Urticarial lesions on more than three days per week and persisting for more than six weeks define chronic urticaria. Angioedema may be concomitant (40%) or the only symptom (<10%). Chronic urticaria is divided into a spontaneous and an inducible form. Because nonspecific factors can trigger an attack, chronic urticaria is often confused with allergy. Chronic spontaneous urticaria usually resolves spontaneously, in about 50% of cases within one year. For localized lesions >24 hours, a biopsy search for a vasculitic inflammatory component is recommended. A broad laboratory workup is not recommended, but a search for systemic signs of inflammation is useful. Autologous serum skin test (ASST) and basophil activation test (CU-BAT) can be used to delineate autoreactive forms of urticaria, which is primarily prognostic in nature. Treatment follows a stepwise regimen and is primarily symptom-oriented (H1 antihistamines, if necessary in the high-dose range, omalizumab [Xolair®] or the off-label use of leukotriene antagonists or cyclosporin A in therapy-refractory cases). No long-term therapy with corticosteroids (only in relapse).

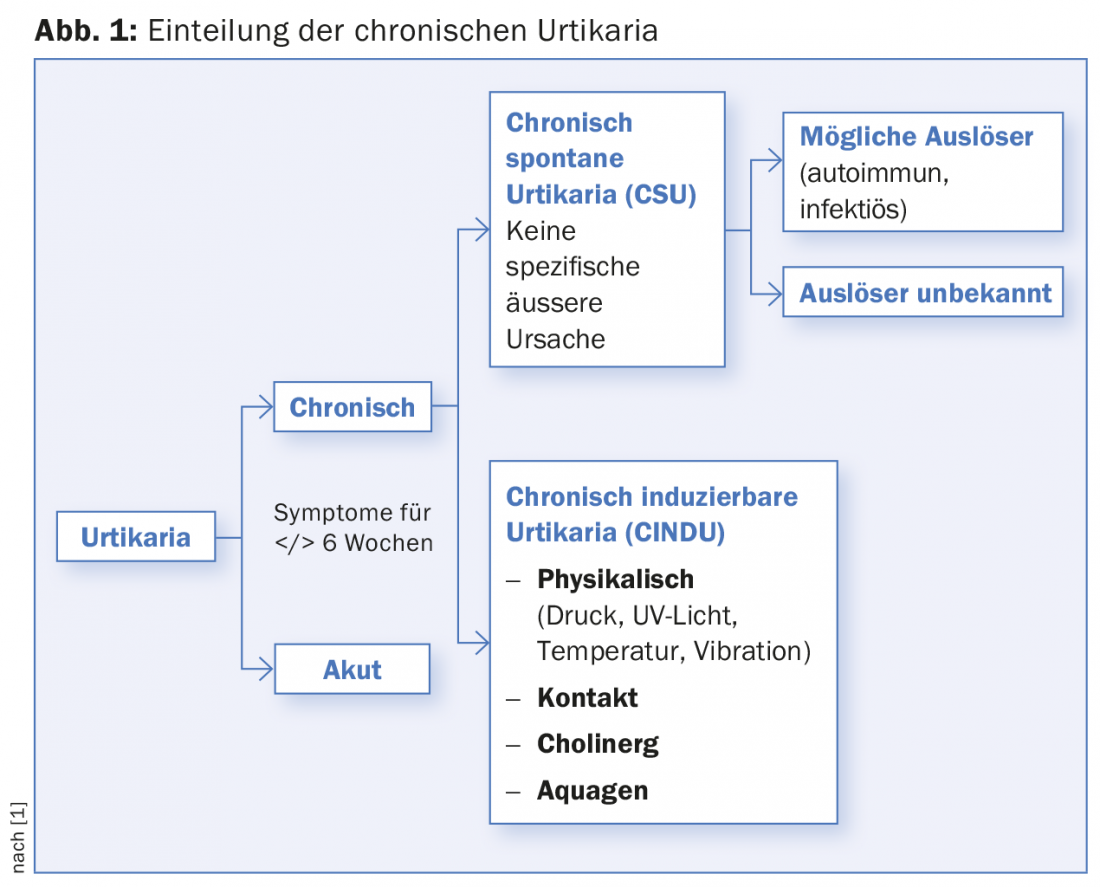

Urticaria is a common skin condition and is divided into acute and chronic forms based on duration (</> 6 weeks), with the latter requiring at least three weekly occurrences. For acute urticaria, it is not uncommon to find a specific, sometimes allergic cause. On the other hand, chronic forms represent a real challenge, first and foremost chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU), which we will focus on here. CSU accounts for two-thirds of chronic urticaria, with inducible forms accounting for the remaining third (Fig. 1). With a point prevalence of about 0.5-1%, CSU is also not uncommon in general medical