Fatigue occurs in almost all oncology patients during the course of the disease. Despite sufficient sleep, sufferers are tired and exhausted – a grueling experience. Since the complaints can still occur years after the therapy, special attention is required here.

Fatigue is a common syndrome that affects approximately 80% of all oncology patients at some point during the course of their disease when systematically searched [1]. This is more than mere fatigue or temporary exhaustion. Those who suffer from fatigue cannot regain their strength and energy through sleep and rest alone. The feeling of tiredness or deep exhaustion bears no relation to previous efforts and lays itself leadenly over all activities of everyday life. Sufferers often suffer from this condition for weeks or even months and report a grueling burden [2,3]. The Swiss Cancer League defines fatigue in its corresponding brochure as a “persistent, difficult-to-overcome, and distressing fatigue that leaves a feeling of total emotional, mental, and physical exhaustion.” [4]

Although fatigue as an accompanying syndrome not only of oncological but also of chronic diseases has received increased attention for about 20 years, the exact mechanisms of its development have not been fully described until today. The therapy is still fraught with many uncertainties. The common assumption that the inflammatory state is the trigger of the fatigue state may be a fallacy according to recent findings [5]. Although chronic inflammation and fatigue often correlate with each other, there was no statistically demonstrable causality between the two variables, at least in the mouse model. Also the occurrence in all stages of different disease patterns and in consequence of different therapies suggests a multifactorial process. Various publications have postulated diverse risk factors not directly related to cancer, such as low socioeconomic status, higher BMI, psychological or physical comorbidities for the development of the syndrome [6 – 8]. Nevertheless, many patients without these predisposing factors also suffer from fatigue [9]. It is certain that both the cancer itself and its therapy can contribute to its development [3]. For example, 80-96% of patients undergoing chemotherapy and 60-93% of patients undergoing radiotherapy are affected, many for several years after treatment is completed [9 –12]. A chronification of the extreme state of exhaustion occurs in 20-50% of the affected patients, without it being possible to predict which patient group is particularly at risk in this respect [3].

