One percent of all women are affected by premature ovarian failure. The exact cause is often unknown.

The term premature ovarian insufficiency (POI) refers to the premature loss of ovarian function before the age of 40 with the consecutive combined occurrence of hypergonadotropic hypogonadism and primary/secondary amenorrhea.

The prevalence of POI is thought to be 1% of the female population before 40 years of age or 0.1% before 30 years of age. Menopause between 40 and 44 years of age is called “early menopause/early menopause” and occurs with a prevalence of 5%. Menopause from 45 years of age is considered regular [1].

Diagnosis

POI is present when the following diagnostic criteria are met:

- Primary or secondary amenorrhea ≥4 months

- Age <40 years of life

- FSH ≥25 U/l, two measurements at an interval of >4 weeks.

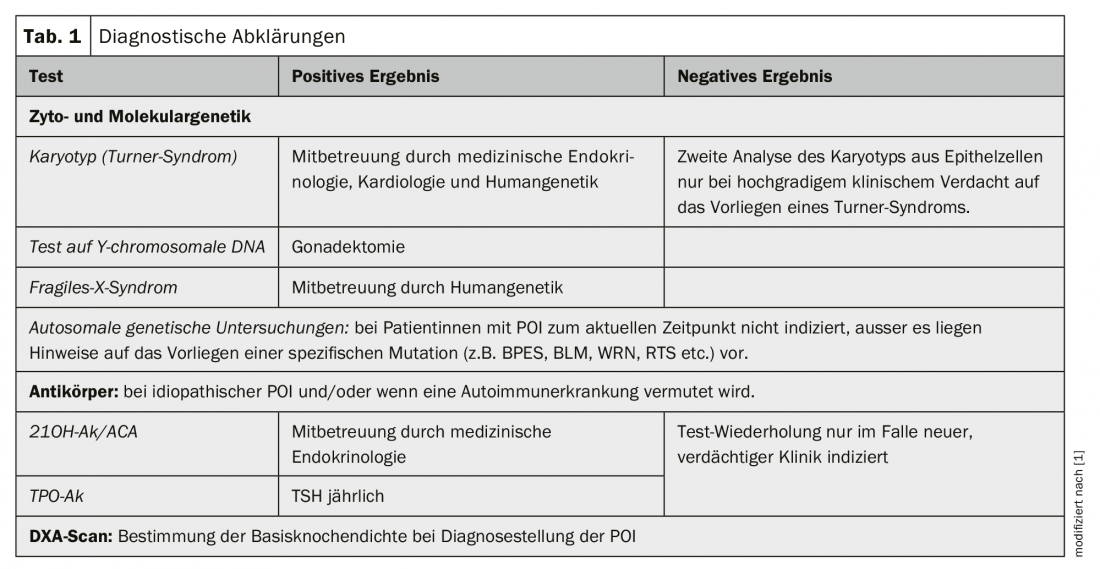

An overview of diagnostic clarifications is given in Table 1.

Etiology

Idiopathic POI: In the vast majority of all POIs (85-90%), no exact cause can be identified. This is then referred to as idiopathic POI [1].

Genetic POI: Chromosomal abnormalities are detectable in 10-13% of all patients with POI. The majority (94%) represent numerical and/or structural X chromosome aberrations (e.g. Turner syndrome) [1]. In cases of gonadal dysgenesis with detectable Y-linked DNA, prophylactic gonadectomy is recommended due to the significantly increased risk (45%) of developing a gonadal malignancy during progression [2]. Karyotyping should be performed in all women with non-iatrogenic POI [1].

Fragile X syndrome (Martin-Bell syndrome) is the most common cause of hereditary mental retardation. This X-linked dominant inherited disorder with decreased penetrance in the female sex is caused by a mutation in the FMR1 (“fragile-X-mental-retardation 1”) gene on the long arm of the X chromosome. In the presence of a premutation, females have a 13-26% risk of developing POI, but not so in the presence of the full mutation. In patients with sporadic POI, the prevalence of a FraX premutation is expected to be 0.8-7.5%, and as high as 13% in patients with a positive family history for POI [3]. Genetic exclusion of a FraX premutation is indicated in all patients with POI [1].

