Today, there are several treatment options that have been shown to improve disease and symptom control in vitiligo. However, there appear to be certain gaps in treatment in everyday clinical practice. For example, a British study with data from over 17,000 patients showed that although topical corticosteroids (TCS) are used as first-line therapy in the majority of cases, as recommended by the guidelines, it takes a median of three years after a vitiligo diagnosis before the first vitiligo-specific treatment is given.

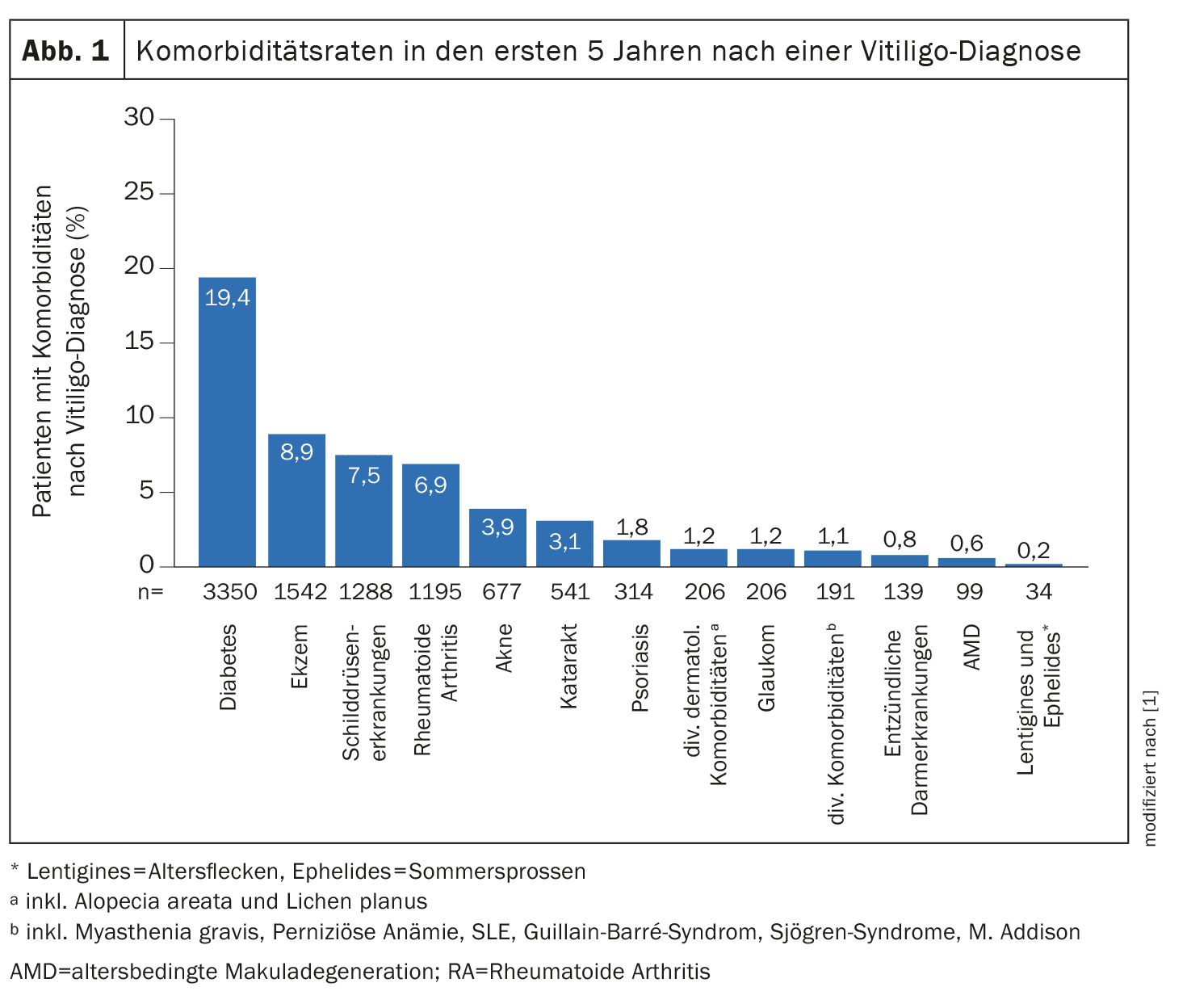

Vitiligo is a chronic autoimmune disease characterized by a loss of melanocytes, resulting in circumscribed depigmented skin areas of varying size. The prevalence of diagnosed cases of vitiligo in Europe is estimated to be between 0.2% and 0.8%. Those affected have a significant disease burden – vitiligo can have a profound impact on quality of life and is associated with other autoimmune diseases and the increased incidence of mental disorders. Eleftheriadou et al. retrospectively analyzed the data of 17,239 vitiligo patients [1]. For their analyses, the researchers used data that had been routinely recorded and archived in everyday practice in the UK as part of the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD), which was linked to the Hospital Episode Statistics (HES ). In total, CPRD Aurum contains data from around 40 million patients recorded since 1995. The incidence cohort of the present study included patients who were ≥12 years old at the time of the first vitiligo diagnosis. The entire study period was from January 1, 2010 to December 31, 2021, and the mean vitiligo incidence over this period was 0.16 per 1000 person-years. The most common comorbidities occurring after vitiligo diagnosis were diabetes (19.4%), eczema (8.9%), thyroid disease (7.5%) and rheumatoid arthritis (6.9%) (Fig. 1) [1].

One in four people suffer from depression or anxiety

