In old age, complaints of the hip are a frequent reason for presentation to the family doctor. The earlier the correct diagnosis is made, the greater the treatment options. However, radiological changes do not necessarily correlate with the extent of symptoms and clinical presentation.

With increasing age, complaints in the area of the hip are a frequent reason for presentation to the family doctor. In addition to various diseases from the different disciplines, especially from the surgical, gynecological and urological fields, multiple pathologies from the orthopedic-traumatological spectrum must be considered as differential diagnoses. As often the primary point of contact, the family doctor takes a key position here for the further course.

The earlier the correct diagnosis is made, the greater the treatment options. It can also avoid unnecessary treatments or even unnecessary surgeries. Only a targeted history taking and physical examination with optional diagnostics can weigh the wide spectrum of possible differential diagnoses. Narrowing down the diagnosis, if necessary, allows for timely and accurate specialist referral. It is obligatory to follow up with adequate advanced diagnostics and the beginning of effective therapy.

Cause of hip pain: coxarthrosis around 40%.

Wear and tear of the cartilage leads to painful inflammation in the hip joint. The first warning signs are a morning start-up pain with pulling discomfort in the groin, in the area of the ventral medial thigh, sometimes as far as the knee, a feeling of pressure or pain in the buttocks. Later on, muscle tension and movement restrictions are added and maintain the negative spiral of complaints.

An important differential diagnosis of coxarthrosis is arthritis. Both septic arthritis and arthritis of the rheumatic type can lead to rapid cartilage damage if left untreated.

