In addition to physical symptoms, behavioral, emotional and cognitive disturbances are the main factors that play a role in the performance and quality of life of patients with multiple sclerosis. These must therefore be detected and treated at an early stage.

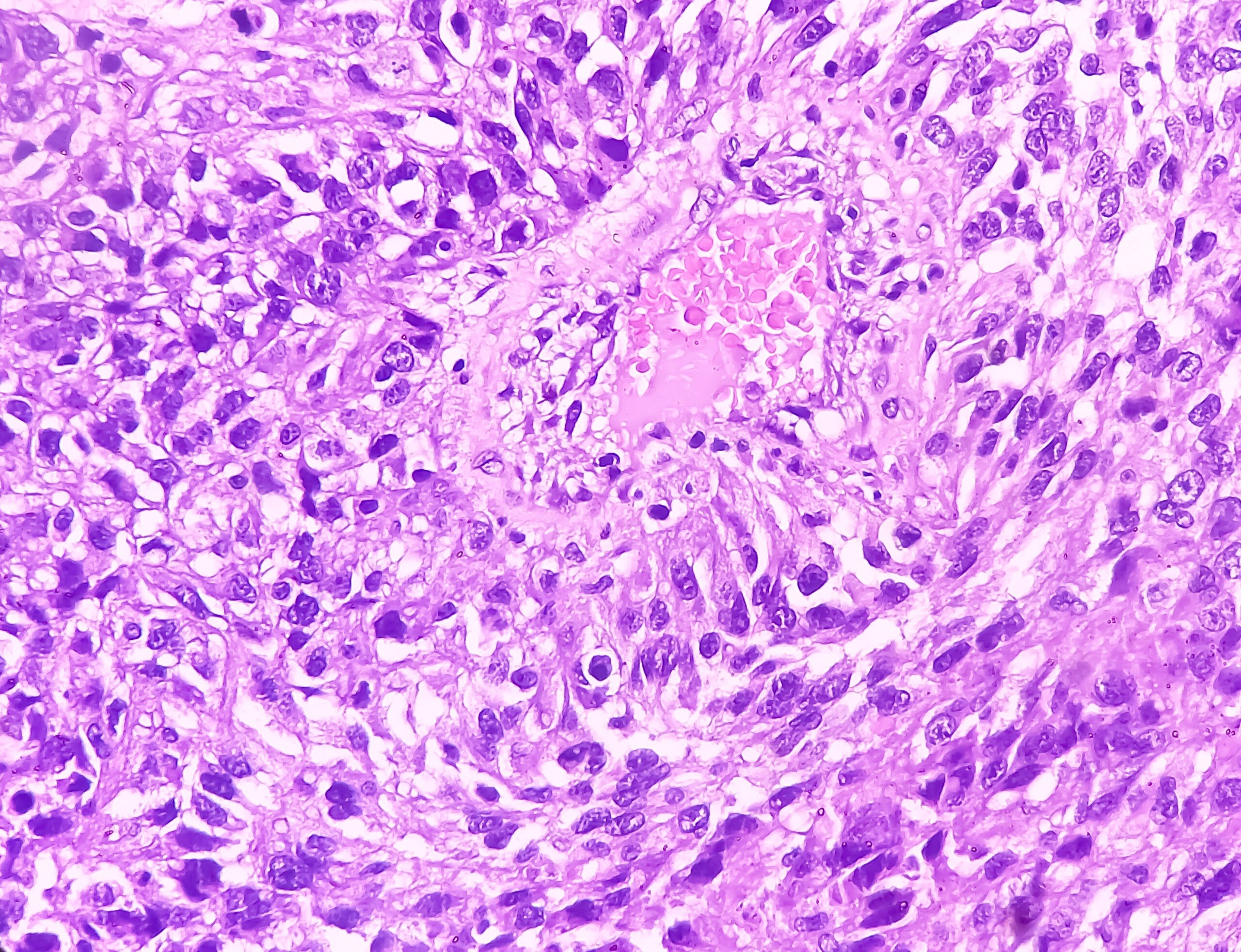

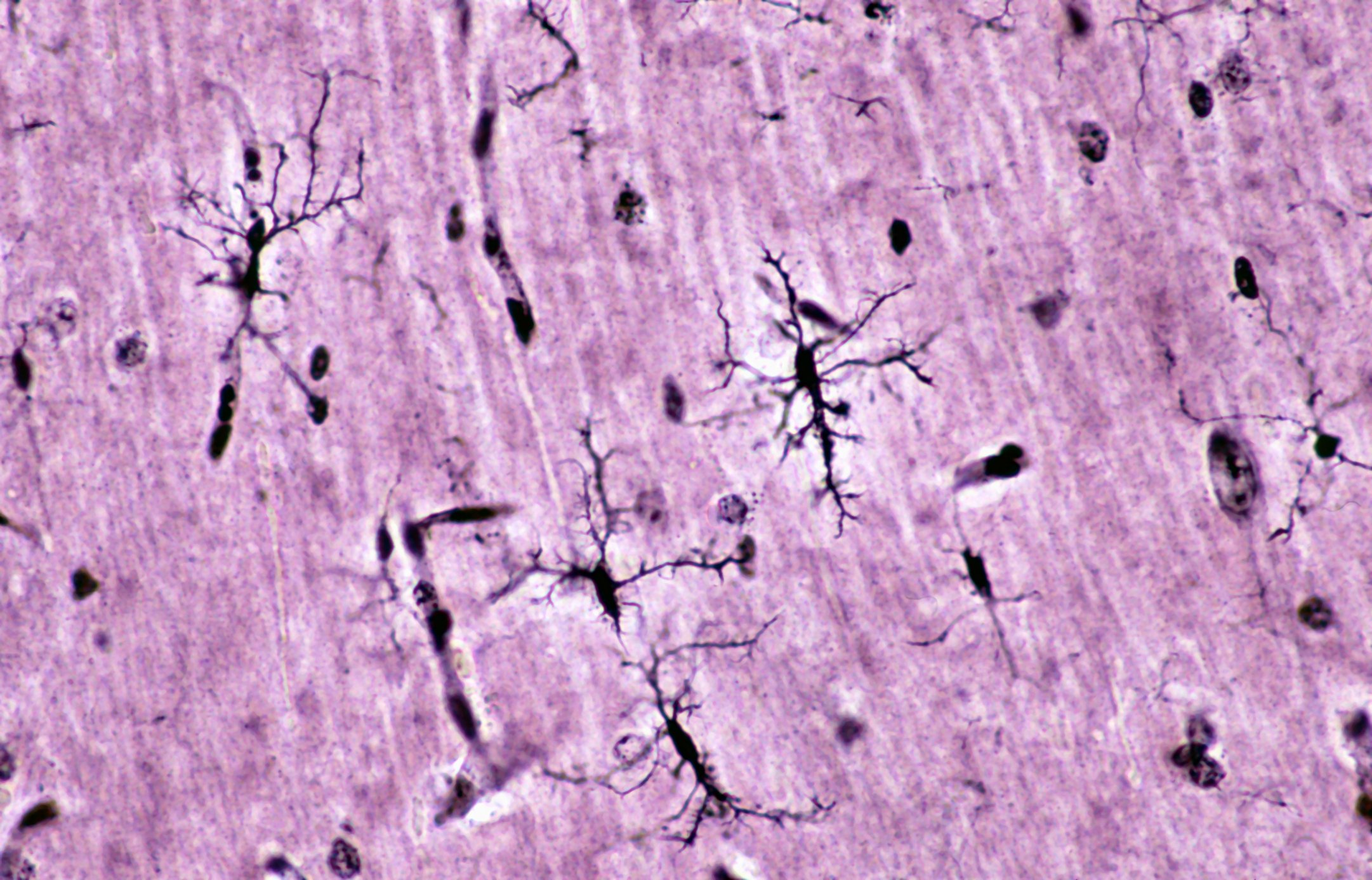

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic disease of the central nervous system characterized by inflammation, demyelination and axonal loss. MS affects the gray and white matter of the brain and spinal cord, eventually leading to diffuse atrophy of the gray and white matter [1]. Behavioral, emotional, and cognitive disorders are common and diverse in MS [2-7, 23,24]. Depression is the most common neuropsychiatric symptom with a prevalence of 50%. For example, possible other manifestations in one study were lability (41%), irritability (38%), inflexibility (26%), aggression (23%), impatience (22%), apathy (22%), adjustment disorder (17%), and obsessive-compulsive disorder (15%) [2].

