Questions about brain performance due to subjective complaints or environment-reported cognition problems are increasingly common in primary care consultations. This is due to demographic developments. Dementias increase with age: 75- to 84-year-olds show a prevalence rate of 10.9%, and 85- to 93-year-olds 30% for dementias. Women are affected more often than men. About 5% of dementia diagnoses are in patients younger than 65 who are potentially still in the workforce.

Questions about brain performance due to subjective complaints or environment-reported cognition problems are increasingly common in primary care consultations. This is due to demographic developments. Dementias increase with age: 75- to 84-year-olds show a prevalence rate of 10.9%, and 85- to 93-year-olds 30% for dementias. Women are affected more often than men. Approximately 5% of dementia diagnoses are in patients younger than 65 years who are potentially still in the workforce [1].

According to Alzheimer Switzerland, there are currently around 144,300 dementia sufferers living in Switzerland, and around 30,900 new cases are suspected each year. The figures are very inaccurate, as it is assumed that only just under half of dementia diagnoses have been made correctly. Brain disorders are often misinterpreted as senile forgetfulness and sometimes accepted without consequences.

The financial consequences in Switzerland were estimated at 11.8 billion Swiss francs in 2020. These consist of direct costs for medical examinations and treatments as well as indirect costs for the care of patients. Up to 60% of people with dementia are cared for by their relatives, which has a great impact on their lives (1-3 relatives per patient affected) [2]. These relatives mostly perform unpaid services and are not or hardly compensated financially for this. The real costs attributable to dementia would be many times higher if this volunteer work were paid.

An early diagnosis is of high relevance for the affected person as well as for the treating and caring persons: Be it in order to arrange life accordingly, to be able to carry out an optimal treatment planning, or also to prepare corresponding powers of attorney in time. In addition, potentially reversible causes that are treatable are found in 2-5% of cases, making early and thorough diagnosis essential.

The following is the recommended workup sequence for general practitioners based on the 2018 Swiss Memory Clinics recommendations for the diagnosis of dementia [3].

Definition

Not every memory disorder is dementia, and not every dementia is accompanied by memory impairment. People often mistakenly report “age forgetfulness” and assume that aging per se makes people forgetful. Various neuropsychological studies have shown that short-term memory impairment is not a physiological aging process. There may already be limitations in the various memory functions with increasing age, but these should not impair everyday functionality. Typical age-associated changes in brain performance are an increase in crystalline intelligence (factual knowledge) on the one hand, and a decrease in fluid intelligence (information processing such as accuracy/speed) on the other. Likewise, the “working memory” becomes smaller, so less new information can be stored per time unit. Flexibility in thinking also decreases. Procedural memory, that is, remembering previously learned things such as riding a bicycle or tying shoelaces, usually remains unchanged. Divided attention (doing several things at once, such as talking on the phone while cooking lunch) declines with age. Thus, “age forgetfulness” is either due to delayed processing speed, or if more severe, to a disease (usually Alzheimer’s disease) that needs to be correctly diagnosed [4].

As long as there is “only” memory impairment without any impact on everyday life, one speaks of a mild cognitive disorder or “Mild Cognitive Impairment”, MCI. Progression to dementia is thought to occur in up to 10% of MCI [5].

The definition of the diagnosis “dementia” can be made on the one hand according to the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD, 10th version: ICD-10): “Dementia is a syndrome resulting from a usually chronic or progressive disease of the brain with disturbance of many higher cortical functions, including memory, thinking, orientation, comprehension, calculation, learning ability, language and judgment. Consciousness is not clouded. The cognitive impairments are usually accompanied by changes in emotional control, social behavior, or motivation; occasionally these occur sooner. This syndrome occurs in Alzheimer’s disease, cerebrovascular disorders, and other conditions “primarily or secondarily affecting the brain” (conditions such as Parkinson’s disease, hydrocephalus, or neuroborreliosis) [6].

