Childhood asthma management is now based on close patient follow-up, including self-management education. But is it asthma at all? A question to ask yourself first. Rates of overdiagnosis are high.

A retrospective analysis of four academic centers in the Netherlands found that asthma in children aged six to 18 years was overdiagnosed in more than half of cases-with consequent unnecessary treatment and impact on quality of life [1]. “In everyday practice, there are always cases where it is not entirely clear whether the symptoms are actually due to asthma or whether there are other causes. Perhaps a child is out of breath quickly during school sports simply because he or she is overweight, or there are breathing noises due to a vocal cord dysfunction,” explained Prof. Nicolas Regamey, M.D., Pneumology, Children’s Hospital Lucerne. The latter is caused by the fact that children paradoxically close their vocal cords when breathing, i.e. they inhale “incorrectly”. In the clinic, this leads to acute onset inspiratory stridor with dyspnea on physical exertion, stress, odors, or allergens. After a few minutes, the symptoms suddenly subside. Young female adolescents are particularly affected. Therapeutically, education combined with voice exercises or speech therapy is usually sufficient.

Asthma diagnosis

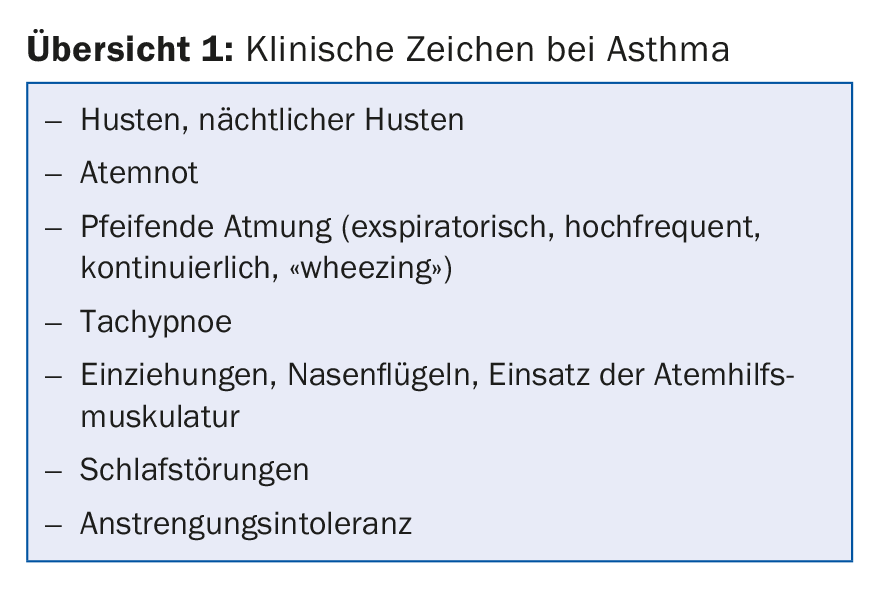

First, when diagnosing asthma, one looks for clinical signs (overview 1), plus evidence of variable/reversible bronchoobstruction (clinic, spirometry). Allergy testing or measurement of allergic airway inflammation (FeNO) is helpful, but neither specific nor sensitive.

Methacholine provocation is good for ruling out asthma, less so for confirmation. Load tests can be considered for this purpose. These are either free to perform (“free running test”), i.e. the young patient walks once around the house or climbs stairs and the physician collects subjective signs, examines clinically (shortness of breath, cough, wheezing, pulse, blood pressure), takes an SpO2 measurement and spirometry before/after. “At LUKS, we perform a standardized exercise test called the Exercise-induced Athma Test” said the speaker. Here, patients are exercised in dry air with humidity below 50% for six to eight minutes via treadmill, followed by spirometry after 5, 10, 15, (30) minutes. An FEV1 drop of 10% (15%) is diagnostic of effort asthma. “Often, young people shut down during the cooling-off period,” Prof. Regamey explained.

The differential diagnoses in asthma are diverse. As mentioned, there may simply be physical deconditioning (including obesity) or vocal cord dysfunction/breathing dyscoordination. Furthermore, one should think of banal repeated airway infections (crib attendance, tobacco smoke exposure). Postnasal drip, cough hypersensitivity syndrome (prolonged nonspecific cough), and gastroesophageal reflux are also important differential diagnoses.

Therapy goals

“So now the asthma is diagnosed, what do I want and should I treat now?” is the second question. Pharmacotherapy must be as effective, safe and simple as possible.

Efficacy: “We can’t cure asthma, that needs to be clearly communicated to parents,” Prof. Regamey advised. Basically, therapy aims to control symptoms, avoid exacerbations (as repeated episodes lead to airway remodeling), and thus prevent fixed obstruction – all with as few side effects as possible. “By no means advise a child with asthma to forgo school sports. It is important not to limit activities,” the speaker explained. Symptom control should be appropriately adjusted so that daily symptoms occur no or less than twice per week. At night, a symptom-free state should be sought so that no nocturnal awakenings occur. The use of so-called “relievers” should be limited to a maximum of two uses per week.

