Thyroid hormones have a far-reaching effect on the body, which is why the symptoms of thyroid dysfunction are often unspecific and complex. In around 80 percent of cases, the autoimmune disease Graves’ disease is behind hyperthyroidism. The second and third most common causes are toxic thyroid autonomy and thyroiditis. The determination of TSH receptor antibodies is crucial for the further diagnostic procedure.

“Thyroid hormones are very important for metabolism in the cells,” explained PD Dr. med. Eleonora Seelig, Head Physician, Endocrinology and Diabetology, Kantonsspital Baselland [1]. “The cells function poorly if the thyroid hormones do not control this” [1]. This is noticeable when thyroid function is not euthyroid, but hyperthyroid or hypothyroid. In addition to body weight, drive and sleeping habits, bone density, skin and hair, fertility and menstrual cycle, as well as memory and concentration can also be affected. The speaker used case studies to illustrate this [1].

What are the possible causes of hyperthyroidism?

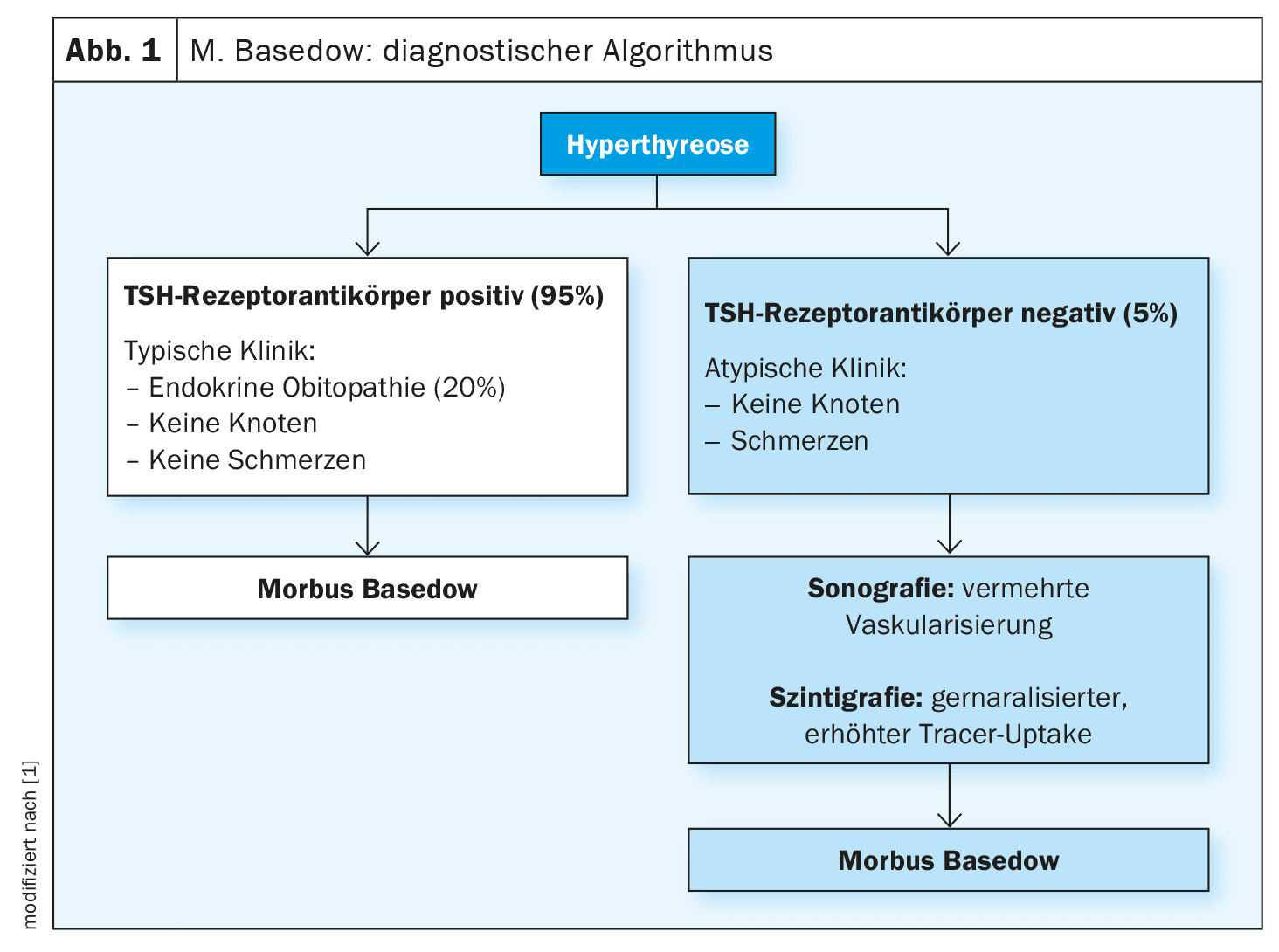

The prevalence of hyperthyroidism is reported to be ~1.3%. The spectrum of symptoms is broad, which has to do with the fact that TSH receptors are present in almost every tissue, according to Dr. Seelig [1]. In addition to increased fatigue and sweating, tremor, agitation, restlessness and sleep disturbance may occur. Defecation may be increased and patients lose body weight. Tachycardia and left ventricular atrial fibrillation are possible. And in around a fifth of cases, endocrine orbitopathy is present. The most common causes of hyperthyroidism are Graves’ disease, focal thyroid autonomy and thyroiditis. There are also drug-induced hyperthyroidism (e.g. in about 5% of patients treated with amiodarone) and cases of iatrogenic hyperthyroidism (caused by