practice, with women being affected about twice as often as men and showing a maximum in middle age [1–4]. In most cases, no trigger for CSU can be found, the course is unpredictable, and the quality of life of the affected person is significantly limited, which is stressful for both the treating physician and the patient. The clinical course is very variable, so that disease courses of a few months up to 40 years can occur. The average duration of the disease is between three and five years [5].

Contrary to popular belief, CSU is a classic non-allergic disease [6,7]. However, like all immediate-type allergic reactions, it is based on the activation of mast cells (and also basophils), which, after degranulation and release of various mediators, especially histamine, result in the formation of wheals and angioedema.

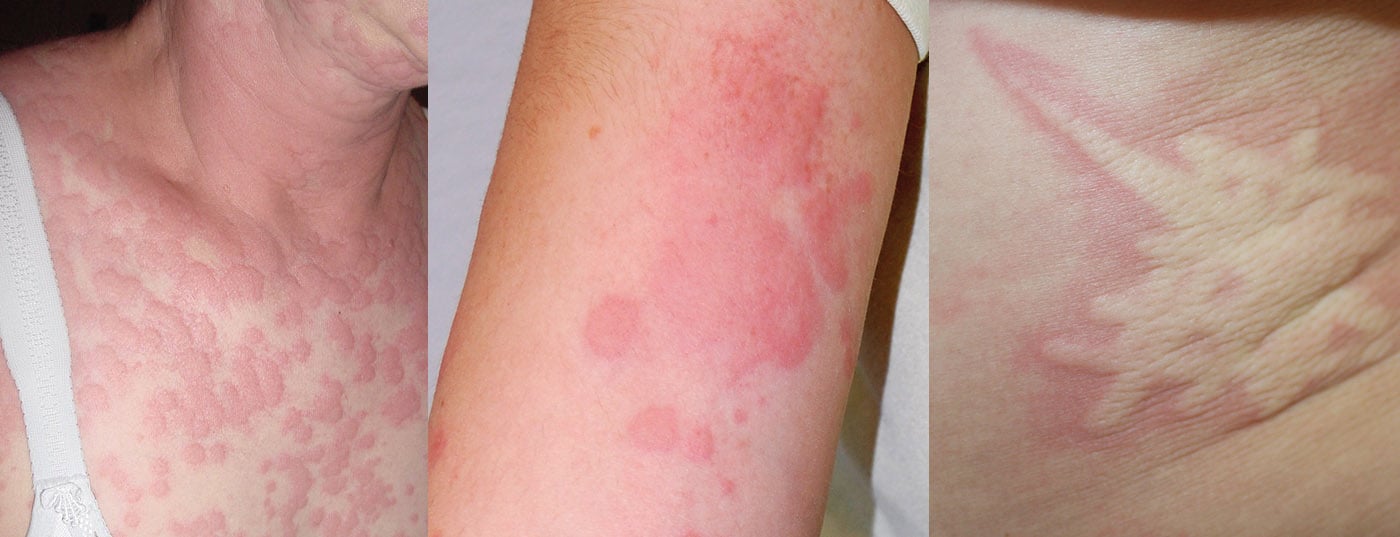

The polymorphous, intensely pruritic urticae, which not infrequently confluence to form extensive lesions, can occur on all parts of the body, but especially on the extremities, trunk, and pressure-exposed areas (Fig. 2). Concomitant angioedema occurs in approximately 40%, typically on the face, hands, and genital area. Rarely, angioedema without concomitant urticarial skin lesions may be the only CSU manifestation (<10%). However, they must be distinguished as histamine-related from the even rarer hereditary forms of angioedema [8]. Urticarial lesions that persist at the same site for more than 24 hours are suspicious for an inflammatory event, e.g., urticarial vasculitis syndrome with possible involvement of internal organs, and should be biopsied and examined histologically (including native preparation for immune complex complement analysis). Marking the boundary with a ballpoint pen can be helpful here in the assessment.