Diagnostics

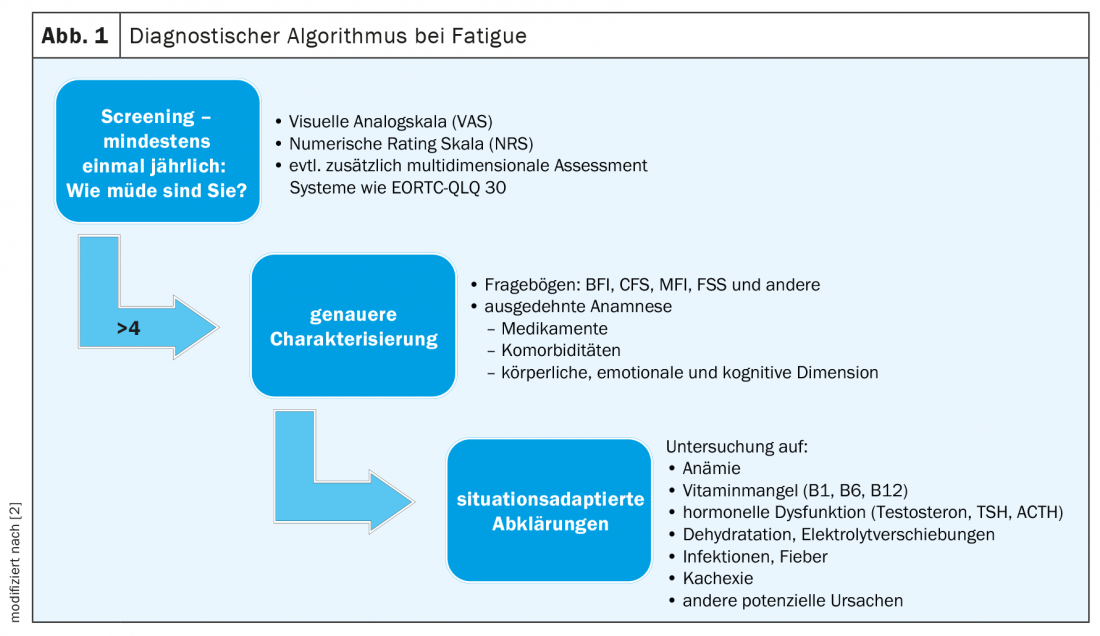

Unfortunately, even today, many patients suffering from fatigue are deprived of adequate therapy due to a lack of awareness of their symptoms [1]. It is a silent syndrome that rarely occurs in isolation. Furthermore, the presence of severe fatigue is too often considered normal by patients, as well as by physicians and nurses, given the disease and the intensive therapy. A first decisive step towards improved recognition and thus treatment of fatigue therefore already consists in the consistent implementation of a screening. One is recommended by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) from the time of tumor diagnosis and at least annually thereafter, even after completion of treatment [13]. A simple assessment of severity on a visual (VAS) or numeric (NRS) scale of 0 -10 is suggested as an initial tool, with scores between 1 and 3 indicating mild fatigue, scores between 4 and 6 indicating moderate fatigue, and scores above 6 indicating severe fatigue. Simple, open-ended questions such as “How tired do you feel?” or “How much does fatigue bother you?” should be used for screening [1]. Patients who complain of a moderate or severe manifestation should be referred for more differentiated clarification. (Fig 1).

In addition, to facilitate the assessment of distress and evaluate potential co-factors, a multidimensional assessment can be performed, for example, with the Core Quality of Life Questionnaire of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC QLQ-C30) [1,14]. This tool contains 30 questions and assesses the quality of life of oncology patients across 10 subscales. It allows a classification of the subjective evaluation of fatigue in relation to that of other symptoms. For certain cancers, the questionnaire was further developed and adapted more precisely to the respective condition. For example, there is QLQ BR23 for patients with breast cancer. Numerous other uni- and multidimensional instruments exist to quantify and better classify fatigue, but unfortunately often only their English versions are scientifically validated [15]. These include, for example, the Brief Fatigue Inventory (BFI), the Chalder Fatigue Scale (CFS), the Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS), and the Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI). The German version of the FSS has also been validated in a large Swiss cohort with different, albeit non-oncological, clinical pictures and allows an assessment of severity through nine questions [16]. An overview of existing fatigue characterization tools is provided in the systematic review by Minton et al. [15].

Even if self-assessment is not possible, screening should not be completely abandoned [1]. A third-party history with relatives on activity levels, sleepiness, and bedtimes can provide good clues.

After more detailed characterization of the complaints, possible treatable causes must be excluded. There is no generally applicable algorithm for this purpose; rather, further investigations should be based on the specific situation [1]. Prognosis, previous and planned oncological therapies, the patient’s life plan and treatment goals play a role, as do known comorbidities and other described risk factors. In principle, before taking further diagnostic and therapeutic steps, the practitioner should clarify whether the patient is in a clearly curative situation or whether palliation already occupies a large space. In far advanced stages of the disease, detailed diagnostics and especially pharmacological attempts to remedy fatigue may no longer be indicated or may even be counterproductive [2,17]. Some common concomitants of oncological diseases such as depression, sleep disorders, malnutrition and anemia often lead to fatigue and exhaustion and can be both differentiated clarified and treated. Furthermore, adverse drug reactions are common co-triggers of fatigue.