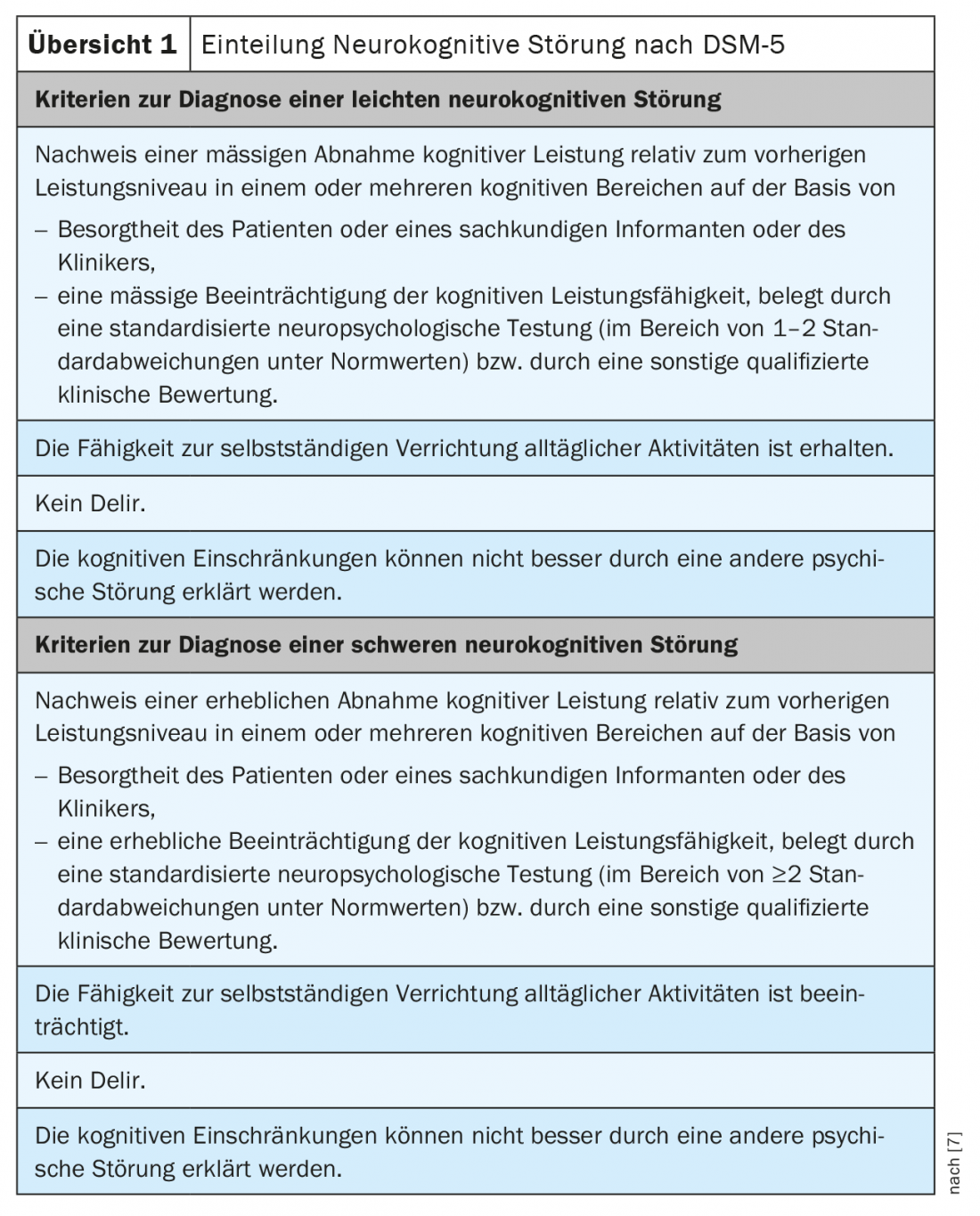

Alternatively, a classification according to DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, version 5) is mainly used in Anglo-Saxon countries. In order to facilitate a simpler etiological classification and at the same time to avoid the stigmatization of the term “dementia”, the DSM-5 refers to neurocognitive disorder. The diagnostic criteria are listed in Overview 1 . This classification allows for different combinations of severity and causes of neurocognitive disorder [7].

In Switzerland, this categorization is already used in specialized memory clinics. In daily dealings with patients, but also with health insurers, for coding or the authorities, the term “dementia syndrome” is still used.

