In the treatment of esophageal cancer, it is necessary to pay attention to a sufficiently high caloric intake from the first day of treatment. In locally advanced esophageal cancer, neoadjuvant chemotherapy/radiotherapy (CROSS trial) has become well established. Surgical technique for esophageal cancer is not standardized internationally and needs further evaluation. Reconstruction of the esophagus is primarily performed by gastric elevation. The minimally invasive technique can be performed as an alternative to open resection. Salvage esophageal resection may be considered for locoregional recurrence of esophageal carcinoma treated by definitive CRT.

Esophageal cancer is a rare tumor with poor prognosis. According to the National Cancer Registry (NICER), 15 new cases (m/f, 11/4) per 100,000 population are diagnosed and 12 (m/f, 9/3) esophageal cancer-associated deaths per 100,000 population are recorded per year (2007-2011). Worldwide, squamous cell carcinoma dominates (70%) compared to adenocarcinoma (25%). However, in Western industrialized nations, adenocarcinomas are showing dominance and their incidence is now 60% in Switzerland. This appears to be associated with the change in risk behavior associated with Helicobacter eradication.

The individualized and multimodal therapeutic approach is nowadays considered standard. Every patient with esophageal cancer must be evaluated at a tumor board by an interdisciplinary team before therapy is initiated.

Staging, risk evaluation

In addition to endoscopy and histology, CT thorax/abdomen is essential in the staging of esophageal cancer. Endosonography is superior to all other methods in the differentiation of early T1, T2 carcinoma and is therefore mandatory. In adenocarcinomas of the esophagogastric junction (AEG), the classification according to Siewert is necessary not only with regard to prognosis but also, and above all, with regard to the therapeutic approach and must be demanded by the endoscopist. Since additional findings are made on PET-CT in 5-10% of cases, we consider it obligatory, especially in locally advanced tumors, making normal CT unnecessary. However, this has not yet found its way into the current guidelines. If the tumor is related to the tracheobronchial system, an additional bronchoscopy must be performed. In 10% of cases of squamous cell carcinoma, a second tumor is found in the ENT region, which is why an upper panendoscopy is indicated. Staging laparoscopy is recommended for distal adenocarcinomas to exclude peritoneal carcinomatosis and can additionally be readily used to insert a jejunal tube for nocturnal additive feeding.

The therapy of esophageal carcinoma – even if only by surgery alone – is full of complications and stressful, therefore a preoperative risk assessment with preoperative, functional clarifications and preparations as well as patient education is extremely important. Supplemental feeding and/or a feeding jejunostomy should be evaluated early and initiated as supportive measures, and the patient and family members should be made aware of and supported in the importance of adequate nutrition.

Therapeutic procedure

Early stages: endosonographic (uTm1, uTm2) carcinomas confined to the mucosa are nowadays clearly the domain of endoscopic therapy (endoscopic mucosal resection, EMR), as they practically do not metastasize lymphogenically, as shown by the retrospective data of Hölscher and his group [1]. If a deeper infiltration is found during the EMR (pTm3, pT1sm1-3), the further procedure can be planned with the help of these resects or the pT1sm1-3. extended biopsies can be substantiated and defined in terms of better staging. Overtreatment” is prevented. If the submucosa is reached, a lymphogenic metastasis risk of up to 43% can be expected and local treatment alone is certainly insufficient [2].

UT1sm1-3, uT2N0 carcinomas are operated directly, including adequate lymphnodectomy.

Locally advanced tumors: All patients with locally advanced tumors are nowadays pretreated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy/radiotherapy (CRT) before surgery after a therapy-free interval of six to eight weeks, with recent data suggesting waiting rather longer (up to twelve weeks). Taxane-based CRT (Cross Trial Group) has clearly prevailed and established itself as the standard. Neoadjuvant CRT vs surgery alone resulted in a statistically significant 3-year survival benefit of 59% vs 48% in this study, with a pathologically complete remission of 32.6%.