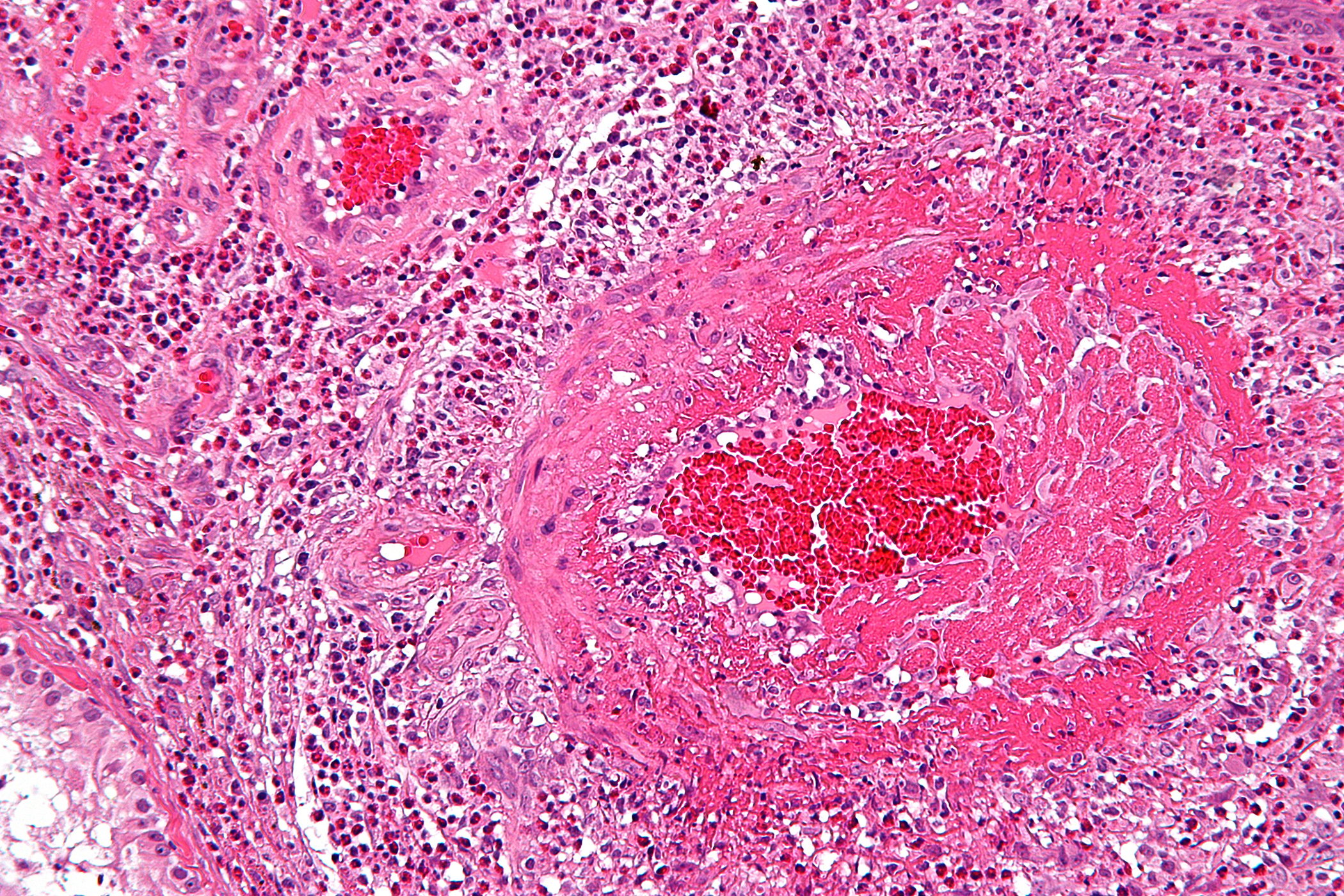

Autoimmunologically induced POI: In approximately 5% of all female patents with POI, the clinical picture is caused by autoimmunologically induced damage to the ovary. In the majority of autoimmune-related POIs, other organs besides the ovary are involved in the autoimmune process as part of a polyglandular autoimmune syndrome type 1/2. Here, autoimmunity directed against the adrenal cortex is found in 60-80% and against the thyroid gland in 14-27%. Ovarian biopsy for the diagnosis of POI due to autoimmunology is considered obsolete. The serological detection of so-called SCA (steroid cell antibodies) such as. 21OH-Ak (21-hydroxylase-Ak) or alternatively ACA/NNR-Ak (adrenocortical Ak/adrenocortical Ak), all of which are directed against enzymes involved in steroid hormone synthesis and thus potentially against the adrenal cortex, ovary, testes as well as the placenta, is the marker with the highest diagnostic sensitivity for an autoimmunologically caused POI. Consequently, screening for 21OH-Ak or alternatively ACA/NNR-Ak must be offered to all patients with idiopathic POI. In addition, screening for thyroid Ak (TPO-Ak) is indicated in all patients with idiopathic POI [1].

POI as a result of iatrogenic interventions (chemotherapy, radiotherapy, surgery): Cytotoxic chemotherapies have varying degrees of gonadotoxic effect depending on the agent used, the cumulative dose, and the age of the patient, which in turn is associated with an increased risk of developing POI.

Similarly, radiotherapy, depending on the dose of irradiation, the field of irradiation, and the age of the patient, impairs ovarian function to the point of POI.

Surgical interventions in the ovarian region, such as peeling out endometriomas in endometriosis, also lead to a significantly lower menopausal age as well as an increased risk of POI [4,5] due to the associated loss of healthy ovarian tissue with a consecutive reduction in ovarian reserve.

Short-term sequences of the POI