Pathogenesis

The central effector cell of all forms of urticaria is the mast cell. The histamine released by it after degranulation, together with other mediators, leads to a cutaneous reaction occurring within a few minutes with vasodilation, increase in vascular permeability and stimulation of sensory nerves. Other factors attract other inflammatory cells (e.g. basophils, neutrophils, etc.), which are involved in the formation of wheals.

Activation of mast cells in CSU can occur via numerous pathways, not all of which are known in detail. Autoimmune or autoreactive mechanisms are found in 40-60% of those suffering from CSU [9]. Autoantibodies of the IgG/IgM isotype against IgE itself or against the high-affinity Fc IgE receptor (FceRI) could be detected [10]. Mast cell degranulation here is triggered by autoantibody-induced cross-linking of Fc-IgE receptors. At the same time, the autoantibodies can activate the complement system, which leads, among other things, to the formation of complement factor C5a, which can also stimulate mast cells and basophils in an IgE-independent manner.

In addition to autoantibodies, other low-molecular-weight serum components are capable of activating the mast cell system, details of which are not yet known. In addition to factors of the complement system, a connection with coagulation components, among others, is suspected. Fittingly, some patients with CSU show elevated thrombin levels, which likely result from activation of the intrinsic coagulation pathway (via factor XII) [11].

Diagnosis

A detailed history and clinical examination are the most important tools to diagnose CSU [12]. In particular, the testing of physical triggers (dermographism, temperature, pressure, vibration) plays an important role here, and for study purposes, sometimes very sophisticated standardized test procedures have been developed [13]. In practice, however, pens, ice cubes and a weight-bearing belt are sufficient (Fig. 3) . Questions about medications taken (e.g. painkillers, ACE inhibitors), long-distance travel and a targeted system history are also included. It is important here to note intermittent fever, muscle/joint pain, malaise, and weight loss as clinical signs of an underlying systemic inflammatory disease, such as vasculitis or collagenosis. In 80-90% of cases, however, no cause can be found either anamnestically or clinically, which is why CSU was formerly called chronic idiopathic urticaria [7].

Although, as mentioned above, it is not an allergy, certain factors have an influence on the course of the disease. Many foods (especially those with colorings and preservatives) can increase a CSU. These contain biogenic amines, which can have a histamine-like effect. Similar to food, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and some other drugs such as opiods or X-ray contrast media can also lead to an urticarial episode in already ill patients via direct and IgE-independent mast cell stimulation. This is often confused with a drug allergy because of the temporal relationship. Similarly, physical stimuli such as pressure, solar radiation, or temperature also influence the expression of wheals and angioedema in CSU. The above cofactors vary from case to case and should be discussed with the patient.