Therapy

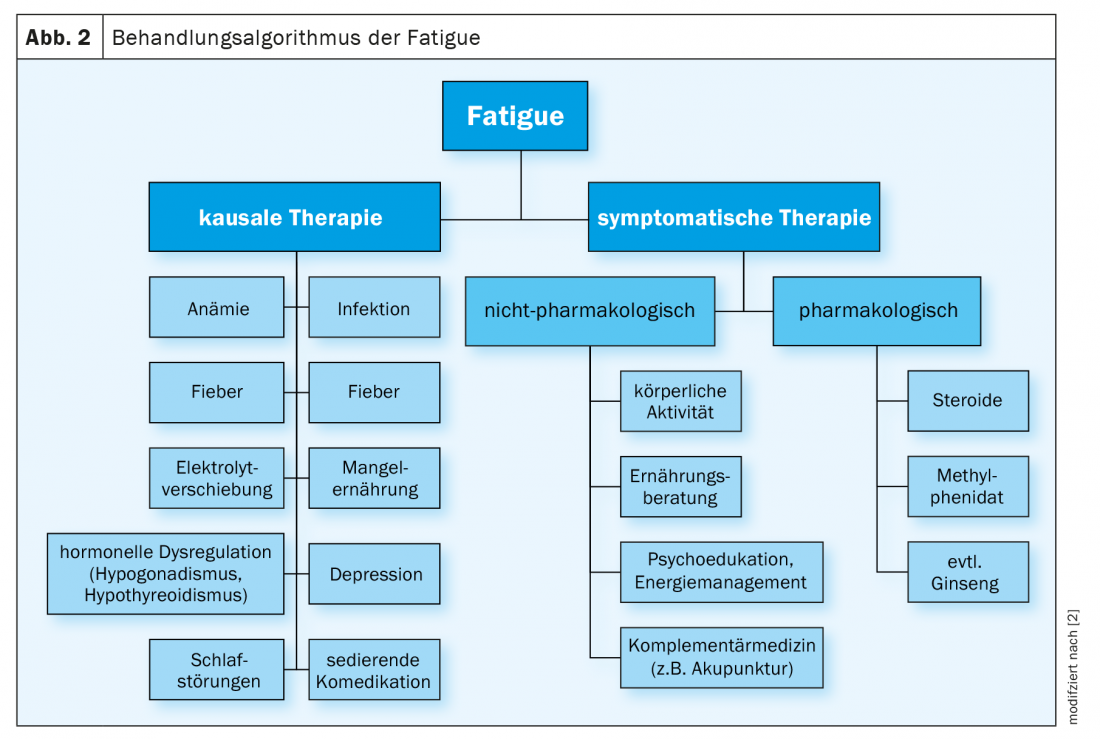

Symptomatic treatment of fatigue is based on the three pillars of information, nonpharmacological measures, and pharmacological interventions. In accordance with the multi-causal genesis, a multidimensional approach must also be taken in therapy as a rule. Correction of only one potentially causal factor is unlikely to lead to relevant improvement, especially in patients in a palliative situation [17]. Nevertheless, the treatment of conditions known to cause severe fatigue, such as anemia, hypothyroidism, dehydration, or acute inflammatory state, is paramount (Fig. 2) [1,2]. The ongoing evaluation of the measures taken is important. For example, if oxygen administration is initiated based on the hypothesis that hypoxemia causes fatigue and there is no improvement in symptoms, therapy should not be continued uncritically [17]. The subjective experience of the patients is decisive for the control of success with regard to the effectiveness of the therapeutic measures taken [1]. Regular recording of the severity of fatigue via the instruments also used at the start of therapy helps to document the course and to make treatment decisions more comprehensible.

Information and counseling: The information of patients and relatives about fatigue takes a high priority and is at the beginning of every successful treatment [1]. Potential causal factors and possible courses are to be addressed as well as manifestations and coping strategies. It is important to encourage those affected to adopt a conscious approach to their own strengths and to learn about their resources. Thus, moments with a lot of energy should be used effectively [1]. It is worth emphasizing that fatigue may be a consequence of – otherwise successful – oncologic treatment and is not necessarily due to disease progression [13]. Existing patient information can be used to facilitate education, such as the brochure of the Swiss Cancer League or the corresponding publication of the German Cancer Aid [4,18]. These can help sufferers and practitioners find a common language. They also include questionnaires that can be used for re-evaluation during the course. Jointly setting realistic treatment goals prevents disappointment and treatment discontinuation and reduces the pressure on those affected [1,17]. Patients usually need space for their emotions; in order to understand and accept fatigue as a syndrome, time and understanding on the part of the practitioner is necessary in addition to sufficient information [1].

It is important for counseling to know that fatigue in oncology patients can be significantly improved by energy conservation and activity management [20]. Appropriate strategies include conserving energy through delegation and prioritization, as well as an adequate amount of rest and activity periods in a set daily structure with regular sleep patterns [13]. In order to successfully implement these approaches, it is essential to involve and educate the surrounding community. Social counseling can be helpful for network coordination as well as financial and employment issues. Depending on the situation, relief services may also be called upon.