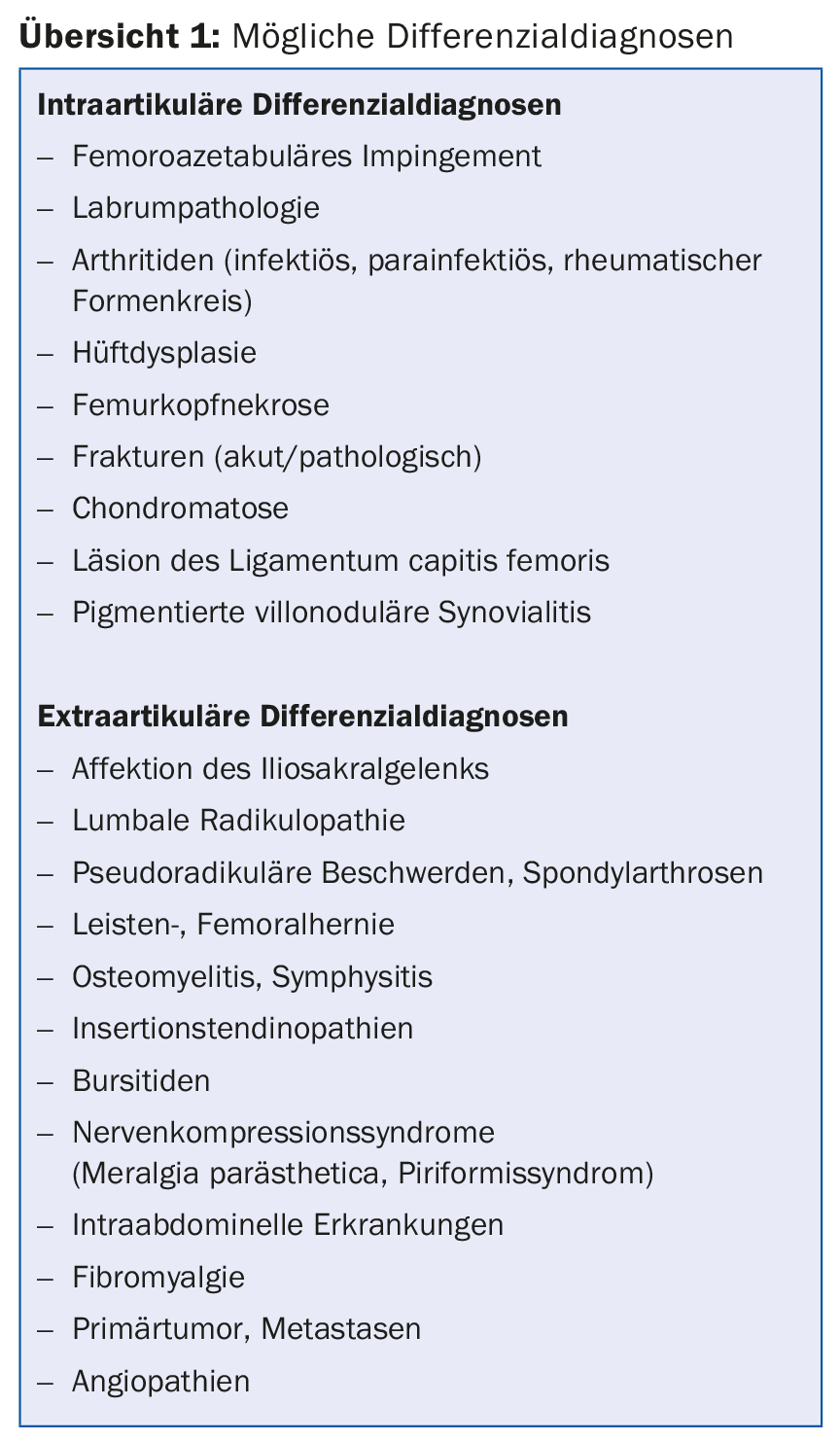

Overview 1 shows possible differential diagnoses.

Coxarthrosis

In most cases, however, the complaints are based on progressive arthrosis. Approximately 5% of the population will develop symptomatic coxarthrosis in their lifetime, with an increasing trend as life expectancy increases. The etiology of coxarthrosis is based on a multifactorial genesis. Mechanical risk factors include post-traumatic form abnormalities, hip dysplasia, Perthes disease, epiphyseolysis capitis femoris, and femoroacetabular impingement. In addition to age and genetic disposition, numerous other risk factors have a negative influence on cartilage metabolism and promote the degenerative process: sporting or occupational overuse or misuse, obesity, lack of exercise, infections, metabolic diseases, collagenoses, and rheumatic diseases. Thus, arthrosis-related problems can occur even well before retirement due to forced wear and tear of the joint partners. In addition, ever larger segments of the population are taking advantage of cultural offerings, travel opportunities and sporting activities, which presupposes the existence of pain-compensated mobility in order to maintain subjective quality of life.