over-substitution). Iodine-induced hyperthyroidism is rare. TSH receptor antibodies are a very important tool for finding out the cause of hyperthyroidism. Depending on the case, sonography and scintigraphy can also be performed. These three methods are usually sufficient to assess the aetiology of hyperthyroidism, according to the speaker [1].

Case 1: 39-year-old with Graves’ disease

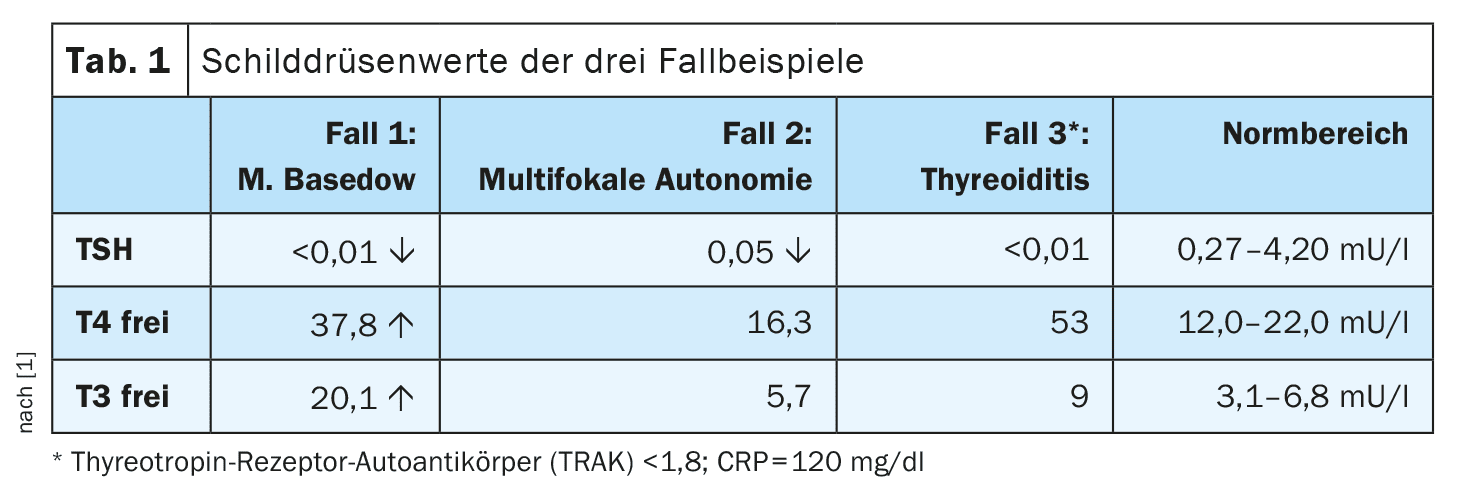

The patient consulted his GP practice due to an increasing deterioration in his general condition over the past 6 months. He was suffering from tremor, palpitations, diarrhea and had lost a lot of weight (weight reduction of 8 kg). He was also very nervous and anxious. The thyroid gland was neither palpable nor pressure dolent and no nodules were detectable. Blood pressure and heart rate values were normal (BP 138/80 mmHg; HR 102/min), body temperature was 36.7°C. He had signs of bilateral upper eyelid retraction (suggestive of endocrine orbitopathy). The results of the thyroid hormone determination are shown in Table 1. TSH was found to be suppressed, while fT3 and fT4 were elevated. “TSH is the most sensitive marker for thyroid dysfunction,” explained Dr. Seelig, adding: “80% of free thyroid hormones are T4 and only 20% are T3” [1]. This is important because T4 is not actually biologically active, but is considered a “prodrug” and reacts slowly with a half-life of 7 days. T3, on the other hand, is a biologically active hormone with a shorter half-life (1 day) and more fluctuations. T4 can be converted into T3 in the tissues. The TSH receptor antibodies were highly positive in the 39-year-old patient and he showed symptoms of endocrine orbitopathy (watery, reddened eyes; foreign body sensation; exopthalmos; periorbital edema). Overall, everything spoke in favor of a diagnosis of M. Graves’ disease.