Non-drug treatment: exercise and nutritional therapy approaches, psychosocial interventions, and complementary medicine methods are part of the multidimensional treatment strategy [1,2]. The most evidence exists for the effectiveness of aerobic physical training [2,21–23]. Thus, structured exercise sessions have been shown to improve fatigue. Implementing them, however, is anything but easy, since the downward spiral of increasing exhaustion, which reinforces resistance to activation, must first be broken. Most patients understandably react to their fatigue with increased rest periods and a reduced need for exercise, which in the course of time further intensifies the complaints and does not improve them [24]. Ideally, several training sessions of at least 30 minutes each should be completed per week, especially in the form of endurance training. A combination with muscle building exercises seems to be useful and there is evidence that supervision by qualified professionals such as sports therapists is beneficial [3,23]. The activation program should be adapted to the capacity and needs of the person concerned. Thus, depending on the stage of disease, even the smallest activities, such as sitting at mealtimes, are of clinical benefit [1,3]. Exercise in a group setting can have additional psychosocial benefits and increase motivation. To prevent the vicious cycle of deconditioning and fatigue, physical activity should be recommended to all oncology patients at the time of diagnosis.

Regarding the role of nutrition in the treatment of fatigue, less clear recommendations exist. If malnutrition is also a potential cause, it is more likely to have an impact on physical strength [1]. Nevertheless, nutrition counseling may also be useful for educating and informing family members. Often, the importance of diet is overstated in the context of fighting tumor cells, which can put tremendous pressure on those affected [1]. A structured approach allows unrealistic expectations to be countered with information and concrete measures. As far as possible, individual preferences should be taken into account. For the treatment of fatigue, in addition to the prevention of deficiency symptoms, particular attention should be paid to a balanced electrolyte balance and adequate fluid intake [13].

Despite the intensified research efforts in this area in recent years, there is currently no broad data base on psychosocial interventions for fatigue. Certain approaches, however, seem to be having an effect. These include cognitive behavioral therapy, psychoeducation, cognitive restructuring, mindfulness-based meditation, and systematic learning of coping strategies [25 –28]. Group therapy and support groups can also be of great benefit to sufferers [1,29].

Complementary treatment approaches include therapeutic massage, acupuncture, yoga, light therapy, and other mind-body procedures [30 –35]. A recent meta-analysis compared the efficacy of different nonpharmacologic interventions for fatigue [32]. In the overall analysis of individual measures, cognitive behavioral therapy and qigong had the best effects. However, the superiority of individual methods depended in each case on the screening instrument chosen (see above). A universal recommendation on the best choice of nondrug interventions cannot be made on the basis of a meta-analysis. Certainly, the preferences and the initial situations of the persons concerned have a decisive influence on the possible success.

Drug treatment: Methylphenidate (Ritalin®) and modafinil (Modasomil®) have been used for a long time for the pharmacological treatment of fatigue, both in off-label use and with inconclusive evidence [2]. In addition, there are positive data for the use of steroids and ginseng [1]. In contrast, the efficacy of other stimulant drugs such as donepezil is highly controversial, and routine use of amantadine, paroxetine, Remeron, megestrol, and L-carnitine is discouraged [1,2]. As in the specific treatment of triggering factors, the principle also applies here that medication must be stopped again sufficiently early if the therapeutic goals are not achieved [1]. Furthermore, it should be noted that in patients with fatigue, significant improvement in symptoms has also been demonstrated in RCTs in the respective placebo group [36]. This puts into perspective the importance of study results that attribute effects to specific substances and illustrates why there is no clear evidence for an active ingredient to date.

