Cystic fibrosis is an autosomal recessive genetic disorder in which a defect in the CFTR gene causes disease. The defective chloride channel causes the disease to manifest in different organs. However, the main life-limiting manifestation remains the lungs. Accordingly, this is also where most emergencies or complications occur.

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is an autosomal recessive genetic disorder in which a defect in the CFTR genecauses disease. The defective chloride channel causes the disease to manifest in different organs. However, the main life-limiting manifestation remains the lungs. Accordingly, this is also where most emergencies or complications occur. After the lungs, the gastrointestinal tract is most commonly involved in emergencies. The emergencies usually occur in adulthood, but are not uncommon in childhood or adolescence. Hardly any other disease causes such a large number of complications and emergencies as cystic fibrosis [1].

Emergencies after organ manifestation: lung – pneumothorax

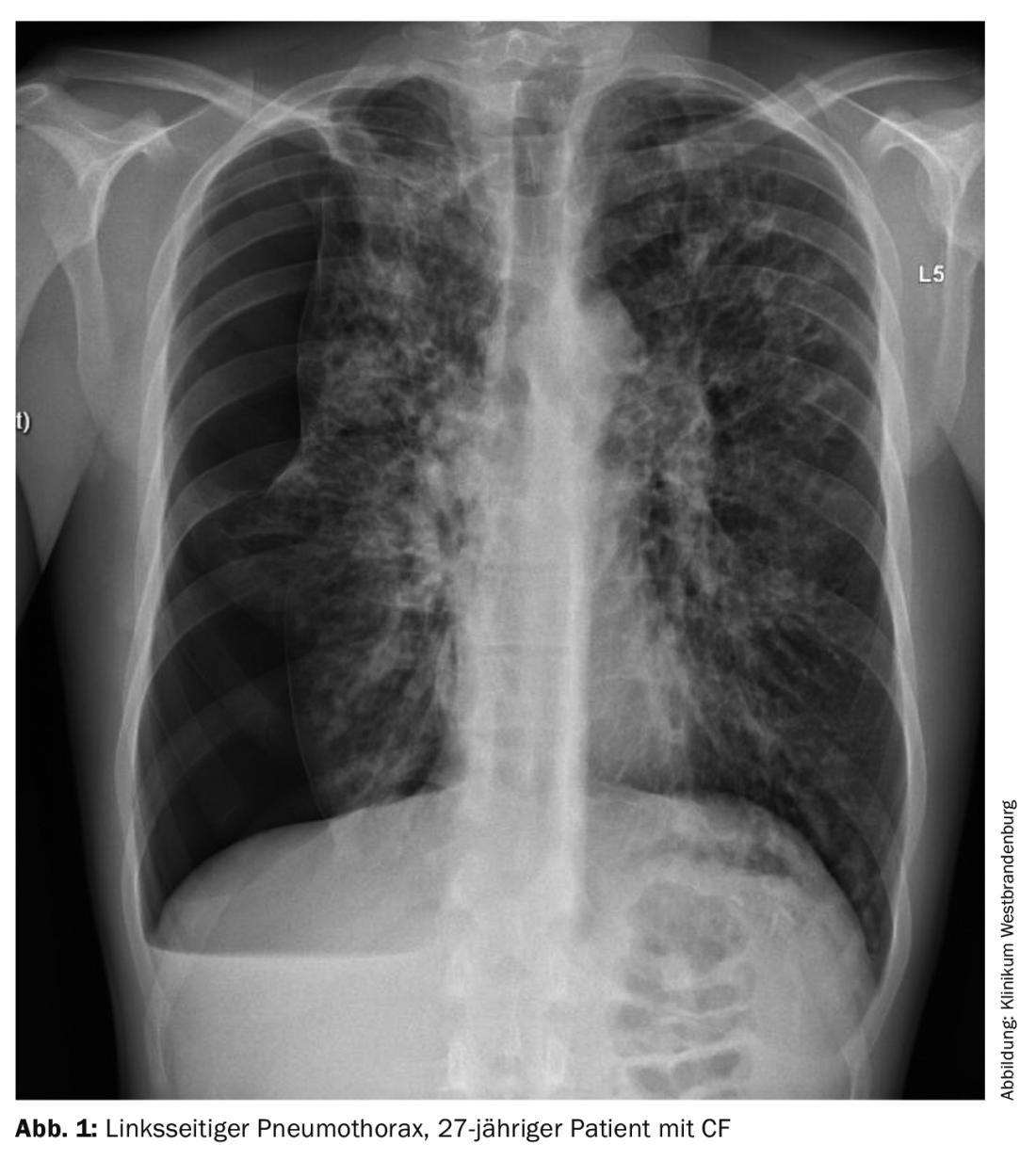

First and foremost in the pulmonary manifestation of CF is pneumothorax as an emergency, which occurs especially in adults (Fig. 1) . The symptoms cannot always be clearly separated from those of a pulmonary exacerbation. In addition to sudden dyspnea, chest pain and hemoptysis are the most common symptoms that must be considered in this differential diagnosis. Immediate medical action is indicated for pneumothorax, especially tension pneumothorax with mediastinal shift. The indication for placement of an intrapleural burethral drain is then immediate.

