Short-term administration of systemic corticosteroids (SCS) is an effective and fast-acting option to resolve acute asthma symptoms, including exacerbations. Early administration of SCS to treat severe seizures is considered standard, and it is recommended that it be given to the patient within one hour. In practice, however, SCS are often prescribed over a longer period of time – but this can be associated with side effects.

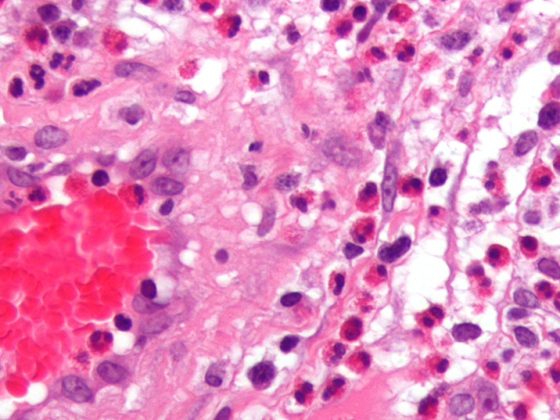

SCS have an anti-inflammatory effect by inhibiting the production of pro-inflammatory mediators and reducing the chemotaxis of inflammatory cells in the lung. However, probably because of their efficacy, relative affordability, or the impression that short administrations are harmless, substantial overprescribing of SCS has been reported in both adults and children with asthma, write Prof. David Price of the Observational and Pragmatic Research Institute, Singapore, and colleagues [1]. The Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) recommends SCS for short-term treatment, usually 5-7 days, of severe acute exacerbations.

Patients with asthma often take SCS in addition to moderate- or high-dose ICS and sometimes nasal corticosteroids, all of which are known to have systemic bioavailability. Cumulative side effects of ICS use have been documented; therefore, patients taking both ICS and SCS may be at additional risk for steroid-related side effects. The researchers refer to a systematic review and meta-analysis whose authors found that the SCS-sparing effect of high-dose ICS was mainly due to systemic effects. They speculate that 1000 µg of fluticasone propionate has similar systemic effects to 5 mg of prednisone and that 2500 µg of budesonide has similar systemic effects to 5 mg of prednisone. It has been suggested that high doses of ICS should possibly be considered as harmful as low doses of SCS.

Type 2 diabetes common side effect

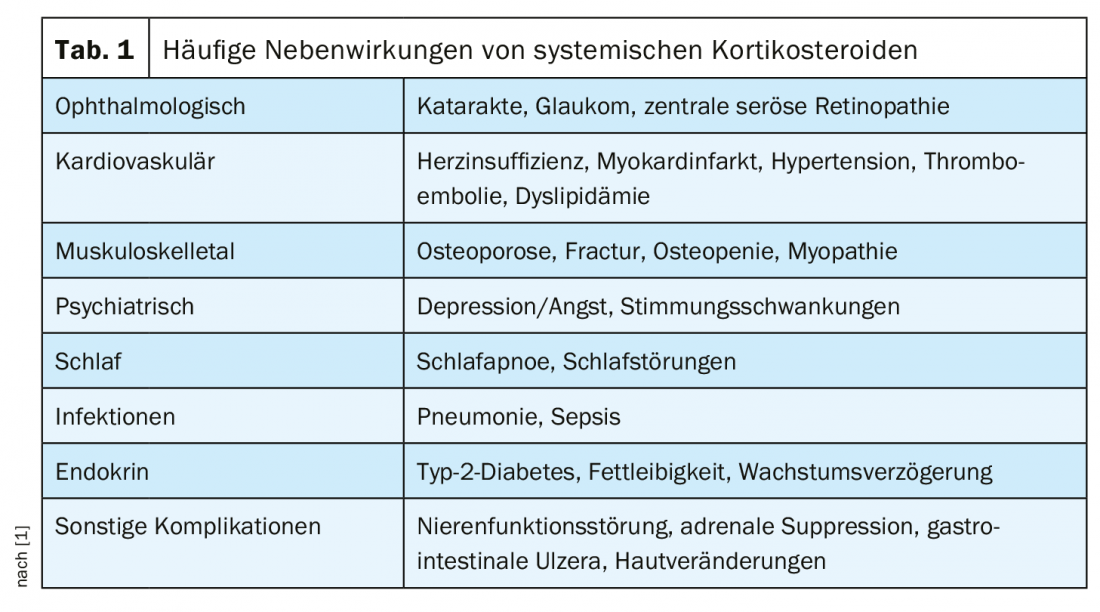

The most common serious comorbidities associated with long-term SCS administration include osteoporosis and osteopenia, type 2 diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular disease. In addition, SCS use has been associated with psychiatric symptoms such as insomnia, anxiety or aggressive behavior, dyspeptic disorder, hypertension, and dyslipidemia (Table 1). The dose-response relationship for cumulative SCS exposure with the most adverse events began in a recent study at cumulative exposures of 1 g to <2.5 g and for some outcomes at cumulative exposures as low as 0.5 g to <1 g.

