Mental disorders frequently occur in the context of cardiovascular diseases and can have a negative impact on the somatic prognosis. As a rule, however, effective approaches exist to treat these complaints. Specific recommendations should be taken into account.

You can take the CME test in our learning platform after recommended review of the materials. Please click on the following button:

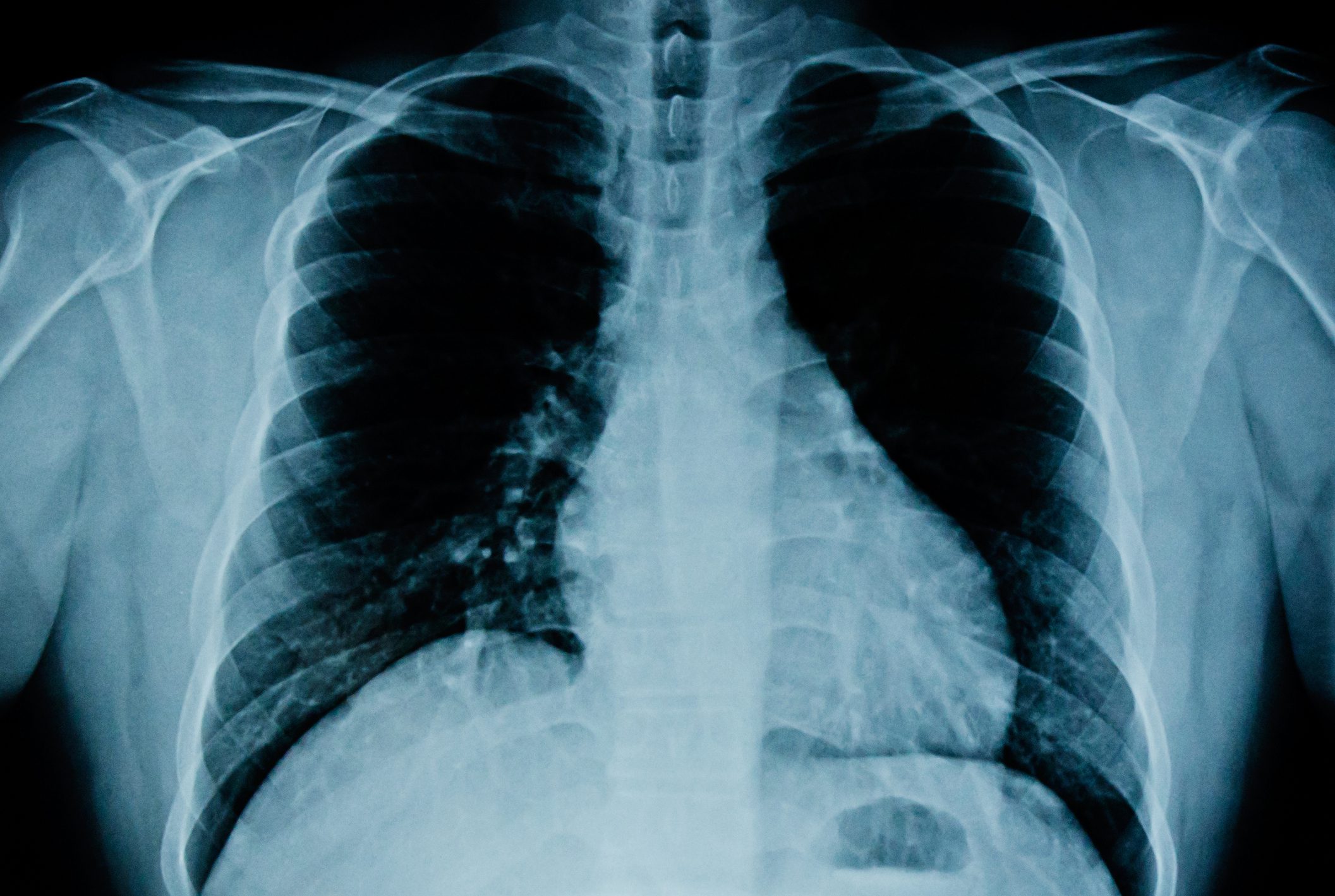

Mr. M. is 63 years old and was treated for a myocardial infarction by means of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). One and a half weeks later, he began an outpatient cardiovascular rehabilitation program. During rehabilitation, cardiovascular risk factors should be optimally adjusted in order to reduce the likelihood of a recurrence. This includes consideration of potential psychosocial impact factors. For this reason, the cardiologist also addresses the patient’s current mental state during the initial medical examination and a standardized questionnaire screening on psychological complaints is carried out. Mr. M. stated that he suffered from recurrent paroxysmal anxiety, insomnia, severe worry and low mood. The questionnaire screening confirmed these symptoms and showed a clinically relevant severity compared to the norm population. Based on these findings, the cardiologist introduced the patient to the cardiopsychology consultation and, with the patient’s consent, organized an initial consultation there.

The main task of specialized cardiopsychological care is to treat comorbid mental disorders in people with cardiovascular disease in order to reduce the level of suffering and improve the health prognosis. Most treatments take place in an outpatient setting, although specialized centers may also offer appropriate consultation and liaison services as well as inpatient services.

Psychological complaints such as those reported by Mr. M. are common and occur in the context of various cardiovascular diseases (e.g. acute or chronic coronary syndrome, heart failure, rhythmogenic diseases, congenital heart defects). Case examples from cardiopsychology are diverse and the patient population ranges from children to the elderly (Overview 1). Mental disorders that frequently occur in this context are panic disorder (F41.0), agoraphobia (F40.0X), depressive episodes (F32.XX), adjustment disorders (F43.2X), post-traumatic stress disorder (F43.1), somatoform autonomic dysfunction (F45.30), and somatic stress disorder (sensu DSM-5, reference code F45.1) [1].

