Current and historical concepts on the origin of migraine, pain triggers and how to combat them. Latest potentially groundbreaking development in the prophylactic field: the CGRP antibodies.

Up to 15-20% of the population reacts with a migraine in certain situations. Women are three times more likely to be affected. With regard to the pathophysiology and causes of migraine, it is now known that there is a genetic predisposition. Second, the central role of the trigeminovascular pain system in the head is discussed. Evidence exists (though data are still scarce) that differences exist between the pain system in the head and that in the rest of the body – e.g., medication overuse back pain is poorly understood compared to headache (FMD) and it is questionable whether such a form even exists.

Of course, developments in the therapeutic field are always pathophysiologically exciting and relevant. While triptans (serotonin receptor agonists), drugs that act on the serotonin mechanism, were actually discovered to be effective in migraine by chance, the neuropeptide CGRP (calcitonin gene-related peptide), which is currently under therapeutic investigation, has been known since the early 1990s to play an important role as a metabolite in the process of pain processing [1]. After many years of animal and human research, a therapy concept has now been developed that is currently being tested in clinical trials – with success, as it turns out [2]. The role of CGRP in migraine development has not yet been finally clarified – especially with regard to the migraine phases – but if it is induced, a migraine can be triggered; if it is blocked, a migraine can be treated. Thus, it is the first truly targeted treatment approach that intervenes in pathophysiology.

The fact that serotonin also plays a crucial role (among other things as a messenger of pain processing) is shown by the fact that other drugs that act on serotonin, such as serotonin/norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) or even the older tricyclics can be prophylactically effective in migraine.

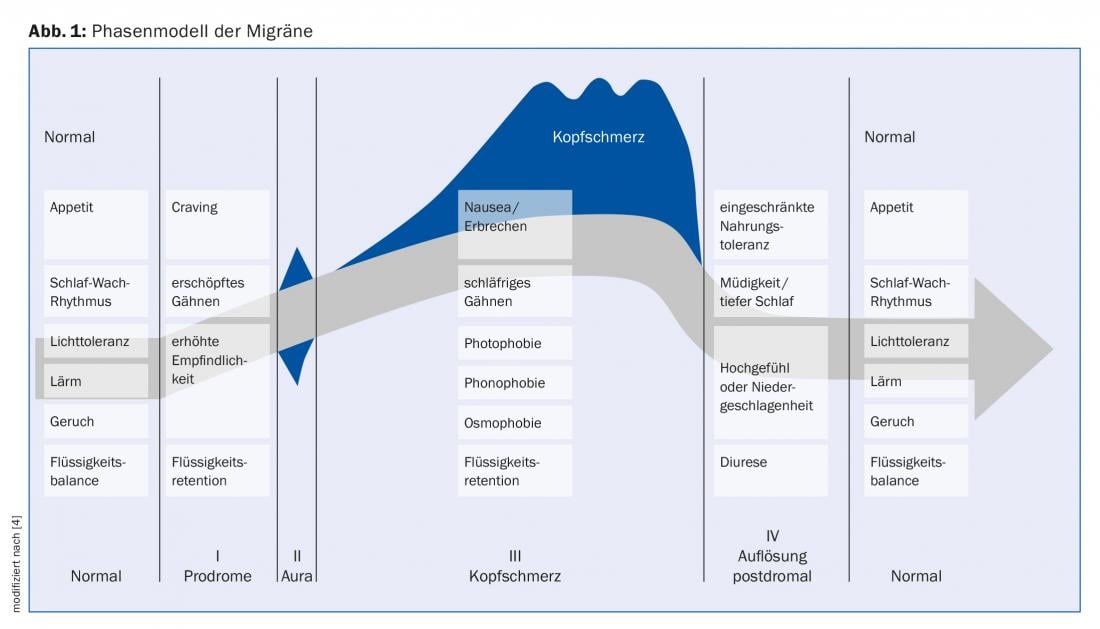

Phase model of migraine

Currently, research is generally interested not only in the pain phase (between 4 and 72 hours), but increasingly in the antedromal (up to two days in advance) [3] and postdromal phases (again, up to two days) (Fig. 1) [4]. The first drugs targeting CGRP were direct CGRP antagonists in acute therapy and prophylaxis [5]. However, these led to side effects (transaminase increase) when used frequently, which is why the studies had to be discontinued. Today, the CGRP pathway is being investigated therapeutically mainly in the form of the monoclonal antibodies and only in prophylaxis (four companies are currently maintaining corresponding phase II and III trials, approval is pending). Between attacks, recent research shows that the brain of migraine patients runs in a kind of “overdrive” mode [6], i.e., more energy is used than in a normal brain and fewer reserves are available. You can compare it figuratively with a “Porsche with a small tank”; breakdowns are inevitable here if you don’t constantly refill the gasoline. This knowledge is now also incorporated into the administration of the dietary supplements magnesium, riboflavin or vitamin B2 and coenzyme Q10.