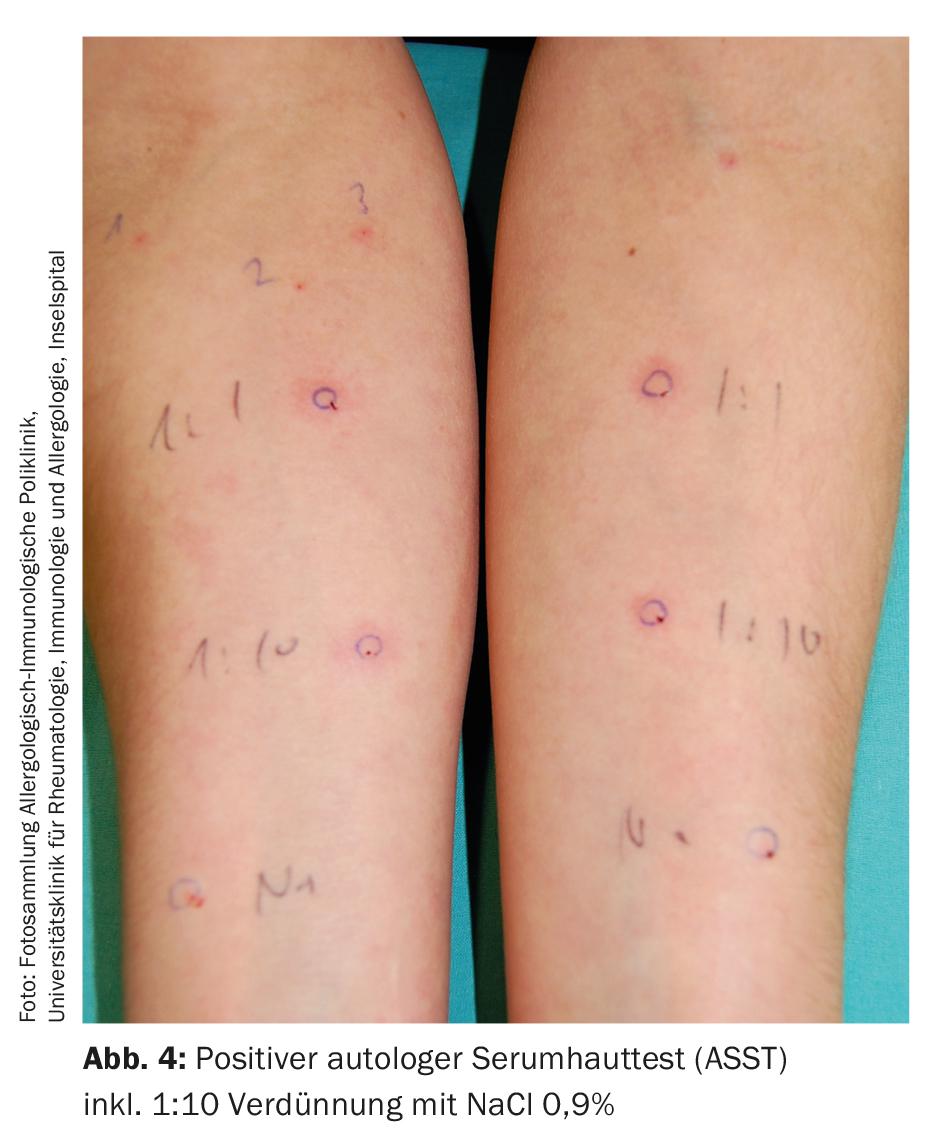

Several studies have already shown that comprehensive laboratory tests do not provide further insights in the vast majority of cases and are therefore not recommended [12]. However, it is important to note that some autoimmune diseases are clustered in patients with chronic urticaria. Besides thyreopathies, these are mainly rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren’s syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, celiac disease, type 1 diabetes mellitus, and probably several others [3]. Some laboratory parameters are therefore quite useful to delineate systemic diseases. This includes determination of blood count, BSR/CRP, thyroid function, and serum protein electrophoresis. In addition, basal serum tryptase control can be used to detect the presence of mast cell disease (mastocytosis), which can rarely be the cause of CSU. In addition, autologous serum skin testing (ASST, Fig. 4) is performed at specialized centers, which provides indirect evidence of autoreactive serum components [10].

