The “International Classification of Orofacial Pain” (ICOP) is based on the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-3) and proposes a subdivision of facial pain syndromes into six groups. Groups four to six refer to facial pain that does not primarily originate from the teeth, the periodontium or the temporomandibular joint, such as trigeminal neuralgia and post-traumatic trigeminal-associated facial pain.

The ICOP classification, published for the first time in 2020, is intended to help better classify facial pain syndromes as a basis for adequate interdisciplinary care of affected patients. In terms of structure and content, it is closely based on the ICHD-3 classification at [1,2].

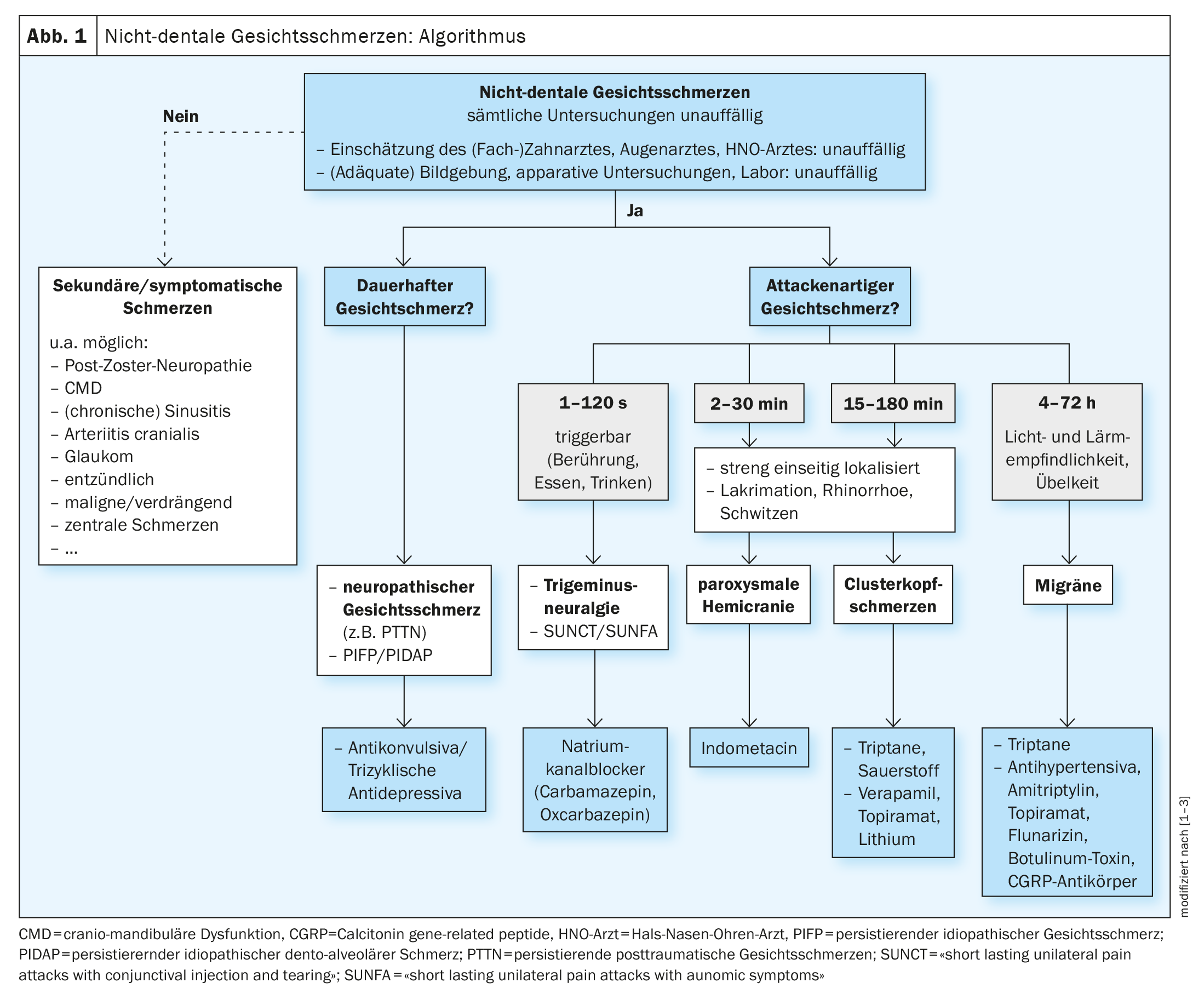

The following disorders are classified as non-dental facial pain [3]:

- Facial pain due to diseases or lesions of the cranial nerves, such as neuropathic facial pain like post-traumatic trigeminal neuropathic pain (PTTN) or trigeminal neuralgia

- Facial pain similar to primary headache syndromes, for example facial migraine or facial cluster headache

- idiopathic facial pain syndrome.