In Graves’ disease, TSH receptor antibodies cause the thyroid gland to overproduce thyroid hormones. About one fifth of patients are affected by endocrine orbitopathy. In 95% of cases of Graves’ disease, positive TSH receptor antibodies are present and if the clinical features are indicative without palpable nodules in the thyroid gland, the diagnosis can be made without sonography and scintigraphy. In the 5% of patients without positive TSH receptor antibodies or with an atypical clinical picture, however, sonography and scintigraphy are required (Fig. 1). In Graves’ disease, ultrasound shows that the tissue is inhomogeneous and exhibits greatly increased vascularization. In scintigraphy, a generalized increased tracer uptake is a typical finding in Graves’ disease, according to the speaker [1].

Case 2: 18-year-old with multifocal autonomy

Case 2 was an 18-year-old female patient who complained of fatigue and had been experiencing hair loss and weight loss for two months [1]. The thyroid gland was not palpable and the blood pressure values were unremarkable (BP 127/83 mmHg, HR 80/min). The TSH was elevated (Table 1) and the TSH receptor antibodies were within the normal range (<1.8 IU/l) [1]. Ultrasound showed visible nodules and scintigraphy confirmed that the nodules had increased tracer uptake. A multifocal autonomy was diagnosed on the basis of the combined findings. If only one nodule is present, it is also referred to as a toxic adenoma, explained Dr. Seelig [1]. Thyroid autonomy occurs when areas of thyroid tissue are no longer under the control of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis; nodules often develop as a result. If these occur in several distinct parts of the thyroid gland, this is referred to as multifocal autonomy. If only a single area is affected, it is referred to as an autonomous adenoma or unifocal autonomy. In rare cases, the entire thyroid gland is interspersed with smaller autonomous cell islands, which is referred to as disseminated autonomy. Thyroid ultrasonography can visualize the size and structure of the thyroid nodules.

Case 3: 34-year-old woman with De Quervain’s thyroiditis

Another common form of hyperthyroidism is thyroiditis. Pathophysiologically, the overproduction of thyroid hormones is not due to the pituitary gland, but to inflammation or decay of the thyroid cells. “It is a destruction of thyroid tissue,” summarized the speaker [1]. A hyperthyroid phase often occurs initially, which can then progress to a hypothyroid phase. A distinction is made between a painful and a non-painful form of thyroiditis. The most common painful form is subacute thyroiditis (De Quervain’s thyroiditis); infections, radiation or trauma are less common causes. The most common form of non-painful thyroiditis is Hashimoto’s syndrome (also known as chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis), but there is also silent thyroiditis (e.g. postpartum, drug-induced). In Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, there is initially a hyperthyroid phase for around 1-4 months and only then hypothyroidism, explained the speaker [1].

Case 3 was a 34-year-old female patient with De Quervain’s thyroiditis. She had been diagnosed with a viral upper respiratory tract infection two weeks previously and was currently suffering from severe pain in the neck area with radiation to the jaw, as well as complaining of fever and fatigue. The patient’s thyroid gland was enlarged slightly and was full of pressure. Her body temperature was 39°C and her heart rate was 110 beats/min (tachycardia). The thyroid values revealed elevated TSH values (Table 1). In addition, the CRP was significantly elevated with a value of 120 mg/dl. This was confirmed by the typical findings on sonography: an inhomogeneous, low-echo, nodular change. In scintigraphy, a reduced tracer uptake is typical, which was also the case in the present case [1].

What treatment options are available?

