Overuse injuries in sports are etiologically diverse. Their treatment requires the inclusion of diverse intrinsic and extrinsic factors. An insight into the causes and manifestations of this most common type of sports injury – and how to treat it.

In addition to the health-promoting effects of regular, sensibly practiced physical activity, sport also has a downside: sport-related accidents and overuse injuries. While the number of sports accidents is statistically reasonably well recorded (UVG: 300,000/year*, BfU: 410,000/year), overuse injuries are hardly quantifiable, as they are administered via the health insurance companies and thus not reported. However, our own statistics, collected over five years, showed that overuse injuries are more than twice as common as injuries [1].

How does overload occur?

In order to understand the concept of overload damage in sports, it is necessary to recall the basic principles of training theory (correct loading and recovery cause positive adaptation of the stimulated structure) and to review adaptation performances of the types of tissues of the musculoskeletal system (Tab. 1).

However, in the context of athletic use, it often happens that these basic principles are not respected – on the contrary: training is done under full load, especially in amateur sports, without taking into account extrinsic factors such as training planning, recovery, nutrition, equipment (sports shoes, tennis racket grip circumference, wheel mass, etc.), sports technique and choice of ground. If, in addition to unfavorable extrinsic factors, intrinsic as well as obstructive anatomical shape variants (bent, flat and splay foot, bow or knock-knees, hip rotation, hyperlordosis, elbow valgus, etc.) and further aspects such as bone density disorder or growth are added, it is understandable that body parts suffer damage. Perhaps the most illustrative example of an overload reaction is the fatigue or stress fracture of the II Os Metatarsale: the rearfoot load is equivalent to 1.2 times the body weight for each step, and 2.4 times for leisurely jogging. For a 70 kg person who takes 8000 to 10,000 steps (the lower limit for a health-promoting effect), his feet have borne a load of 2.52 tons at the end of the day, and 858,480 tons at the end of the year. With such loads it is not surprising that a small, long foot bone “gives up”, even more so if the footwear and thus the foot statics are suboptimal.

Manifestations of sports overload

The sport-related overload damage is a reversible, sometimes irreversible damage of a structure mainly of the musculoskeletal system, caused by a disproportion between load and load capacity of the respective body part as well as favored by various factors of intrinsic and extrinsic nature. The imbalance only manifests itself after a certain time. Table 2 provides information on possible overload reactions of the different tissue types.