As with regular menopause, the intensity of estrogen-deficiency-related symptoms varies with POI. The spectrum ranges from completely asymptomatic patients who only present for clarification of amenorrhea to patients with considerable suffering. Typical menopausal symptoms include vasomotor complaints in the sense of hot flushes and outbreaks of sweating, sleep disturbances, physical and mental exhaustion, urogenital atrophy with complaints in the sense of an overactive bladder, stress incontinence, vaginal dryness with consecutive dyspareunia, recurrent urinary tract infections, sexual problems with libido deficiency and changes in sexual satisfaction, diffuse joint and muscle complaints, and depressed mood. Depending on the symptoms, systemic and, if necessary, additive local estrogen substitution is used therapeutically. However, even those POI patients who are asymptomatic require consistent systemic HRT to prevent the negative long-term effects of premature estrogen deficiency on cardiovascular health, bone metabolism, and cognitive function [6].

Long-term consequences of POI

Cardiovascular health: as a result of the premature cessation of the cardiovascular-protective estrogen effect, patients with POI have a significantly increased risk of cardiovascular disease as well as significantly increased cardiovascular mortality [7]. Starting substitution with sex steroids as early as possible and continuing it until the average regular menopausal age of 52 years is recommended to best counteract the increased cardiovascular risk [1].

Bone health: The beneficial influence of estrogens on the regulation of bone metabolism and the maintenance of bone structure, as well as the negative consequences of natural menopause on bone density and fracture risk are well known. POI has been shown to be associated with estrogen deficiency-related reduced bone density. This suggests that POI is consecutively associated with increased fracture risk, although this assumption cannot be adequately supported by studies at the current time [8]. When diagnosing POI, it is recommended to perform a DXA scan to determine the base bone density. In the case of age-appropriate normal bone density and initiation of adequately dosed HRT, repetition of the DXA scan is not necessary [1].

Estrogen replacement therapy is the treatment of choice for both prevention and treatment of osteoporosis in patients with POI. Consequently, initiation of HRT as early as possible and its continuation until the average physiological menopausal age is recommended [6].