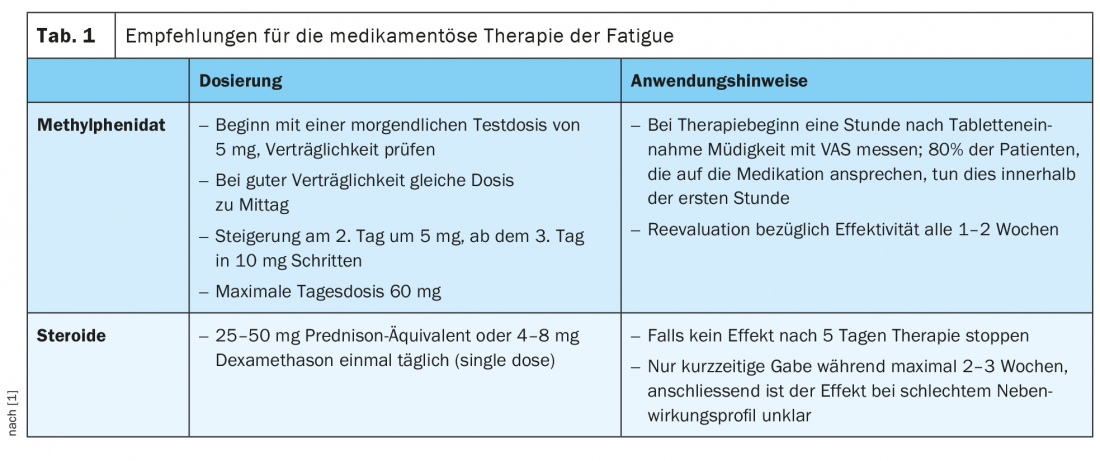

Methylphenidate is one of the substances that have been tested in several studies as effective in the treatment of fatigue [37– 40]. However, there are also data questioning the beneficial effect of this agent [41,42]. For the treatment of fatigue, it is recommended to start with a morning test dose of 5 mg and, if well tolerated, to administer the same dose at noon. Subsequently, an increase to a maximum daily dose of 60 mg can be made, but this is rarely necessary (Tab. 1) [1]. Because most patients who respond to methylphenidate do so within the first hour, fatigue should be assessed by VAS one hour after administration of the first adequate dose. Modafinil could also potentially alleviate symptoms associated with fatigue, but fewer studies exist on this with equally conflicting results [40,43,44]. The use of modafinil is accordingly discouraged, for example in the Bigorio consensus paper of the Swiss Palliative Care Expert Group [1].

Corticosteroids, on the other hand, are widely used for temporary relief of fatigue, especially in the advanced stages of the disease, and indeed some studies show positive effects on symptoms [45 – 47]. Nevertheless, the data situation here also remains without clear evidence, especially with regard to a longer-term benefit. In addition, because corticosteroids have an unfavorable side effect profile, they should be used only selectively and for no longer than two to three weeks for the indication of fatigue [1]. Administration of 25 – 50 mg prednisone equivalent or 4 – 8 mg dexamethasone once daily, preferably in the morning, is recommended. (Tab 1). If no effect can be demonstrated after five days, therapy should be stopped [1].

Ginseng is a lesser known pharmacological approach in fatigue control. Some studies have demonstrated benefits from both American and Asian ginseng [48 –50]. However, further methodologically sound studies are needed to make definitive recommendations [50]. The favorable risk profile is certainly an advantage of this agent.

The palliative situation

In advanced, palliative and especially concrete end-of-life disease stages, relevant alleviation of fatigue may no longer be a treatment goal. There are authors who consider pronounced fatigue as a protective function to reduce suffering at the end of life [2,17]. Often, in this situation, the suffering pressure of those affected by exhaustion decreases, since inner and outer demands regarding functioning in everyday life no longer exist or hardly exist, a long path of psychological and mental adjustment and, if necessary, acceptance lies behind them. Nevertheless, the right time for an appropriate strategy adjustment in fatigue treatment is not always easy and can only be identified with the help of the patients. It should not be missed [17].

If treatment of fatigue is desired and appropriate, the same therapeutic principles apply as for patients in the active oncologic therapy phase or remission. Overall, however, the data for those in terminal stages of disease are less robust. Again, educating patients and family members about the syndrome plays an important role. There are also some studies showing that adapted physical activity programs can have benefits even in the palliative setting [51,52]. Other non-pharmacological methods such as psychosocial interventions that can help instill a sense of dignity have also been shown to be effective [53,54]. The use of complementary and medicinal therapies should be adapted to needs and continuously re-evaluated.

Take-Home Messages

- Fatigue is a common syndrome among oncology patients with serious impact on quality of life that is often not adequately treated. The symptoms may persist even years after cancer therapy has been completed.

- It is a multidimensional syndrome with physical, emotional and cognitive components. All components must be considered in diagnostics and therapy.

- Screening is recommended at the time of cancer diagnosis and at least annually thereafter using Visual Analog Scale (VAS) or Numeric Rating Scale (NRS), beyond the completion of treatment. If values >4, further diagnostics should be performed.

- Adequate therapy consists of information, nonpharmacologic interventions, and pharmacologic interventions when appropriate. In particular, psychoeducation and regular physical activity play an important role. Limited medication options include methylphenidate, steroids, and ginseng.

- Fatigue has a certain protective function in terminal stages of the disease. A forced, especially pharmacological therapy is not indicated in this situation and may even be counterproductive.

Literature:

- Ducret S, et al: Bigorio 2013 – “Fatigue”. Consensus on “best practice” for palliative care in Switzerland – palliative ch expert group. www.palliative.ch/2013

- Radbruch L, et al: Fatigue in palliative care patients — an EAPC approach. Palliat Med 2008; 22(1): 13-32.