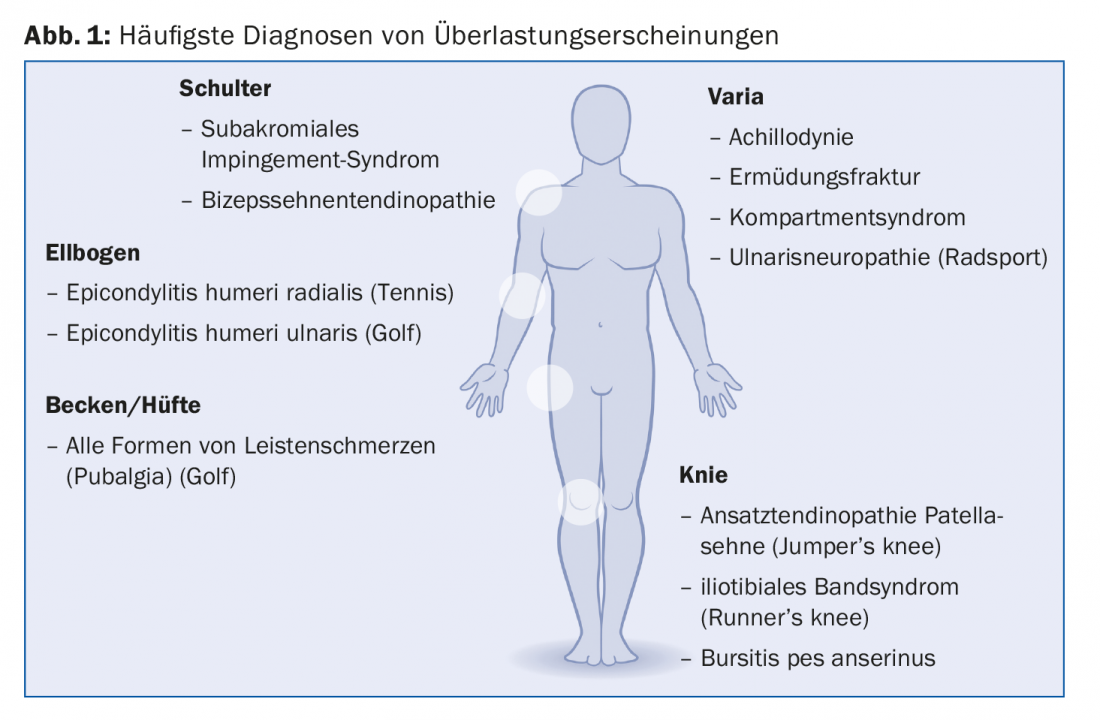

Stress reactions at the bone are painful conditions with periosteal reaction but without cortical continuity breaks. It is found on the inner edge of the tibia. The clinical presentation is known as medial tibial stress syndrome (MTSS). It is a preliminary stage in a continuum to a full stress fracture. The terms tendinopathy and tendinosis have replaced the term tendinitis. Tendon pathologies have been well studied scientifically, proving, among other things, that inflammatory factors are rarely found in painful tendons. Not only mechanical, but also metabolic factors are responsible for the change: for example, overweight and diabetic patients suffer more frequently from tendinopathies, with the “reactive oxygen species” (ROS) being attributed a central role. The concept of muscular imbalances – “shortening” (tonus increase) of tonic muscles and weakening of phasic ones – has been sufficiently disseminated by manual medicine. Enthesopathies affect both muscles and tendons. The topic of osteoarthritis and sports is very complex. In principle, sports do not increase the risk of osteoarthritis, provided the joints are healthy. However, sports promote many joint injuries, which can subsequently act as a door opener to (pre)osteoarthritis. Bursitis is found at anatomic sites where overstretched muscles and their tendons mechanically irritate protective structures. Examples include iliotibial band syndrome and ulnar nerve neuropathy, which is caused in cyclists by the shock of the handlebars. Figure 1 summarizes some of the most common diagnoses of overload. Only diagnoses occurring in adults were intentionally mentioned. In the adolescent, all growth osteochondroses (Osgood Schlatter, Sinding Larsen, Sever, etc.) can be considered overload pathologies.

Clinical aspect

In consultation, most patients complain of strain-related pain. This can be derived from Blazina et al. [2] into four different stages:

- Pain only at the beginning of the activity

- Pain at the beginning and at the end of the activity

- Increasing pain during the sports program

- Permanent pain of variable intensity even at rest

This classification only provides information about the severity of the overuse injury. It hardly changes the therapy, which must be initiated in the first stage for a favorable prognosis.

During history taking, the patient is usually able to accurately point out the often pinpoint area of pain. Appropriate provocation tests (movements against resistance) are used to try to reproduce the pain. In some cases (bursitis, fatigue fractures, tendinopathies), swelling can be noted over the painful area, and redness is rather rare. In principle, no pathological values are found in the blood. Imaging is necessary when stress fractures are suspected, and MRI is the tool of choice. In most other sports-related overuse injuries, such technological clarifications are not mandatory. It would also be beneficial to have information, not always readily available in the consultation, about the technique used in the execution of the sport-specific gesture (backhand and forehand in tennis, handhold in javelin throwing, running style in the various running sports) and about the characteristics of the sports equipment (e.g. grip circumference and stringing strength of the tennis racket, sitting position on the bicycle, wear pattern of the soles of the shoes). Not infrequently, biomechanical gait analyses have proven useful. These clarification procedures are relatively easily available today.