Both organic changes in the central nervous system and psychological aspects can lead to behavioral, emotional, and cognitive disorders. These symptoms occur for a variety of reasons: as a normal response to a chronic illness; MS-related sequelae; mental disorders present before the onset of the disease; mental illnesses that develop independently of MS; side effects of individual medications used in the treatment of MS. The latter may cause, for example, increased fatigue, depressive symptoms, decreased or increased drive, restlessness, difficulty concentrating, increased need to talk or decreased need to sleep.

Behavioral disorders

Behavioral disorders in MS patients are very common [2–8]. They can occur even in patients otherwise only slightly affected by the disease, as we were able to show in our own study. Apathy, disinhibition and executive dysfunction were detectable in a relevant percentage, up to one third of MS patients. Behavioral disturbances occurred independently of disease stage, physical disability, and cognitive impairment, but correlated with fatigue and depressive disorders [7]. In two studies by Chiaravalloti et al. and Bosso et al. with more pronounced cognitive disorders in contrast to our study was found to correlate with a relevant rate of behavioral disorders [2,8]. Behavioral disorders are reported more frequently with known MS than before MS diagnosis. Here, assessments by the affected MS patient as well as by his or her close caregiver are often consistent when apathy, disinhibition, and executive dysfunction are asked [7,8]. In the care of people with MS, it is important to recognize behavioral disorders and know that they affect lifestyle and quality of life and lead to negative effects on the social environment and the workplace.

Emotional Disorders

Different emotion disorders may occur in MS patients [3–6,9]. The lifetime prevalence of depression in MS patients is approximately 50% and represents the most commonly reported neuropsychiatric manifestation of MS [3–6,9]. The risk of developing depression is about three times higher for people with MS than for the general population, with a significantly higher tendency to become chronic. Unfortunately, depression in people with MS is often not recognized and thus goes untreated. Depression also affects the management of physical neurological symptoms. Patients report hopelessness and numbness, loss of interest, guilt, self-deprecation, and possibly physical complaints such as sleep disturbances or loss of appetite. It is not uncommon for patients to also describe feelings of panic or severe anxiety. Often these are fears about the future or about a possible progression of the disease. Symptoms such as irritability, tantrums, or mood swings may also appear suddenly or last for a long time. In recent years, the link between depression and disease activity has been increasingly recognized. Gobbi et al. for example, showed an association between the presence of depression and MS lesions in specific brain regions. Furthermore, the occurrence of depression correlates with cerebral lesion load [10].

Dealing with the initial diagnosis of MS and the associated deficits is not infrequently characterized by despair and hopelessness. Suicidal thoughts are therefore common. However, Muller et al, McAlpine et al, and Schwartz et al found no increased number of successful suicides in MS patients and Kurtzke et al found one suicide among 122 deaths in MS patients, Sadovnick et al found 13 suicides among 80. In an Israeli study, the incidence of suicide in MS patients was 14 times higher than in the normal population. The suicides occurred within a few years of diagnosis or in association with a relapse or progression of MS [11–16].

In addition to depression, euphoria can also occur. This is characterized by carefreeness, optimism and subjective well-being. As a result, patients lack insight into their actual disease situation. This may result in refusal of treatment recommendations, failure to comply with the driving ban, etc.

Pathological laughing or crying may also occur in MS patients. The prevalence is up to 10% in older studies. Probably underlying this symptom is a disruption of the corticobulbar pathways. It is more common in chronic advanced MS, is associated with mild cognitive impairment, and indicates a poor prognosis. Pathologic laughter or crying as an initial symptom is rare in the relapsing phase of MS, but may occur in strategically ill-localized, i.e., pontine, lesions [17].

