A bicuspid aortic valve (BAK) is a common congenital heart disease. In addition to valve dysfunction, it sometimes manifests as dilatation of the aortic root or ascending aorta. This practice update provides information on diagnosis, aortic isthmic stenosis as the most common vitium, and the need for family screening.

Bicuspid aortic valve (BAK) is a common congenital heart disease and affects approximately 1-2% of the population. It was first described by Leonardo da Vinci over 400 years ago. The most common associated cardiovascular malformation is aortic isthmic stenosis (AIS), although rarer forms of congenital left ventricular outflow tract obstruction may also be associated. Dilatation of the aortic root or ascending aorta occurs in approximately 40-50% of patients with bicuspid aortic valve [1]. The extent of dilatation often does not correlate with the extent of valve dysfunction. An underlying aortopathy as well as the geometry of the bicuspid aortic valve and the associated flow characteristics have an important influence on the localization and extent of dilatation. Aortic dissections are relatively rare despite the frequently observed aortic dilatation. The most common long-term complication of BAC is the development of progressive aortic regurgitation and/or aortic stenosis. Compared with cardiac healthy individuals, the risk of endocarditis is significantly greater in patients with BAC (13.9 per 10,000 patient-years, i.e., the relative risk is increased by a factor of 11.4 compared with the normal population) [2].

Accordingly, good patient education and dental hygiene are important, whereas antibiotic shielding during dental procedures (endocarditis prophylaxis) is now only recommended in patients who have undergone prosthetic valve replacement or who have experienced endocarditis. Occasionally, surgery must be performed during childhood. In bicuspid aortic valves, degeneration of the valve with the need for aortic valve replacement occurs on average one to two decades of life earlier than in people with degeneratively altered tricuspid aortic valves. However, the age range at the time of indication for surgery is wide. Aortic valve reconstruction or replacement does not “cure” the bicuspid aortic valve, and affected patients require lifelong cardiac follow-up. Because bicuspid aortic valves run in families, echocardiographic screening of all first-degree relatives is recommended.

Diagnosis

Bicuspid dysplastic aortic valves are diagnosed in utero, shortly after birth, or in childhood, depending on the severity of valve dysfunction (usually stenosis). In critical aortic stenosis, hemodynamic instability often occurs immediately after birth, whereas in less severe valve dysfunction, the typical heart murmur usually leads to diagnosis. In patients with bicuspid aortic valves with normal valve function, an early systolic click on auscultation is often the only abnormal finding on clinical examination. Therefore, it is not uncommon for the bicuspid aortic valve to be an incidental echocardiographic finding. In asymptomatic patients with dysfunction of the bicuspid aortic valve, abnormal auscultation findings or clinical findings often lead to the diagnosis.

In the concomitant presence of aortic isthmic stenosis (approximately 6% of patients with bicuspid aortic valve [3]), the clinical signs of aortic isthmic stenosis (arterial hypertension of the upper half of the body and blood pressure difference between arms and legs), attenuated femoral pulses, or, in pronounced forms, severe heart failure lead to the diagnosis. Depending on the collective, patients with aortic isthmic stenosis are also diagnosed with a bicuspid aortic valve in approximately 50% of cases [4]. Adolescents and adults may also present with coarctation syndrome – the combination of aortic isthmic stenosis, bicuspid aortic valve, and aneurysm of the ascending aorta.

Other congenital heart malformations are also associated with bicuspid aortic valve and aortic isthmic stenosis. Worth mentioning is the Shone complex, in which, in addition to left ventricular outflow tract obstruction at various levels (subaortic stenosis, bicuspid aortic valve, aortic isthmic stenosis), the left ventricular inflow is also abnormally laid out with supravalvular membranous mitral stenosis and a dysplastic mitral valve, often in the form of a “parachute mitral valve”.