The occurrence of type 2 diabetes is one of the most common adverse events associated with SCS administration, and there is evidence of a cumulative effect of increased exposure. Patients with asthma who received an average daily SCS dose of ≥7.5 mg/day had a 15-year cumulative incidence of type 2 diabetes (37.5%) that was five times higher than in patients who received <0.5 mg/day. Even three steroid bursts per year lead to an increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes in the long term, the authors write. For example, other studies have shown a substantial effect of short-term SCS on mood change in asthma patients: After only 3-7 days of prednisone therapy, significantly increased symptoms of mania and mood changes were reported by both physicians and patients. Similarly, 8 days of SCS therapy caused organic mood disorder in patients with ocular complaints; hypomania occurred in about 30% of patients and depressive syndrome in 10-12%.

Limitation of cumulative dose to 1 g/year

There are risks associated with both short-term intermittent use of SCS and longer-term use. A recent report estimated that 93% of patients with severe asthma had at least one condition related to SCS exposure. This includes morbidity and especially mortality. Regular use of SCS is associated with higher all-cause mortality compared with non-SCS use [1].

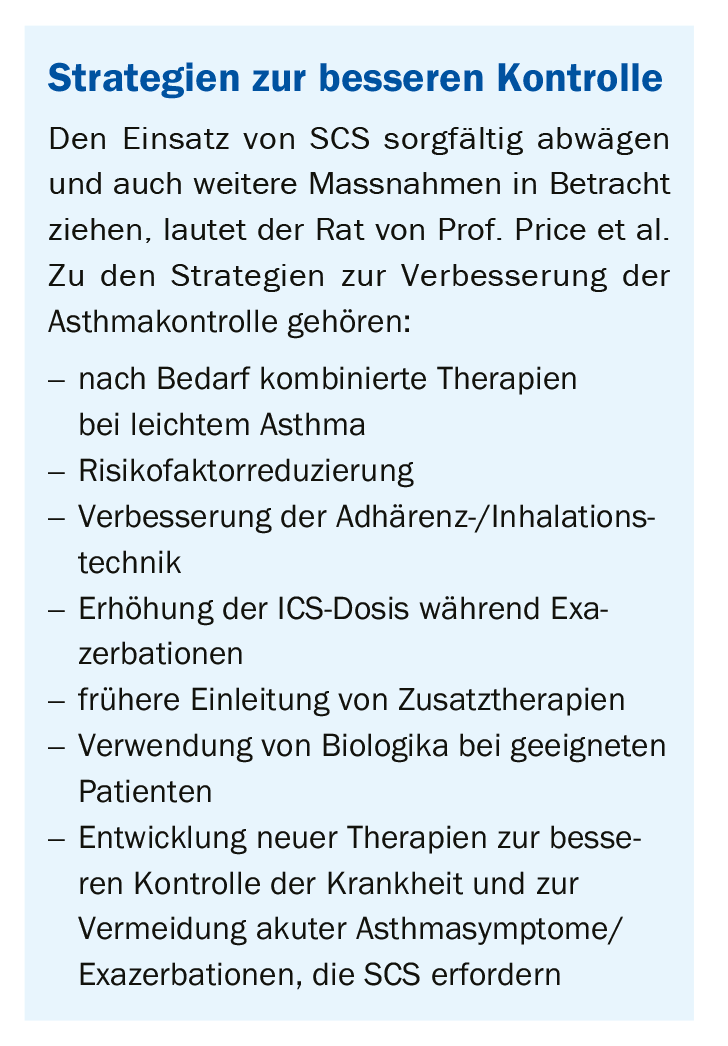

Although the benefits of short courses of SCS outweigh the risks in patients with acute asthma, these therapies are not warranted in all patients, Prof. Price and his colleagues conclude. The improvements in asthma symptoms achieved by SCS, even in short courses, would have to be weighed against the side effects of this therapy. They therefore suggest that awareness of the potentially harmful effects of SCS, regardless of dose, duration, or frequency of administration, needs to be further raised among health professionals. A cumulative dose of 1 g per year could be considered as an easily retrievable threshold, he said. This is equivalent to four short SCS administrations at the usual doses used to treat an asthma exacerbation, and studies would have shown that the prevalence of many corticosteroid-induced comorbidities is increased at doses above this level. Because patients with asthma may also be prescribed SCS for the treatment of nasal polyps, rhinosinusitis, or other comorbidities, the authors recommend the threshold of 1 g per year as the total dose that should include the prescription of SCS for each indication.

SCS yes, but with caution!

In suitable patients, SCS are a very effective therapeutic option for the treatment of acute asthma exacerbations, but inappropriate use must be avoided, the researchers concluded. Finding this balance between efficacy and safety is of utmost importance, he said. Otherwise, asthma patients carry not only the disease but also the steroid-related morbidities. The results of the studies reviewed suggest that even very short dosing periods (3-7 days) of SCS are sufficient to produce significant adverse outcomes in patients. Inappropriate short-term use of SCS to treat mild exacerbations or symptoms of asthma should therefore be considered a significant health problem that needs to be addressed through education.

Literature:

- Price D, Castro M, Bourdin A, et al: European Respiratory Review 2020; 29: 190151; doi: 10.1183/16000617.0151-2019.

InFo PNEUMOLOGY & ALLERGOLOGY 2020; 2(3): 39-40.