Cognitive disorders

Cognitive impairment is common in MS patients, with prevalence ranging from 43% to 70%, depending on the study and study population. Cognitive impairment is easier to measure and quantify than behavioral and emotional disorders and is more frequently recognized [3–6,9,18–20]. The most commonly affected cognitive areas are processing speed of information, as well as memory, attention, visual spatial processing, and executive function. In a paper by Schifferdecker et al. [9]. cognitive symptoms such as a reduction in intellectual performance, memory and concentration impairment were more likely to be disorders of chronic advanced MS. The etiology of objective and subjective cognitive impairment in MS is complex and not fully understood. Studies have shown that objective cognitive impairment in MS patients is associated with atrophy of cortical and deep gray and white matter. Researchers have postulated that this causes disruptions in connectivity between brain regions, resulting in cognitive impairment [21,22].

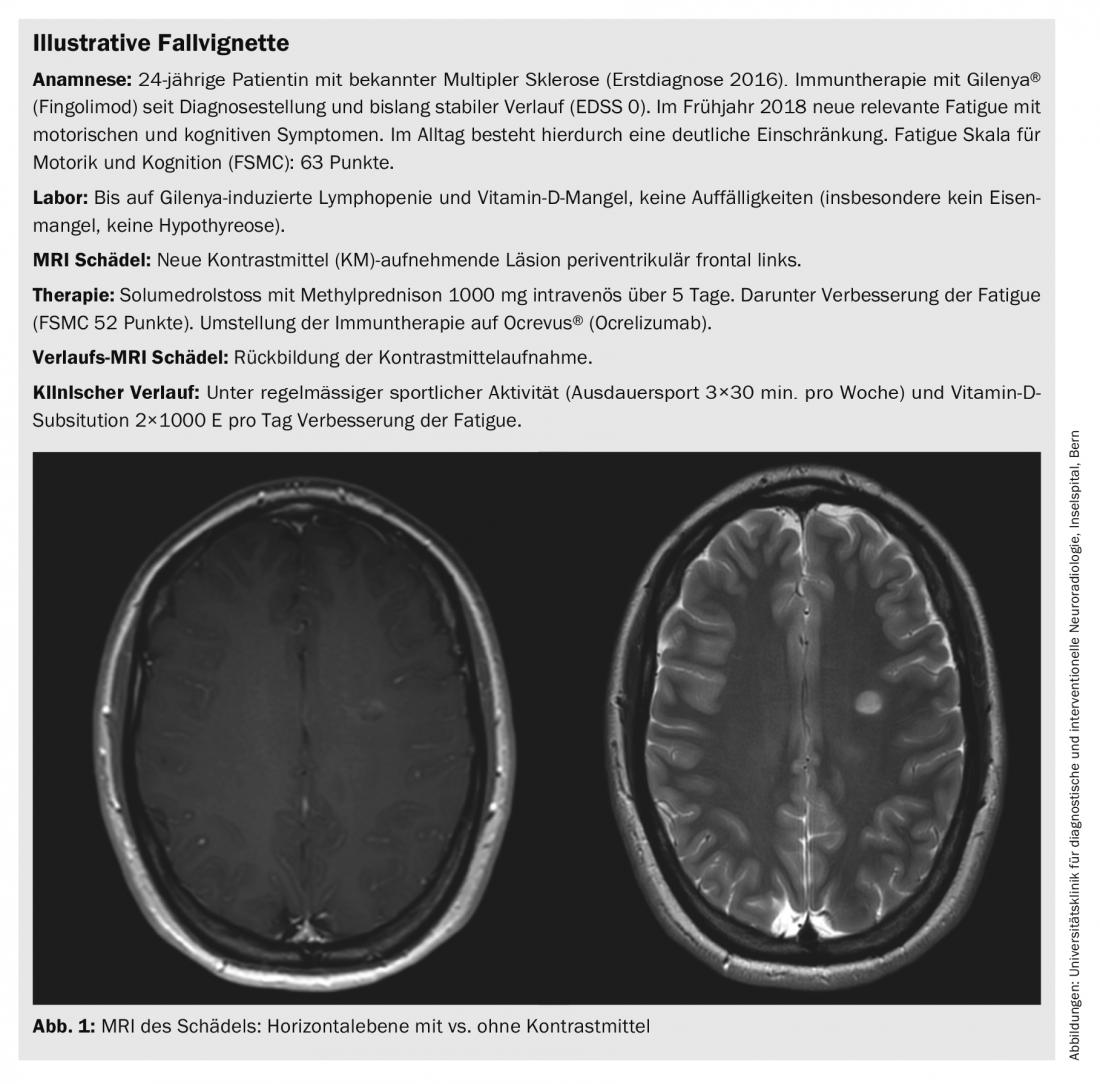

An important symptom, often underestimated by the environment, is fatigue (case vignette, Fig. 1), which affects a large proportion (about 60 to 80%) of MS patients. Fatigue is often the first and leading symptom of MS. Fatigue can be physical and/or cognitive in nature [10]. Cognitive disorders with/without fatigue can reduce performance so significantly that patients may be unable to work and have difficulty managing their daily lives. Patients also do less, for example, due to exhaustibility, which can lead to social withdrawal and depressive symptoms.

General effects

Behavioral, emotional, and cognitive disorders have a relevant impact on lifestyle and quality of life, as well as on the social environment and the workplace. Herberter et al. investigated the impact of MS on relationships. Almost 80% of people with MS report good understanding from their partner. Nevertheless, many patients describe a strain on their relationship due to MS. As disability increases, MS patients become more dependent on their partners, and couples face the challenges of changing family roles. Additionally, in 57% of cases in one study, the professional careers of close family members were negatively impacted, and the living standards of patients and their families declined by 37% since MS diagnosis [23].

Diagnostics