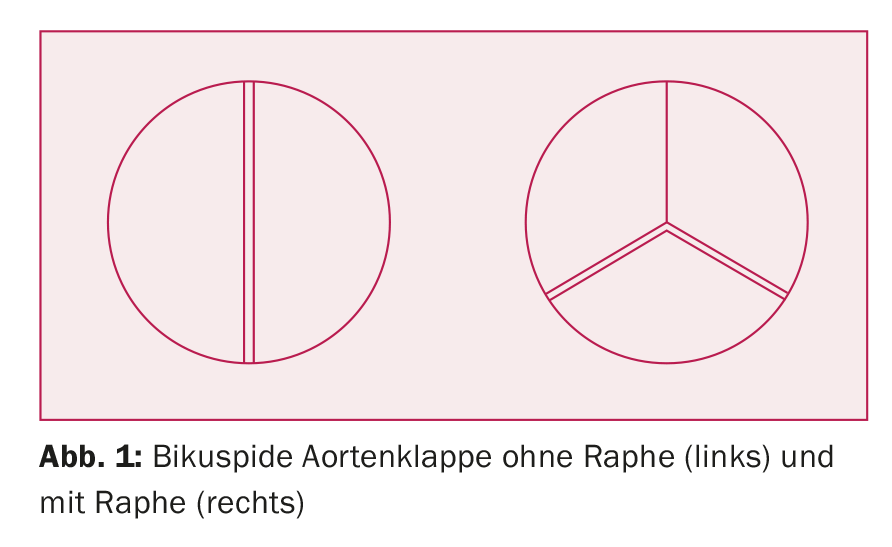

BAC is usually detected by echocardiography and occasionally discovered incidentally during a cardiac MRI scan. Diagnosis by computed tomography (CT) is more difficult because image acquisition for most indications is (end-)diastolic with the aortic valve closed. If the cuspidia cannot be clearly identified from transthoracic due to poor ultrasound windows, transesophageal echocardiography succeeds in making the diagnosis. In severely calcified valves, the distinction between bicuspid and tricuspid aortic valves can sometimes be difficult. The bicuspid aortic valve occurs in different variants: A distinction is made between “true” bicuspid aortic valves, in which the valve consists of two pockets of equal size (about 20% of all bicuspid valves), and tricuspid aortic valves, in which one (or more rarely two) pockets are fused at the commissures and form a raphe (Fig. 1). Fusion of the right and left coronary pouches is most common. If all pockets are fused at two commissures or only one pocket is formed, the valve is called a monocuspid aortic valve.

