In spite of widespread and everyday use in practice, there are often inconsistent procedures and ambiguities in material selection, change interval and complication management in urinary tract catheter drainage. Advances in the field of antisepsis and improvements in catheter material and technique have made urinary tract drainage a safe procedure with few complications over the past decades. The following article provides an overview of the various forms of urinary catheters in practical-clinical and hygienic-infectiological terms.

Transurethral indwelling bladder catheters

For the insertion of a transurethral indwelling bladder catheter, a physician’s indication is mandatory; after insertion, this indication must be checked daily and the catheter must be removed at the earliest possible time [1]. The insertion itself can be performed by trained caregivers if the correct technique and appropriate catheter material are known, sufficient practical practice is available, and the necessary knowledge of aseptics and antiseptics is available. The insertion procedure is strictly aseptic; the required sterile materials are taken from standardized catheterization sets. When selecting anesthetic lubricants, pay attention to allergies (lidocaine) and when selecting the antiseptic, pay attention to mucosal compatibility and contact time (e.g. Octenisept® 1 min). Hygienic hand disinfection is required before and after manipulation of a bladder catheter including the drainage system. To limit intraluminal ascending infections, use only sterile closed urinary drainage systems with draining devices. A drip chamber and flap valve prevent urine from flowing back from the collection bag into the catheter. Catheter and drainage tubing must not be kinked, the urine collection bag must always be secured below the level of the bladder, and disconnection of the drainage system must be minimized. In case of disconnection, the reconnection of the catheter cone and drainage tube may only be performed aseptically after prior spray and wipe disinfection with an alcohol-based preparation. For daily catheter care, the extracorporeal catheter portion and the external genitals should be cleaned with soap and water [2].