Behavioral, emotional, and cognitive disorders cannot be detected and specifically tested in the physical examination usually performed. For example, the Frontal System Behavior Scale (FsBS) quantifies behavioral changes associated with frontal lobe disorders, such as apathy, disinhibition, executive dysfunction. Depressive disorders can be quantified with the Beck Depression Index II (BDI II) and fatigue with the Fatigue Scale for Motor and Cognitive (FSMC) or the Fatigue Scale (FS). There are several test batteries for the assessment of cognitive disorders [7].

Therapeutic measures

Drug treatment of emotion disorders is no different from the usual approach in patients not affected by MS. Psychotherapy, social therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, and medications are used. Medication preference is given to selectively acting serotonin and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors due to their favorable side effect profile and low interaction potential. Antipsychotics may also be used. MS patients are often very sensitive to these drugs; for example, dyskinesia can occur with low doses of antipsychotics. Therefore, the use of atypical neuroleptics is preferable. A slow dosage is also recommended. Coming to terms with the illness and, in particular, the significantly increased risk of suicide often make psychotherapy necessary. Meta-analyses demonstrated the effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of emotion disorders in MS patients [24]. Close cooperation between general practitioners, neurologists, psychologists, psychiatrists and affected persons, including the relatives, is ideal. The latter are also affected by the consequences of the disease.

In the case of behavioral and cognitive disorders, neuropsychological care and occupational therapy in particular can be applied therapeutically. In this context, a combination of restorative and compensatory therapy methods seems to be particularly successful [25]. Restorative therapy procedures can also be carried out by the patient himself (e.g. PC-based), whereas compensatory therapy procedures usually have to be mediated by a therapist. For example, there are established and published methods for improving memory functions and planning skills [26,27]. In case of fatigue, regular endurance sports are also recommended.

Take-Home Messages

- MS is a previously incurable chronic disease that can have a negative impact on social and professional life.

- In addition to physical symptoms, behavioral, emotional, and cognitive disturbances significantly affect performance and quality of life. Therefore, it is important to recognize them and initiate therapeutic measures.