Operational management

Esophageal surgery is associated with a high complication rate (40-60%) and mortality rate (4-8%). Perioperative management requires routine and practiced cooperation between all specialists involved and the surgeon. The progress in the postoperative course is largely due to advances in intensive care medicine with improvements in analgesia, adapted fluid substitution, aspiration prophylaxis, etc., and standardized interdisciplinary collaboration. Thus, it is not surprising that here, too, the experience of a treatment team and thus the higher number of cases (>10 per year) leads to better results – as shown by various epidemiological studies. A recent European study [3] illustrates that a 30-day mortality rate of 1.9% (Sweden) is achievable. In esophageal surgery, however, these data need to be analyzed very closely, as quite a few patients survive complications for 30 days but then die in the hospital because they do not recover from further complications. That is why the 30-day mortality rate is of limited value. A hospital mortality rate would be much more transparent.

Surgery, lymphnodectomy

Various surgical techniques are used in esophageal surgery:

- transhiatal resections

- transthoracic resections (Ivor-Lewis) with an abdominal and thoracic phase and an intrathoracic anastomosis

- Thoracoabdomino-cervical resection (3-incision, McKeown-type) with cervical anastomosis.

The choice of resection procedure depends on several factors: the location of the tumor, the type of reconstruction planned, the patient’s pre-existing conditions, and last but not least, the surgeon’s preference and routine. Cervical anastomoses show much more frequent anastomotic stenoses (40-60%), which require recurrent bougienage postoperatively, compared to intrathoracic anastomoses (2-10%). Similarly, cervical anastomoses are associated with a higher rate of recurrent paresis (5-30%), which is virtually absent with intrathoracic anastomosis (<1%). The anastomotic insufficiency rate is lower for intrathoracic sutures (2-10 vs. 15- 30%), but very often associated with life-threatening sequelae such as mediastinitis and re-interventions. Cervical anastomotic insufficiency virtually always heals conservatively and is never life-threatening. Many retrospective studies have compared the different surgical techniques-with no significant difference. Only Hulscher et al. [4] showed better 5-year survival (39 vs. 27%) for transthoracic approach with adequate lymphnodectomy compared with transhiatal resection. This likely due to more extensive lymphnodectomy along the tracheobronchial system. Transhiatally, lymphnodectomy is really only successful as far as the inferior pulmonary vein – lymph node removal along the trachea and tracheal bifurcation and along the main bronchi is difficult. 23 Lymph nodes should be removed at the time of esophagectomy, as shown in an international study [2]. This can be a quality feature of an appropriate surgery. The German expert group (German Advanced Surgical Treatment Study Group) recommends radical esophagectomy with mediastinal and abdominal lymphnodectomy in the sense of a “two-field” lymphnodectomy [5]. “Three-field” lymphnodectomy, as often performed in Japan, is associated with higher morbidity (tracheostomy, lanryngeal nerve lesions) [5,6]. It tends to show a benefit in long-term survival in both proximal and mid-third esophageal carcinomas [7] and has found its way into Japanese guidelines. In Europe and America, however, “three-field” lymphnodectomy is performed only in selected centers in individual cases.

Reconstruction

Internationally, the gastric tube is the first choice for esophageal replacement. Alternatively, a colonic or ileocoecal interposition device can be chosen, which is retrosternally anastomosed to the cervical esophagus. A colonoscopy should be performed prior to colonic interposition. A colonic interposition device can cause fetal bad breath for the patient and thus significantly reduce the quality of life.

As a result of vagus resection and gastric tube formation, pylorospasm occurs in 20% of all patients, resulting in delayed gastric emptying. Surgically, various studies show no advantage to routinely performing pyloroplasty. This problem should be treated conservatively with prokinetics, nutritional adaptation, and dilatation of the pylorus if necessary, as experience has shown that it is limited to two to three months. In this situation, infiltration of the pylorus with Botox may be considered.

Minimally invasive esophagectomy

In the United Kingdom, of 7502 esophagectomies, 1155 (24.7%) are already performed using a minimally invasive procedure (2009-2010) [6]. Many single-center series, retrospective analyses, meta-analyses, and systemic reviews demonstrate that the minimally invasive technique is an alternative to the open technique. Equally good oncologic outcomes can be achieved, and some meta-analyses show a tendency for morbidity regarding anastomotic insufficiency and pulmonary complications to be slightly better in the minimally invasive group [6]. The first data of a multicenter randomized study from Holland demonstrate a clear advantage regarding early postoperative pulmonary complications in favor of the minimally invasive technique [8]. The Ivor-Lewis procedure with an anastomosis performed thoracoscopically is technically demanding and requires expertise with appropriate case numbers, as demonstrated by Luketich’s group [9].