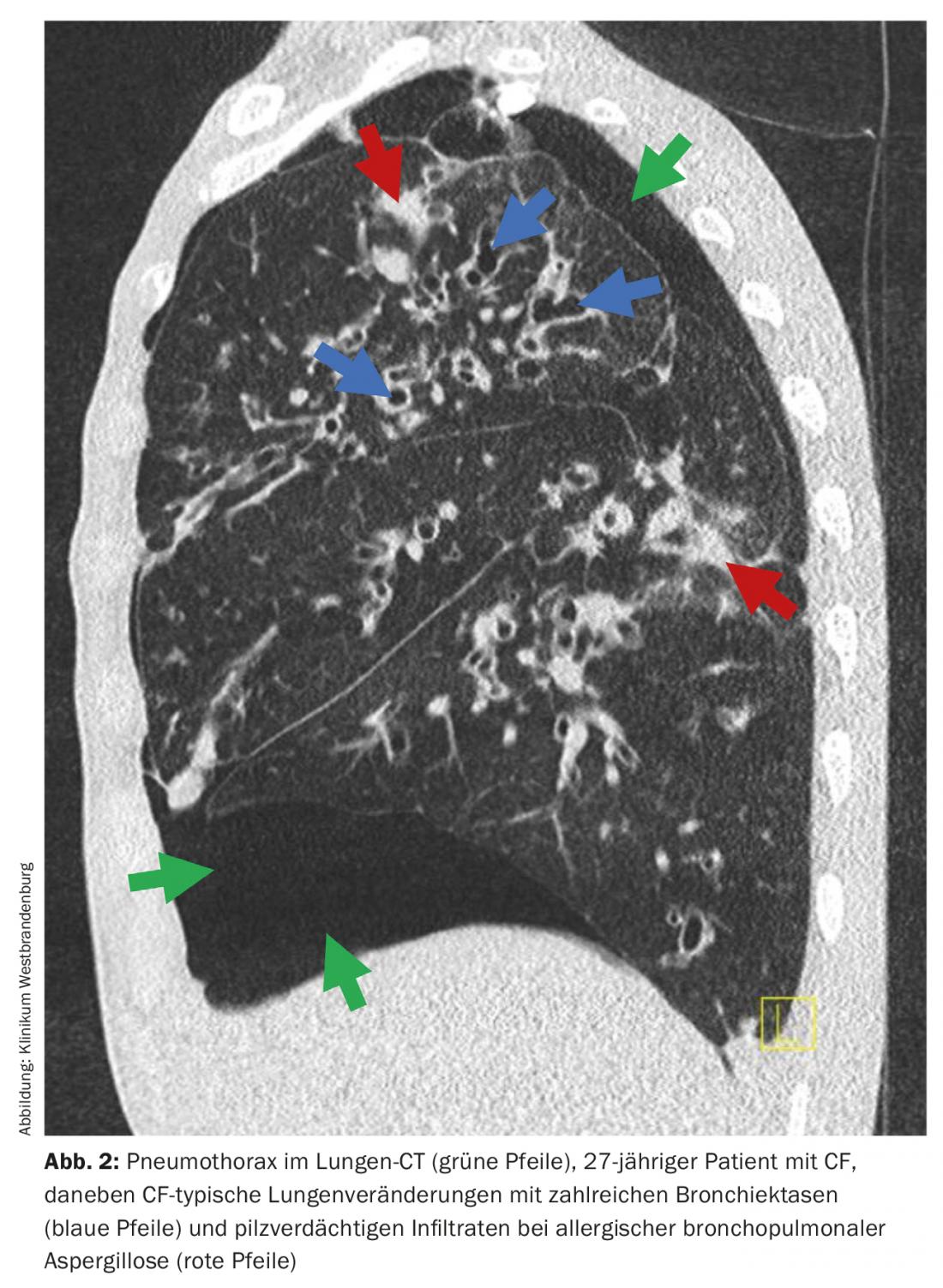

In CF, there is a particular risk for pneumothorax complications because large fistulas are often present, with an associated risk for pleural empyema. The reason for this is that patients almost always have a permanent colonization or infection with bacteria – it is not uncommon for these to be multi-resistant germs, such as a 4 MRGN Pseudomonas aeruginosa. For this reason, antibiotic therapy should also be given initially based on the results of the microbiological findings of the last sputum [2]. Surgical intervention is rarely required, but in cases of pleural adhesions, thoracoscopically guided drainage insertion under direct vision may be an alternative in addition to CT-guided chest drainage insertion (Fig. 2) [2]. In advanced lung disease, the topic of lung transplantation should also always be addressed in the case of pneumothorax, as pneumothorax can negatively affect the clinical course and thus significantly influence the prognosis.

Lung – acute hemoptysis/hemoptysis

Another emergency – due to the almost always present bronchiectasis in people with CF – can be hemoptysis or hemoptysis. In this situation, severity is differentiated based on the amount that is coughed up. Severe hemoptysis in which the patient coughs up >250 ml of fresh bloody secretions is an emergency, so rapid intervention may be necessary. Close cooperation with interventional radiologists has become established, who are then called in to perform embolization of the bleeding pulmonary artery. In the case of smaller amounts of blood, hemostasis with medication (for example, tranexamic acid) can be attempted first. Since a bronchopulmonary infection exacerbation is usually causative for the bleeding, antibiotic therapy should be started immediately and given concomitantly. In addition, clotted blood also represents another risk factor for bronchopulmonary infection, again providing argumentative support for antibiotic administration [2].