- Various validated diagnostic tools are available. As treatment measures, a multimodal approach incorporating medication and behavioral therapy components has proven helpful.

Literature:

- Kamm CP, Uitdehaag BM, Polman CH: Multiple sclerosis: current knowledge and future outlook. Eur Neurol 2014; 72: 132-41.

- Basso MR, et al: Self-reported executive dysfunction, neuropsychological impairment, and functional outcomes in multiple sclerosis. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 2008; 30: 920-930.

- Feinstein A, et al: The Clinical Neuropsychiatry of Multiple Sclerosis. 2nd ed. New York: Cambridge University Press 2007.

- Grigsby J, et al: Prediction of deficits in behavioral self-regulation among persons with multiple sclerosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1993; 74: 1350.

- Paparrigopoulos T, et al: The neuropsychiatry of multiple sclerosis: focus on disorders of mood, affect and behaviour. Int Rev Psychiatry 2010; 22: 14-21.

- Rosti-Otajärvi E, et al: Behavioural symptoms and impairments in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mult Scler 2012; 19: 31-45.

- Heldner MR, et al: Behavioral changes in patients with multiple sclerosis. Front Neurol 2017; 8: 437.

- Charavalloti ND, De Luca J: Assessing the behavioral consequences of multiple sclerosis: an application of the Frontal Systems Behavior Scale (FrSBe). Cogn Behav Neurol 2003; 16: 54-67.

- Schifferdecker M, et al: Psychoses in multiple sclerosis–a reevaluation. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr 1995; 63(8): 310-319.

- Gobbi C, et al: Influence of the topography of brain damage on depression and fatigue in patients with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2014; 20(2): 192-201.

- Muller R: Studies on disseminated sclerosis with special reference to symptomatology course and prognosis. Acta Med Scand 1949; 133: 122.

- McAlpine D, Lumsden CE, Acheson ED: Multiple sclerosis. A reappraisal. 2 ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins Company 1972: 179-184.

- Schwartz MI, Pierron M: Suicide and fatal accidents in multiple sclerosis. Omega 1972; 3: 291-293.

- Hashimoto S, Paty DW: Multiple sclerosis. Dis Mon 1985; 9: 519-589.

- Kahana E, Leibowitz U, Alter M: Cerebral multiple sclerosis. Neurology 1971; 21: 1179-1185.

- Sadovnick AB, Ebers GC, Paty DW: Causes of death in multiple sclerosis. Can J Neurol Sci 1985; 12: 189.

- Swamy MN et al: Pathological Laughter, Multiple Sclerosis, Behavioural Abnormality, Med J Armed Forces India 2006; 62(4): 383-384.

- Chiaravalloti ND, DeLuca J: Cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol 2008; 7: 1139-1151.

- Labiano-Fontcuberta A, et al: A comparison study of cognitive deficits in radiologically and clinically isolated syndromes. Mult Scler 2016; 22: 250-253.

- Jongen PJ, Ter Horst AT, Brands AM: Cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis. Minerva Med 2012; 103: 73-96.

- Stenager EN, et al: Suicide and multiple sclerosis: an epidemiological investigation. JNNP 1992; 55(7): 542-545.

- Nauta IM, et al: Cognitive rehabilitation and mindfulness in multiple sclerosis (REMIND-MS): a study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMC Neurology 2017; 17: 201.

- Herbert LB, et al: Impact on interpersonal relationships among patients with multiple sclerosis and their partners. Neurodegener Dis Manag 2019; 9(3): 173-187.

- Hind D, et al: Cognitive behavioural therapy for the treatment of depression in people with multiple sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2014; 14

- Rosti-Otajärvi EM, Hämäläinen PI. Neuropsychological rehabilitation for multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011; 9(11): CD009131.

- Levine B, et al: Rehabilitation of executive functioning in patients with frontal lobe brain damage with goal management training. Front Hum Neurosci 2011; 5: 9.

- Chiaravalloti ND, et al: An RCT to treat learning impairment in multiple sclerosis: The MEMREHAB trial. Neurology 2013; 81(24): 2066-2072.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2019; 17(6): 6-9.