The most common psychological comorbidities recorded at any time in the incidence cohort were depressive disorders (18.5%) and anxiety (16.0%), with depression and/or anxiety recorded in 24.6% of patients. Sleep disturbance and suicidality were reported at some point by 12.7% and 7.1% of patients, respectively, including 3.9% and 3.2% of patients newly diagnosed with vitiligo. In the first year after vitiligo diagnosis, 16.7% of patients were prescribed antidepressants and/or anxiolytics; prescription rates remained relatively stable in each of the five years after diagnosis.

Starting treatment early could reduce the burden of disease

In the first year after diagnosis, 60.8% of the 16 741 patients whose data were linked to the outpatient HES database had no record of vitiligo-related treatments, which increased to ≥82.0% from the second year onwards. Of the patients whose data were linked to the HES, 29.1% received a prescription for topical corticosteroids (TCS) in the first year, 11.8% were prescribed topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCI) and 4.2% were prescribed oral corticosteroids (OCS). From the second year onwards, the percentage of patients prescribed OCS remained stable, while the prescription of TCS and TCI decreased to 11.4% and 3.9% respectively in the second year and remained low thereafter. The median duration from diagnosis to the first record of vitiligo-related treatment was 34.0 months (95% confidence interval [KI] 31.6-36.4) months. After 1 year, 40.1% had undergone their first vitiligo treatment. The study authors state that inadequate use of effective therapies contributes to the high disease burden of vitiligo patients. And they point out that new, effective treatments and early treatment initiation in combination with psychological measures are needed to reduce the disease burden in patients with vitiligo [1].

What do current guidelines recommend?