Fertility, pregnancy and obstetric risks: HRT is not contraceptive and consequently can/must be recommended to all patients with an existing desire to have children. A sequential regimen is favored in positive childbearing. In contrast, patients for whom pregnancy is not an option require safe anticonception [1].

As a result of intermittent ovarian activity, especially initially, the chance of spontaneous pregnancy in POI cannot be completely ruled out, although it is very small. The chance of spontaneous conception naturally decreases with the duration of amenorrhea. A systematic review of fertility and pregnancy outcomes in POI found a spontaneous conception probability of 5-10%. 80% of these pregnancies resulted in live birth, and miscarriage occurred in 20% – numbers not different from normally fertile women [9].

At the current time, there are no known reproductive interventions that reliably improve ovarian activity and consequently spontaneous conception rates in POI. An ovarian response to stimulation with gonadodropins and/or ovulation induction is not expected due to the depleted oocyte reserve with consecutive already endogenously elevated gonadotropins. Consequently, once a diagnosis of POI has been made, the option of fertility protection has also passed. Oocyte donation is a realistic and well-established option for patients with POI to still become pregnant [1].

Neurological health: several large observational studies have found an increased risk of cognitive function decline or development of dementia in female patients with POI. The risk of cognitive impairment increased the younger the patient was at diagnosis. No mental impairment or increased risk of dementia was found in patients who had received estrogen replacement therapy by age 50 [10, 11]. Consequently, to reduce the risk of potential hormone deficiency-related cognitive impairment in patients with POI as much as possible, HRT should be given at least until the average regular menopausal age [1].

Sexual and urogenital function: adequate systemic estrogen replacement therapy provides the basis for normal sexual and urogenital function. If this is not sufficient, local estrogens can be used additively. Regarding optional additional androgen supplementation, long-term efficacy and safety data are lacking [1].

Quality of life: The diagnosis of POI has a significant negative impact on the psychological well-being and quality of life of the affected person. This must be addressed in discussions and psychological support offered.

Hormone replacement therapy

HRT for POI is indicated not only to alleviate estrogen deficiency-related symptoms, such as vasomotor symptoms, but also for prophylactic indications. At least standard-dose HRT should be recommended to patients with POI for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and for bone and neuroprotection until they reach the average physiologic menopausal age [1].

Active ingredient: On the one hand, classic HRT (estrogen: estradiol) and on the other hand combined oral contraceptives (estrogen: ethinyl estradiol) are used. Both synthetic progestins and the “bioidentical” micronized progesterone, each in transformation dose, can be used for endometrial protection.

Regimen: To avoid estrogen deficiency symptoms as much as possible, continuous estrogen replacement therapy is recommended. The vast majority of approved HRT preparations meet this requirement, but not the majority of approved hormonal anticonceptives. It is not uncommon for women with POI on combined oral anticonception in the 21/7 regimen to be symptomatic in the pill-free interval. Consequently, if anticonception is needed, prescription of pills in the 24/4 or 26/2 regimen or in the long cycle is advisable.

The question now arises as to whether the additive administration of progestins is better done continuously or cyclically. In principle, both HRT regimens can be used, depending on the patient’s preference. As a result of the frequently intermittent flare-up of ovarian activity, especially initially, unpredictable vaginal bleeding may occur repeatedly with a continuously combined regimen. Due to the regulated hormone withdrawal bleeding when using a sequential regimen, such a regimen is often preferred by patients, at least initially. Likewise in women of positive childbearing potential, since a sequential regimen best mimics the regular endometrial cycle with a cyclic alternation of proliferation and secretion phases. The desire for amenorrhea is met with the continuous combined regimen, which is superior to the sequential regimen in terms of endometrial safety [1].

Dosage form: data on HRT in timely menopausal women show that oral estrogens significantly increase the risk of VTE. Herein lies the advantage of transdermal estrogen therapy, which does not affect this risk [17]. The transdermal application of estradiol, in contrast to the per oral dosage form, can bypass the first-pass effect in the liver and consequently prevent the shift of the hemostaseological balance towards procoagulation. Although data on POI in this regard are lacking, transdermal administration of estrogens is preferable in patients at increased risk of VTE [1].