Prevalences

The annual prevalence of clinically relevant psychological complaints is around 40% across all cardiovascular disease groups [2,3]. Epidemiological studies have so far mainly focused on anxiety disorders and depressive disorders. The prevalence of both groups of disorders is significantly higher in people with cardiovascular disease than in the general population.

More differentiated analyses show that generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder and agoraphobia are the most common anxiety disorders. Compared to the general population, the prevalence is 2.5 to 4.5 times higher [4]. The point prevalence rates for comorbid depressive episodes are 20% to 30% [5], which corresponds to a 2- to 3-fold increase compared to the general population [6].

Furthermore, studies indicate that the prevalence rates are related to the severity of the cardiovascular disease. It has been shown, for example, that the point prevalence of depressive disorders in people with heart failure increases with increasing cardiac symptoms. People with mild cardiovascular symptoms (NYHA stage I) have a prevalence of 11%, whereas people with severe cardiovascular symptoms (NYHA stage IV) have a prevalence of 42% [7].

Prognostic relevance

Mental disorders are not only associated with suffering, but can also have a significant impact on the course of cardiovascular diseases, with negative effects on morbidity and mortality.

Accordingly, a study of 26,641 people showed that the risk of death increases significantly if depressive and anxiety symptoms are present for 12 months after surviving a myocardial infarction. The risk of cardiovascular death was increased by 46% and the risk of non-cardiovascular death by 54% [8]. Similarly, people with heart failure and comorbid depressive symptoms also have a significantly higher risk of mortality and secondary cardiovascular events (approx. 1.5 to 2.5 times higher) [9].

Furthermore, meta-analytical data show that symptoms of depression are associated with a 57% increased likelihood of adverse events and 43% increased risk of death after PCI [10]. A negative influence of depression symptoms on mortality has also been shown in aortocoronary bypass operations [11].

Along with the negative impact on somatic prognosis, people with cardiovascular diseases and mental disorders also have significantly higher rates of rehospitalization and treatment costs [12–14].