- von Kieseritzky K: Fatigue in cancer. www.krebsgesellschaft.de/2018. Updated 05.07.2018. Available from: www.krebsgesellschaft.de/onko-internetportal/basis-informationen-krebs/basis-informationen-krebs-allgemeine-informationen/fatigue-bei-krebs.html.

- Bachmann-Mettler I, Lanz S, Lienhard A: Tired all around: fatigue in cancer. Information brochure of the Swiss Cancer League 2014.

- Grossberg AJ, et al: Tumor-Associated Fatigue in Cancer Patients Develops Independently of IL1 Signaling. Cancer Res 2018; 78(3): 695-705.

- Bower JE, et al: Fatigue in breast cancer survivors: occurrence, correlates, and impact on quality of life. J Clin Oncol 2000; 18(4): 743-753.

- Donovan KA, et al: Utility of a cognitive-behavioral model to predict fatigue following breast cancer treatment. Health Psychol 2007; 26(4): 464-472.

- Mitchell SA: Cancer-related fatigue: state of the science. PM R 2010; 2(5): 364-383.

- Bower JE: Cancer-related fatigue mechanisms, risk factors, and treatments. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2014; 11(10): 597-609.

- Stasi R, et al: Cancer-related fatigue: evolving concepts in evaluation and treatment. Cancer 2003; 98(9): 1786-1801.

- Reinertsen KV, et al: Fatigue During and After Breast Cancer Therapy-A Prospective Study. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017; 53(3): 551-560.

- Ebede CC, Jang Y, Escalante CP: Cancer-Related Fatigue in Cancer Survivorship. Med Clin North Am 2017; 101(6): 1085-1097.

- Bower JE, et al: Screening, assessment, and management of fatigue in adult survivors of cancer: an American Society of Clinical oncology clinical practice guideline adaptation. J Clin Oncol 2014; 32(17): 1840-1850.

- Aaronson NK, et al: The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 1993; 85(5): 365-376.

- Minton O, Stone P: A systematic review of the scales used for the measurement of cancer-related fatigue (CRF). Ann Oncol 2009; 20(1): 17-25.

- Valko PO, et al: Validation of the fatigue severity scale in a Swiss cohort. Sleep 2008; 31(11): 1601-1607.

- Neuenschwander H: Handbook of palliative care. 3rd edition, Verlag Hans Huber 2015.

- Beckmann I-A: Fatigue: chronic fatigue in cancer. Information brochure of the German Cancer Aid Foundation.

- Information sheet of the Swiss Cancer League: Dealing with fatigue during or after cancer. www.krebsliga.ch.

- Barsevick AM, et al: A randomized clinical trial of energy conservation for patients with cancer-related fatigue. Cancer 2004; 100(6): 1302-1310.

- Mock V: Evidence-based treatment for cancer-related fatigue. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2004; 2004(32): 112-118.

- Speck RM, et al: An update of controlled physical activity trials in cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cancer Surviv 2010; 4(2): 87-100.

- Brown JC, et al: Efficacy of exercise interventions in modulating cancer-related fatigue among adult cancer survivors: a meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2011; 20(1): 123-133.

- Richardson A, Ream EK: Self-care behaviors initiated by chemotherapy patients in response to fatigue. Int J Nurs Stud 1997; 34(1): 35-43.

- Lengacher CA, et al: Examination of Broad Symptom Improvement Resulting From Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction in Breast Cancer Survivors: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34(24): 2827-2834.

- Duijts SF, et al: Effectiveness of behavioral techniques and physical exercise on psychosocial functioning and health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients and survivors–a meta-analysis. Psychooncology 2011; 20(2): 115-126.

- Sandler CX, et al: Randomized Evaluation of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy and Graded Exercise Therapy for Post-Cancer Fatigue. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017; 54(1): 74-84.

- Gok Metin Z, et al: Effects of progressive muscle relaxation and mindfulness meditation on fatigue, coping styles, and quality of life in early breast cancer patients: An assessor blinded, three-arm, randomized controlled trial. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2019; 42: 116-125.

- Spiegel D, Bloom JR, Yalom I.: Group support for patients with metastatic cancer. A randomized outcome study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1981; 38(5): 527-533.