Diagnostics

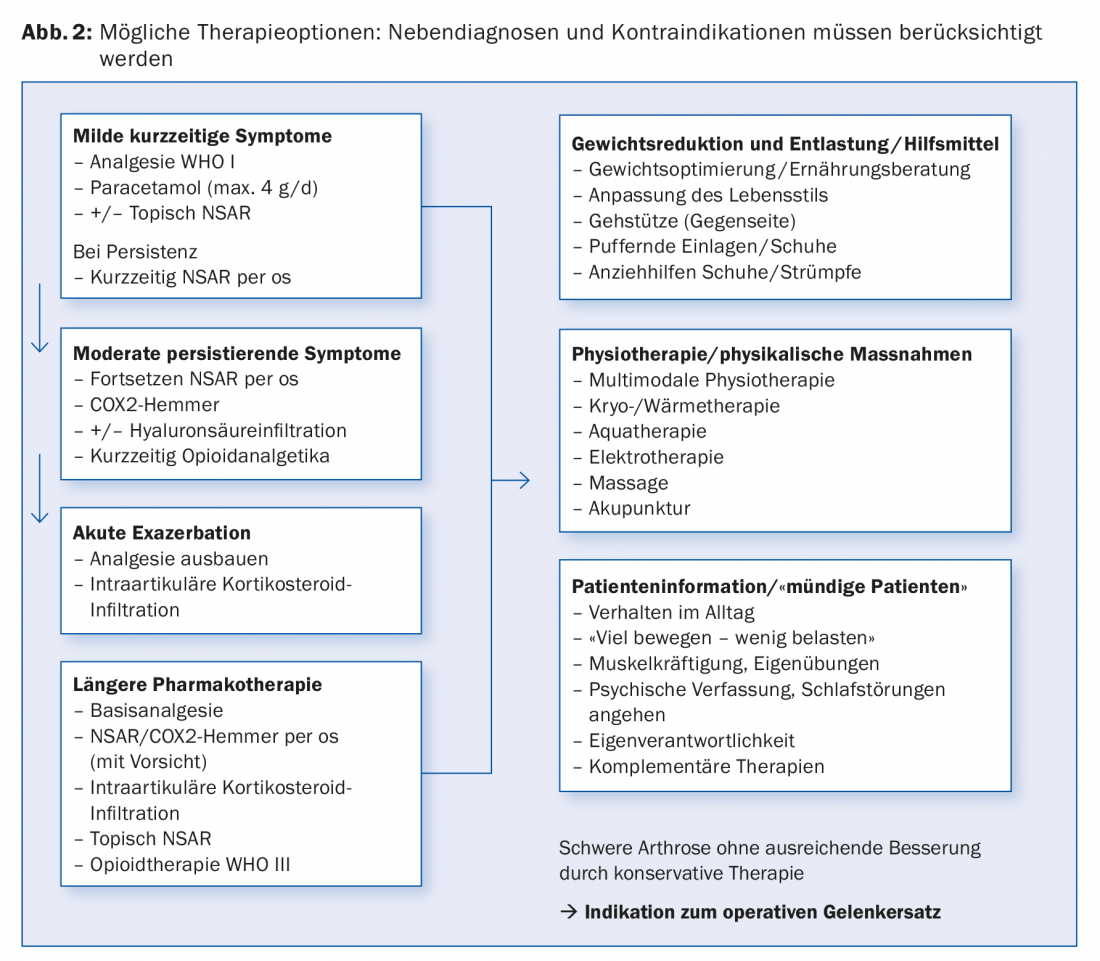

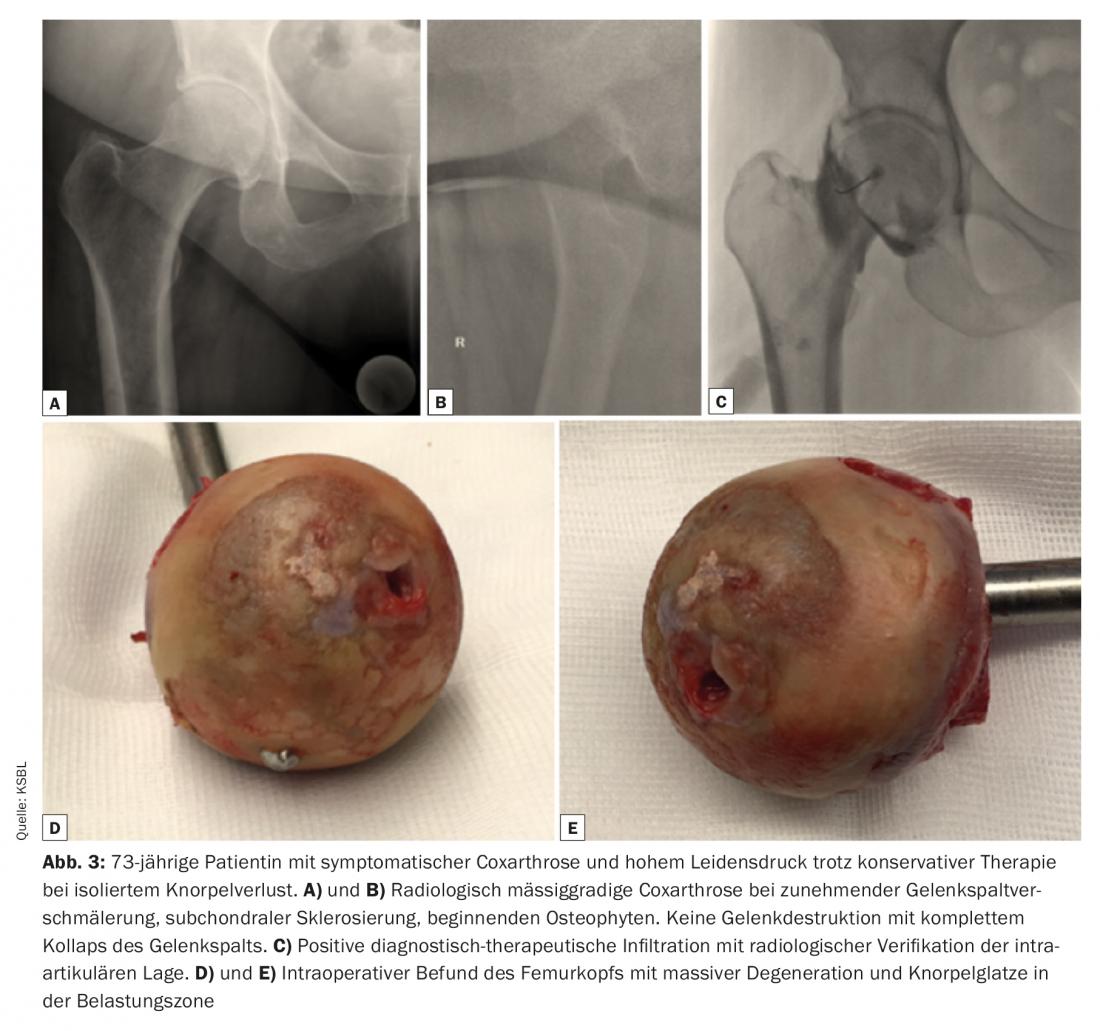

Sufficient clinical and radiologic evaluation usually allows differential diagnosis and staging. Cross-sectional imaging may be indicated as a supplement. Even a positive diagnostic therapeutic infiltration can corroborate or exclude a coxogenic cause in differential diagnostic considerations.

The hip joint examination procedure includes:

- Medical history (pain location, onset, character, onset, exertion, rest pain, trauma, walking distance, concomitant complaints, secondary diagnoses, activity).

- Inspection (statics, soft tissues, gait pattern, leg length)

- Palpation of specific landmarks

- Range of motion

- Assessment of neurology and blood flow

- Special provocation and functional tests.

The basic radiological diagnosis for hip joint disorders is the pelvic a.p. radiograph plus a second level usually as an axial radiograph. A common radiological classification of degenerative joint disease according to Kellgren and Lawrence is:

- Grade I: Minor subchondral sclerosis, no osteophytes.

- Grade II: Incipient osteophytes, moderate joint space narrowing, subchondral sclerosis.

- Grade III: Pronounced osteophytes, joint space narrowing, irregularities of the joint surfaces

- Grade IV: Extensive joint space narrowing to destruction, cysts, femoral head deformity.

Radiological changes do not necessarily correlate with the extent of hip symptoms and clinical presentation (Fig. 1).

Therapy of coxarthrosis

Therapeutic goals are to reduce and eliminate osteoarthritis pain, reduce and eliminate secondary inflammation, improve function, and eliminate or delay osteoarthritis progression.