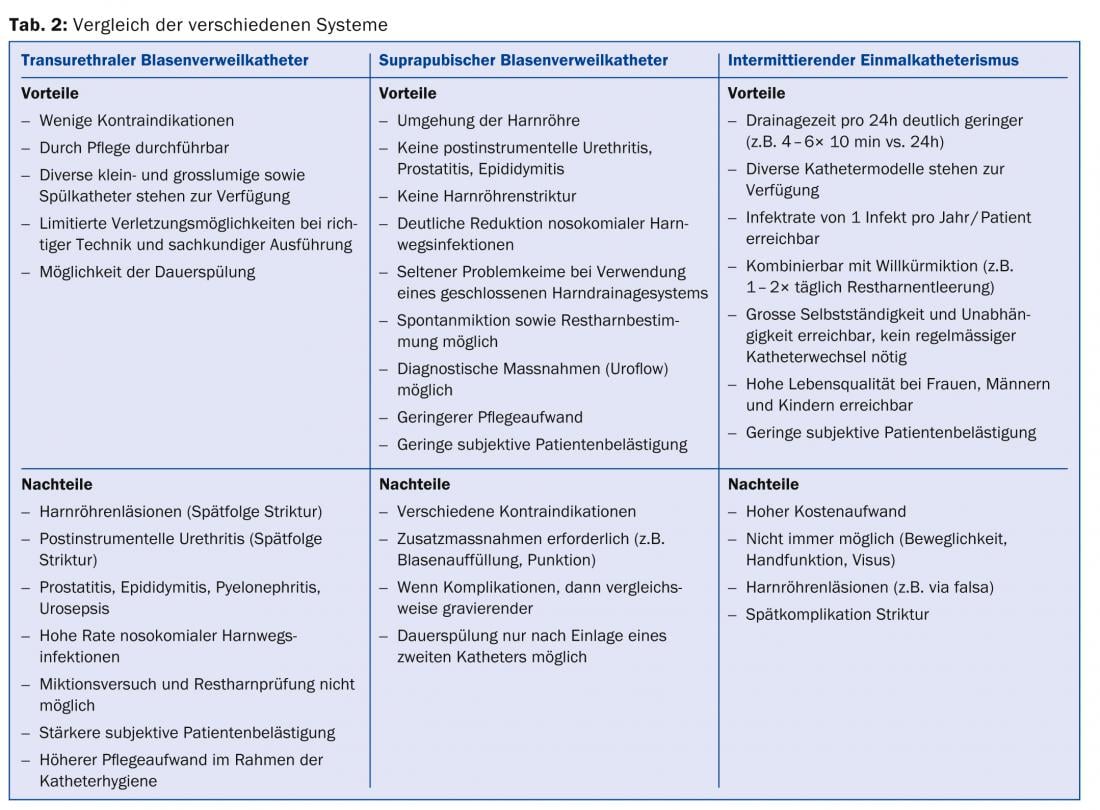

The transurethral indwelling bladder catheter, the most common type of catheter, is frequently associated with complications, particularly urinary tract infections. The risk of infection increases with recumbency and is greater in women than in men. Nine out of ten nosocomial urinary tract infections are catheter-associated. The daily incidence of newly acquired bacteriuria ranges from 3% to 10% in transurethrally catheterized patients, so that bacteriuria can be detected in virtually all patients after 30 days [3]. Germ ascension occurs intraluminally after disconnection and extraluminally due to a biofilm between the catheter surface and the urethral mucosa. Approximately one quarter of all urethral strictures in male patients are due to a transurethral indwelling bladder catheter as the cause [4]. Patients with chronic transurethral catheterization for six years may develop squamous cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Tumor-related mortality in these patients is 0.3-2.8% [5]. Therefore, avoiding long-term catheter drainage of the urinary tract is an essential goal in the care of patients with voiding dysfunction.

Suprapubic indwelling bladder catheters

The indication and placement of the suprapubic catheter are medical activities. If the patient stays five days or more, the bladder should be drained suprapubically. The insertion is usually performed under local anesthesia, taking into account the contraindications. With proper indication and technique, complications are rare (macrohematuria with need for bladder irrigation in 2-4%, catheter dislocation in 0.7-8.0%, malpuncture in <3%, urine leakage next to the catheter in <1%, and perivesical hematoma or urinoma in <0.1%) [6]. The suprapubic approach avoids traumatic and inflammatory complications of the urethra, prostate, and epididymis. In contrast to the transurethral catheter, the suprapubic catheter allows bladder training with voluntary micturition via the urethra and residual urine determination via the catheter. Urinary tract infections and problem germs occur later and less frequently with the suprapubic compared to the transurethral catheter. The wearing comfort is good, especially when using silicone catheters. The puncture site and also the catheter should be cleaned daily with soap and water; a few weeks after placement, a dressing is often no longer necessary.

Catheter material, balloon block, change interval and valve supply

Inexpensive indwelling catheters made of uncoated latex are still regularly used. Their rough and porous material surface favors incrustations and urethral irritations, which is why they should only be used if a latex allergy is excluded and a short retention time of less than five days is intended. Silicone, on the other hand, is soft and elastic and has a relatively smooth surface compared to other materials. For long-term urinary drainage (five days and longer), only solid silicone catheters should be used. The risk of traumatic or inflammatory urethral complications increases with the outer diameter of the catheter. As a rule, the catheter thickness should not exceed 18 Charriere. For short-term transurethral urinary drainage, the use of a 12-Charr catheter ensures adequate drainage performance [7, 12].

The balloon is blocked with a sterile eight to ten percent glycerine solution, which prevents spontaneous unblocking even if the balloon is left in place for a long time. Physiological saline solutions as well as other crystalloid solutions (X-ray contrast media or glucose solutions) can incrust and agglutinate the block channel and hinder subsequent unblocking of the catheter. Balloon filling with more than 10 ml can lead to bladder desesmia. Reduction of filling alone may improve these symptoms, and supplemental anticholinergic bladder dampening is helpful. Excessive balloon volume may impede complete emptying of the urinary bladder because the drainage orifice at the catheter tip is lifted by the balloon. The “residual urine” resulting in this way despite continuous drainage can promote the development of urinary tract infections and, in conjunction with bladder tenesmus, also explains the involuntary leakage of urine next to the catheter. In patients who do not present a concern for accidental catheter removal due to agitation or dementia, balloon inflation of 5-10 ml is sufficient [7, 12].