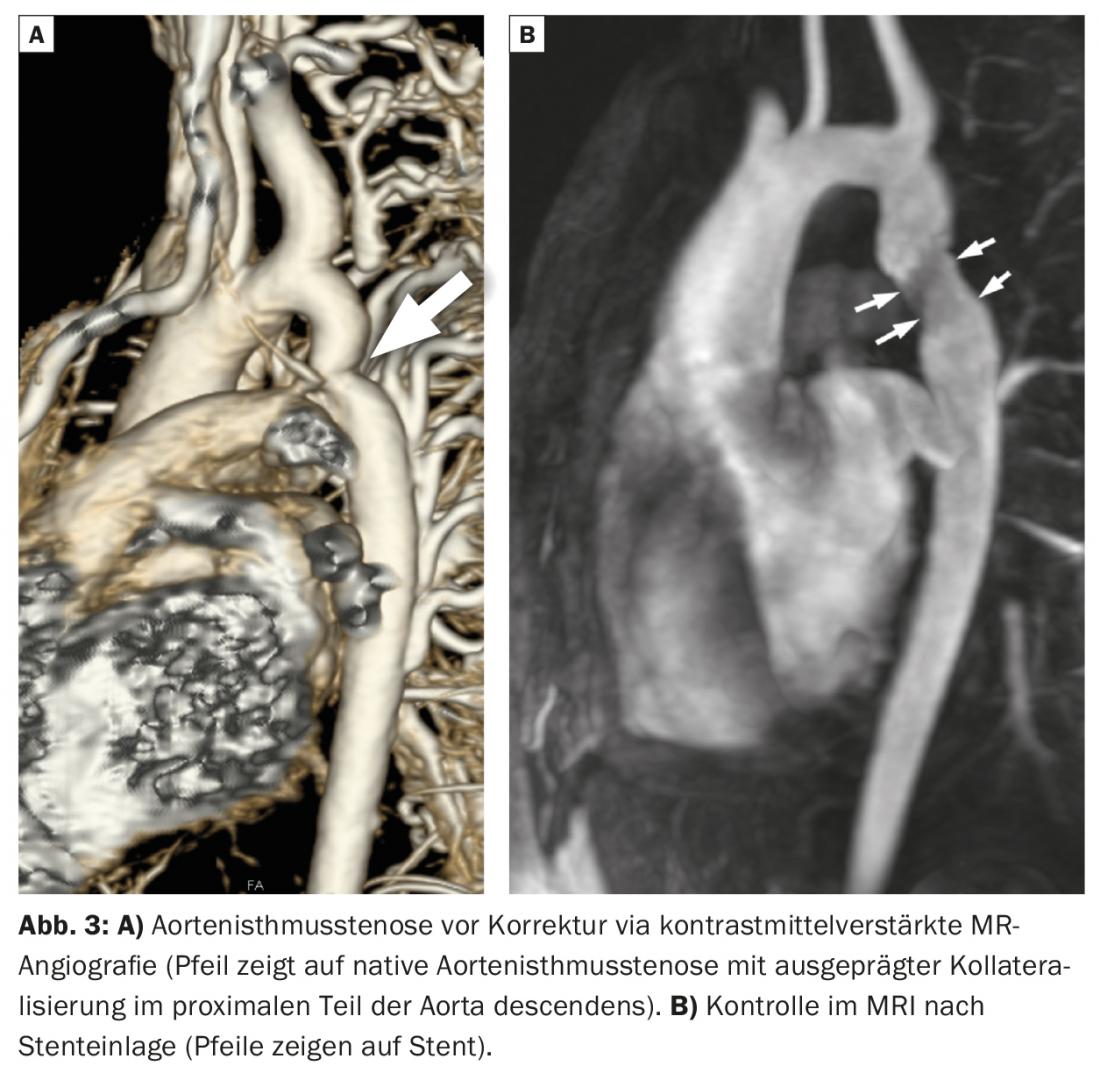

If concomitant aortic isthmic stenosis is suspected, confirmatory diagnosis by angio-MRI or angio-CT is essential. It is important to note that patients with well-developed collateral circulation are not very symptomatic, and an abnormal abdominal flow profile in the abdominal aorta is the only echocardiographic sign of the presence of aortic isthmic stenosis. It is important to consider the presence of aortic isthmic stenosis as a differential diagnosis in children or young adults with systemic arterial hypertension, as it is one of the few treatable causes of secondary arterial hypertension. The diagnosis can almost always be made with a simple blood pressure measurement of the arms and legs with evidence of a blood pressure gradient.