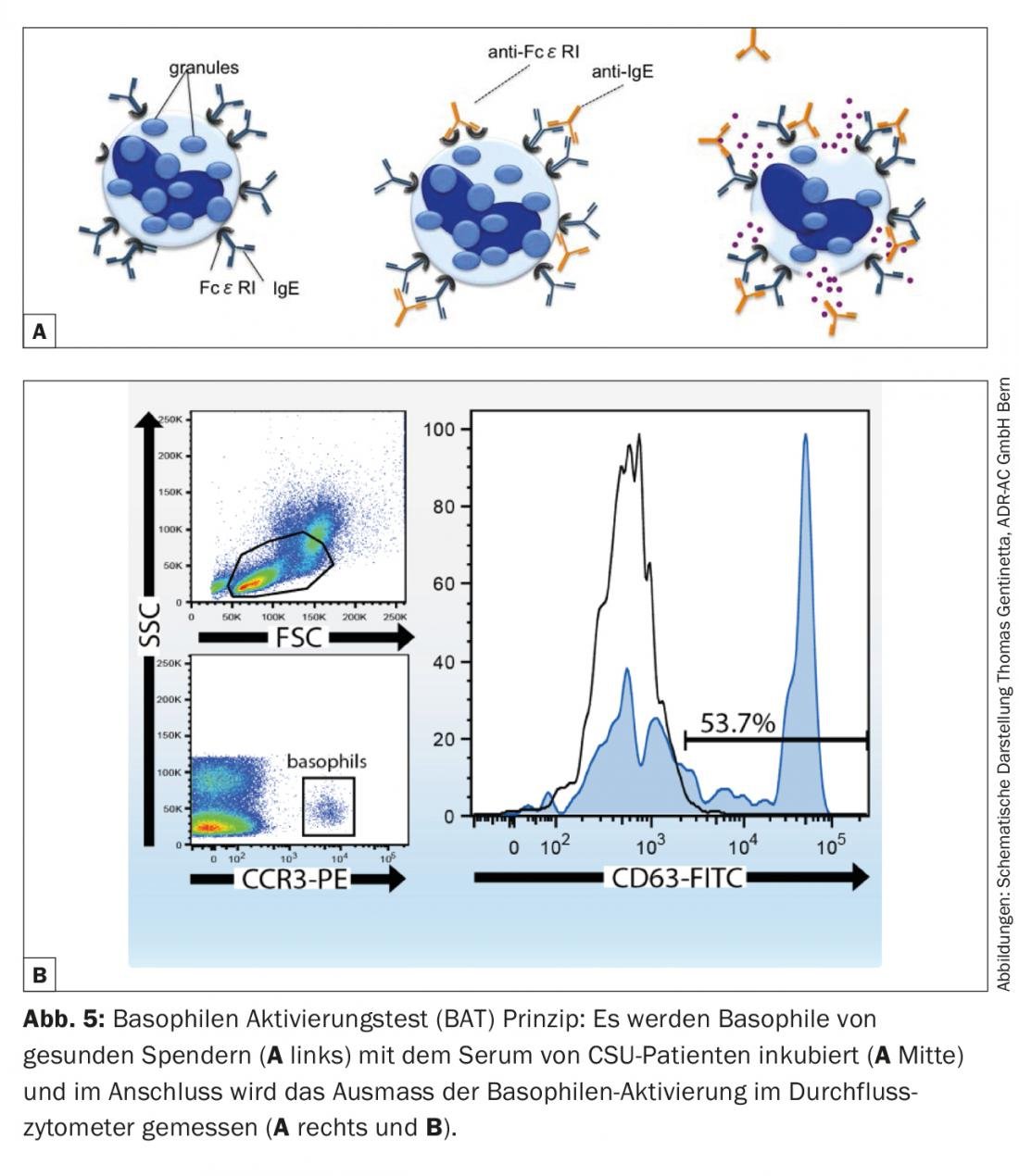

However, since this requires discontinuation of the basic therapy with antihistamines for several days and there is a residual risk of iatrogenic infection if the injected serum is mixed up, a safe and reliable in vitro alternative has been established in recent years in the form of the basophil activation test (CU-BAT). This involves incubating well-characterized basophils from healthy donors with serum from CSU patients [14]. By measuring defined activation markers on the basophil surface (CD63, CD203c) by flow cytometry, it can be determined whether the serum of the diseased person contains factors that can activate basophils (and consequently also mast cells with a comparable receptor repertoire on the surface) (Fig. 5). Both tests (ASST, CU-BAT) have a primarily prognostic character. Autoreactive forms of urticaria usually have longer courses and are more difficult to treat, which is also true for CSU patients with marked accompanying angioedema [12]. A positive test may therefore influence treatment, since immunomodulatory medication such as cyclosporine A or the anti-IgE antibody omalizumab (Xolair®) can be resorted to more rapidly if the patient is expected to be refractory to therapy. Last but not least, finding an autoreactive genesis also has a psychological significance for the affected person, which may increase acceptance of the diagnosis and adherence to treatment.

