More than 95% of all emboli in patients with atrial fibrillation originate in the left atrial ear. Atrial appendage closure can be performed by means of a 20-minute procedure under local anesthesia and allows oral anticoagulation to be suspended immediately and platelet inhibition to be suspended after a short period of time. Modern stroke prophylaxis in patients with atrial fibrillation consists of either lifelong drug therapy using non-vitamin K-dependent oral anticoagulants (NOAKs) or one-time atrial appendage closure. Atrial appendage closure provides better stroke protection and survival benefit compared with VKA. Atrial appendage closure and NOAK have not yet been compared against each other. In certain clinical situations, atrial appendage closure appears superior to NOAKs and is the therapy of choice.

Patients with atrial fibrillation often present treating physicians with a dilemma: stroke prophylaxis using blood thinners (vitamin K antagonists [VKA] or non-vitamin K-dependent oral anticoagulants [NOAK]) is effective but exposes the patient to an increased risk of bleeding. It is therefore necessary to assess bleeding and stroke risk on an individual basis.

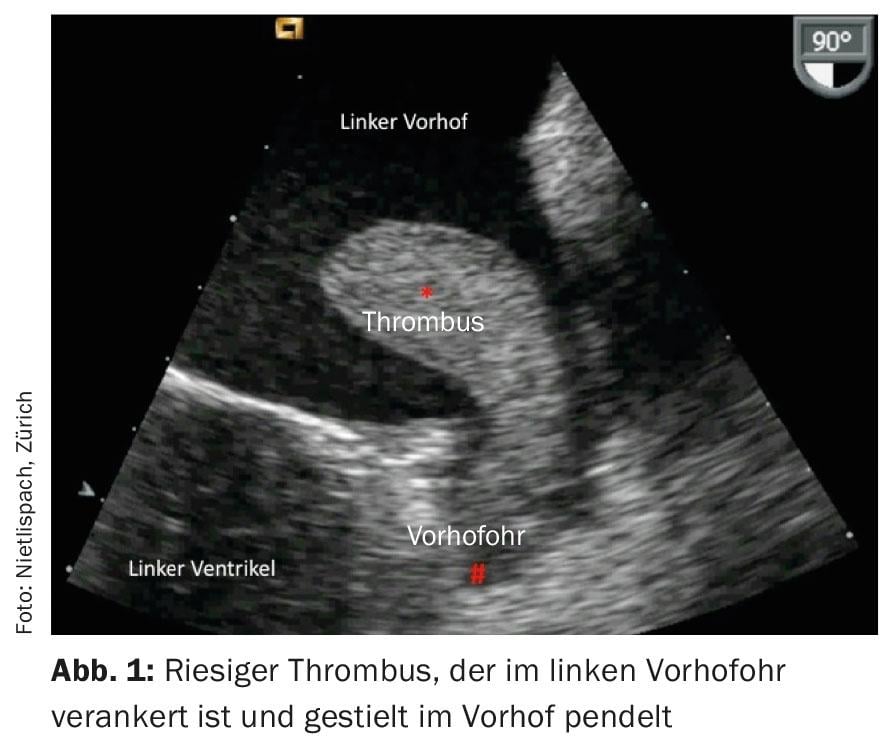

Atrial appendage closure, a somewhat lesser-known method, is another therapeutic option for stroke prophylaxis. The left atrial tube is the source of >95% of all thrombi in patients with atrial fibrillation (excluding patients with atrial fibrillation due to rheumatic mitral stenosis) (Fig. 1) . Interventional atrial appendage closure seals the entrance to the atrial appendage, achieving effective stroke prophylaxis and making oral anticoagulation with all its side effects obsolete [1]. The principle is convincing: the evil is tackled at the root and eliminated in a single intervention, which is why atrial appendage closure can also be called mechanical inoculation.

Case study

A 56-year-old patient with atrial fibrillation on rivaroxaban (Xarelto®) and additional known hypertension is admitted to the hospital with acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction. The cause of his heart attack is quickly found and repaired: An occluded right coronary artery is opened by balloon dilatation and stent implantation. This disease history, relatively simple at first glance, turns out to be more complicated at second glance. What anticoagulation regimen should be chosen for this patient?

VKA versus NOAK

Should stroke prophylaxis in patients with atrial fibrillation be given by VKA or NOAK? Three large randomized trials (ARISTOTLE, RE-LY, ROCKET-AF) have answered this question: NOAK are superior to VKA in terms of efficacy (stroke prophylaxis) as well as safety (prevention of bleeding) [2–4]. Dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban reduced stroke risk by 20-30% compared with VKA in patients with AF. Thus, these blood thinners are more potent than VKA and yet they reduce the risk of cerebral hemorrhage by 30-60%. However, it appears that the gastrointestinal tract in particular is somewhat more susceptible to bleeding with NOAKs (50% higher risk of severe GI bleeding with dabigatran), so caution should be exercised with NOAKs in patients who are sensitive in this regard.