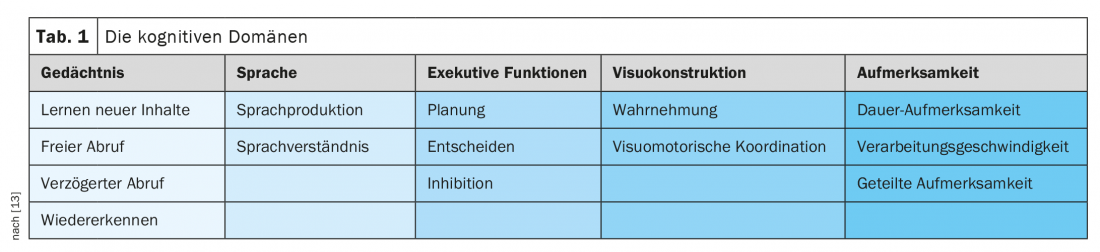

The domains of the mentioned higher cortical functions are shown in Table 1. presented in more detail. Different domains are typically affected in different diseases. For example, extensive neuropsychological testing can often narrow down the causes of dementia based on the cognitive failure profile, provided the dementia is not too advanced and all areas are affected. As an example, it can be mentioned that in Alzheimer’s disease, the memory disorders are often in the foreground. In Parkinson’s dementia, memory impairment is rarely present at onset, but attention and executive functions are impaired early.

As mentioned above, limitations in daily life due to cognitive decline are mandatory for the diagnosis of a dementia syndrome. The severity classification of dementia is based on the need for support in Activities of Daily Living (ADL) and is a clinical assessment that can be supported by the expression of neurocognitive deficits from neuropsychological testing.

Mild dementia syndrome is when there is a selective need for support in the instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs such as handling money, preparing meals). The moderate dementia syndrome requires support in the basic activities of daily living, the BADL, such as personal hygiene, eating, toileting, etc.). In the context of a severe dementia syndrome, one is comprehensively dependent on assistance.

As mentioned above, the prevalence of dementia increases with age. Should all patients then be screened, for example, from the age of 70?

Who and how to clarify?

It is not recommended to screen the entire elderly population for brain performance problems. An examination in the family practice should be performed in the sense of “case-finding” in case of warning signs, so-called “red flags” (review 2) [3].

With previously it is recommended to perform a somato- and psychostatus after a detailed anamnesis and an external anamnesis. It is important to recognize the course and extent of the cognition disorders (fluctuations, continuous change, effects on everyday life). Medication history, as well as questions about sleep disturbances, incontinence, evidence of Parkinson’s disease symptomatology, depressiveness, and noxious agents, are important anamnestic information.

A screening test can be performed well in the office. Whether this is the widely used Mini Mental Status Examination (MMSE according to Folstein) combined with the clock test (UT), the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) or the Dementia Detection Test (DemTect) does not make much difference. The MMSE is not very sensitive in early stages, so combination with the UT is recommended. It is important to provide a quiet testing environment and to compensate for hearing as well as visual difficulties of the patients before testing [3]. Testing should not be performed in hypoglycemic or symptomatically hypotensive patients. If cognitive screening is unremarkable, retesting can be done after 6 to 12 months. However, if the screening test is abnormal, further investigations are recommended to find the cause.