The indwelling duration of a bladder indwelling catheter depends on the material properties of the catheter and factors such as diuresis, infection and the resulting tendency to incrustation and contamination. Catheters should no longer be routinely changed at fixed intervals, but rather as needed based on individual considerations, as the length of change intervals is subject to patient-dependent variations. A catheter does not need to be changed as long as free urine flow and clear urine are ensured, no local or systemic signs of infection are present and the patient is symptom-free. For any type of catheter drainage, its earliest possible removal serves to prevent complications. Therefore, with each catheter change, the indication for continued catheter drainage of the urinary bladder should be reassessed [7, 12].

If the ability of the urinary bladder to store a certain amount of urine is preserved, a catheter valve can be used in place of open drainage into a urine bag. If the bladder sensor is intact after urge or otherwise after a fixed time interval, the urine is emptied by opening the valve. Filling quantities of significantly more than 500 ml should be avoided. According to manual abilities and preferences, it is possible to choose from a range of different models, such as products that can be operated with one hand and with both hands. Each time the catheter is changed, the valve is also changed.

Intermittent disposable catheterization

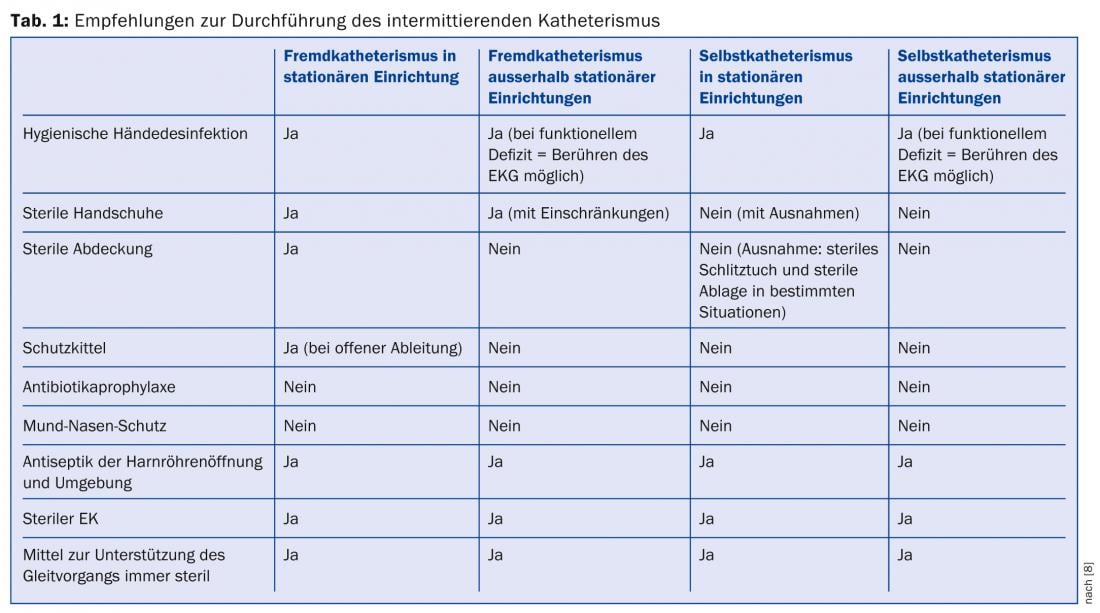

For chronic voiding dysfunction, avoiding an indwelling bladder catheter is a primary goal. Originally developed for paraplegic patients, intermittent disposable catheterization is now considered the gold standard for neurogenic bladder dysfunction with urinary retention and non-neurogenic, non-obstructive urinary bladder voiding dysfunction. Catheterization of the urinary tract must always be performed aseptically; this also applies to intermittent catheterization. The technique is largely standardized, and working instructions exist in the form of a recommendation by a panel of experts (Tab. 1) [8].

Important prerequisites on the patient side for the successful establishment of intermittent disposable catheterization are motivation as well as sufficient physical mobility, hand function and vision. Expert instruction, including training and, if necessary, correction of the technique, as well as advice on suitable catheter models, is usually provided by specially trained nurses at neurourological centers. Once the learning curve has been completed and provided that appropriate care is taken during the procedure, a course with few complications and infections is possible over many years and a very good quality of life can be achieved.