Therapy

At the beginning of treatment, there should certainly be good education about the disease, optimally with the distribution of written material (e.g., the information brochure “Urticaria” of the Allergy Center Switzerland, www.aha.ch). Because patients with chronic urticaria are often confused, they should be informed that despite the chronic course, the disease rarely persists and resolves within one year in approximately 50% of cases [7]. However, prolonged persistence and recurrence of urticaria after several years despite treatment are possible. It is also important to note that despite the often severe symptoms, which noticeably reduce the quality of life, it is only in exceptional cases a dangerous disease.

If cofactors play a role, avoiding these triggers as much as possible is a good measure. Patients who have noticed a connection with certain foods and are positive about a diet can certainly benefit here [15], whereby the urticaria usually only decreases in intensity, but hardly disappears. Similarly, the above painkillers (NSAIDs, opioids in higher dosage) should be avoided. In contrast, paracetamol or selective COX-2 inhibitors (etoricoxib, celecoxib) are usually well tolerated. Wearing loose-fitting clothing, consistent use of sunscreen, and avoiding heat buildup or severe cold exposure can be quite effective, depending on the patient.

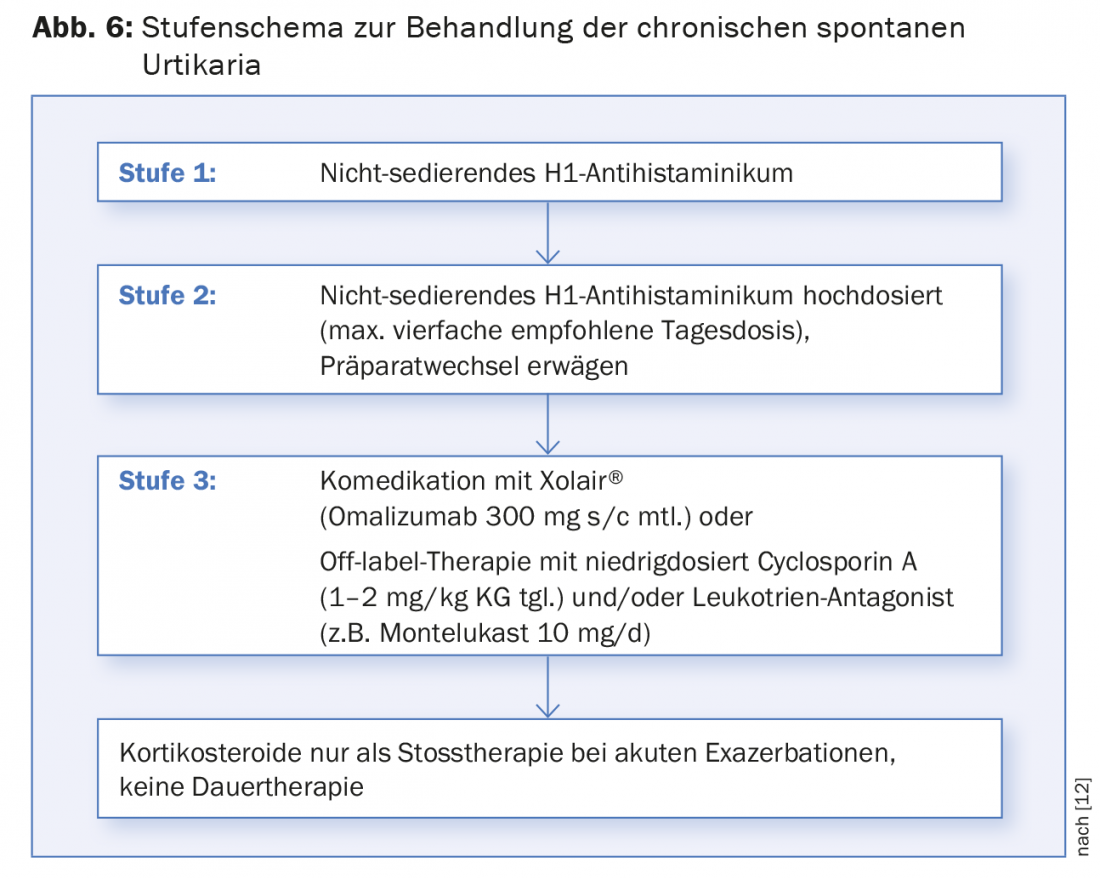

Regardless of the above, the treatment of CSU is primarily symptomatic and is staged (Fig. 6) . Non-sedating H1 antihistamines such as (levo-)cetirizine, (des-)loratadine, fexofenadine or bilastine are considered as basic medications. Sedating first-generation antihistamines (e.g., hydroxyzine, doxepin) or H2 antihistamines (e.g., ranitidine, cimetidine) should no longer be used in combination therapy or should be used only in very selected cases because of side effects and unclear pharmacokinetics. If itching and wheals persist at the standard dose, the recommended daily dose may be increased up to four times. Fexofenadine and bilastine, for which studies in the high-dose range are available and for which no “poor metabolizers” are known (such as for desloratadine), are particularly suitable for this purpose. If there is no improvement despite increasing the dose, switching to an alternative antihistamine on a trial basis is possible, although this is no longer recommended in the guidelines. From our experience, individual response to the various antihistamines sometimes varies.

In case of insufficient response despite baseline treatment with antihistamines, either the use of a leukotriene antagonist [16] such as montelukast or cyclosporine A at a low dose (1-2 mg/kg bw) is an option [17]. However, both are not approved in this indication. It is important to note here that regular monitoring of blood pressure and renal parameters is obligatory during treatment with cyclosporin A. After four months at the latest, the therapy should be reviewed; if necessary, a slow tapering is then possible.