Neuropathic facial pain is defined by a lesion or dysfunction of the cranial nerves and is often described by those affected as burning, stabbing and sometimes also as attack-like [3]. Typical accompanying neurological symptoms are positive symptoms such as allodynia or dysesthesia and negative symptoms such as hypesthesia or anesthesia in the area of pain.

Antiepileptic drugs are the first choice for trigeminal neuralgia

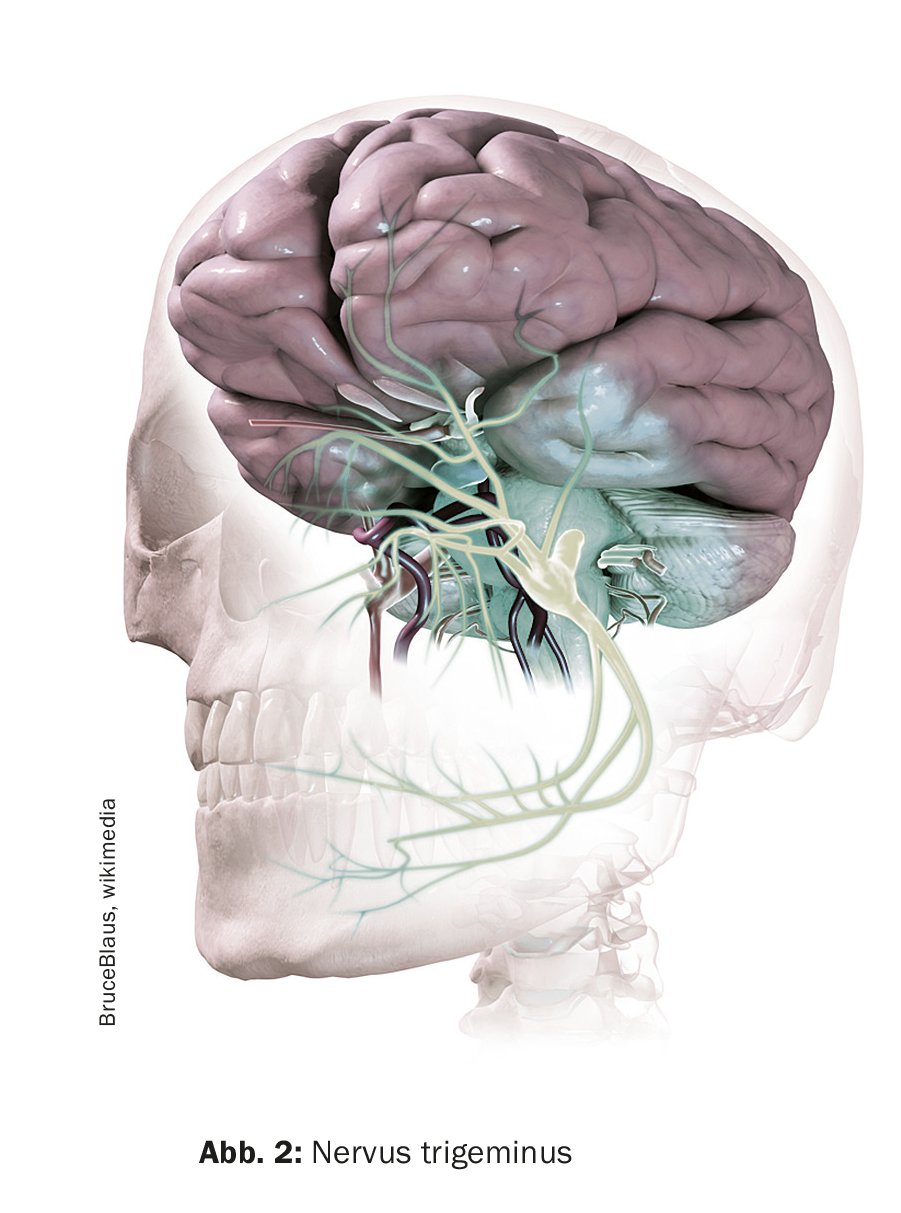

Trigeminal neuralgia is facial pain in the area supplied by the trigeminal nerve. Those affected suffer from recurring and very severe attacks of pain lasting up to two minutes, which usually occur in the upper or lower jaw area. Trigeminal neuralgia is not very common; the lifetime prevalence is 0.16 to 0.7% [4]. However, the attacks can be very stressful for those affected. Women are significantly more frequently affected than men (60%:40%). The average age of onset is 53-57 years. The cause of this pain disorder is often compression of the trigeminal nerve by a neighboring blood vessel.

Clinical features: Triggerability of the pain by touch, cold or eating and drinking is a typical feature, but not all trigeminal neuralgia is triggerable [3]. The neuralgiform, sudden onset and a duration of up to two minutes of the attacks, which are characterized by a high intensity of pain, are decisive for the diagnosis. A distinction is made between classic trigeminal neuralgia with nerve-vessel contact and an idiopathic form without an anatomical correlate, although the clinical picture is identical [5]. Both forms are distinguished from secondary trigeminal neuralgia, which is due to an underlying disease such as a space-occupying lesion or multiple sclerosis. High-resolution cMRI imaging is recommended to rule out a symptomatic cause [6].