Various sterile-packaged catheter systems are available for intermittent disposable catheterization. A distinction is made between hydrophilic, pre-coated catheters and those used together with a lubricant to be applied separately. New catheters introduced in recent years include short catheters developed specifically for women (e.g., LoFric Sense), a movable, atraumatic catheter tip (e.g., Sauer IQ Cath, Fig. 1) , or completely non-contact handling with insertion aid and protective sheath (Hollister VaPro, Fig. 2) .

Literature data on stricture rates during single-use catheterization vary from just under 3% [9] to 21% [10]. If the aseptic catheterization technique is used, a rate of no more than one infection/patient/year can be achieved without infection prophylaxis [11]. Compared to transurethral and suprapubic bladder catheters, intermittent catheterization is by far the least complicated alternative to catheter drainage of the bladder in cases of bladder dysfunction (Table 2).

PD André Reitz, MD

Literature:

- 1 Wong ES, Hooton TM: Guidelines for prevention of catheter-associated urinary tract infections. Infect Control 1981; 2: 126-130.

- 2. Kunin CM: Prevention in catheter-associated infections. In: Kunin CM: Urinary tract infections. Detection, prevention,and management. Williams &Wilkins, Baltimore 1996; 245-278.

- Bruühl P, Kramer A, Klebingat KJ: Catheter-mediated nosocomial urinary tract infection. In: Bach D, Brühl P (eds.): Nosocomial urinary tract infections. Jungjohann, Neckarsulm 1995; 1-5.

- Hofstetter A: Urogenital infections. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg New York Tokyo 1999.

- Pannek J: Transitional cell carcinoma in patients with spinal cord injury: a high risk malignancy? Urology 2002; 59: 240-244.

- Meessen S, Brühl P, Piechota HJ: A new suprapubic cystostomy trocar system. Urology 2000; 56: 315-316.

- Piechota HJ, et al: Catheter drainage of the urinary bladder today. Dtsch Ärzteblatt 2000; A 7: 168-174.

- Stöhrer M, Sauerwein D: Intermittent catheterization in neurogenic bladder dysfunction. Urologist 2001; B 41: 362-368.

- Günther M, et al: Effects of aseptic intermittent catheterization on the male urethra. Urologist 2001; B 41: 359-361.

- Wyndale JJ, Maes D: Clean intermittent self-catheterization: a 12-year follow-up. J Urol 1990; 143: 906-908.

- Goepel M, et al: Intermittent self-catheterization. Results of a comparative study. Urologist 1996; B 36: 190-194.

- Piechota, HJ, Pannek J: Catheter drainage of the urinary tract – state of the art and perspectives. Urologist 2003; 42: 1060-1069.

CONCLUSION FOR PRACTICE

- The transurethral indwelling bladder catheter, the most common type of catheter, is frequently associated with complications, particularly urinary tract infections.

- The risk of infection increases with recumbency and is greater in women than in men.

- If the patient stays five days or more, the bladder should be drained suprapubically. Urinary tract infections and problem germs occur later and less frequently with the suprapubic compared to the transurethral catheter.

- Compared to the transurethral and also suprapubic bladder catheter, intermittent catheterization is by far the alternative with fewer complications for catheter drainage of the urinary bladder in cases of bladder dysfunction.

A RETENIR

- Le cathéter vésical transuréthral permanent comme type de cathéter le plus répandu est souvent associé à des complications, en particulier à des infections des voies urinaires.

- Le risque infectieux augmente avec la durée de l’alitement et est plus élevé pour les femmes que pour les hommes.

- Pour une durée de l’alitement de cinq jours et plus, la vessie doit être drainée par voie suprapubienne. Les infections des voies urinaires et les souches problématiques surviennent plus tard et plus rarement par voie suprapubienne en comparaison avec le cathéter transuréthral.

- En compararaison avec le cathéter transuréthral et également avec le cathéter suprapubien le cathétérisme intermittent représente l’alternative qui entraîne le moins de complications pour le drainage de la vessie par cathéter en cas de troubles de la fonction urinaire.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2014; 9(4): 28-32