After many years of successful use of the anti-IgE antibody omalizumab (Xolair®) in severe allergic asthma, its efficacy and good tolerability have also been demonstrated in CSU in large-scale studies in Europe and the USA in recent years [18–20]. This ultimately led to the Europe-wide approval of Xolair® in this indication as well in the course of 2014. It is a fixed-dose regimen of 300 mg four weekly, in contrast to asthma, regardless of weight and total IgE titer. Due to the annual drug costs of more than 12,000 CHF and the fact that the drug can only be administered parenterally, the indication for therapy must be well evaluated.

If wheals and pruritus continue to occur with the above treatment measures, a corticosteroid shot (prednisolone 0.5 mg/kg bw/d for 5-7 days) may be tried. Long-term treatment with steroids is not recommended due to known long-term effects. In cases with a biopsy-proven neutrophilic inflammatory component, dapsone has also been shown to be effective. However, it is currently not registered in Switzerland and must be obtained via Germany.

As soon as the urticaria no longer occurs under symptomatic treatment for several months, a slow reduction to the smallest possible dose that is still effective can be made at two- to four-week intervals.

Literature:

- Maurer M, et al: Allergy 2011; 66: 317-330.

- Gaig P, et al: J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 2004; 14(3): 214-220.

- Confino-Cohen R, et al: J Allergy Clin Immunol 2012; 129(5): 1307-1313.

- Ferrer M: J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 2009; 19(Suppl 2): 21-26.

- Beltrani VS: Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2002; 23(2): 147-169.

- Sheikh J: Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2005; 5: 403-407.

- Kulthanan K, et al: J Dermatol 2007; 34: 294-301.

- Amar SM, Dreskin SC: Prim Care 2008; 35: 141-157.

- Guttman-Yassky E, et al: J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2007; 21: 35-39.

- Konstantinou GN, et al: Allergy 2013; 68(1): 27-36.

- Asero R, et al: J Allergy Clin Immunol 2006; 117: 1113-1117.

- Zuberbier T, et al: Allergy 2014; 69(7): 868-887.

- Magerl M, et al: J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2014. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12739.

- Gentinetta T, et al: J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011 Dec; 128(6): 1227-1234.

- Magerl M, et al: Allergy 2010; 65(1): 78-83.

- Wan KS: J Dermatolog Treat 2009; 20: 194-197.

- Vena GA, et al: J Am Acad Dermatol 2006; 55: 705-709.

- Maurer M, et al: N Engl J Med 2013; 368(10): 924-935.

- Kaplan A, et al: J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013; 132(1): 101-109.

- Saini SS, et al: J Invest Dermatol 2015; 135(1): 67-75.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2015; 25(2): 9-14