Mechanisms of action

Interactions between mental disorders and cardiovascular diseases can be explained by physiological and behavioral processes (Fig. 1) . Associated physiological processes can promote the combined occurrence of cardiovascular diseases and mental disorders. For example, a persistent depressive disorder can cause changes in the autonomic nervous system that lead to increased sympathetic tone and an increased cortisol level, which has a negative effect on the cardiovascular system in terms of overload. Conversely, prolonged increased activation of the cardiovascular system and the autonomic nervous system can contribute to the development of a mental disorder [4,15].

Other such processes include changes in platelet receptors and function, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 and fibrinogen and associated coagulation processes, endothelial function, proinflammatory cytokines (e.g. interleukin-6 and interleukin-10 ), genetic factors (e.g. serotonin transporter gene), reduced parasympathetic tone and dysfunctional endocytosis.e.g. interleukin-6 [IL-6] and interleukin-10 [IL-10]), genetic factors (e.g. serotonin transporter gene), reduced parasympathetic tone and dysfunctional endocrine feedback regulation in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis [16–18].

The same applies to behavioral mechanisms that can occur more frequently in both disease groups and promote the risk of disease development or worsening in both directions. Examples include nicotine consumption, an unhealthy diet, physical inactivity and medication adherence [2].

Treatment recommendations

Mental disorders associated with cardiovascular disease are treated both psychotherapeutically and psychopharmacologically, depending on the disorder and its severity. Treatment is generally based on the classic guidelines for mental disorders. However, certain aspects of the treatment of this specific patient group should be given special consideration and adapted.

If there are uncertainties regarding adverse cardiovascular effects in the treatment of mental disorders, consultation with cardiology specialists is essential. Particular caution is required in the case of complex cardiovascular diseases. Examples of such clinical pictures are severe heart failure with possible transplantation or mechanical heart support systems (e.g. Left Ventricular Assist Device, LVAD), malignant arrhythmias and complex congenital heart defects. In such cases, treatment in a specialized center is recommended if there is a comorbid mental disorder. This enables an effective exchange between different specialist areas of cardiovascular medicine and clinical psychology/psychiatry. The specialist staff at these centers have in-depth knowledge of both mental disorders and cardiovascular diseases. This expertise enables specialized treatment of the psychological symptoms, which is adapted to the needs of this specific patient group both psychopharmacologically and psychotherapeutically. The most important specific treatment recommendations for this context are summarized in Overview 2 .

With regard to psychopharmacological treatments, a possible prolongation of the QTc interval, effects on anticoagulation and on blood pressure are of particular relevance. Prolongation of the QTc interval can in certain cases lead to life-threatening ventricular fibrillation due to delayed ventricular repolarization. Preparations that can prolong the QTc interval are selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), selective serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SSNRIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), antipsychotics of the 1. and 2nd generation and lithium [19,20]. Particularly in people with rhythmogenic underlying diseases (e.g. long QT syndrome), consultation with cardiology specialists should take place and appropriate ECG checks should be carried out.

Anticoagulation must be taken into account, especially with serotonergic preparations, as these can increase the risk of bleeding due to a serotonin-related reduction in platelet activation and aggregation. Current reviews show that the risk of bleeding increases by around 35% to 45% in people who take both an SSRI and antithrombotic therapy (anticoagulants or platelet aggregation inhibitors) compared to people who only receive antithrombotic therapy. Caution should therefore be exercised when prescribing an SSRI for people receiving antithrombotic therapy. In the case of strong anticoagulation (e.g. with a mechanical heart valve), blood coagulation should be closely monitored during the dosing phase [21,22].

Changes in blood pressure must be taken into account, particularly with noradrenergic preparations. These include noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (NRIs), SSNRIs and noradrenaline and dopamine reuptake inhibitors (NDRIs) [19]. This is extremely important for people in whom a significant rise in blood pressure can be acutely threatening, such as those with connective tissue diseases that can lead to aortic dissections (e.g. Marfan syndrome).

The use of TCAs and stimulants is generally not recommended for people with cardiovascular disease. TCAs show a comparatively high risk of QTc interval prolongation. In addition, the anticholinergic effect of these drugs may be detrimental in people with cardiovascular disease. The main reason for this is possible additional stress on the cardiovascular system due to the inhibition of the parasympathetic system by blocking the effect of acetylcholine on muscarinic acetylcholine receptors as well as potential changes in blood pressure and vasodilation/constriction [3,19].