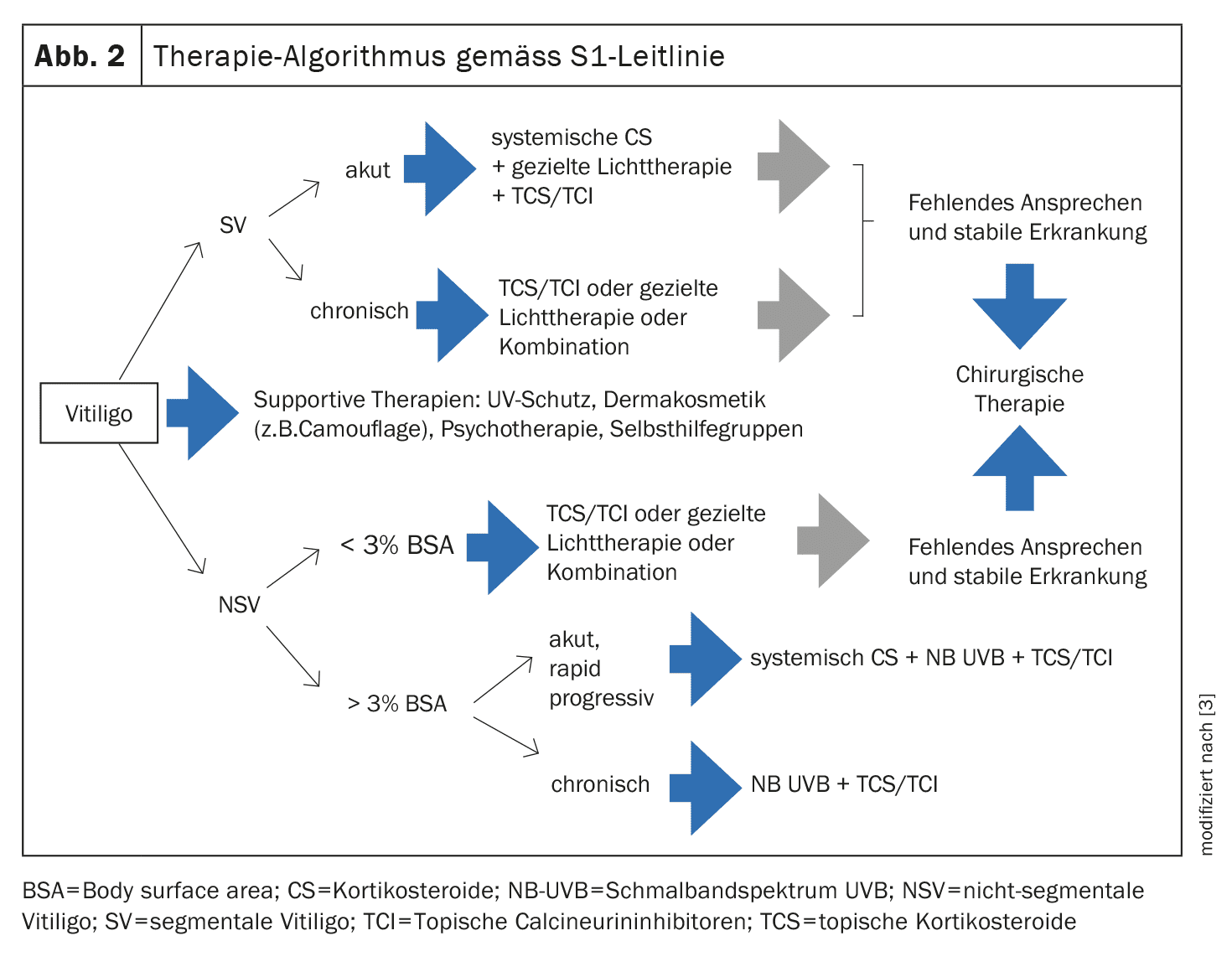

Both the British guidelines and the German S1 guideline advocate early adequate intervention in vitiligo in order to reduce the disease burden [2,3]. A simplified treatment algorithm of the German guideline is shown in Figure 2. Below are some explanations of the individual treatment options.

TCS as “first-line” therapy: According to the German S1 guideline from 2022, the use of topical corticosteroids (TCS) is the therapy of first choice for limited vitiligo (infestation of <3% of the body surface) and extrafacial infestation [3]. Potent corticosteroids (class III) with an improved therapeutic index such as mometasone furoate are recommended, for example over a period of 3 months (once a day) or 6 months (once a day for 15 days followed by a 14-day break). This therapy is also suitable for children, although systemic resorption in intertriginous areas must be taken into account.