Therapy: The anticonvulsant carbamazepine (100 mg 1-0-1; with slow dose increase to a maximum of 1200 mg/day) is recommended as first-line treatment. The initial response rate is 90% and the long-term response rate is 50% [7]. Alternatively, oxcarbazepine – also an antiepileptic drug – can be used in an initial dosage of 300 mg (1-0-1) with dose increases up to 900-1800 mg per day. The drugs of second choice are gabapentin and topiramate; combinations of these substance classes are also possible. If conservative treatment is not sufficient to bring the attacks under control, invasive microvascular decompression according to Janetta or, as a second choice, neuroablative procedures of the trigeminal ganglion can be considered as a non-drug therapy option.

What to do with persistent post-traumatic facial pain?

For the diagnosis of persistent post-traumatic facial pain (PTTN), the history of neuropathic pain must be traceable to a traumatic event of a mechanical, chemical or thermal nature that occurred no more than six months before the pain developed [2]. Women are more frequently affected and the age of onset is usually between 45-50 years; in addition, psychosocial stress is more common. Trigeminal involvement can be caused by trauma, inflammation, tumor or surgery [3]. Once the wound has healed from the initial trauma, pain symptoms develop with a slight delay – typically within six months of the trauma and persisting for more than three months.

Clinical features: The pain is constant, occasionally additional paroxysms are described. The character of the pain is burning, stabbing or pressing and can reach a high intensity. The criteria for differentiation from idiopathic persistent facial pain are positive and/or negative symptoms that can be objectified in the area of pain and indicate nerve involvement [8].

Therapy: Treatment is primarily conservative with anticonvulsants and antidepressants [3]. For the anticonvulsants, gabapentin with an initial dose of 100 mg (1-1-1) is considered first-line therapy. The dose can be increased over time up to a total daily dose of 3600 mg/day. Alternatively, pregabalin can be used, with an initial dose of 25 mg (1-2×/day), which can be increased up to 600 mg/day. Anticonvulsants have an inhibitory effect on peripheral and central nociceptive neurons and thus lead to a reduction in pain. Tricyclic antidepressants or selective serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SSNRIs) are also available as treatment options. Among the tricyclic antidepressants, amitriptyline is favored, starting with a dose of 10-25 mg (0-0-1). The dose can be increased up to 75 mg/day over time. Since the antidepressant effects of tricyclic antidepressants only start at higher doses, the analgesic effects are the main focus. The SSNRI duloxetine also has an analgesic effect by strengthening pain-inhibiting pathway systems; at the same time, an antidepressant effect is induced [9]. It is recommended to use duloxetine initially at a dosage of 30 mg (1-0-0) and to increase the dose to 120 mg per day within one to two weeks.

Literature:

- Ziegeler C, et al.: Idiopathische Gesichtsschmerzsyndrome: Übersicht und klinische Implikationen. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2021; 118: 81–87;

DOI: 10.3238/arztebl.m2021.0006 - Classification Committee of the IHS: The international classification of headache disorders. 3rd edition, ICHD-3. Cephalalgia 2018; 38: 1–211.

- May A, et al.: Klassifizierung und Therapie: Gesichtsschmerzsyndrome im zahnärztlichen Alltag: Sind’s wirklich die Zähne? zm-online.de, Ausgabe 22/2022, www.zm-online.de/artikel/2022/sinds-wirklich-die-zaehne/gesichtsschmerzsyndrome-im-zahnaerztlichen-alltag, (letzter Abruf 01.11.2023)

- «Unterversorgte Kopfschmerzarten: neue Leitlinie Trigeminusneuralgie und eine oft unerkannte Kombination», Deutsche Migräne- und Kopfschmerzgesellschaft, 14.09.2023.

- Benoliel R, Gaul C: Persistent idiopathic facial pain. Cephalalgia 2017; 37: 680–691.

- Bendtsen L, et al.: European Academy of Neurology guideline on trigeminal neuralgia. Eur J Neurol 2019; 26: 831–849.

- Förderreuther S, et al.: Trigeminusneuralgie. S2k-Leitlinie, in: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Neurologie (Hrsg.): Leitlinien für Diagnostik und Therapie in der Neurologie: 2012.

- The Orofacial Pain Classification Committee: International Classification of Orofacial Pain, 1st edition (ICOP). Cephalalgia 2020; 40(2): 129–221.

- Binder A, Baron R: The Pharmacological Therapy of Chronic Neuropathic Pain. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2016; 113: 616–625.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2023; 18(11): 36–37

InFo NEUROLOGIE & PSYCHIATRIE 2023; 21(6): 38–39