Stimulants such as methylphenidate, which are used to treat attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), have been reported to cause sudden death in people with cardiovascular disease. Accordingly, cardiovascular disease is considered a contraindication, although recent studies show that the risk may have been overestimated to date [23,24]. Alternatively, the substances bupropion or agomelatine could be considered as pharmacological support. These tend to have a lesser effect on ADHD symptoms, but offer a significantly more favorable cardiovascular risk profile. However, the evidence base for the use of these preparations as an alternative for ADHD is still very limited [25–29].

It should also be noted that, according to the current European cardiovascular guidelines, the administration of SSRIs, SSNRIs and TCAs with a IIIB recommendation is not recommended in people with heart failure [3]. This is because larger studies have shown a slight increase in mortality with the administration of these preparations and no empirically proven effect on depressive symptoms. Thus, based on the current state of knowledge, there is no legitimate empirical cost-benefit ratio [30–32]. However, the individual case must always be considered carefully and the potential benefit and the expected risk must be weighed up individually and on an interdisciplinary basis in order to make the best possible use of the treatment options [28].

Special attention must also be paid to the use of certain non-drug psychotherapeutic treatment elements in this patient group. This concerns exposure therapies (e.g. for agoraphobia, post-traumatic stress disorder) in which a strong emotional and associated physiological activation is generated through in-vivo or in-sensu confrontation [33]. This intervention is not recommended in people with coronary heart disease and not fully revascularized vessels or in people in whom strong vegetative activation can be acutely threatening (e.g. certain malignant arrhythmias, or with the potential for aortic dissection). Consultation with the cardiology specialist is strongly recommended in such cases. Possible therapeutic alternatives are metacognitive approaches and acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) interventions. These focus on changing the way people deal with thoughts and emotions that arise and are physiologically less activating than exposure therapies, although further evidence is needed to ensure the empirical effectiveness of these alternatives in this context [34,35].

Effectiveness of interventions

Non-pharmacological psychotherapeutic interventions show a relevant degree of effectiveness with regard to psychological symptoms in this patient population, whereby cognitive-behavioral therapeutic approaches have primarily been investigated to date. With regard to depression and anxiety, reviews show a meta-analytical effect of approx. 0.3 (SMD) in each case [36–39]. It has also been shown that psychological interventions can be associated with a reduction in mortality of up to 21% within ten years [37]. However, the effect of psychological interventions on somatic morbidity and mortality still requires further research.

Psychopharmacological therapies also have an effect on the psychological symptoms in this patient group and there are also indications of positive influences on the somatic course [3]. However, recent data also suggest potentially negative effects of long-term psychopharmacological treatments on the cardiovascular system [40].

The current data does not show any general superiority of one of the two forms of treatment (medication vs. non-medication) in people with cardiovascular disease and comorbid mental disorders [41]. The best possible treatment must therefore be selected in consultation with the person concerned and in an interdisciplinary exchange, taking into account the individual symptoms, the contextual conditions and relevant treatment recommendations. Flexible and integrative treatment with good and regular progress evaluation is of central importance.

Summary

Mental disorders occur comparatively frequently in people with cardiovascular disease. Mental disorders are prognostically relevant and can have a negative impact on the course of cardiovascular diseases. The interactions between mental disorders and cardiovascular diseases are due to physiological processes (e.g. hormonal and inflammatory processes) and behavioral processes (e.g. exercise behavior, substance use). The treatment of mental disorders in people with cardiovascular disease can be carried out both pharmacologically and psychotherapeutically, whereby specific treatment recommendations and interdisciplinary agreements must be taken into account. Particularly in the case of more complex cardiovascular diseases and comorbid mental disorders, treatment should be carried out in specialized centers wherever possible. Thanks to their specialized focus, these centers facilitate interdisciplinary collaboration and can offer more specific treatment options for this patient group. Psychotherapeutic and psychopharmacological interventions are effective in reducing psychological complaints. Both treatment approaches also showed initial indications of positive effects on the cardiovascular course.