Further clarifications in practice

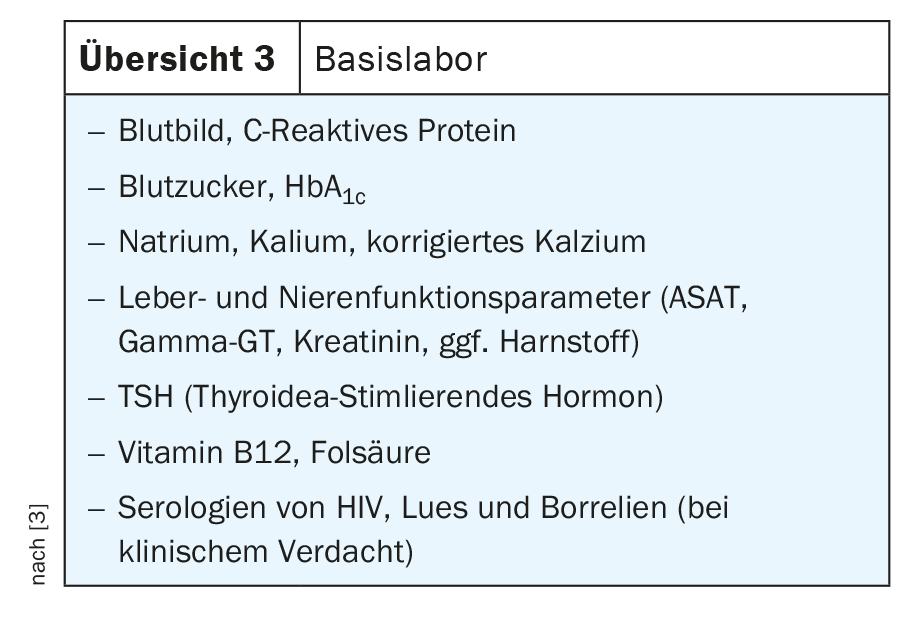

If there are any abnormalities in the screening, further clarifications can be carried out by the family doctor. Thus, an ECG (especially question about arrhythmias, block images, ischemia signs) and basic laboratory testing are recommended. The aim of this is to detect metabolic, infectious or endocrinological cognition disorders. The recommended basic laboratory tests are listed in Overview 3.

Uremia or hypercalcemia are treatable causes of cognition impairment. A check of the cognitive functions in the course can show whether a further dementia clarification is necessary in case of persistence of the symptoms.

Imaging of the neurocranium is formally part of every dementia workup, as treatable causes can also be detected here, such as subdural hematoma or normal pressure hydrocephalus. In addition, based on brain morphology, a conclusion can be drawn about the etiology of dementia (focal atrophy of the hippocampal formation and temporal lobes in Alzheimer’s disease or vascular lesions in vascular dementia).

The gold standard is magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with the question of focal or generalized atrophy, vascular changes, CSF circulatory disturbance, round foci, or if inflammatory changes are suspected. If MRI is not feasible, computed tomography, if possible with contrast, may be considered as an alternative. Functional imaging has its place only in the later course, often on notification by a specialized memory clinic. For example, FDG-PET (18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography) can differentiate between Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia in the presence of focal underutilization.

CSF diagnostics have gained in importance and can be used to differentiate the cause of dementia. CSF puncture is indicated to exclude non-primary degenerative forms of dementia, especially chronic inflammatory CNS diseases (neuroborreliosis, vasculitis for example). Likewise, in cases of rapidly progressive dementia (suspected Creutzfeld-Jakob disease) or as a therapeutic trial in normal pressure hydrocephalus, CSF puncture should be performed as a standard procedure. The constellation of “dementia markers” beta-amyloid 1-42, phospho-tau, and total tau may provide a clue to the etiology of neurodegenerative dementia in the presence of nonconclusive clinic and imaging. It is important to follow the preanalytical recommendations of the respective laboratory [3].

Referral to a memory clinic for detailed neuropsychological testing and interdisciplinary assessment is strongly recommended in young patients. Referral is also appropriate in cases of unclear clinic or atypical presentation, for example, with behavioral disturbances.

Following a cognitive assessment, prompt disclosure of the diagnosis is essential for affected individuals and their families. Information should also be provided about support services. For example, the Alzheimer’s Association can provide advice to sufferers and their families (information can be obtained at www.alzheimer-schweiz.ch). Involving the environment is an important pillar of dementia care.

Prevention

Fortunately, several effective dementia prevention measures have been demonstrated. Thus, both an absolute risk reduction of developing dementia and the risk of progression from MCI to dementia can be achieved.