In this context, the SMART regimen (Symbicort® as Maintenance And Reliever Therapy) should be mentioned – a steroid (budesonide) combined with a LABA with a rapid onset of action (formoterol). Additional doses are added to the relatively low base dose (usually 2×/d) as needed (up to 6×/d from 6 years of age and 10×/d from 12 years of age). The whole thing is also possible with Flutiform®.

However, this is only at level 3 according to the level scheme of the GINA guidelines (which also applies to children). Prior to that, SABA as needed at level 1, combined with low-dose ICS from level 2 onward, are considered as controllers. The oral leukotriene antagonist montelukast is an alternative in infants and fear of steroids. In addition to the SMART regimen, the guidelines recommend moderate-dose ICS in children from stage 3 onward (primarily ages six to 11 years). In the higher stages (from stage 4), the dose of ICS combined with LABA is then further increased if the effect is insufficient.

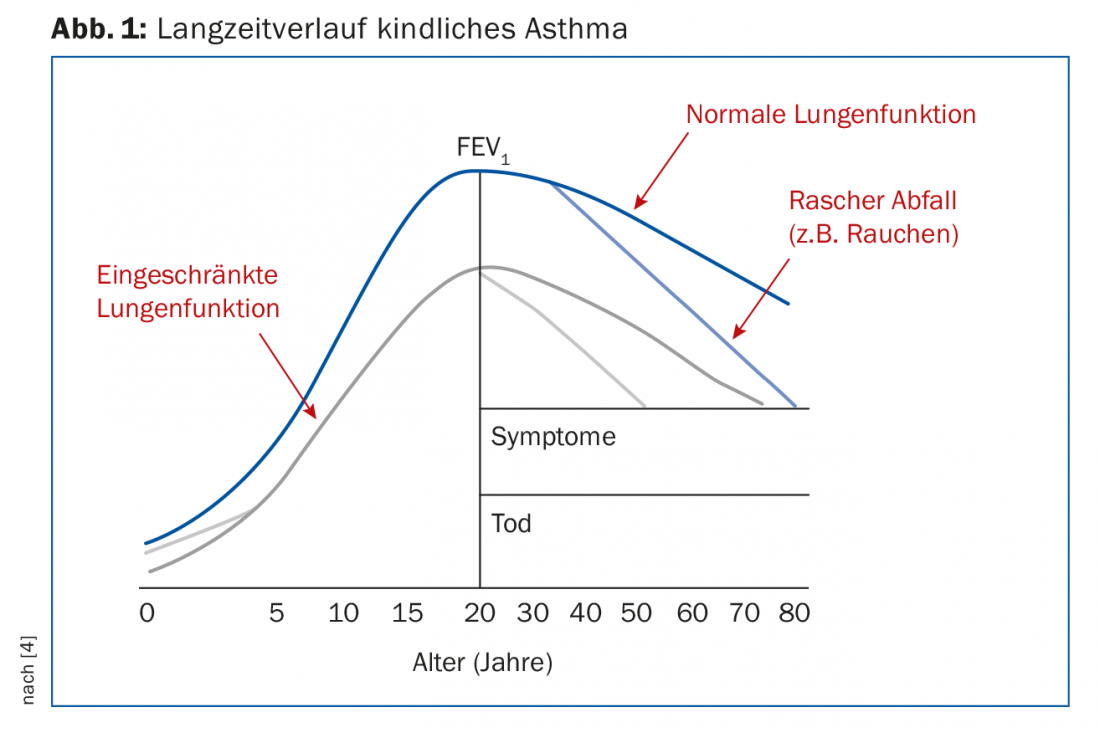

Poorly controlled asthma in childhood is a risk factor for poor lung function in adulthood. These patients therefore already start their later life with a disadvantage: The physiological decline in lung function with increasing age, but of course also harmful influences such as smoking, etc., have a disproportionately more fatal effect on them than on those who begin their adult lives with normal lung function (Fig. 1).

Safety: Corticosteroids in particular usually do not enjoy a good reputation among the general public. However, the benefits of the therapy exceed the disadvantages/side effects in many cases. A frequently discussed possible side effect in childhood is growth disturbances with a consequent reduction in body size, although according to a study with budesonide these are relatively minor (approx. -1.2 cm, especially in girls) [2]. Oral steroid-free therapy with montelukast may initially seem more attractive here, and in fact adherence may be better in certain patients who have profound reservations about ICS (including about handling). However, neuropsychiatric side effects must be considered here [3]. An unprejudiced consideration of the various treatment options with the parents and children is therefore of great importance.

Simplicity: Metered dose inhalers should always be applied with a priming chamber for children (with a mask for smaller ones). This facilitates coordination. The aerosol is decelerated after activation and remains in the chamber until inhalation. Unwanted deposits of the active ingredient oropharyngeal are reduced, but the use of these devices is rather cumbersome and requires regular cleaning (due to possible bacterial contamination). The rule is: slow and deep inhalation from the priming chamber over several breaths.