Primary prevention is also important to prevent the development of osteoarthritis and to reduce risk factors that can be influenced in addition to constitutional factors. These include reduction of excess weight, avoidance of stresses that damage joints (sports medicine or occupational medicine assessment), optimal adjustment of metabolic disorders. In addition, timely diagnosis and treatment of form disorders such as hip dysplasia and femoroacetabular impingement are essential, as they are pathomorphologically an important mechanical cause for the development of coxarthrosis. In particular, the comprehensive sonographic assessment of infant hips according to Graf as part of the screening examinations makes early and sufficient measures for the therapy of hip dysplasia possible today.

Secondary prevention to prevent progression of osteoarthritis continues to include promotion of regular exercise, reduction of obesity, patient education, strengthening of the muscles that support the joint, and, if necessary, joint-preserving interventions such as repositioning osteotomies.

What applies to tertiary prevention to prevent secondary damage in manifest osteoarthritis? Pain and increasing immobility, in addition to restrictions on professional and private performance, in turn promote obesity and a variety of medical conditions. The conservative therapy spectrum includes topical, medicinal and physiotherapeutic measures for symptomatic therapy and preservation of joint function. In the case of advanced findings and persistence of symptoms despite conservative therapy, surgical joint replacement follows.

An overview of the possible therapy options is given in Figure 2.