Salvage esophagectomy

If locoregional recurrence or treatment failure occurs after definitive CRT, surgery may be considered as a treatment option, especially if R0 resection can be achieved. This is confirmed by data from 65 patients who underwent surgery after definitive CRT for distal adenocarcinoma at an average of 216 days. Postoperative morbidity, mortality, and long-term survival are similar to the group with planned neoadjuvant CRT and surgery [9]. Therefore, close follow-up after definitive CRT is indicated in order to offer patients with solitary locoregional recurrence another curative therapy option.

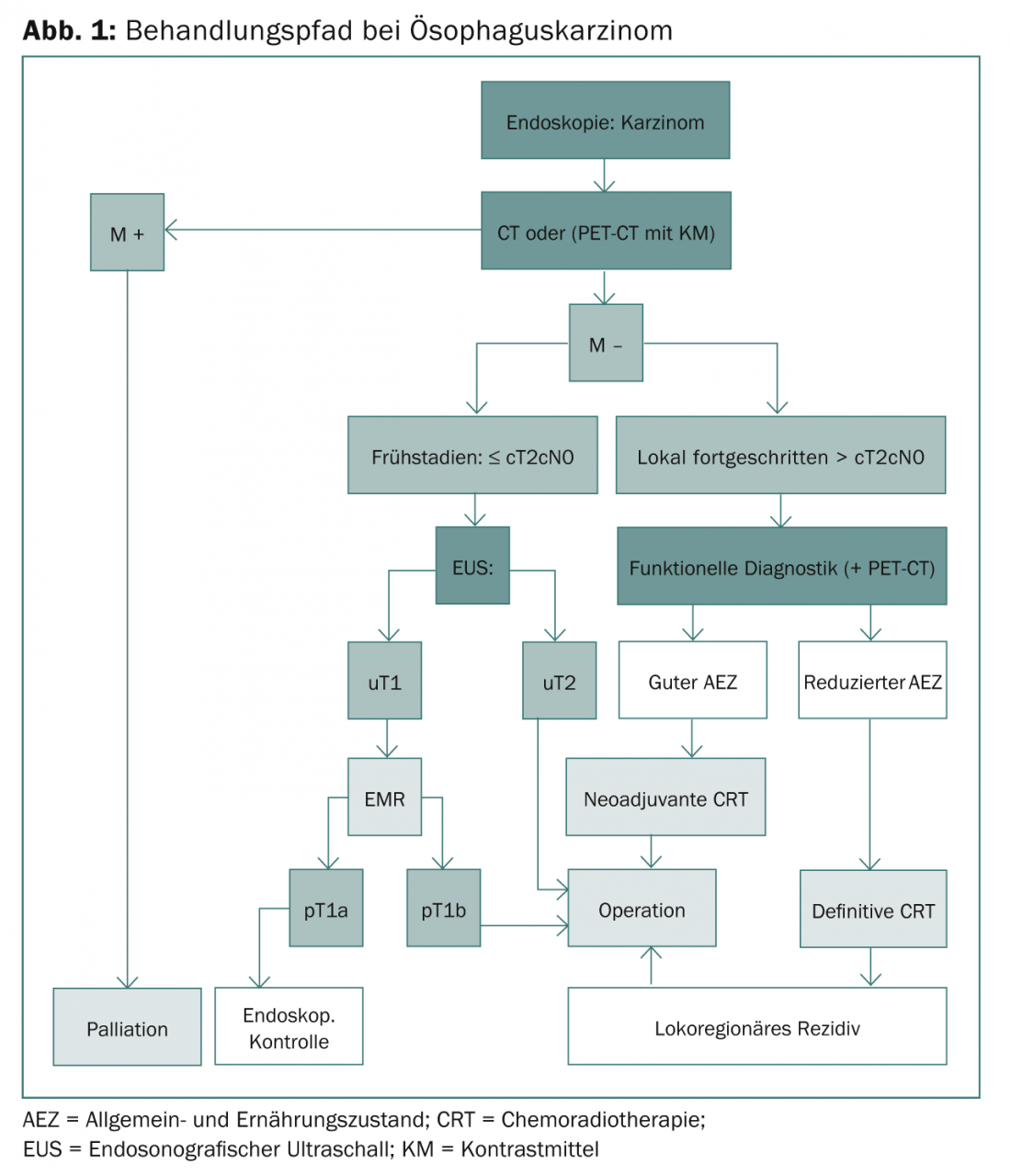

Figure 1 shows the complete treatment pathway for esophageal cancer.

