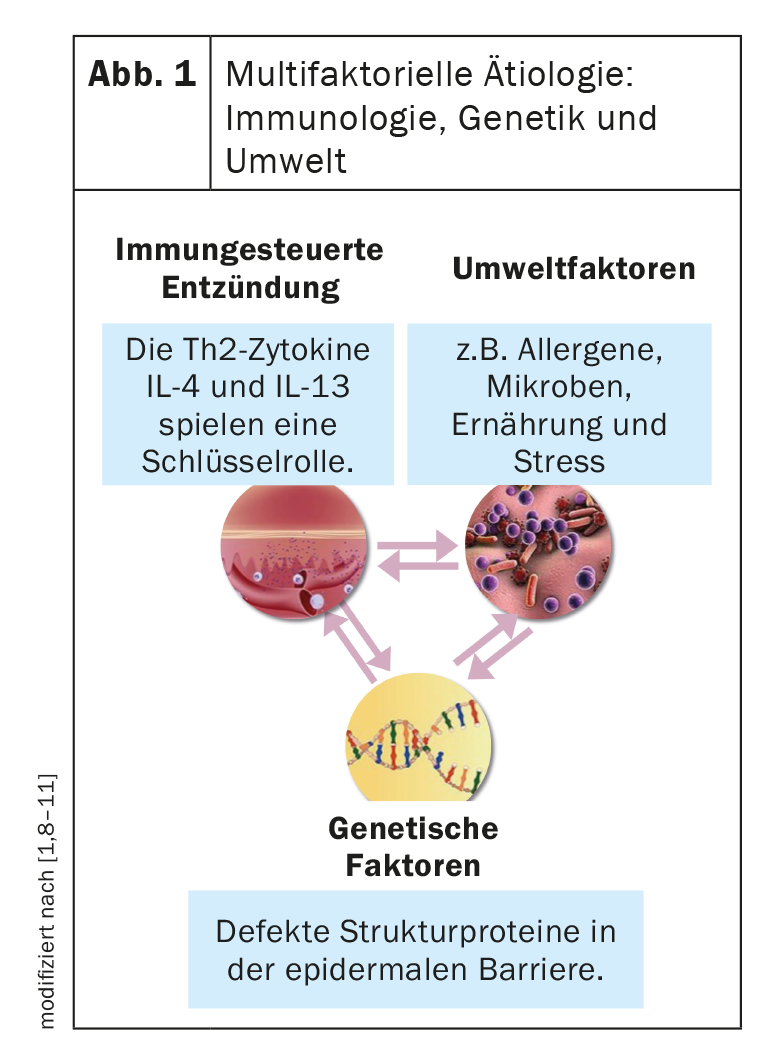

As is known today, AD is a multifactorial disease (Fig. 1) . In addition to dysregulated immunological processes, genetic factors (especially defective structural proteins in the epidermal barrier) and environmental factors play a pathophysiologically relevant role [4–7].

Complex interaction structure with dominant Th2 immune response.

The T helper cells (Th2 cells) are significantly involved in the pathophysiological process. In AD and other atopic diseases, Th2 cells produce inflammatory cytokines and coordinate immune responses. As a result of misregulation of Th2 cytokines, inflamed, highly pruritic lesions develop [2,3]. Since the interleukins IL-4 and IL-13 are also produced by other cell types, they are nowadays also referred to as type 2 cytokines** [2,3].

**Type 2 cytokinesand chemokines are produced by Th2 cells, ILC2 cells, eosinophils, mast cells, basophils, and macrophages.