Take-Home-Messages

- Mental disorders frequently occur in the context of cardiovascular diseases.

- Mental disorders can have a negative impact on the somatic prognosis.

- There are effective approaches for treating psychological complaints.

- Specific recommendations must be taken into account when treating psychological complaints.

- People with complex cardiovascular diseases and comorbid mental disorders should be treated in specialized centers.

Literature:

- Herrmann-Lingen C, Albus C, Titscher G: Psychocardiology. A practical guide for doctors and psychologists Cologne: Deutscher Ärzte-Verlag. 2008.

- Albus C, Waller C, Fritzsche K, et al: Significance of psychosocial factors in cardiology: update 2018: Position paper of the German Cardiac Society. Clin Res Cardiol 2019; 108(11): 1175-1196.

- Visseren FLJ, Mach F, Smulders YM, et al: 2021 ESC Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Eur Heart J 2021; 42(34): 3227-3337.

- Pedersen SS, Von Känel R, Tully PJ, Denollet J: Psychosocial perspectives in cardiovascular disease. European journal of preventive cardiology 2017; 24(3_suppl): 108-115.

- Gold SM, Kohler-Forsberg O, Moss-Morris R, et al: Comorbid depression in medical diseases. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2020;6(1): 69.

- Wittchen HU, Jacobi F, Rehm J, et al: The size and burden of mental disorders and other disorders of the brain in Europe 2010. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2011; 21(9): 655-679.

- Rutledge T, Reis VA, Linke SE, et al: Depression in heart failure a meta-analytic review of prevalence, intervention effects, and associations with clinical outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48(8):1527-37.

- Lissaker CT, Norlund F, Wallert J, et al: Persistent emotional distress after a first-time myocardial infarction and its association to late cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular mortality. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2019; 26(14): 1510-1518.

- Sbolli M, Fiuzat M, Cani D, O’Connor CM: Depression and heart failure: the lonely comorbidity. Eur J Heart Fail 2020; 22(11): 2007-2017.

- Zhang WY, Nan N, Song XT, et al: Impact of depression on clinical outcomes following percutaneous coronary intervention: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2019; 9(8): e026445.

- Geulayov G, Novikov I, Dankner D, Dankner R: Symptoms of depression and anxiety and 11-year all-cause mortality in men and women undergoing coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery. J Psychosom Res. 2018; 105: 106-114.

- Frasure-Smith N, Lespérance F, Gravel G, et al: Depression and health-care costs during the first year following myocardial infarction. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 2000: 471-478.

- Jha MK, Qamar A, Vaduganathan M, et al: Screening and Management of Depression in Patients With Cardiovascular Disease: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;73(14): 1827-1845.

- Vaccarino V, Badimon L, Bremner JD, et al: Depression and coronary heart disease: 2018 position paper of the ESC working group on coronary pathophysiology and microcirculation. Eur Heart J 2020; 41(17): 1687-1696.

- Hare DL, Toukhsati SR, Johansson P, Jaarsma T: Depression and cardiovascular disease: a clinical review. Eur Heart J 2014; 35(21): 1365-1372.

- Meyer T, Stanske B, Kochen MM, et al.: Serum levels of interleukin-6 and interleukin-10 in relation to depression scores in patients with cardiovascular risk factors. Behav Med 2011;37(3): 105–112.

- Liu RH, Pan JQ, Tang XE, et al.: The role of immune abnormality in depression and cardiovascular disease. J Geriatr Cardiol 2017; 14(11): 703–110.

- Grippo AJ, Johnson AK: Stress, depression and cardiovascular dysregulation: a review of neurobiological mechanisms and the integration of research from preclinical disease models. Stress 2009; 12(1): 1–21.

- Pina IL, Di Palo KE, Ventura HO: Psychopharmacology and Cardiovascular Disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018; 71(20): 2346–2359.

- Mehta N, Vannozzi R: Lithium-induced electrocardiographic changes: A complete review. Clin Cardiol 2017; 40(12): 1363–1367.