Lung – acute pulmonary artery embolism

Another pulmonary emergency is pulmonary artery embolism, which may also be clustered in patients with CF. Causes are, as in other patients, deep vein thrombosis, but also implanted port catheter systems for antibiotic administration [2]. Treatment of pulmonary artery embolism follows current guidelines, even in patients with CF [3]. In individual cases, however, increased hemoptysis is to be expected due to blood thinning, which is why the therapy must then be adjusted.

Lung – acute respiratory failure

Furthermore, respiratory failure is common in CF and advanced lung disease. This poses a particular challenge to practitioners, as intubation combined with invasive ventilation and the associated immobilization is a major risk in patients with cystic fibrosis. For this reason, attempts are always made to bypass intubation. Since this is done in cooperation with the intensive care physicians, it is essential for CF centers treating critically ill patients to cooperate with an experienced intensive care unit in order to allow the patient to continue breathing and coughing on his own without tracheal intubation, if possible. To make this a medical reality, in such emergencies, patients with cystic fibrosis can be connected to an extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) procedure. In this context, awake ECMO is primarily advocated to keep the patient mobile and to further enable independent expectoration of secretions. This is usually more effective than flexible bronchoscopy.

However, in principle, the goal is that patients with CF do not need to be placed on ECMO, but rather evaluated early for lung transplantation and placed on the active waiting list for double lung transplantation without ECMO [2].

Gastrointestinal tract – acute distal intestinal obstruction syndrome.