TCI as “second-line” therapy: Topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCI) can be used as an alternative to TCS [3]. Their advantage lies in their safety for long-term use, as they do not cause skin atrophy with prolonged use compared to TCS. The efficacy in the face and neck area is comparable to that of TCS. It is recommended to apply TCI twice a day for 6-12 months, depending on the response. If repigmentation is successful (even after phototherapy and targeted light therapy), proactive therapy with TCI applied twice a week reduces the risk of recurrence.

Phototherapy: Another important treatment modality is phototherapy. Nowadays, narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) is primarily used for this purpose [3]. Usually, a discrete erythematogenic dose is administered two to three times a week over a period of several months. An alternative to light therapy in outpatient clinics or specialist practices is NB-UVB home therapy, for which various devices (hand-held, partial-body and whole-body irradiation systems) are available [4]. According to the guideline, temporary whole-body phototherapy can be used not only for repigmentation but also to prevent disease progression. The data on the effects of the combined use of phototherapy with external or systemic therapies is inconsistent.

Other therapy methods: Numerous studies underline the effect of the 308 nm excimer laser or lamp on vitiligo [3]. The effect of systemically administered corticosteroids and other immunosuppressants has been described in vitiligo in the form of individual reports and small case series. Oral mini-pulse therapy with corticosteroids (e.g. dexamethasone, prednisone or methylprednisolone) on two consecutive days per week can be considered in acute, rapidly progressive vitiligo. The duration of therapy is 3-6 months, with mild to moderate cortisone side effects frequently occurring. Surgical treatment options are among the most effective interventions for stable vitiligo, with the following techniques generally available: Tissue grafts using full-thickness skin grafting, split-thickness (ultra-thin) skin grafting or suction blister technique and cell transplantation of autologous cultured or non-cultured epidermal melanocytes [7].

Which new therapeutic approaches are promising?

Topical or systemic Janus kinase inhibitors (JAK-i) hold great promise [3]. A promising cream with the active ingredient ruxolitinib has been approved in the EU since 2023; there is currently no approval in Switzerland (status of information: 03.10.2024) [5]. This was developed for the local treatment of non-segmental vitiligo in adults and children aged 12 and over. There is a γ-IFN signature of various inflammatory cells in the skin of vitiligo. The γ-IFN-mediated signal transduction proceeds via the activation of JAK, which are expressed in a cell-specific manner. These kinases can be blocked subtype-specifically by JAK-i [3]. The efficacy of topical ruxolitinib at different concentrations (0.15-1.5%, once or twice a day) was investigated in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) in 157 patients versus a vehicle preparation [6]. Patients with non-segmental vitiligo were included regardless of disease activity and disease duration. With ruxolitinib 1.5% (once daily), 50% achieved significant changes in the facial VASI50 (F-VASI) after 24 weeks in the verum arm compared to 3% with placebo. Itching at the application site was the most common adverse effect of ruxolitinib cream [6].

Literature:

- Eleftheriadou V, et al: Burden of disease and treatment patterns in patients with vitiligo: findings from a national longitudinal retrospective study in the UK. Br J Dermatol 2024; 191(2): 216-224.

- Eleftheriadou V, et al: British Association of Dermatologists guidelines for the management of people with vitiligo 2021. Br J Dermatol 2022; 186: 18-29.

- Böhm M, et al: S1 guideline: Diagnosis and treatment of vitiligo. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2022; 20(3): 365-379.

- Eleftheriadou V, et al: Feasibility, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, multi-centre trial of hand-held NB-UVB phototherapy for the treatment of vitiligo at home (HI-Light trial: Home Intervention of Light therapy). Trials. 2014 Feb 8; 15: 51.

- European Medicines Agency (EMA): Opzelura, www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/opzelura,(last accessed 30.09.2024)

- Rosmarin D, et al: Ruxolitinib cream for treatment of vitiligo: a randomised, controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet 2020; 396: 110-120.

- van Geel N, Ongenae K, Naeyaert JM: Surgical techniques for vitiligo: a review. Dermatology 2001; 202: 162-166.

DERMATOLOGY PRACTICE 2024; 34(5): 44-45