- Nochaiwong S, Ruengorn C, Awiphan R, et al.: Use of serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants and the risk of bleeding complications in patients on anticoagulant or antiplatelet agents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Med 2022; 54(1): 80–97.

- Rahman AA, He N, Rej S, et al.: Concomitant Use of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors and Oral Anticoagulants and Risk of Major Bleeding: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Thromb Haemost 2023; 123(1): 54–63.

- Garcia-Argibay M, Burkner PC, Lichtenstein P, et al.: Methylphenidate and Short-Term Cardiovascular Risk. JAMA Netw Open 2024;7(3): e241349.

- Jackson JW: The cardiovascular safety of methylphenidate. BMJ 2016; 353: i2874.

- Verbeeck W, Bekkering GE, Van den Noortgate W, Kramers C: Bupropion for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017; 10(10): CD009504.

- Salardini E, Zeinoddini A, Kohi A, et al.: Agomelatine as a Treatment for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in Children and Adolescents: A Double-Blind, Randomized Clinical Trial. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2016;26(6): 513–519.

- Niederhofer H: Treating ADHD with agomelatine. J Atten Disord 2012; 16(4): 346–348.

- Ladwig KH, Baghai TC, Doyle F, et al.: Mental health-related risk factors and interventions in patients with heart failure: a position paper endorsed by the European Association of Preventive Cardiology (EAPC). Eur J Prev Cardiol 2022; 29(7): 1124–1141.

- Behlke LM, Lenze EJ, Carney RM: The Cardiovascular Effects of Newer Antidepressants in Older Adults and Those With or At High Risk for Cardiovascular Diseases. CNS Drugs 2020; 34(11): 1133–1147.

- He W, Zhou Y, Ma J, et al.: Effect of antidepressants on death in patients with heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart Fail Rev 2020;25(6): 919–926.

- Angermann CE, Gelbrich G, Stork S, et al: Effect of Escitalopram on All-Cause Mortality and Hospitalization in Patients With Heart Failure and Depression: The MOOD-HF Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2016; 315(24): 2683-2693.

- O’Connor CM, Jiang W, Kuchibhatla M, et al.: Safety and efficacy of sertraline for depression in patients with heart failure: results of the SADHART-CHF (Sertraline Against Depression and Heart Disease in Chronic Heart Failure) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010; 56(9): 692–699.

- Bandelow B, Aden I, Alpers GW, et al.: Deutsche S3-Leitlinie Behandlung von Angststörungen, Version 2 (2021). 2021.

- Wells A, Reeves D, Heal C, et al.: Evaluating Metacognitive Therapy to Improve Treatment of Anxiety and Depression in Cardiovascular Disease: The NIHR Funded PATHWAY Research Programme. Front Psychiatry 2022; 13: 886407.

- Rashidi A, Whitehead L, Newson L, et al.: The Role of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy in Cardiovascular and Diabetes Healthcare: A Scoping Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;1 8(15).

- Reavell J, Hopkinson M, Clarkesmith D, Lane DA: Effectiveness of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Depression and Anxiety in Patients With Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Psychosom Med 2018; 80(8): 742–753.

- Richards SH, Anderson L, Jenkinson CE, et al.: Psychological interventions for coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;4(4): CD002902.

- Chernoff RA, Messineo G, Kim S, et al.: Psychosocial Interventions for Patients With Heart Failure and Their Impact on Depression, Anxiety, Quality of Life, Morbidity, and Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Psychosom Med 2022; 84(5): 560–580.

- Das A, Roy B, Schwarzer G, et al: Comparison of treatment options for depression in heart failure: A network meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res 2019; 108: 7-23.

- Cao H, Baranova A, Zhao Q, Zhang F: Bidirectional associations between mental disorders, antidepressants and cardiovascular disease. BMJ Ment Health 2024; 27(1).

- Zambrano J, Celano CM, Januzzi JL, et al.: Psychiatric and Psychological Interventions for Depression in Patients With Heart Disease: A Scoping Review. J Am Heart Assoc 2020;9(22): e018686.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2024; 19(10): 4–8