At Medidays, the internal medicine training program of the University Hospital Zurich (USZ), presentations were also given on various hematology topics. How is anemia meaningfully clarified? Which patients should be switched to new anticoagulants in practice? And which therapeutic measures benefit patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia?

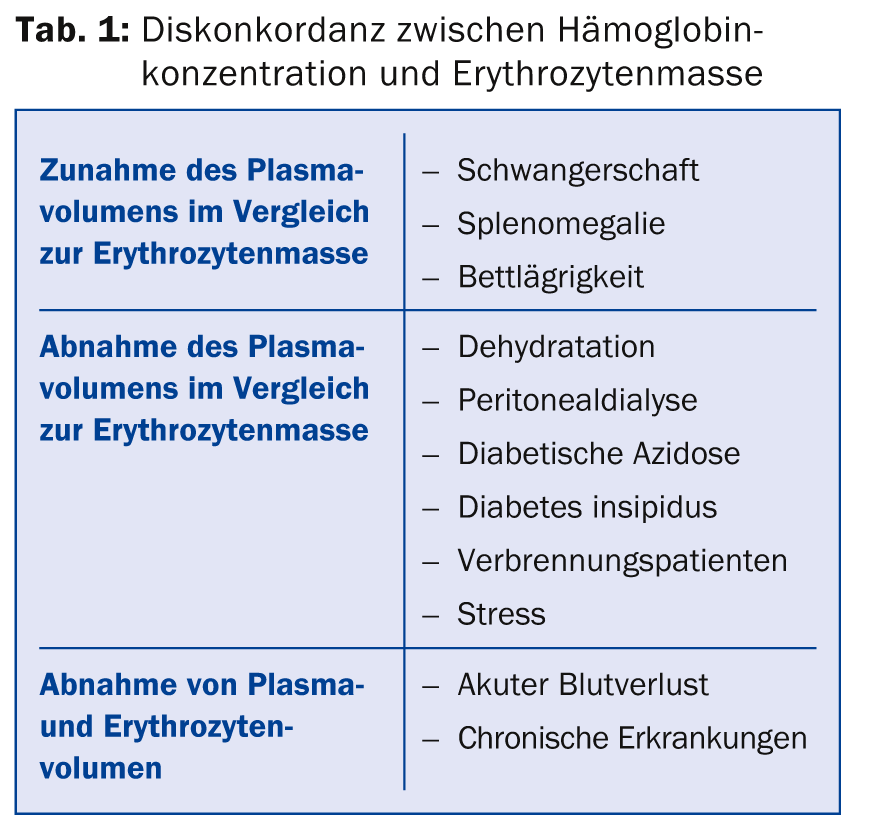

(ee) Dr. med. Jeroen Goede, Head Physician a.i. of the Clinic for Hematology at the University Hospital Zurich, provided information on the assessment and treatment of anemia. There are various causes for a discordance between the hemoglobin concentration and the erythrocyte mass (Tab. 1). In principle, the hemoglobin concentration depends on various factors such as age, sex, race and altitude of residence. The reference values for anemia in women are <120 g/l, in pregnancy <110 g/l and in men <130 g/l. The lower value in women is not due to menstruation, but to lower testosterone levels; when testosterone levels decrease in men as they age, hemoglobin concentration also decreases.