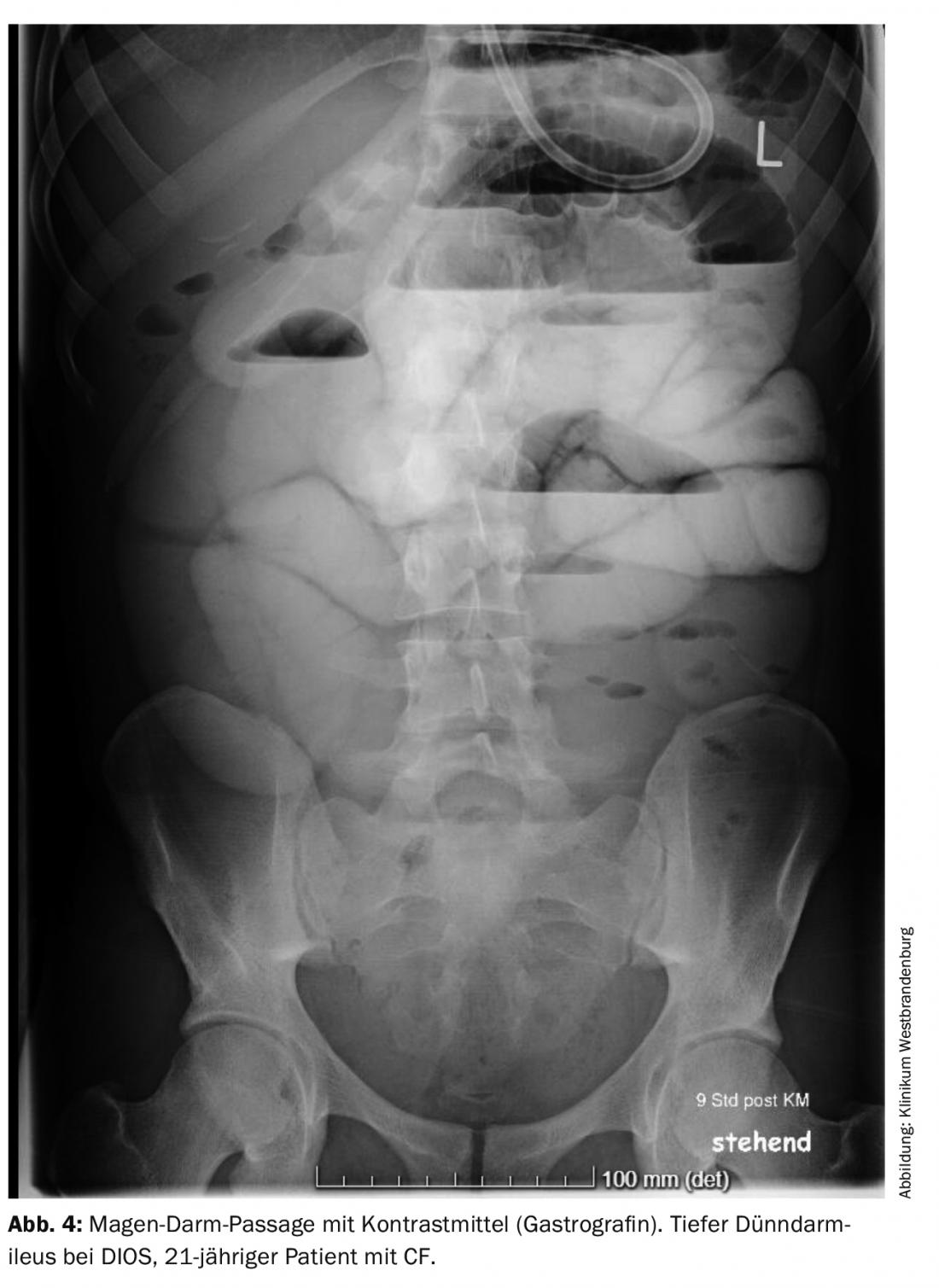

In addition to the lungs, complications of CF occur primarily in the liver or gastrointestinal tract. The most common abdominal emergency is the so-called DIOS (distal intestinal obstruction syndrome) (Fig. 3). In particular, pancreatic insufficiency and uncontrolled steatorrhea as well as dehydration are considered to be of etiologic importance. In most cases, the first event occurs after 18 years of age and rarely before 5 years of age [4]. In addition, a clustering with increasing patient age, as well as with severe mutation classes and poor pulmonary situation can be observed. After a DIOS, recurrent disease then occurs in up to 50% of patients [4]. Importantly, surgical abdominal disease may be precipitating or may occur subsequently, e.g., appendicitis, intestinal adhesions after surgery, ileocolic intussusception, and volvulus. These conditions should be actively sought when clinical evidence is present. In DIOS, small bowel obstruction classically occurs just anterior to Bauhin’s valve. Clinically, this emergency presents as an ileus (Fig. 4) . However, it does not require surgical treatment if conservative therapy is initiated in time. The combination of laxative oral and colorectal measures in combination with intestinal peri-stal-tic activating stimulants has proven effective in this regard. In addition, fluid substitution is an important component of DIOS therapy [5].