The optimal time of surgery

There is currently a public debate about whether surgery should be performed too early or too quickly – also in the case of endoprosthetic joint replacement. This discussion is important, but it also needs to be controversial. In addition to economic, socio-political interests and objective radiological findings, the informed patient with his or her wish for treatment, clinically objectifiable and subjective suffering pressure must also be considered. In some cases, this also leads to uncertainty among patients and subsequent referrals, so that some patients end up in a long, sometimes cost-intensive, sometimes complication-ridden course (due, for example, to long-term analgesic use as well as health and social consequences due to increasing immobilization). If correctly indicated, implantation of a total endoprosthesis is nowadays a low-risk routine operation with high patient satisfaction. Long-term success rates and durability are well supported by registry data. Modern “fast track” concepts, including preoperative physiotherapeutic assessment, minimally invasive muscle-sparing access routes, administration of tranexamic acid and short inpatient stays, allow mobilization under full weight-bearing already on the day of surgery. As a result, blood losses requiring transfusion and peri- and postoperative medical complications such as urinary tract infections, pneumonia and thrombosis are rare.

The optimal time for surgery depends individually on objective factors such as joint status, age, walking distance, and limited mobility, as well as personal factors such as activity requirements, willingness to undergo surgery, level of suffering, expectations, and professional situation.

At least three to six months of conservative therapy should be mandatory after the onset of symptoms. Irrespective of age, the indication for joint replacement should be discussed in cases of advanced osteoarthritis and causally confirmed coxogenic osteoarthritis symptoms with a reduction in quality of life despite multimodal conservative therapy (Fig. 3).

Standing times of the hip prosthesis and reasons for a prosthesis change

Abrasion is caused by movement of the joint partners. Abrasion particles can lead to aseptic loosening after years due to inflammatory reactions. This results in the loss of the connection between the prosthesis and the bone. In the past, previous generations of polyethylene or metal-on-metal bearing couples sometimes caused pronounced tissue damage with large defects. Loosening can affect the cup, the prosthesis stem or both components. Ceramic bearing couples have only low abrasion values, but can break and cause noise. The “ideal prosthesis” that leads to the best results for all patients equally does not exist. Depending on age, bone quality and loading situation, the best implant or material for the individual situation must be selected with the correct anchoring technique.

Reasons for a necessary prosthesis change are wear and loosening, osteolyses, dislocations, periprosthetic fractures and infections.

International registry data show revision rates of 0.4-0.8%. Thus, it can be said that in patients who receive a prosthesis at the age of 50, at the age of 70 the artificial joint still functions well in almost 85%, and at the age of 90 it still functions well in about 80%. The older patients are at the time of prosthesis implantation, the more likely the joint will outlive the patient. Consequently, if the patient is approximately 70 years of age at primary implantation, the probability of survival of the artificial joint at 90 years is approximately 90%. Thus, postponing surgery is no longer advisable for a given indication, since the perioperative risk increases with further increasing age and concomitant diseases.

Take-Home Messages

- Femoroacetabular impingement is pathomorphologically an important mechanical cause of coxarthrosis.

- Radiologic signs of coxarthrosis include subchondral sclerosis, osteophytes, joint space narrowing, and boulder cysts.

- Radiographic changes do not necessarily correlate with the extent of hip symptoms and clinical presentation.

- When correctly indicated, implantation of a total endoprosthesis is a low-risk operation with high patient satisfaction.

Further reading:

- Martin HD, Palmer IJ: History and physical examination of the hip: the basics. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2013; 6: 219-225.

- Kellgren JH, Lawrence JS: Radiological assessment of osteoarthrosis. Ann Rheum Dis 1957; 16: 494-502.

- Bohndorf K, et al: [S3 Guideline. Part 1: Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis of Non-Traumatic Adult Femoral Head Necrosis]. Z Orthop Trauma 2015; 153: 375-386.

- Ganz R, et al: The etiology of osteoarthritis of the hip: an integrated mechanical concept. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2008; 466(2): 264-272.

- Clinical Guideline Centre (UK): Osteoarthrosis: Care and Management in Adults. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK) 2014.

- Graf R: Sonography of the infant hip and therapeutic consequences. 6th ed. Stuttgart: Thieme 2010.

- The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners: Guideline for the non-surgical management of hip and knee osteoarthritis. 2009.

- Hansen TB: Fast track in hip arthroplasty. EFORT Open Rev 2017; 2(5): 179-188.

- Müller M, et al: [Diagnosis and therapy of particle disease in total hip arthroplasty]. Z Orthop Trauma 2015; 153(2): 213-229.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2018; 13(3): 30-35