For slightly older children, but not in a severe asthma attack, dry powder inhalers may be considered. Examples are Diskus®, Turbuhaler® or Ellipta®. Coordination is not a problem here. Handling is comparatively simple, but a higher inhalation flow is required and even a small exhalation into the system can lead to clumping. The basic rule is: Inhale forcefully and deeply, then hold your breath.

“Correct inhalation needs good training and regular monitoring. Anyway, it helps enormously if children are educated about their condition, how to deal with it properly and how to self-manage it. In this context, the aha! trainings are recommended” said the speaker.

Prevention and follow-up

In addition to pharmacotherapy and patient education, optimal asthma management also includes prevention, i.e. allergen and trigger avoidance. Therefore, allergy diagnostics should not be forgotten. The biggest role is played by dust mites, which can be better addressed with targeted remediation than with desensitization. In other cases, however, it may well be indicated.

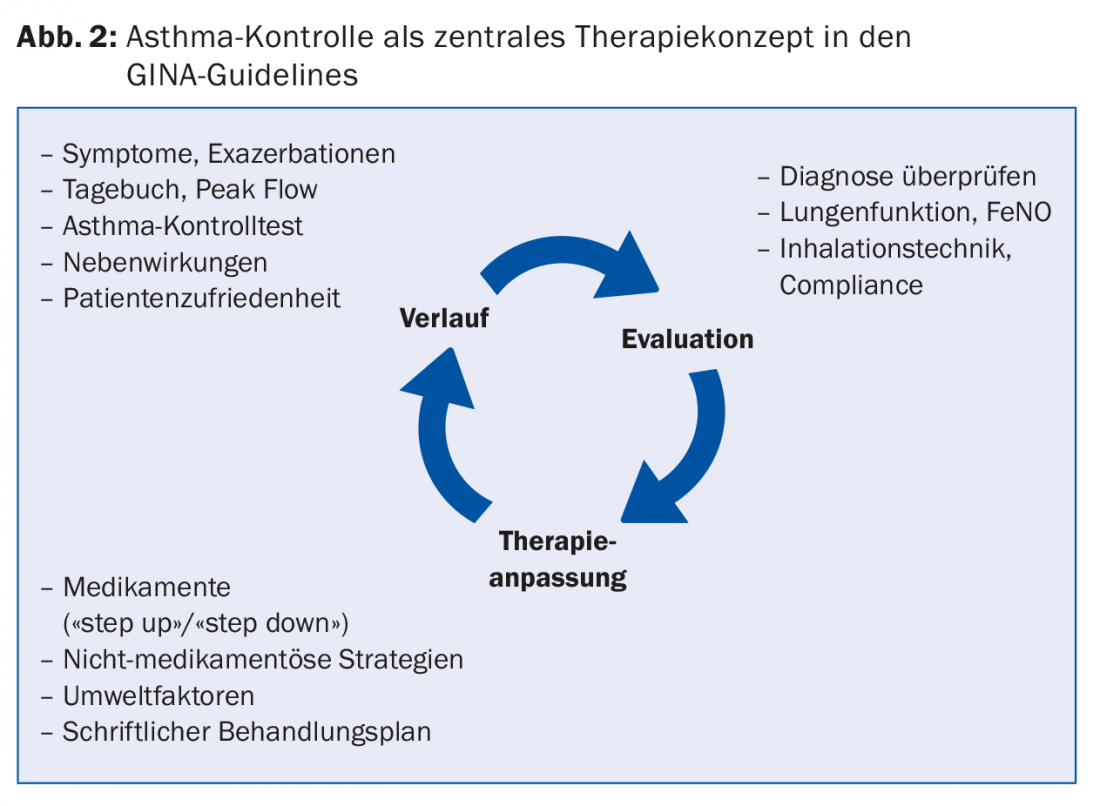

Review of non-drug strategies and environmental factors is part of the three-monthly asthma check-up (Fig. 2). Here, the course of therapy is recorded and assessed. If there is room for improvement, the drug/non-drug therapy can be adjusted and this can be recorded in the written treatment plan. The latter is helpful because children usually only listen “with half an ear” during office hours and perhaps adults are also distracted by their child’s behavior. As a reminder, the written treatment plan hangs on the refrigerator, for example, and provides information on basic therapy, reserve from physical exertion, adjustments for airway infections, and emergency therapy.

Source: 11th Spring Cycle, March 7-9, 2018, Lucerne.

Literature:

- Looijmans-van den Akker I, van Luijn K, Verheij T: Overdiagnosis of asthma in children in primary care: a retrospective analysis. Br J Gen Pract 2016 Mar; 66(644): e152-157.

- Kelly HW, et al: Effect of inhaled glucocorticoids in childhood on adult height. N Engl J Med 2012 Sep 6; 367(10): 904-912.

- Ernst P, Ernst G: Neuropsychiatric adverse effects of montelukast in children. Eur Respir J 2017 Aug 17; 50(2). pii: 1701020.

- Stocks J, Hislop A, Sonnappa S: Early lung development: lifelong effect on respiratory health and disease. Lancet Respir Med 2013 Nov; 1(9): 728-742.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2018; 13(4): 45-47