Breast cancer – the most feared risk: According to current data, patients with POI even have a significantly lower risk of breast cancer compared to the control group. This is most likely attributable to the premature sex steroid deficiency that inevitably accompanies POI. Women with POI should be reassured that, according to current data, HRT before reaching the regular/physiologic menopausal age does not increase the risk of breast cancer compared to the normal population. The fact that HRT, applied to patients after the age of 50, significantly increases the risk of breast cancer depending on the duration of therapy should not be extrapolated to patients with POI [1,6].

Take-Home Messages

- Premature ovarian failure requires a comprehensive diagnosis: history (chemotherapy, radiotherapy, surgery), clarification of genetic causes, exclusion of a polyglandular autoimmune syndrome.

- When a diagnosis is made, it is recommended that a DXA scan be performed to determine the basal bone density.

- Causal therapeutic approaches are lacking.

- Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) is indicated until the average regular menopausal age is reached to counteract the negative, estrogen-deficiency-related long-term effects of the condition on bone health, the cardiovascular system, and cognitive function.

Literature:

- European Society for Human Reproduction and Embyology (ESHRE) Guideline Group on POI, et al: ESHRE Guideline: management of women with premature ovarian insufficiency. Hum Reprod 2016; 31(5): 926-937.

- Michala L, et al: Swyer syndrome: presentation and outcomes. BJOG 2008; 115(6): 737-741.

- Wittenberger MD, et al: The FMR1 premutation and reproduction. Fertil Steril 2007; 87(3): 456-465.

- Raffi F, Metwally M, Amer S: The impact of excision of ovarian endometrioma on ovarian reserve: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012; 97(9): 3146-3154.

- Coccia ME, et al: Ovarian surgery for bilateral endometriomas influences age at menopause. Hum Reprod 2011; 26(11): 3000-3007.

- Hamoda H: British Menopause Society and Women’s Health Concern recommendations on the management of women with premature ovarian insufficiency. Post Reprod Health 2017; 23(1): 22-35.

- Roeters van Lennep JE, et al: Cardiovascular disease risk in women with premature ovarian insufficiency: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2016; 23(2): 178-186.

- Kanis JA, et al: A systematic review of intervention thresholds based on FRAX: A report prepared for the National Osteoporosis Guideline Group and the International Osteoporosis Foundation. Arch Osteoporos 2016; 11(1): 25.

- van Kasteren YM, Schoemaker J: Premature ovarian failure: a systematic review on therapeutic interventions to restore ovarian function and achieve pregnancy. Hum Reprod Update 1999; 5(5): 483-492.

- Rocca WA, et al: Increased risk of cognitive impairment or dementia in women who underwent oophorectomy before menopause. Neurology 2007; 69(11): 1074-1083.

- Phung TK, et al: Hysterectomy, oophorectomy and risk of dementia: a nationwide historical cohort study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2010; 30(1): 43-50.

- Langrish JP, et al: Cardiovascular effects of physiological and standard sex steroid replacement regimens in premature ovarian failure. Hypertension 2009; 53(5): 805-811.

- Crofton PM, et al: Physiological versus standard sex steroid replacement in young women with premature ovarian failure: effects on bone mass acquisition and turnover. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2010; 73(6): 707-714.

- Cartwright B, et al: Hormone Replacement Therapy Versus the Combined Oral Contraceptive Pill in Premature Ovarian Failure: A Randomized Controlled Trial of the Effects on Bone Mineral Density. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2016; 101(9): 3497-3505.

- Mueck AO: Postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy and cardiovascular disease: the value of transdermal estradiol and micronized progesterone. Climacteric 2012; 15(Suppl 1): 11-17.

- Davey DA: HRT: some unresolved clinical issues in breast cancer, endometrial cancer and premature ovarian insufficiency. Womens Health (Lond) 2013; 9(1): 59-67.

- Canonico M, et al: Hormone replacement therapy and risk of venous thromboembolism in postmenopausal women: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2008; 336(7655): 1227-1231.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2019; 14(5): 9-12