Early detection of prostate cancer (PCa) was revolutionized with the introduction of PSA (prostate-specific antigen). Since its introduction, however, it has been noticed that a large number of men with low-risk prostate cancer have died with rather than from their carcinoma. In order not to expose these so-called overdiagnoses to additional overtherapy, the possibility of active surveillance was explained in a lecture at the 7th Interdisciplinary Prostate Cancer Symposium in St. Gallen.

In Switzerland, approximately 6200 men per year develop prostate cancer [1]. The number of diagnoses has steadily increased in this country since the introduction of the PSA until 2007 [2]. That this screening reduced the mortality of the disease was demonstrated in 2009 [3]. After an initial more rapid decline in deaths, these have recently been at a fairly constant level [2].

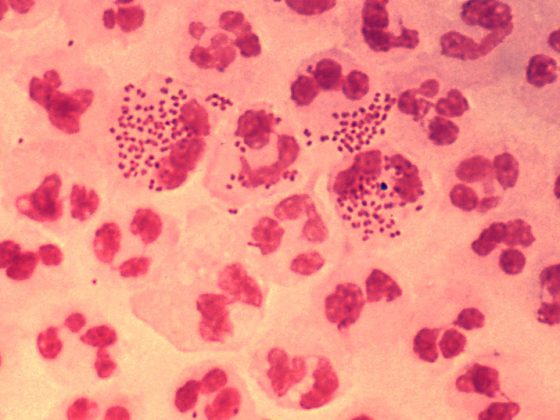

Not all men require therapy immediately upon diagnosis, according to Prof. Axel Semjonow, MD, Head of the Urological Research Laboratory and Center Director of the Prostate Cancer Center of the Department of Urology and Pediatric Urology at Münster University Hospital, Germany. While the PSA as a screening tool succeeds in diagnosing prostate cancer earlier and also reduces mortality, a non-negligible proportion of men are also overdiagnosed by this measure, the speaker said. Overdiagnosis means that the affected person will neither suffer from symptoms of the disease nor die from it in their lifetime. The preconditions for the emergence of overdiagnosis are a large reservoir of asymptomatic patients and the implementation of a screening measure to identify just these. Moreover, there must be forms of this disease that progress so slowly that the patient dies of other causes. That this is true for prostate carcinoma has been demonstrated by autopsy studies of men whose cause of death was not prostate carcinoma [4]. Nearly 60% of men over 80 years of age who died had prostate cancer that was undiagnosed during their lifetime. A systematic review of this evidence led to a European study demonstrating that the diagnosis of PCa is made an average of 11 years earlier in 55-67-year-old men using PSA screening at four-year intervals, with overdiagnosis occurring in approximately 48% [5]. So what can you offer these men now? This is where the possibility of active monitoring comes into play, according to Prof. Semyonov.

Active monitoring

Instead of taking the problem of overdiagnosis into the therapeutic area and thus subsequently also carrying out overtherapy, it is possible to switch to active monitoring under certain conditions. It is important here to highlight the difference between active monitoring and “watchful waiting.” While active surveillance means that curative therapy is delayed under regular monitoring as long as there is no adverse effect, “watchful waiting” describes palliative therapy when symptoms are present.

Inclusion criteria for active surveillance

The studies that address the issue of active surveillance mostly have the following inclusion criteria [6]:

- Very-low-risk carcinomas

- Low-risk carcinomas

- With a life expectancy of <10 years, also intermediate-risk carcinomas

- Barely palpable or non-palpable findings

- Gleason score of max. 6 (exception 3+4 for men with lower life expectancy or advanced age).

- 2-3 infected biopsy cylinders per biopsy run or up to 50%.

- Some studies limit the fraction affected per cylinder to max. 50%

- PSA value of max. 10-20 ng/ml

- PSA density (PSA in relation to prostate volume) <0.2.

The latter marker has so far received quite little attention in the studies performed, but since this seems to be a meaningful marker with regard to prognosis, it will probably be of greater importance in the future, the speaker said.

Controls under active monitoring

If, after detailed consultation with the treating physician, a patient has now decided to initially take the path of active monitoring, control examinations are necessary at regular intervals in order not to miss the time when therapy is necessary. In the various studies on the subject, the following parameters are regularly recorded quite homogeneously:

- the PSA value initially more frequently, then in the course at larger intervals (3/6/12 months)

- the DRU (digital rectal examination) does not play such a big role for the therapy decision (6/12 months)

- Re-biopsies in the first 6-12 months after primary diagnosis, then every 3-4 years.

- Some studies perform mpMRI examinations prior to re-biopsy (to more specifically catch high-grade Gleason scores in the biopsy, mp = multiparametric).

ProPSA and kallikreins are currently being studied to determine if they can make active surveillance safer. Consideration of PSA kinetics alone, i.e., the increase in PSA over a period of time, would lead to a disproportionately high number of men treated too early.