This prevention includes good blood pressure control and control of cardiovascular risk factors (blood glucose, cholesterol) and sufficient physical activity already pre-morbidly. Stimulating social contacts as well as good school education have a protective effect. The 2015 Finger study showed a positive impact of physical activity, dietary measures, and cardiovascular risk factor control on cognitive function [8]. Nutritional studies such as those on the “MIND diet” also demonstrated a reduction in risk [9]. MIND diet stands for “Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay” and is a mixture of Mediterranean and DASH diet. The Mediterranean diet aims to eat as few processed foods as possible, reducing saturated fat and favoring fresh, whole foods. The DASH diet focuses primarily on encouraging patients to eat low-sodium foods to lower their blood pressure.

The occurrence of depression in older age is associated with increased risk of developing dementia. Whether the depression is an expression of the onset of dementia or the dementia is an effect of the depression has not yet been clarified [10]. There is evidence that depression treatment can delay the progression of MCI to dementia [11].

Finally, it remains to be emphasized that dementias are common in old age and should be diagnosed early and correctly. Many assessment steps can be performed or initiated in the primary care physician’s office (history, screening tests, somato- and psychostatus as well as laboratory tests and cerebral imaging). If the findings become inconclusive or more in-depth care/counseling is needed, it is recommended that a memory clinic be contacted. There, a detailed interdisciplinary assessment is carried out according to current standards and the patients as well as their environment can be competently advised. A list of Swiss memory clinics can be found on the homepage of the association “swiss memory clinics” [12].

Take-Home Messages

- A case-finding strategy for dementia screening is recommended in case of warning signs (subjective memory problems, cognition changes reported by others or new problems, for example, in blood glucose or blood pressure management, delirium that has occurred).

- Cognition problems, whether subjectively perceived or reported by others, should be clarified, as reversible causes are found in up to 5%.

- Whenever possible, an external history should be obtained to detect changes in brain performance or behavior that may not be perceived by affected individuals.

- In addition to history and status, basic laboratory and cerebral imaging are indispensable in the diagnosis of dementia.

- Early referral to a memory clinic for a thorough evaluation is particularly important in young patients and in cases of atypical presentation or evaluation of drug treatment.

Acknowledgement

Many thanks to Prof. Dr. med. Andreas Zeller, Head of the University Center for Family Medicine Beider Basel (uniham-bb), for proofreading and constructive suggestions for improvement.

Literature:

- Swiss Federal Statistical Office, “Costs of Dementia in Switzerland,” www.bag.admin.ch/bag/de/home/zahlen-und-statistiken/zahlen-fakten-demenz.html.

- Alzheimer Switzerland, www.alzheimer-schweiz.ch/fileadmin/dam/Alzheimer_Schweiz/Dokumente/Publikationen-Produkte/07.01D_2020_Zahlen-Demenz-Schweiz-neu.pdf.

- Bürge M, et al: The Swiss Memory Clinics recommendations for the diagnosis of dementia. Praxis 2018; 107(8): 435-451.

- Harada CN, et al: Normal cognitive aging. Clin Geriatr Med 2013; 29(4): 737-752.

- Campbell NL, et al: Risk Factors for the Progression of Mild Cognitive Impairment to Dementia. Clin Geriatr Med 2013; 29(4): 873-893.

- ICD-10, www.dimdi.de/static/de/klassifikationen/icd/icd-10-gm/kode-suche/htmlgm2020/block-f00-f09.htm; accessed 04/18/2021.

- Falkai P, et al: American Psychiatric Association (APA): Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM-5 2015.

- Ngandu T, et al: A 2-year multidomain intervention of diet, exercise, cognitive training, and vascular risk monitoring versus control to prevent cognitive decline in at-risk elderly people (Finger), a randomized controlled trial. Lancet 2015; 385: 2255-2263.

- Morris MC, et al: MIND diet associated with reduced incidence of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 2015; 11(9): 1007-1014.

- Singh-Manoux A, et al: Trajectories of Depression before Diagnosis of Dementia. JAMA Psychiatry 2017; 74(7): 712-718.

- Dafsari FS, Jessen F: Depression- an underrecognized target for prevention of dementia in Alzheimer’s disease. Translational Psychiatry 2020; 10: 160-173.

- www.swissmemoryclinics.ch

- Oedekoven C, Dodel R: Neurology up2date 2019; 2 (1): 91-105.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2022; 20(2): 6-9.