Pruritus is a common problem in the elderly, which can occur not only in the context of dermatoses, but also as a secondary symptom of other diseases. Aging skin is characterized by characteristic changes in the individual skin layers. Among other things, lipid production and hydration decrease. There is a wide range of treatment options for dermatologic pruritus, although there are several things to consider in this patient population.

According to the current guideline or IFSI (“International Forum for the Study of Itch”) classification, the following possible causes of chronic pruritus are distinguished: Dermatological diseases, systemic diseases, neurological disorders, psychological/psychosomatic symptoms, and multifactorial or unclear genesis [1]. If it is suspected that the pruritus is a secondary symptom of non-dermatologic diseases, in addition to obtaining a medication history, detailed information on the medical history should be obtained and patients should be evaluated for the presence of underlying causative diseases (e.g., renal and hepatic function tests) and, if necessary, receive appropriate therapy.

Drug treatment spectrum for dermatologically caused pruritus

If the pruritus is dermatologically caused, the use of active ingredients with proven anti-pruritic efficacy is useful in addition to adequate basic care [2].

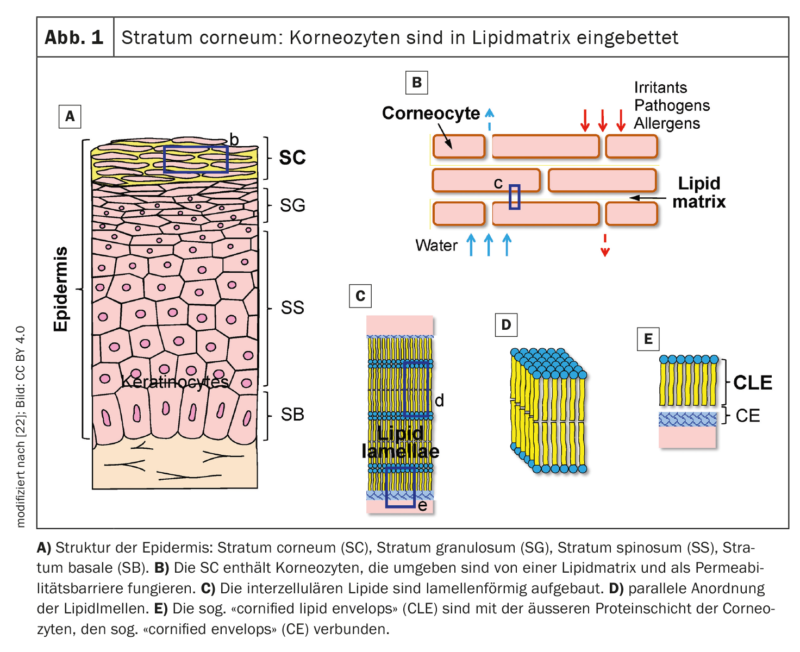

Emollients and gentle cleansers: all patients suffering from localized pruritus and xerosis should initially be suggested emollients as first-line treatment [2]. Moisturizers containing a mixture of physiological skin lipids similar to those naturally occurring in the skin (ceramides, cholesterol, fatty acids, etc.) are used to hydrate the stratum corneum (Fig. 1) , as well as restore barrier function and relieve itch symptoms [2]. Suitable emollients may contain as additives substances that exhibit anti-pruriginous properties, including, for example, urea, polidocanol, menthol, or palmitoylethanolamide [3]. It should be noted that fragrances and preservatives may cause allergic contact dermatitis in certain patients; therefore, a “repeat open application test” (ROAT) is advised before regular use. The authors point out that the regenerative capacity of skin barrier function to irritants such as surfactants or alkaline soap is slowed in the elderly. Therefore, skin cleansing products containing mild surfactants are advisable. Xerotic eczema tends to worsen with frequent and prolonged exposure to high air temperatures, such as sauna visits.

Topical corticosteroids and topical calcineurin inhibitors: Topical corticosteroids (TCS) achieve antipruritic effects through their anti-inflammatory action. Since no direct itch control is effected, efficacy is largely limited to pruritus in the setting of inflammatory dermatoses [2]. Long-term use of highly potent TCS may result in weakened skin barrier function and telengiectasia, as well as senile purpura [4].

Topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCIs) are primarily used for inflammatory skin conditions such as atopic dermatitis and seborrheic dermatitis. In addition to the anti-inflammatory effect, TCI are thought to relieve itch by activating TRPV (transient receptor potential) channels 1 in peripheral C nerve fibers, with subsequent desensitization [2,4]. Itching usually improves within 48h after the first application. With continued treatment, a further reduction in pruritus can be expected. Initially, the sensation of burning skin may occur as a result of TRPV1 activation, but this generally disappears after several applications. For long-term use, TCIs are preferable to TCSs because skin atrophy does not occur [2,4].

H1 antihistamines: Oral H1 antihistamines block the H1 receptor of afferent C nerve fibers and, in sufficiently high doses, can also inhibit the release of mast cell mediators [5]. Because antihistamines are relatively safe and economical, they are often used in patients with pruritus, but randomized clinical trials of efficacy in pruritus have been limited to urticaria [4,6]. Because first-generation antihistamines readily cross the blood-brain barrier, they can be sedating and lead to anticholinergic side effects, which can be particularly unpleasant for the elderly [7]. These anticholinergic side effects include dry mouth, diplopia, visual field defects, and micturition difficulties. Furthermore, hydroxyzine is very lipophilic and has a longer half-life in elderly patients. The Beers Criteria of The American Ger iatrics Society advises caution in the use of antihistamines in this patient population due to the aforementioned side effects as well as an increased risk of delirium and Alzheimer’s disease [8,9]. With the newer second-generation antihistamines (e.g., fexofenadine, cetirizine, levocetirizine, loratadine, rupatadine, and ebastine), the risk for setative effects or anticholinergic side effects is lower, and the interaction potential is also comparatively small [23].

Biologics: Dupilumab is a fully humanized monoclonal antibody that blocks interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-13 and has been shown to reduce pruritus in patients with atopic dermatitis [10]. In addition, dupilumab has been shown to have an itch-reducing effect in other dermatoses such as nummular eczema, contact dermatitis, and prurigo nodularis [11–13].

Another biologic that rapidly reduced pruritus significantly in studies is the monoclonal antibody nemolizumab directed against IL-31 [2,11]. And the recombinant humanized monoclonal IgG antibody omalizumab (binds to free IgE and inhibits mast cell function) is recommended in European guidelines for the treatment of chronic urticaria when sufferers do not respond to antihistamines or ciclosporin. It is noted that itch/urticaria symptoms often recur around 4-10 weeks after discontinuation of omalizumab [14]. Another strategy for itch blockade involves the use of neurokinin-1 receptor (NK-1R) antagonists such as aprepitant or tradipitant. These prevent binding of the natural ligand for NK-1, substance P, to the NK-1 receptor. Substance P has been shown to play an essential role in itch development [15,16]. Aprepitant has so far been officially approved in Switzerland for the treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea [24].

| Features of the skin in older age Xerotis cutis is a common cause of pruritus in the elderly, with prevalence ranging from 38-85% [19]. Age-correlated changes in the barrier function of the stratum corneum (SC), as well as proteases, ph environment, and decreased activity of sebaceous and sweat-secreting glands are associated with dry skin and chronic pruritus [20,21]. There are changes in the composition of epidermal lipids as well as increased transepidermal water loss (TEWL). The stratum corneum provides a barrier to reduce TEWL and provide protection from external factors and is subject to constant cellular turnover. With age, desquamation processes may change, contributing to the appearance typical of dry skin [2]. An increased tendency to hyperkeratosis, erythema, and episodes of pruritus can be explained by impairments in cutaneous barrier function. |

Small Molecules: Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors are available in oral and, more recently, topical forms. Topically applicable agents that have shown promising results in clinical trials for pruritus include the phosphodiesterase (PDE)-4 inhibitor crisaborol and the JAK inhibitors delgocitinib and ruxolitinib [17,18]. Some of the cytokine targets of JAK inhibitors such as IL-4, IL-13, IL-31, and IL-17 have been implicated in the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis. To date, the oral JAK inhibitors baricitinib, upadacitinib, and abrocitinib have been approved for this indication [24]. Apremilast (PDE4 inhibitor) has been shown to relieve pruritus in patients with psoriasis [14].

Immunomodulators: ciclosporin and azathioprine have been shown to be effective in the treatment of various inflammatory skin conditions [14]. The possible side effects of ciclosporin include hypertension, infections, and elevation of creatinine levels and nephrotoxicity [2]. Azathioprine can cause nausea, vomiting, anemia, and hypersensitivity reactions such as dizziness, diarrhea, fatigue, and skin rashes [2]. Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), whose immunosuppressive effects are due in part to a blockade of lymphocyte proliferation, exhibits less toxicity than ciclosporin [2]. Among other things, MMF has proven effective in the treatment of chronic urticaria and eczema. Dapsone has evidence of efficacy for chronic urticaria and angioedema, but side effect risks include anemia, skin rashes, peripheral neuropathy, gastrointestinal side effects, and hepatotoxicity.