Often associated with other atopic diseases

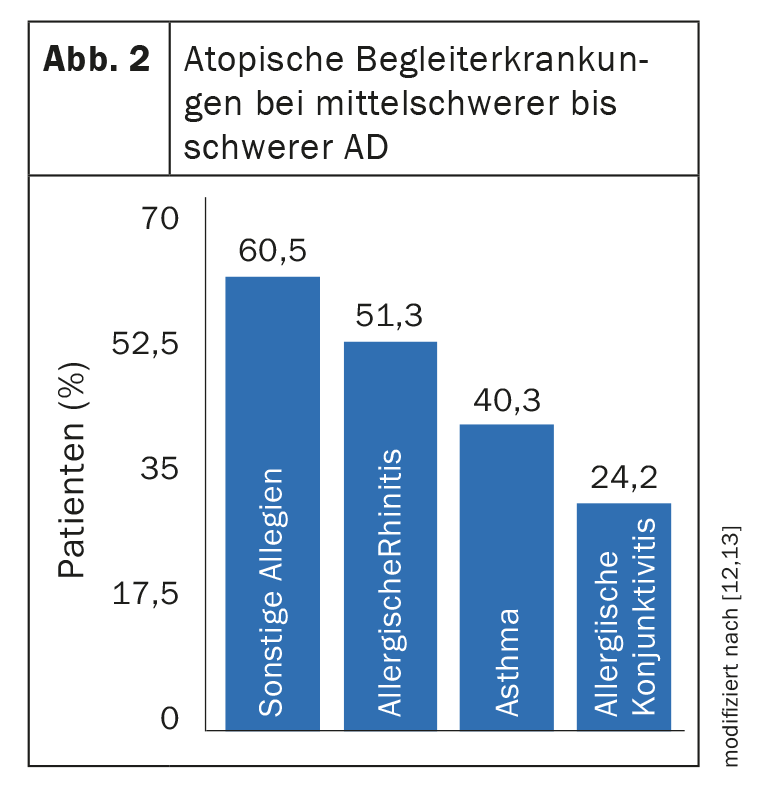

58-79% of all adult AD patients suffer from at least one other atopic disease regardless of severity (Fig. 2) [14–16]. The tendency for AD to begin in early childhood and develop over the lifespan food allergy, asthma, and allergic rhinitis is referred to as the “atopic march” [12,19]. However, the manifestation forms and course types of AD are very heterogeneous. Thus, there are patients who have no atopic comorbidities, those with a classic “atopic march,” or patients with persistent AD and either asthmatic symptoms or rhinitis as a late manifestation [12,19]. In addition, AD patients have an increased susceptibility to viral infections and there is evidence of associations with other pathologies. Severe manifestations of AD, in particular, can severely impact quality of life. Excruciating itching can lead to sleep disturbances, and the risk for depression and anxiety disorders is significantly increased compared to skin healthy individuals [17]. Study data show that improvement in skin symptoms is often associated with relief of concomitant conditions, including psychological symptoms [18].

Literature:

- “Atopic dermatitis, what’s new?”, Univ.-Prof. Dr. Paul-Gunther Sator, DermAlpin Salzburg, 30.10.2021.

- Akdis CA, et al: Allergy 2020; 75(7): 1582-1605.

- Nguyen JK, et al: Arch Dermatol Res 2020; 312(2): 81-92.

- Leung DYM, Guttman-Yassky E: JACI 2014; 134: 769-779.

- Hoffjan S, Stemmer S: Arch Dermatol Res 2015; 307: 659-670.

- Darsow U, et al: JEADV 2010; 24: 317-328.

- Williams MR, Gallo RL: Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2015; 15: 65.

- Lauffer F, Biedermann T: Dtsch Arztebl 2021; 118(24): 24.

- DHA, www.dha-neurodermitis.de/therapie/grundlagen-der-therapie.html, (last accessed, Jan. 06, 2023).

- Severity scoring of atopic dermatitis: the SCORAD index. Dermatology 1993; 186(1): 23-31.

- Nygaard U, Deleuran M, Vestergaard C: Dermatology 2017; 233: 333-343.

- Brunner PM, et al: J Invest Dermatol 2017; 137: 18-25.

- Silverberg JI: Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2019; 123(2): 144-151.

- Weidinger S, et al: Nat Rev Dis Primers 2018; 4(1): 2.

- Chiesa Fuxench ZC, Ong P: Poster presented at AAD 2018. Poster 6236.

- Drucker AM, et al: J Invest Dermatol 2017; 137(1): 26-30.

- Ronnstad ATM, et al: JAAD 2018; 79: 448-456.

- Reich K, et al: International Society of Atopic Dermatitis 2021.

- Belgrave DCM, et al: Curr Dermatol Rep 2015; 4: 221-227.

- Hill DA, et al: J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018; 6: 1528-1533.

DERMATOLOGY PRACTICE 2023; 33(1): 25