VKA versus atrial appendage closure

The superiority of atrial appendage closure over VKA was impressively demonstrated in the PROTECT-AF trial [5]: After 3.8 years of follow-up, there was a significant 39% annual risk reduction for stroke, systemic embolism, and cardiovascular death in patients treated with atrial appendage closure. In contrast to the studies with NOAK, atrial appendage closure also demonstrated a mortality benefit: The risk of death was significantly reduced by 35% annually on average with atrial appendage closure; the risk of cardiovascular death decreased by 60% annually. Subgroup analyses showed a particularly clear advantage of atrial appendage closure in men and patients at low risk of stroke (mortality reduction of 55% and 71%, respectively).

The risk of experiencing a major bleed increases with oral anticoagulation with increasing age and duration of therapy. This does not apply to atrial appendage closure, because the risk of intervention is unique. It is therefore not surprising that with longer follow-up, the advantage of atrial appendage closure becomes clearer. With our long-term data, we demonstrated an even lower annual rate of neurologic events, systemic embolism, or cardiovascular death (2.5%) than in the PROTECT-AF trial [6].

Atrial appendage closure can be performed under general anesthesia and by fluoroscopy and ultrasound (especially transesophageal echocardiography [TEE]). To minimize the risks of the procedure (avoidance of general anesthesia and TEE guidance), there is an alternative to perform atrial appendage closure on the awake patient under local anesthesia and with fluoroscopy alone. The latter variant is more patient-friendly.

Because atrial appendage closure is a technically challenging procedure, complications can arise even in experienced hands. These occur in approximately 4% of patients. These are, among others

- Pericardial effusions; these can usually be treated conservatively

- Perforations of the atrial tube; in rare cases, these require emergency cardiac surgery

- Acute embolization of the atrial ohroccluder; in this case, it must be recaptured using a lasso catheter or surgically removed

- Bleeding at the puncture site with simultaneous arterial puncture

- Deterioration of renal function (usually temporary).

NOAK or atrial appendage closure?

Based on the data explained, the two treatment options (NOAK or atrial appendage closure) should be discussed with patients who have AF. Both are modern, efficient and safe therapies. There is currently no large randomized trial comparing the two therapies. Which therapy is used in an individual patient often depends on the patient: Does the patient prefer a definitive solution with a one-time intervention risk, or does he or she prefer lifelong drug therapy with a low annual risk of major bleeding (approx. 2-3%)?

Special clinical situations with advantage atrial appendage closure

In individual patients and in special clinical situations, there is, in our opinion, an advantage of atrial appendage closure; then it should be recommended.

Patient with additional indication for antiplatelet drugs: the case report described such a situation: the patient with atrial fibrillation and coronary intervention. One would gladly prescribe an antiplatelet agent in this situation. However, it is known from large studies that the combination of NOAKs and antiplatelet agents leads to significantly more bleeding. In this setting, atrial appendage closure is a particularly attractive therapeutic option.

Patient with gastrointestinal bleeding: in the RE-LY study, therapy with 150 mg dabigatran showed a 50% increased risk of major gastrointestinal bleeding. Such hemorrhages are by no means benign, but show a 10% mortality (in hemorrhages of hospitalized patients the mortality is as high as 26%). This risk can be significantly reduced by atrial appendage closure.

Patient with renal insufficiency: The sometimes stringent inclusion and exclusion criteria in the NOAK studies do not allow the results to be applied to all patients. Patients with severe renal insufficiency were excluded from said studies. This is a risk population for both stroke and major bleeding. Atrial appendage closure can reduce the (significantly increased) risk of bleeding by 60% in this population; therefore, atrial appendage closure should be the first-line therapy. However, renal toxicity of the contrast agent used in the procedure must be considered.