Migraine patients also have a so-called habit deficit, i.e. they become less accustomed to stimuli. For example, when exposed to flashes of light, migraine brains respond the same way over and over again, much like children’s brains, whereas brains without this pathology eventually get used to it and shut down. The habit deficit increases over time and then falls back to normal with the migraine attack until the cycle begins again. A recently published study using daily functional imaging for one month was able to demonstrate this cycle [7].

“Vascular” theory

In the past, the so-called “vascular theory” was often discussed with regard to pathophysiology, which saw migraine headaches as being mainly due to dilatation of the blood vessels. This had also explained the effect of triptans, which make vasoconstriction. Nowadays, this thesis has largely been abandoned. The effect of triptans is much more due to the aforementioned receptor agonism.

Trigger factors

Triggers are basically very individual. In women who have a predisposition to migraine, hormonal changes or the menstrual cycle are a very decisive factor. During the reproductive phase, when hormones are at play, migraines are common. This is mainly attributed to estrogen deprivation. There are cases when migraine starts in puberty and ends with menopause.

Another reliable trigger is alcohol, even in small amounts. There are currently no clear studies on the influence of weather conditions (“weather sensitivity”), but patients frequently report a connection. Stress can trigger migraine in two ways: some suffer from headaches during the stressful phase, others afterwards in relaxation mode (so-called “managerial/weekend migraine”).

An overview of the triggers mentioned can be found in reference [8].

Food products are also discussed again and again, e.g. products containing histamine. However, these give a diffuse tension headache rather than a migraine headache. However, eating regularly, i.e. at fixed times, can help against migraine. The same applies to sleep (as “regular” a lifestyle as possible). To date, there is no clear evidence on individual specific foods such as the frequently mentioned cheese, citrus fruits or chocolate.

Tension is also frequently reported, which could be due in no small part to the fact that nearly 60% of the population report neck pain. They may simply be perceived more strongly at the beginning of the migraine because the pain threshold is lowered. Then you feel the pain first in the neck, but since it is also there between attacks – ultimately always – it does not make sense to assume this as a trigger.

Migraine, as we have seen before, is a cyclical disease. So if a trigger is added in a phase just before the next attack, the attack may occur earlier. But even without triggers, the attack would have come at some point, i.e., the triggers interact to have a reinforcing effect, not a triggering effect.

In analogy to anxiety disorder or allergology, first indications are also collected in migraine whether a kind of “desensitization” or at least coping with the triggers can be achieved instead of avoiding them completely (“coping” instead of “avoidance”) [9].

Therapy Update

Following the above, one can therapeutically try, for example, to prolong the phases before the breakdown by providing energy to the brain, or the “overdrive” is slowed down or attenuated, e.g., with a beta blocker or an antiepileptic drug.

Basically, migraine therapy can be divided into three pillars: Non-drug measures as well as pharmacological acute therapy and prophylaxis.

For non-drug measures, a regular lifestyle with physical activity is recommended. There is also very good evidence for relaxation techniques such as progressive muscle relaxation (PMR), autogenic training, etc. Effects are of course not to be expected overnight, but rather through discipline and patience. There are also good studies on acupuncture, including a Cochrane review that confirms a positive effect [10]. Complementary medicine definitely has its place in migraine therapy.

In acute care, nonvasoconstrictor approaches are currently being explored for use in patients with vascular risk factors. The 5-HT1F receptor agonist lasmiditan (not yet approved) should be mentioned here. Otherwise, there are the old familiar triptans. In Germany, the active ingredients are already available “over the counter” (OTC).

Therapy with stimulators is new, for which the evidence is also improving. One of these devices is, for example, Cefaly®, which is placed frontally on the forehead or occipitally [11]. It is a so-called TENS device (“transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation”). Vagus stimulation with e.g. gammaCore® is also possible. However, there is more data on this so far in cluster headache. Transcranial magnetic stimulation is mainly used in England. It could be used especially in migraine with aura. The advantage is that the devices have very few side effects (up to -free) and are self-controllable.