Literature:

- Ständer S, et al.: S2k Leitlinie: Diagnostik und Therapie des chronischen Pruritus. JDDG 2022; 20(10): 1386–1402.

- Chung BY, et al.: Pathophysiology and Treatment of Pruritus in Elderly. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Dec 26; 22(1): 174.

- Ständer S, et al.: S2k-Leitlinie zur Diagnostik und Therapie des chronischen Pruritus. Kurzversion. JDDG 2017;15:860–873. doi: 10.1111/ddg.13304g.

- Papier A, Strowd LC: Atopic dermatitis: A review of topical nonsteroid therapy. Drugs Context 2018; 7: 212521.

- Metz M, Ständer S: Chronic pruritus—Pathogenesis, clinical aspects and treatment. JEADV 2010; 24: 1249–1260.

- Matsuda KM, et al.: Gabapentin and pregabalin for the treatment of chronic pruritus. JAAD 2016; 75: 619–625.e6.

- Adelsberg BR: Sedation and performance issues in the treatment of allergic conditions. Arch Intern Med 1997; 157: 494–500.

- Endo JO, et al.: Geriatric dermatology: Part I. Geriatric pharmacology for the dermatologist. JAAD 2013; 68: 521.e1–521.e10.

- Gray SL, et al.: Cumulative use of strong anticholinergics and incident dementia: A prospective cohort study. JAMA Intern Med 2015; 175: 401–407.

- Gooderham MJ, et al.: Dupilumab: A review of its use in the treatment of atopic dermatitis. JAAD 2018; 78: S28–S36.

- Ruzicka T, et al.: Anti-Interleukin-31 Receptor A Antibody for Atopic Dermatitis. NEJM 2017; 376: 826–835

- Guttman-Yassky E, et al.: Baricitinib in adult patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: A phase 2 parallel, double-blinded, randomized placebo-controlled multiple-dose study. JAAD 2019; 80:913–921.e9.

- Guttman-Yassky E, et al.: Upadacitinib in adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: 16-week results from a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. JACI 2020; 145 :877–884

- Leslie TA, Greaves MW, Yosipovitch G: Current topical and systemic therapies for itch. Handb Ex Pharmacol 2015; 226: 337–356.

- Schmidt T, et al.: BP180- and BP230-specific IgG autoantibodies in pruritic disorders of the elderly: A preclinical stage of bullous pemphigoid? BJD 2014; 171: 212–219.

- Choi H, et al.: (2018) Manifestation of atopic dermatitis-like skin in TNCB-induced NC/Nga mice is ameliorated by topical treatment of substance P, possibly through blockade of allergic inflammation. Exp Dermatol 27(4): 396–402.

- Nakagawa H, et al.: Delgocitinib ointment, a topical Janus kinase inhibitor, in adult patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: A phase 3, randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled study and an open-label, long-term extension study. JAAD 2020; 82: 823–831.

- Yosipovitch G, et al.: Early Relief of Pruritus in Atopic Dermatitis with Crisaborole Ointment, A Non-steroidal, Phosphodiesterase 4 Inhibitor. Acta Derm Venereol 2018; 98: 484–489.

- White-Chu EF, Reddy M: Dry skin in the elderly: Complexities of a common problem. Clin Dermatol 2011; 29: 37–42.

- Valdes-Rodriguez R, Stull C, Yosipovitch G: Chronic Pruritus in the Elderly: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis and Management. Drugs Aging 2015;32:201–215.

- Yosipovitch G, et al.: Skin Barrier Damage and Itch: Review of Mechanisms, Topical Management and Future Directions. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2019;99:1201–1209.

- «The Pathogenic and Therapeutic Implications of Ceramide Abnormalities in Atopic Dermatitis», by Masanori Fujii; Cells 2021; 10(9): 2386; www.mdpi.com/2073-4409/10/9/2386, (letzter Abruf 26.05.2023)

- Hon KL, et al.: Chronic Urticaria: An Overview of Treatment and Recent Patents. Recent Pat. Inflamm. Allergy Drug Discov 2019; 13: 27–37.

- Arzneimittelinformation, www.swissmedicinfo.ch, (letzter Abruf 26.05.2023)

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2023; 33(3): 34–35