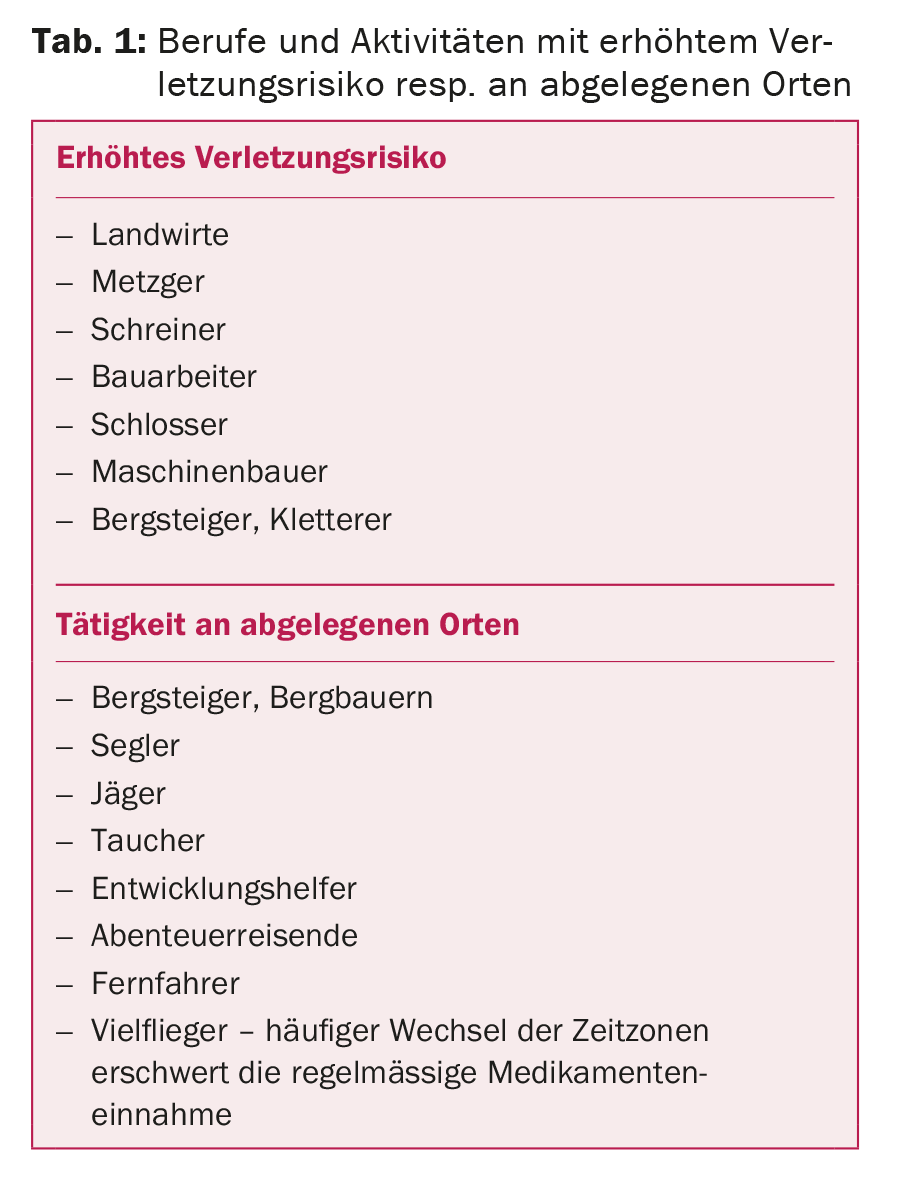

Patient with high-risk occupation or hobby: If a farmer or butcher has atrial fibrillation, atrial occlusion is also preferable to oral anticoagulation. Bleeding can also be a life-threatening problem during activities in remote locations – in Switzerland or around the world. Atrial appendage closure reduces this risk. Table 1 provides an overview of constellations that are indicative of atrioventricular occlusion.

Patient with poor compliance: drug therapy requires good medication compliance. This applies in particular to VKA, but also to NOAK. Therefore, in patients with poor compliance or those on many medications (and the added risk of drug interactions), atrial appendage closure is preferable. Although many patients require lifelong therapy with acetylsalicylic acid or another antiplatelet agent after atrial appendage occlusion. However, these therapies are more consistent with poor compliance.

Conclusion

Based on current data, atrial appendage closure must be considered first-line therapy. In patients with a contraindication to oral anticoagulation, it represents the only possible stroke protection. In patients without contraindication to oral anticoagulation, atrial appendage closure is superior to VKA and is at least an equal alternative to NOAKs.

Literature:

- Nietlispach F, et al: Percutaneous left atrial appendage closure. European Geriatric Medicine 2012; 3: 308-311.

- Granger CB, et al: Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2011; 365: 981-992.

- Connolly SJ, et al: Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2009; 361: 1139-1151.

- Patel MR, et al: Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2011; 365: 883-891.

- Reddy VY, et al: Percutaneous left atrial appendage closure vs warfarin for atrial fibrillation: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2014; 312: 1988-1998.

- Nietlispach F, et al: Amplatzer left atrial appendage occlusion: Single center 10-year experience. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2013; 82(2): 283-289.

CARDIOVASC 2015; 14(5): 7-9