Therapy

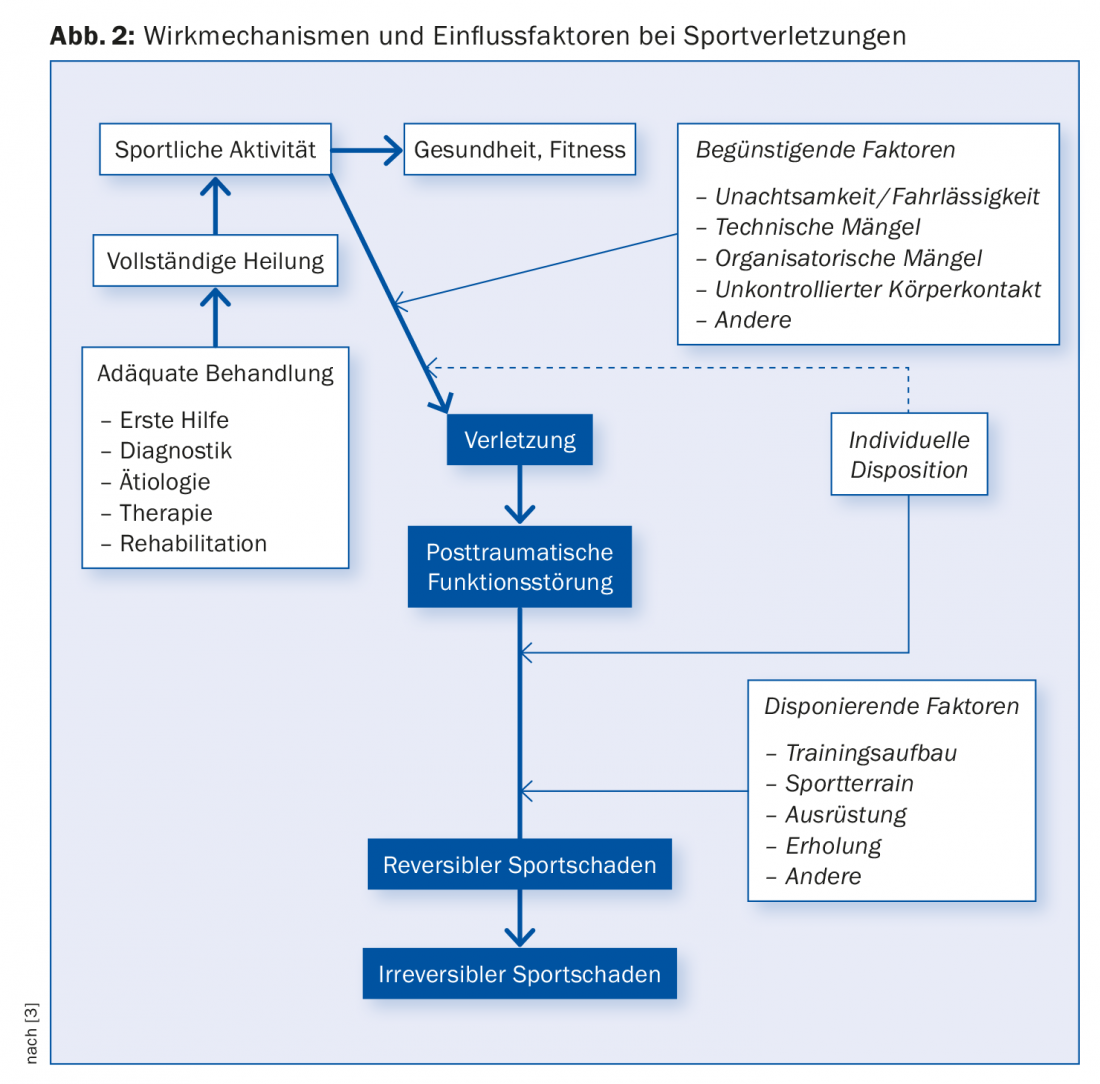

The therapy of an overload symptom in the musculoskeletal system of an athlete is an exciting, but also very demanding medical action due to complex mechanisms of action (Fig. 2). In particular, the treating physician should curb his possible desire to apply a cortisone injection “loco dolenti”. Local pain relief, which is fast and effective in the short term, will not change the causes of the problem at all, but will only accelerate the vicious circle: The momentary reduction in pain will cause the athlete to resume his longed-for activity quickly and comprehensively, but in a similar manner, and it will not be long before the disorder makes itself felt again, possibly aggravated. Practically, the first step is to stop the harmful stress; this alone can be a challenge for those who enjoy exercise. At the same time, a replacement program should be established, preferably with the help of the physiotherapist, who must necessarily be involved in the treatment. He can relieve local pain with mainly passive measures and at the same time strengthen muscles and tendons through specific training. Moreover, intrinsic and extrinsic factors must be addressed. This is also where it can be beneficial to involve the trainer in the healing process, as training errors often play a role. Thus, the treatment of overuse injuries is an endeavor that involves many factors with numerous participants and requires a high degree of sensitivity on the part of the sports physician.

* The data basis is formed by the employees in Switzerland who are compulsorily insured according to the Accident Insurance Act (UVG) as well as the unemployed. All other persons (children, schoolchildren, students, non-working housewives and househusbands, retired persons) are insured under the Health Insurance Act (KVG) and are therefore not included in the statistics.

Literature:

- Jenoure P: Talking statistics 2003.

- Blazina ME, Kerlan RK, Jobe FW: Jumper’s Knee. Orthop Clin North Am 1973; 4: 665-678.

- Jenoure P, Feinstein R, Segesser B: Prophylactic measures in sports injuries and sports damage. Austrian Journal of Sports Medicine 1987; 3: 7-10.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2018; 13(9): 8-10