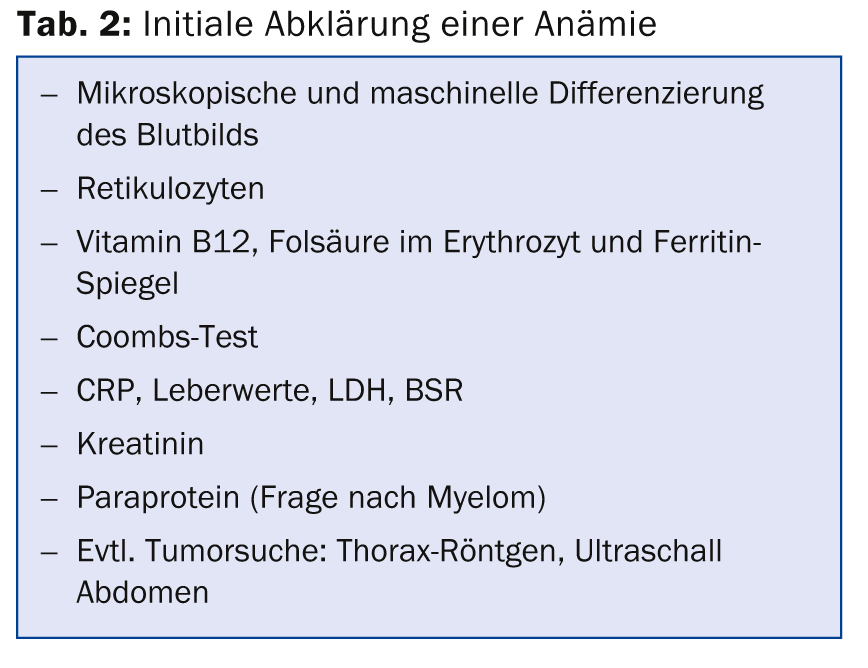

The differential diagnosis of anemia is very diverse. Basically, a distinction is made between inadequate production of erythrocytes (e.g. in iron deficiency or disturbance of normal erythropoiesis in malignancies), increased degradation (e.g. in prosthetic heart valves, autoimmune hemolytic anemias, membrane defects, etc.), loss of erythrocytes (acute or chronic hemorrhage), and “pseudo” anemia (e.g. in pregnancy). A few laboratory tests are usually sufficient for the initial clarification of anemia (Table 2). This allows the diagnosis to be made in about two-thirds of all anemias.

Iron metabolism is very complex. In 99% of cases, however, ferritin determination is sufficient to diagnose iron deficiency anemia; a complete iron status is usually unnecessary. In case of iron deficiency, patients should be advised to eat a diet rich in iron (meat, egg yolk, cereals with husks, soy, nuts, wholemeal bread). Oral iron substitution with 200 mg/d ferrous sulfate (over 3 – 6 months) is only useful if the iron can also be absorbed – this is why, for example, iron substitution should be given i.v. in the case of celiac disease. However, iron tablets not infrequently cause gastrointestinal discomfort.

Intravenous iron substitution can be performed very safely today; the new preparations with iron carboxymaltose (Ferinject®) resp. Iron sucrose (Venofer®) no longer contain dextran and no longer cause severe anaphylaxis. A clear indication is nevertheless mandatory for intravenous iron administration. These include documented intolerance of oral iron administration, malabsorption, or malcompliance that cannot be influenced. Mild thrombocytosis (up to 700 G/l) is common with iron deficiency, but usually resolves after substitution.

New oral anticoagulants

New oral anticoagulants have been available for a few years: the direct thrombin antagonist dabigatran (Pradaxa®) and the direct factor Xa antagonists rivaroxaban (Xarelto®), apixaban (Eliquis®) and – not available in Switzerland – edoxaban (Lixiana®). Jan-Dirk Studt, MD, Senior Physician, Clinic for Hematology, University Hospital Zurich, presented the possible applications as well as advantages and disadvantages.

All new oral anticoagulants (NOAKs) are approved in Switzerland for embolic prophylaxis in atrial fibrillation. Rivaroxaban and apixaban are additionally approved for the prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism (VTE) during major orthopedic surgery of the hip and knee, and rivaroxaban can be used in addition for acute VTE therapy and secondary prophylaxis (without prior administration of low-molecular-weight heparin).