Gastrointestinal tract – acute esophageal variceal bleeding

Another dreaded emergency is esophageal variceal hemorrhage. It usually occurs in association with the frequent hepatic manifestations of mucovsicidosis (ca. 35,3%, Tab. 1), as a result of cirrhosis of the liver and thus also the formation of esophageal varices. For this reason, close cooperation with gastroenterologists and especially with hepatologists plays an important role in the care of patients with CF. Regular esophagogastroduodenoscopy is the standard of care in patients with cirrhosis and CF to evaluate esophageal varices and their extent (Fig. 5) . This can identify early indications for ligation of the varices and possibly prevent bleeding. All-cause mortality does not appear to be significantly affected by esophageal bleeding [6].

Gastrointestinal tract – acute hepatic failure, pancreatitis and cholecystitis.

Acute liver failure is not prominent in adulthood, but may be a very rare emergency indication in childhood with an indication for rapid liver transplantation.

Many patients with CF are affected by exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, i.e. a dysfunction in the formation and secretion of pancreatic digestive enzymes. Pancreatitis is less common and only affects CF patients who do not have pancreatic insufficiency. Most patients are initially treated as inpatients at the CF center, but recurrent pancreatitis and mild forms can sometimes be treated as outpatients [5].

Due to the defective CFTR channel in the bile duct epithelium, pathological changes also occur in the bile ducts. The primary concern here is decreased biliary bicarbonate production. In addition to a so-called microgall bladder, cholecystolithiasis and cholecystitis in particular are increasingly described in CF [7]. The associated biliary colic, which is usually acute, is not usually a life-threatening emergency but usually requires inpatient treatment. In rare, often recurrent cases, cholecystectomy should be performed.

Kidney – acute nephrolithiasis

Increased excretion of oxalic acid through the intestine, which is a consequence of the impaired digestive function of the intestine in cystic fibrosis due to the defective chloride channel, can lead to nephrolithiais (oxalate stones) [8]. Without intervention, the stones are often also excreted in the urine without complications; however, they can also become lodged in the draining urinary tract and lead to renal colic. However, in nephrolithiasis, the mucous membranes of the urinary tract may be injured and, accordingly, bleeding may occur. In consultative discourse with the urologists, decisions are made about possible interventions (splinting of the ureter using a catheter, endoscopic removal of the stone, lithotripsy, etc.).

Kidney – acute renal failure

In patients with CF, renal insufficiency may occur mainly due to the use of drugs such as NSAID or intravenous antibiotics, especially aminoglycosides commonly used in CF. Chronic renal failure progresses rather slowly and is asymptomatic for a long time. In contrast, severe symptoms and a life-threatening situation develop very quickly in acute renal failure. Acute renal failure is an absolute emergency.

Skeleton – bone fractures in osteoporosis

Osteoporosis is present in approximately 7% of adult CF patients (Table 1). Rib fractures may occur due to severe coughing and the pressure on the chest. Normally, no special therapy needs to be performed. However, if there is a rib fracture that – in very rare cases – injures the lung, surgical treatment of the pulmonary trauma and possibly the rib fracture must be performed. In addition, due to the pain from the rib fracture, there is often a buildup of secretions in the lungs because adequate expectoration is not possible. Then, it is imperative to provide appropriate pain management and even consider antibiotic therapy to prevent bronchopulmonary exacerbation.

Emergencies due to medication administration

Regardless of organ manifestations, emergencies in patients with CF also occur in the context of therapy, as mentioned earlier in renal failure. Because of the frequent pulmonary infections, mainly caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa but also by other multidrug-resistant germs, these complications are related to the antibiotic therapies. In addition to the very common antibiotic intolerances, which can progress to anaphylactic shock and acute hemolysis, acute renal failure and antibiotic-associated pseudomembranous colitis can also occur, which then require rapid hospitalization [1].

Hypotonic dehydration/salt depletion syndrome

Due to the defective chloride channel, dehydration occurs more rapidly in patients with CF. The body therefore excretes too much salt, especially during exertion and at high ambient temperatures or fever, but also during diarrhea and vomiting (pseudo-Bartter syndrome). Salt loss is particularly problematic in infants and young children and it can lead to life-threatening situations, but older children and adults can also enter medically relevant hypotonic dehydration if fluid and NaCl substitution is too low. This is an important differential diagnosis, especially in warm summer months, when the clinical condition of a patient with CF worsens.