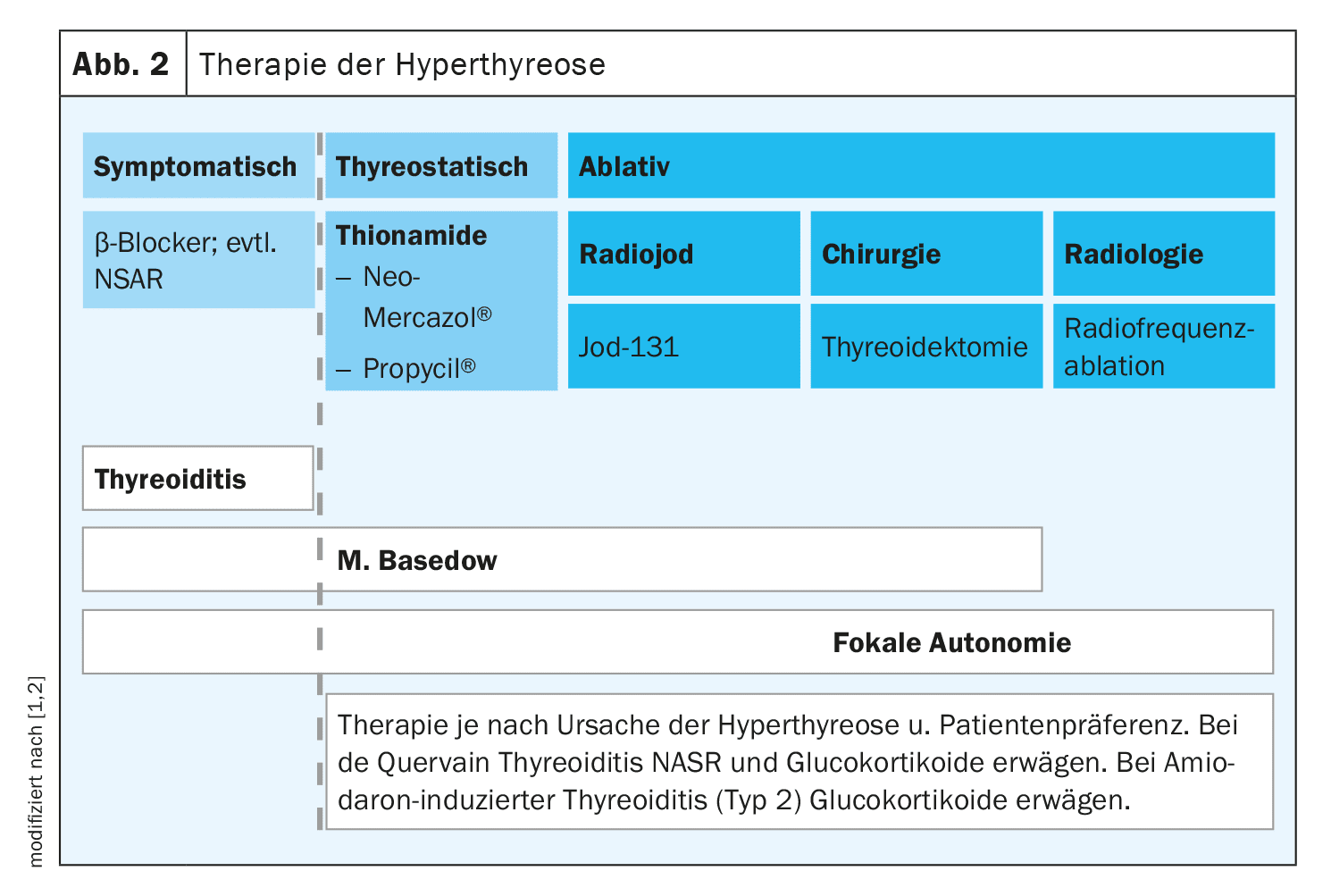

In the case of thyroiditis, medication is used to alleviate the symptoms of hyperthyroidism (e.g. beta blockers) or inhibit inflammation (NSAIDs, prednisone). Thyreostatics are not effective in thyroiditis, but are an important treatment option for Graves’ disease and thyroid autonomy. Thyreostatics inhibit the formation of thyroid hormones. The most commonly used are carbimazole (Neo-Mercazol®) or thiamazole [1,2]. In case of poor tolerance, propylthiouracil (Propycil®) can be used [1,2]. Alternatively, hyperthyroidism in the context of Graves’ disease or thyroid autonomy can be treated with radioiodine therapy or surgery (thyroidectomy).

A compact overview of the treatment options for thyroiditis, Graves’ disease and multifocal autonomy is shown in Figure 2.

Congress: FomF General Practitioner Training Days (Basel)

Literature:

- “Hormonal turbulence of the thyroid gland: from hypo- to hyperthyroidism”, PD Dr. med. Eleonora Seelig, FomF, GP training days, 05.-06.09.2024.

- Swissmedic: Medicinal product information, www.swissmedicinfo.ch,(last accessed 16.09.2024).

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2024; 19(10): 18-19 (published on 17.10.24, ahead of print)