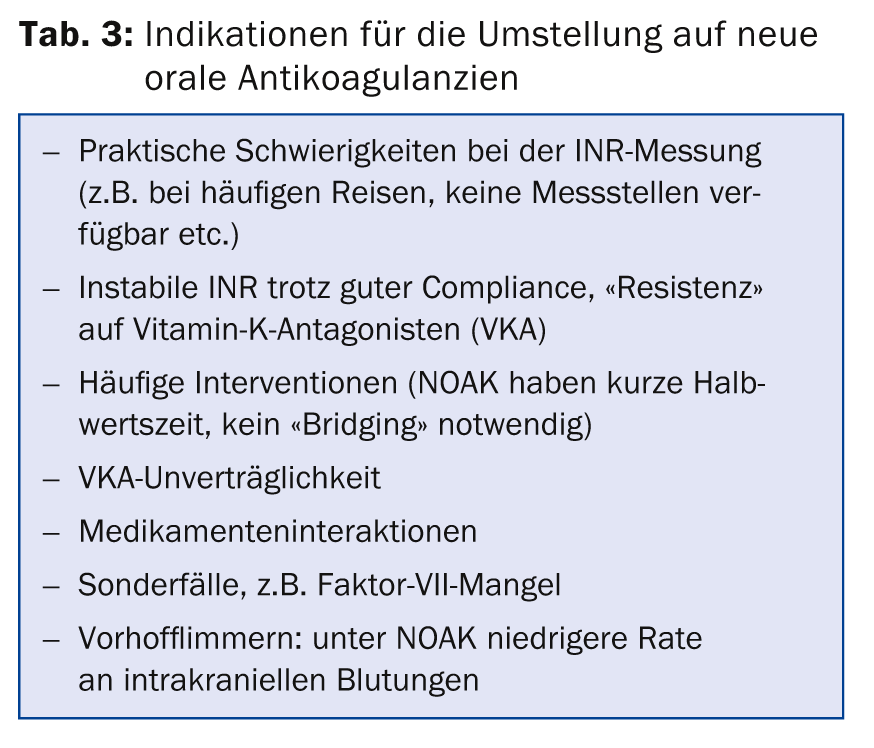

In patients with atrial fibrillation, current studies suggest that NOAKs are slightly better than vitamin K antagonists in terms of efficacy and safety; in patients with VTE, both classes are currently considered to be about equivalent. Table 3 lists the indications for conversion. In principle, NOAKs have equivalent safety and efficacy to the “old” oral anticoagulants, and a significant advantage is the rapid onset of action.

Dr. Studt provided information on the use of NOAKs in special clinical situations:

- Procedures and interventions: For most procedures, stopping NOAK is necessary at least 24 hours before the intervention, and for high-risk procedures (e.g., CNS procedures), 48 hours or more before. In renal insufficiency, a longer lead time is necessary.

- Action reversal: No specific antidotes are yet available, so the comparatively short half-life of the new substances is advantageous. In the case of dabigatran, dialysis is the best option; in the case of rivaroxaban and apixaban, dialysis is not promising because of the high protein binding.

- Bleeding: If bleeding is mild, symptomatic treatment is appropriate (local therapy, possibly postponing the next dose). In case of moderate to severe bleeding, the intake is interrupted and the patient is admitted to the hospital. The administration of protamine or vitamin K is ineffective. If necessary, prothrombin complex concentrate or activated prothrombin complex concentrate can be administered.

- Mechanical heart valves: In patients with mechanical prosthetic heart valves, vitamin K antagonists (VKA) remain the standard therapy. The results of studies comparing dabigatran with VKA were unfavorable for dabigatran. Currently, all NOAKs are contraindicated in patients with mechanical prosthetic valves.

- Pregnancy and Lactation: Data on the use of NOAKs in pregnancy and lactation are very limited and all NOAKs are currently contraindicated in pregnant and lactating women. Low molecular weight heparin remains the standard therapy.

- Renal impairment: None of the NOAKs may be prescribed in patients with severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance <30 ml/min.) or dialysis requirement. In cases of mild renal impairment, dosages may be adjusted.

- Quantification of NOAK effect is of interest in certain clinical situations, for example, before – especially unplanned – surgery, in trauma, hemorrhage, renal insufficiency, very mild or very severe patients, suspected overdose, or occurrence of thrombosis under adequate therapy. There is no target range as with VKA or heparin, and specific assays are available for quantification for each agent.

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia

Prof. Markus G. Manz, M.D., Director of the Department of Hematology, University Hospital Zurich, spoke on chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). This most common of all leukemias occurs primarily in the elderly (median age at initial diagnosis 70 years). Due to the aging of the population, the incidence of CLL will increase in the future. 7% of all healthy blood donors over 45 years of age have monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis (MBL) in their peripheral blood, but in the presence of MBL, transition to CLL occurs in only about 1-2% per year.