Hyper- and hypoglycemias

The so-called CFRD or diabetes mellitus type 3 in CF is to be distinguished from the other types. Approximately one third of adult patients with CF develop CFRD [1,9] (Table 1). The pancreas usually still has a residual endocrine function, so that significantly more blood glucose fluctuations can occur than in other diabetics. Patients with diabetes mellitus in CF (CFRD: CF-Related Diabetes) may experience hypo- or hyperglycemia. Severe hypoglycemia may also occur spontaneously in CF without exogenous insulin administration, rarely even in patients without manifest diabetes. However, ketoacidosis almost never occurs in patients with CF, and therefore acute hyperglycemic events requiring intervention almost never occur [9].

Summary

Due to the significantly improved prognosis of cystic fibrosis, patients are now living much longer, but complications and emergencies are correspondingly increasing with age. Thus, internal medicine challenges are becoming more frequent and complex. In addition to great expertise, this requires above all good cooperation with other specialist disciplines besides pneumology. Among all complications and emergencies, pulmonary complications and emergencies have a special significance in patients with CF. They may signal the need for review or indication for lung transplantation in patients with significantly impaired lung function. This should always be discussed with a transplant center at an early stage to determine possible processes with regard to transfer or else necessary diagnostics for possible listing for transplantation. Since gastroenterological complications are frequent and important in addition to pulmonary emergencies, there should be close clinical cooperation with gastroenterology and the CF center. In addition to medical know-how, patient education regarding potential emergencies and complications is extremely important for their successful diagnosis and treatment.

Take-Home Messages

- Emergencies in CF are common in adult patients.

- Emergencies should be cared for in a specialized CF center.

- SOPs for the most important and common emergencies should be established in every CF center.

Note: Emergency passport and emergency brochure at the German Cystic Fibrosis Association.

www.muko.info

Support in Switzerland:

https://cystischefibroseschweiz.ch

Literature:

- Schwarz C, Staab D: Cystic Fibrosis and associated complications. Internist 2015 Mar; 56(3): 263-274; doi: 10.1007/s00108-014-3646-z.

- Garcia B, Flume PA: Pulmonary Complications of Cystic Fibrosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2019 Dec; 40(6): 804-809; doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1697639. Epub 2019 Oct 28.

- Rali PM, Criner GJ: Submassive pulmonary embolism. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2018 Sep 1; 198(5): 588-598; doi: 10.1164/rccm.201711-2302CI.

- Green J, Carroll W, Gilchrist FJ: Interventions for treating distal intestinal obstruction syndrome (DIOS) in cystic fibrosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018 Aug 3; 8(8): CD012798; doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012798.pub2.

- Regard L, Martin C, Chassagnon G, Burgel PR: Acute and chronic non-pulmonary complications in adults with cystic fibrosis. Expert Rev Respir Med 2019 Jan; 13(1): 23-38; doi: 10.1080/17476348.2019.1552832. epub 2018 Nov 30.

- Ye W, Narkewicz MR, Leung DH, et al: Variceal Hemorrhage and Adverse Liver Outcomes in Patients With CysticFibrosis Cirrhosis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2018 Jan; 66(1): 122-127; doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001728.

- Assis DN, Debray D: Gallbladder and bile duct disease in cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros 2017 Nov; 16 Suppl 2: S62-S69; doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2017.07.006.

- Hoppe B, von Unruh GE, Blank G, et al: Absorptive hyperoxaluria leads to an increased risk for urolithiasis or nephrocalcinosis in cystic fibrosis. Am J Kidney Dis 2005 Sep; 46(3): 440-445; doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.06.003.

- Ode KL, Chan CL, Granados A, et al: Cystic fibrosis-related diabetes: medical management. J Cyst Fibros 2019 Oct; 18 Suppl 2: S10-S18; doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2019.08.003. PMID: 31679720.

- Nährlich L (ed.), Burkhart M, Wosniok J et al: German Cystic Fibrosis Registry – Report Volume 2019; https://www.muko.info/fileadmin/user_upload/angebote/qualitaetsmanagement/register/berichtsbaende/berichtsband_2019.pdf (retrieved: Nov 12, 2021).

InFo PNEUMOLOGY & ALLERGOLOGY 2022; 4(1): 6-10.