Prophylactically, monoclonal antibodies against CGRP are now the focus of interest. These are injections that have shown convincing results (in endpoints such as monthly migraine days) with a good side effect profile in various phase II and III trials compared to placebo [12–15]. Of course, it is not yet possible to make a more precise statement about long-term safety. However, common typical side effects such as fatigue, dizziness, weight gain are hardly found here. What exactly happens in the body when the CGRP system is blocked, however, is not yet known. Compared with triptans, which are formally contraindicated in vascular disease, the new drugs do not have a vasoconstrictor mechanism. It is also interesting that in the studies mentioned there was an astonishingly large rate of people who had a complete response, i.e. no migraine at all. We do not know this to this extent from other studies, at most from therapy with botulinum toxin (not approved in Switzerland for this indication). The agents are primarily being studied in episodic, but also chronic migraine (≥15 days) and also cluster headache.

Take-Home Messages

- Various approaches are now being investigated in the pathophysiology and etiology of migraine: genes play a central role.

- The trigeminovascular pain system in the head is primarily involved in the development of pain. The findings on CGRP, a neuropeptide involved in the process of pain processing, are already being used therapeutically.

- In general, research is currently interested not only in the pain phase, but increasingly also in the prodromal and postdromal phases.

- Trigger factors are individual and range from cycle-related hormonal fluctuations to irregular lifestyle in the

- areas of nutrition and sleep to alcohol and stress.

- Therapeutically, the monoclonal antibodies against CGRP are currently the main focus of interest. They show convincing results in prophylaxis with good safety and without vasoconstrictive properties.

Constitution in collaboration with Red. (ag)

Literature:

- Goadsby PJ, Edvinsson L, Ekman R: Release of vasoactive peptides in the extracerebral circulation of humans and the cat during activation of the trigeminovascular system. Ann Neurol 1988 Feb; 23(2): 193-196.

- Ho TW, Edvinsson L, Goadsby PJ: CGRP and its receptors provide new insights into migraine pathophysiology. Nat Rev Neurol 2010 Oct; 6(10): 573-582.

- Giffin NJ, et al: Premonitory symptoms in migraine: an electronic diary study. Neurology 2003 Mar 25; 60(6): 935-940.

- Blau JN: Migraine: theories of pathogenesis. Lancet 1992 May 16; 339(8803): 1202-1207.

- Ho TW, et al: Randomized controlled trial of the CGRP receptor antagonist telcagepant for migraine prevention. Neurology. 2014 Sep 9; 83(11): 958-966.

- Gantenbein AR, et al: Sensory information processing may be neuroenergetically more demanding in migraine patients. Neuroreport 2013 Mar 6; 24(4): 202-205.

- Schulte LH, May A: The migraine generator revisited: continuous scanning of the migraine cycle over 30 days and three spontaneous attacks. Brain 2016 Jul; 139(Pt 7): 1987-1993.

- Kelman L: The triggers or precipitants of the acute migraine attack. Cephalalgia 2007 May; 27(5): 394-402.

- Martin PR: Managing headache triggers: think ‘coping’ not ‘avoidance’. Cephalalgia 2010 May; 30(5): 634-637.

- Linde K, et al: Acupuncture for the prevention of episodic migraine. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016 Jun 28; (6): CD001218.

- Schoenen J, et al: Migraine prevention with a supraorbital transcutaneous stimulator: a randomized controlled trial. Neurology 2013 Feb 19; 80(8): 697-704.

- Sun H, et al: Safety and efficacy of AMG 334 for prevention of episodic migraine: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Neurol 2016; 15: 382-390.

- Bigal ME, et al: Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of TEV-48125 for preventive treatment of high-frequency episodic migraine: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2b study. Lancet Neurol 2015; 14: 1081-1890.

- Dodick D, et al: Safety and efficacy of ALD403, an antibody to calcitonin gene-related peptide, for the prevention of frequent episodic migraine: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, exploratory phase 2 trial. Lancet Neurology 2014; 13: 1100-1107.

- Dodick D, et al: Safety and efficacy of LY2951742, a monoclonal antibody to calcitonin gene-related peptide, for the prevention of migraine: a phase 2, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Lancet Neurology 2014; 13: 885-892

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2017; 12(3): 12-15