Postoperative course, long-term measures, quality of life

Patients with gastric distention require dietary and lifestyle changes. This means they can only eat small portions, which necessitates snacks between meals and calorie-fortified meals to cover calories. This can improve after years, but there are also some patients who struggle with being able to consume enough calories for life. Quite a few patients suffer from reflux, so that proton blocker intake is necessary in high doses for life. We recommend that all patients raise their headboard in bed and do not lie down after eating. Nevertheless, quite a few patients complain of nocturnal cough, which corresponds to small aspirations.

Frequently, malabsorption with fatty stools, flatulence, and renewed weight loss develops after one year or even later, especially in patients treated trimodally. In most cases, it is an actinic exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, which responds very well to enzyme substitution. In the postoperative course, gastric tube emptying may occur more rapidly, resulting in disruptive hypoglycemia in the sense of dumping. If the treating physician and the patient are sensitized, these symptoms can be avoided very well by dietary means. It usually takes six to twelve months for the patient to recover from an esophagectomy, and very few patients subsequently return to work at 100% in their former profession.

Annelies Schnider, MD

Literature:

- Hölscher AH, et al: Prognostic impact of upper, middle, and lower third mucosal or submucosal infiltration in early esophageal cancer. Ann Surg 2011; 254(5): 802-807.

- Lorenz D, et al: Prognostic risk factors of early esophageal adenocarcinomas. Ann Surg 2014; 259: 469-476.

- Dikken JL, et al: Differences in outcomes of esophageal and gastric cancer surgery across Europe. BJS 2012; 100: 83-94.

- Hulscher JB, et al: Extended transthoracic resection compared with limited transhiatal resection for adenocarcinomas of the esophagus. N Engl J Med 2002; 347: 1662-1669.

- Palmes D, et al: Diagnostic evaluation, surgical techniques, and perioperative management after esophagectomy: consensus statement of the German Advanced Surgical Treatment Group. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2011; 396: 857-866.

- Kim T, et al: Review of Minimally Invasive Esophagectomy and Current Controversies. Gastroenterology Research and Practice 2012.

- Udagawa H, et al: The importance of grouping of lymph node stations and rationale of three-field lymphnodectomy for thoracic esophageal cancer. J Surg Onc 2012; 106: 742-747.

- Nagpal K, et al: Is minimally invasive surgery beneficial in the management of esophageal cancer? A meta-analysis. Surg Endoscop 2010; 24: 1621-1629.

- Luketich JD, et al: Outcomes After Minimally Invasive Esophagectomy. AnnSurg 2012; 256(1): 95-103.

Further reading:

- Hüttl TP, et al: Techniques and results of esophageal cancer surgery in Germany. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2002; 387: 125-129.

- Pennathur A, et al: Resections for esophageal cancer: strategies for optimal management. Ann Thorac Surg 2008; 85: 751-756.

- Briere SS, et al: Minimally invasive versus open esophagectomy for patients with esophageal cancer: a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2012; 379: 1887-1892.

- Marks JL, et al: Salvage esophagectomy after failed definitive chemoradiation for esophageal adenocarcinoma. Ann Thorac Surg 2012; 94: 1126-1132.

- Ruhstaller T, et al: Trends in survival from esophageal cancer in Switzerland. Swiss Cancer Bulletin 2014; 3.

- Hagen P, et al: Preoperative chemoradiotherapy for esophageal or junctional cancer. N Engl J Med 2012; 366: 2074-2084.

- Peyre CG, et al: The number of lymph nodes removed predicts survial in esophageal cancer: An international study on the impact of extent of surgical resections. Ann Surg 2008; 248: 549-556.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2014; 2(10): 18-21.