- Khanghah AG, et al: Effects of Acupressure on Fatigue in Patients with Cancer Who Underwent Chemotherapy. J Acupunct Meridian Stud 2019; 12(4): 103-110.

- Miller KR, et al: Acupuncture for Cancer Pain and Symptom Management in a Palliative Medicine Clinic. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2019; 36(4): 326-332.

- Wu C, et al: Nonpharmacological Interventions for Cancer-Related Fatigue: A Systematic Review and Bayesian Network Meta-Analysis. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs 2019; 16(2): 102-10.

- Dikmen HA, Terzioglu F: Effects of Reflexology and Progressive Muscle Relaxation on Pain, Fatigue, and Quality of Life during Chemotherapy in Gynecologic Cancer Patients. Pain Manag Nurs 2019; 20(1): 47-53.

- Pan YQ, et al: Massage interventions and treatment-related side effects of breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Clin Oncol 2014; 19(5): 829-841.

- Redd WH, et al: Systematic light exposure in the treatment of cancer-related fatigue: a preliminary study. Psychooncology 2014; 23(12): 1431-1434.

- de la Cruz M, et al: Placebo and nocebo effects in randomized double-blind clinical trials of agents for the therapy for fatigue in patients with advanced cancer. Cancer 2010; 116(3): 766-774.

- Pedersen L, et al: Methylphenidate as Needed for Fatigue in Patients With Advanced Cancer. A Prospective, Double-Blind, and Placebo-Controlled Study. J Pain Symptom Manage 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.05.023. epub ahead of print.

- Sugawara Y, et al: Efficacy of methylphenidate for fatigue in advanced cancer patients: a preliminary study. Palliat Med 2002; 16(3): 261-263.

- Sarhill N, et al: Methylphenidate for fatigue in advanced cancer: a prospective open-label pilot study. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2001; 18(3): 187-192.

- Qu D, et al: Psychotropic drugs for the management of cancer-related fatigue: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2016; 25(6): 970-979.

- Bruera E, et al: Patient-controlled methylphenidate for cancer fatigue: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2006; 24(13): 2073-2078.

- Moraska AR, et al: Phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of long-acting methylphenidate for cancer-related fatigue: North Central Cancer Treatment Group NCCTG-N05C7 trial. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28(23): 3673-3679.

- Tomlinson D, et al: Pharmacologic interventions for fatigue in cancer and transplantation: a meta-analysis. Curr Oncol 2018; 25(2): e152-e67.

- Spathis A, et al: Modafinil for the treatment of fatigue in lung cancer: results of a placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized trial. J Clin Oncol 2014; 32(18): 1882-1888.

- Begley S, Rose K, O’Connor M: The use of corticosteroids in reducing cancer-related fatigue: assessing the evidence for clinical practice. Int J Palliat Nurs 2016; 22(1): 5-9.

- Bruera E, et al: Action of oral methylprednisolone in terminal cancer patients: a prospective randomized double-blind study. Cancer Treat Rep 1985; 69(7-8): 751-754.

- Paulsen O, et al: Efficacy of methylprednisolone on pain, fatigue, and appetite loss in patients with advanced cancer using opioids: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. J Clin Oncol 2014; 32(29): 3221-3228.

- Arring NM, et al: Integrative Therapies for Cancer-Related Fatigue. Cancer J 2019; 25(5): 349-356.

- Barton DL, et al: Wisconsin ginseng (Panax quinquefolius) to improve cancer-related fatigue: a randomized, double-blind trial, N07C2. J Natl Cancer Inst 2013; 105(16): 1230-1238.

- Arring NM, et al: Ginseng as a Treatment for Fatigue: A Systematic Review. J Altern Complement Med 2018; 24(7): 624-633.

- Chen YJ, et al: Exercise Training for Improving Patient-Reported Outcomes in Patients With Advanced-Stage Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Pain Symptom Manage 2020; 59(3): 734-749.

- Dittus KL, Gramling RE, Ades PA: Exercise interventions for individuals with advanced cancer: A systematic review. Prev Med 2017; 104: 124-132.

- Kissane DW, et al: Meaning and Purpose (MaP) therapy II: Feasibility and acceptability from a pilot study in advanced cancer. Palliat Support Care 2019; 17(1): 21-28.

- Breitbart W, et al: Pilot randomized controlled trial of individual meaning-centered psychotherapy for patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30(12): 1304-1309.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2020; 8(5): 6-11.