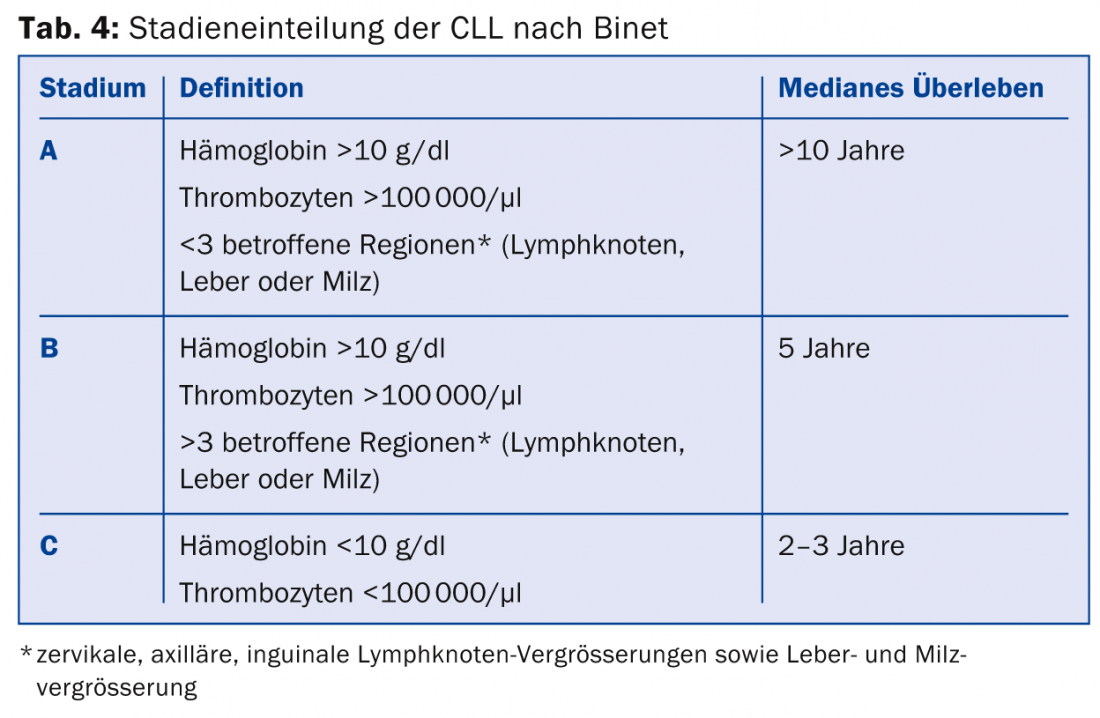

The dynamics of CLL vary greatly among patients: the disease may progress rapidly, but it may also be asymptomatic (incidental finding). Typical symptoms include a drop in performance due to anemia, infections, bleeding stigmata, B symptoms (fever, night sweats, weight loss), lymph node swelling, and swelling of the liver and/or spleen. Diagnosis is made from peripheral blood (monoclonal B lymphocytes >5000/µl); bone marrow aspiration is usually not necessary, but may be useful in individual cases, especially before starting therapy. Cytogenetic workup should always be performed to diagnose chromosomal aberrations that are prognostically unfavorable.

CLL is classified according to Binet (Table 4) or Rai, which is important for estimating prognosis. As recently as 1974, only 5% of CLL patients survived diagnosis for more than five years – this situation has changed significantly as several treatment options are available. However, CLL is not curable by systemic therapies. In asymptomatic CLL, the patient is not treated because there is currently no evidence that therapy in the asymptomatic stage provides benefit. An indication for therapy generally exists at stage Binet C or when distressing symptoms such as lymph node swelling, liver and spleen swelling, B symptoms, anemia, etc. are present.

Standard therapy today is chemotherapy with fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab (FCR). However, this scheme is deviated from depending on the age and general condition of the patient, comorbidities (especially renal insufficiency) and chromosomal aberrations. The combination of bendamustine and rituximab has been shown to be less toxic but also somewhat less effective than the FCR regimen. Therefore, this combination is more commonly used in older patients over 65 years of age. In patients with refractory or relapsed CLL, allogeneic stem cell transplantation is also possible.

In July 2014, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) recommended the tyrosine kinase inhibitors ibrutinib and idelalisib (Zydelig®) and the anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody obinutuzumab (Gazyvaro®) for approval in the indication CLL. Ibrutinib can significantly prolong survival, but resistance also develops.

The speaker drew attention to the fact that the high cost of the new drugs for treating chronic leukemias poses a challenge to society: “Treating hypertension with enalapril costs around 500 Swiss francs per year, while treating CML with imatinib costs 40,000 Swiss francs. As people grow older and chronic leukemias become more common, the question arises as to who will bear the cost of these expensive therapies.”

Source: Medidays, September 3, 2014, University Hospital Zurich

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2014; 9(11): 52-56