Results of active monitoring

Final results of the studies conducted are not yet available, Prof. Semyonov said. The observation period of 10-15 years was not long enough to assess the mortality of low-risk prostate cancer.

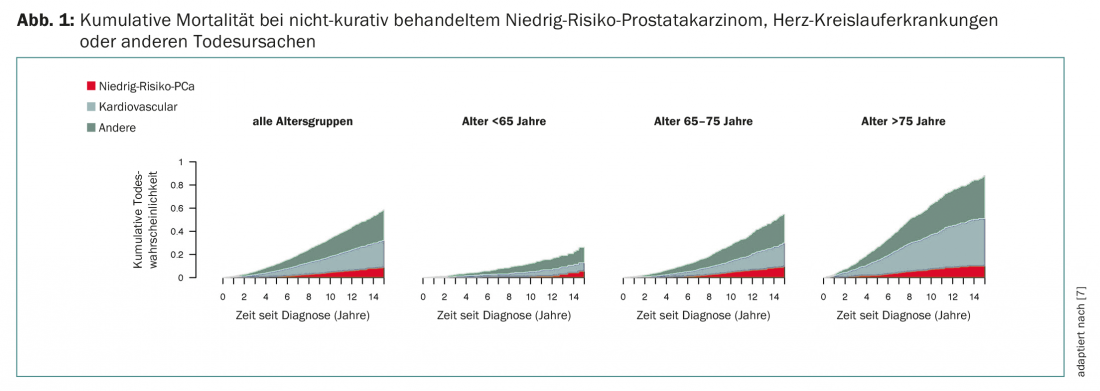

However, study data give cause for optimism. In the study by Rider et al. showed that the proportion of causes of death in men with this same low-risk PCa (Gleason ≤6, PSA <10 ng/ml) changed little after an observation period of 15 years without curative therapy compared with other causes of mortality, independent of age [7]. The vast majority of men died from something other than PCa (Fig. 1). A long-term study in Gothenburg also showed that about 50% of patients with low-risk PCa did not require therapy even after ten years of active surveillance. If therapy was then necessary, there was also a good response to this therapy [8]. In summary, Dr. Laurence Klotz’s work on active surveillance of low-risk PCa. According to his results, this approach is safe in the mentioned patient population with a carcinoma-specific mortality of 1-5% over 15 years [9].

Outlook

To learn even more about the long-term safety and effectiveness of active surveillance, some of the above studies are ongoing. Prof. Semyonov also drew attention to the currently recruiting Prias study (www.prias-project.org), which to date is underway in 22 countries and in over 160 centers. Every treating urologist could include patients here and, after entering the specific data, would also receive recommendations on how to proceed in the respective case.

In Finland, a modified approach to PSA-based screening is currently under investigation [10]. Depending on the baseline PSA level, patients are screened at different intervals. An abnormal PSA value is not immediately followed by biopsy. If the value should be >3 ng/ml, a kallekrein score is determined, if this is positive, an mpMRI follows, if this is suspicious, a biopsy is performed. The goal of this approach is to maintain the mortality reduction of PSA screening while reducing the number of overdiagnoses.

Source: 7th Interdisciplinary Prostate Cancer Symposium, November 9, 2017, St. Gallen.

Literature:

- www.krebsliga.ch/ueber-krebs/krebsarten/prostatakrebs/

- Swiss Federal Statistical Office: Swiss Cancer Report 2015, Status and Development. Prostate Cancer, 83-85. Corrected version from [16 .6.2016].

- Schröder FH, et al: Screening and prostate cancer mortality: results of the European Randomised Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) at 13 years of follow-up. Lancet 2014; 384(9959): 2027-2035.

- Zlotta AR, et al: Prevalence of prostate cancer on autopsy: cross-sectional study on unscreened Caucasian and Asian men. J Natl Cancer Inst 2013; 105(14): 1050-1058.

- Draisma G, et al: Lead times and overdetection due to prostate-specific antigen screening: estimates from the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2003; 95(12): 868-878.

- Tosoian JJ, et al: Active surveillance for prostate cancer: current evidence and contemporary state of practice. Nat Rev Urol 2016; 13(4): 205-215. (Inclusion criteria).

- Rider JR, et al: Long-term outcomes among noncuratively treated men according to prostate cancer risk category in a nationwide, population-based study. Eur Urol. 2013 Jan; 63(1): 88-96.

- Godtman RA, et al: Outcome following active surveillance of men with screen-detected prostate cancer. Results from the Gothenburg randomised population-based prostate cancer screening trial. Eur Urol 2013; 63(1): 101-107.

- Klotz L: Active surveillance and focal therapy for low-intermediate risk prostate cancer. Transl Androl Urol 2015; 4(3): 342-354.

- Auvinen A, et al: A randomized trial of early detection of clinically significant prostate cancer (ProScreen): study design and rationale. Eur J Epidemiol 2017 Jul 31. doi: 10.1007/s10654-017-0292-5. [Epub ahead of print]

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2017; 5(6): 33-35.