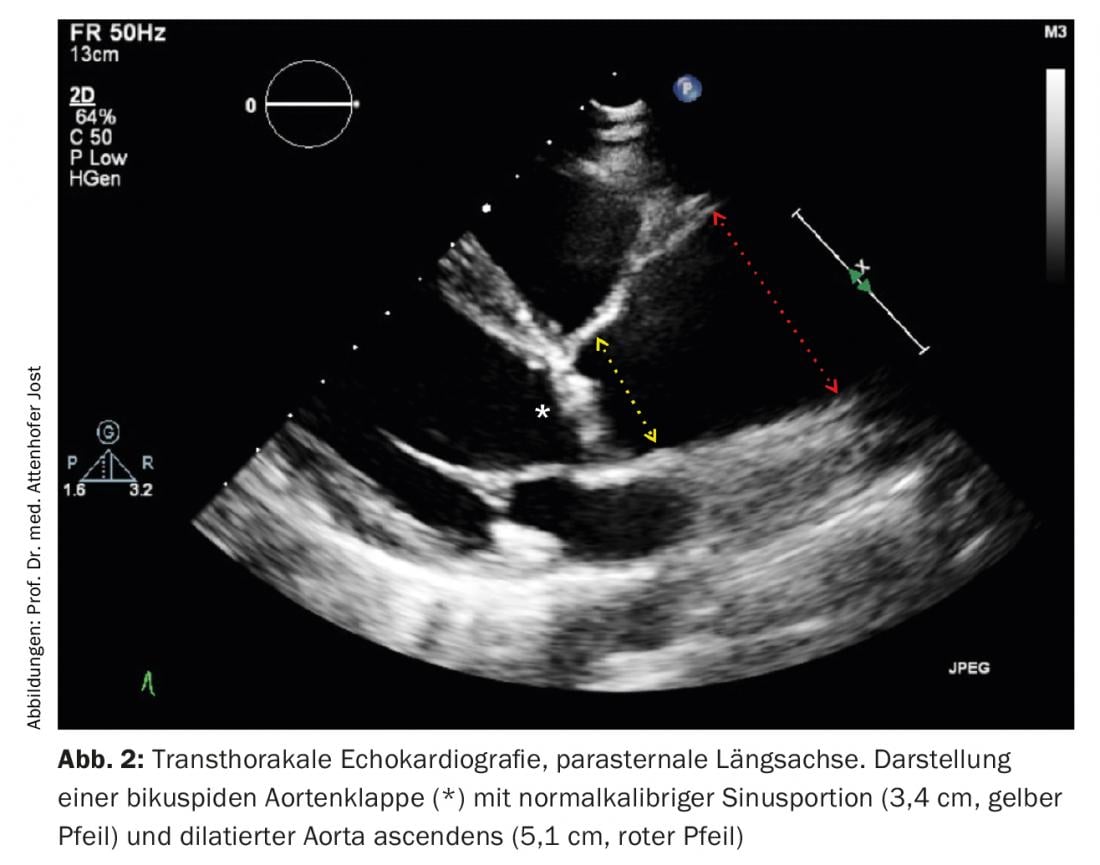

Depending on the extent and type of valve dysfunction present (aortic stenosis and/or aortic regurgitation), regular cardiac and echocardiographic follow-up examinations must be performed in asymptomatic patients to detect progression in a timely manner. This is particularly true for patients with predominant aortic regurgitation, in which symptoms often appear late in the course of the disease, when the left ventricular myocardium is already irreversibly damaged. Similarly, aortic dilatation requires regular monitoring to allow timely aortic replacement for prognostic indication in case of progression. Figure 2 shows a typical echocardiographic example of a patient with bicuspid aortic valve and aortic stenosis as well as dilatation of the ascending aorta.

Aortic aneurysm in BAC

Dilatation of the aortic root and ascending aorta, usually independent of the severity of aortic valve dysfunction, occurs more frequently in patients with BAC. According to recent patient data, the risk of dissection or aortic rupture does not appear to be greatly increased compared with patients with tricuspid aortic valves [5]. Important risk modifiers for aortic complications include nicotine abuse, inadequately treated systemic arterial hypertension, concomitant presence of aortic isthmic stenosis, or family history of dissection. Because bicuspid aortic valves are common, they sometimes occur coincidentally in patients with Marfan syndrome or other hereditary aortopathies. Therefore, if there is clinical evidence of connective tissue disease, further genetic testing is worthwhile in selected cases.

Aortic isthmus stenosis (AIS)

AIS is a narrowing in the proximal descending aorta. Typically, there is a difference in blood pressure with higher blood pressure values at the upper and lower extremities and arterial hypertension. Aortic isthmic stenosis must be treated with resection (with end-to-end anastomosis with/without patch dilation), graft replacement of the diseased aortic segment, or interventional balloon dilation and stent placement. An example of a patient with AIS before and after stent placement is shown in Figure 3. Patients with AIS are at high risk for long-term cardiovascular complications. The most common complications include systemic arterial hypertension (even with a good surgical result!), re-aortic stenosis with need for reintervention, formation of pseudoaneurysms in the area of the surgical or interventional repair site, and increased risk of cerebral aneurysms. All patients with aortic coarctation should therefore be managed at specialized centers.

Sports at BAK and AIS

Athletes with a BAC and maximum mild valvular changes and a normal-caliber aorta have no restrictions on competitive athletic activity. For athletes with a BAC and dilatation of the aorta (sinus portion/ascending aorta), depending on the extent of aortic dilatation, sports with collision potential (contact sports) and pure weight training are not recommended. During strength training, which is accompanied by a maximum isometric load, systolic blood pressure can increase up to 300-500 mmHg! If there is any uncertainty, comprehensive advice from a specialist is essential.

Follow-up of patients with BAC

Patients with a BAC occasionally require follow-up with a cardiologist with experience in this area. The control intervals depend on the degree of aortic valve dysfunction and the extent of aortopathy and must be determined on an individual basis.

In women with BAC, fetal echocardiography is recommended between the 18th and 20th weeks of gestation because of the increased hereditary risk of vitiation in the left ventricular outflow tract (in extreme cases, hypoplastic left heart syndrome). If more than mild aortic valve vitium or dilated aorta is present, comprehensive multidisciplinary consultation regarding risks of pregnancy at specialized centers is recommended.

Family screening, genetics and pregnancy

Bicuspid aortic valves run in families. Men are more often affected. A dominant mode of inheritance with incomplete penetrance is suspected. Thus, in affected patients, approximately 9-11% of first-degree relatives are also found to have BAC or, less commonly, aortic dilatation with tricuspid valve [6]. In addition, other forms of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction are more common in families with BAC, e.g., aortic isthmic stenosis and – as an “extreme variant” – hypoplastic left heart syndrome.

Thus, a family history must be obtained for each patient with heart disease. Screening of first-degree relatives is recommended. However, genetic screening is not yet routine today.

Approximately 20% of patients with congenital vitia have a syndrome (e.g. Turner syndrome, Down syndrome, DiGeorge syndrome). Indications are intellectual problems, learning problems, autism, dysmorphic facial features, short stature, or hearing and vision problems. The most common syndrome associated with BAC (and AIS) is Turner syndrome (usually monosomy X0). This should always be thought of, as in this case genetic counseling regarding offspring planning would be advisable.

If the father has aortic stenosis, the risk of congenital heart disease in the offspring is 3-4%, and 8-18% if the mother has the disease. Regarding aortic isthmic stenosis, the risk for offspring is 2-3% in affected father and 4-6.5% in mother.

Relevant aortic stenosis is poorly tolerated in pregnancy, so valve replacement should be performed beforehand. However, the question then arises whether to choose a biological valve, a mechanical valve or a Ross operation; in the latter option, the aortic valve is replaced by the patient’s own pulmonary valve with an artificial valve replacement in the pulmonary position. Long-term complications can occur with any of these variants, such as early degeneration (biological valve), anticoagulation (mechanical valve), or repetitive surgery (Ross procedure).

Risk of endocarditis

As with all congenital vitias, the risk of endocarditis is high in BAC and occurs in up to 15% of patients. 50% of cases of severe aortic regurgitation in BAC are due to occasionally unrecognized endocarditis. For diagnosis, the usual recommendations apply, such as taking blood cultures before administering antibiotics. The importance of raising awareness among patients with BAC and their primary care providers regarding typical symptoms of endocarditis and the correct workup when such symptoms occur cannot be emphasized enough.

Operations and interventions

In aortic stenosis or aortic regurgitation, the same replacement or intervention criteria apply with regard to a BAC as with the tricuspid aortic valve. However, on average, these changes occur one to two decades of life earlier. Percutaneous valve implantation in the presence of BAC is possible only in cases of aortic stenosis and in carefully selected cases. Surgery remains the treatment of choice here. If an aneurysm of the ascending aorta is present at the same time, replacement of the same is indicated. In noncalcified BAC, reconstruction, i.e., valve-preserving surgery, may be considered in selected cases.

The risks of surgery on the ascending aorta and aortic valve depend on the patient’s comorbidities, the type of surgery, and the experience of the surgical center and surgeon. In patients without additional risk factors, mortality in skilled hands is <1%, whereas emergency surgery in the setting of acute dissection carries a mortality of approximately 25% [7].

The indication and type of reintervention in patients with re-aortic isthmic stenosis should be determined at experienced centers. In cases of re-aortic stenosis, interventional treatment by stenting is preferred because of the higher risk of re-operation. However, the individual anatomy of the patient must be evaluated and the intervention planned accordingly (e.g., in cases of additional aortic arch hypoplasia or stenoses in the area of the outlets of supraaortic vessels).

Take-Home Messages

- A bicuspid aortic valve (BAK) is a common malformation of the heart and affects approximately 1-2% of the population. In addition to premature dysfunction of the bicuspid aortic valve, dilatation of the aortic root or ascending aorta often occurs.

- The most common associated vitium is aortic isthmic stenosis.

- Echocardiographic examination of first-degree family members is recommended.

- Patients with BAC are at increased risk for endocarditis and require appropriate behavioral instruction.

- Cardiac follow-up examinations for timely indication of valve and/or aortic replacement reduce the risk of serious complications (aortic dissection, irreversible cardiac dysfunction).

Literature:

- Verma S, et al: Aortic dilatation in patients with bicuspid aortic valve. N Engl J Med 2014; 370(20): 1920-1929.

- Michelena HI, et al: Incidence of Infective Endocarditis in Patients With Bicuspid Aortic Valves in the Community. Mayo Clin Proc 2016; 91(1): 122-123.

- Braverman AC, et al: The bicuspid aortic valve. Curr Probl Cardiol 2005; 30(9): 470-522.

- Dijkema EJ, et al: Diagnosis, imaging and clinical management of aortic coarctation. Heart 2017; 103(15): 1148-1155.

- Kwon MH, et al: Bicuspid Aortic Valvulopathy and Associated Aortopathy: a Review of Contemporary Studies Relevant to Clinical Decision-Making. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med 2017; 19(9): 68.

- Debiec R, et al: Genetic Insights Into Bicuspid Aortic Valve Disease. Cardiol Rev 2017; 25(4): 158-164.

- Evangelista A, et al: Insights From the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection: A 20-Year Experience of Collaborative Clinical Research. Circulation 2018; 137(17): 1846-1860.

CARDIOVASC 2018; 17(3): 20-24