Even though compression therapy is a rather unpopular therapy and is often discontinued, compression bandaging is the best measure to eliminate one of the most essential causes of venous and ulcer disease: namely, the backlog of blood in the veins. However, angiological diagnostics should definitely be performed beforehand!

The Klug-entscheiden-Empfehlung (KEE): “Before a complex wound therapy of chronic leg ulcers a vascular diagnostic (arterial and venous) status should be performed” is intended to support physicians in their responsible work with regard to the correct indication for internal diseases. Dr. Katja Mühlberg, a specialist in internal medicine and angiology at Leipzig University Hospital (D), adds “lymphatic status” at this point because, according to Mühlberg, the stromal bed is often forgotten, although it should be considered in wound diagnostics in particular. Unfortunately, this is not the case in everyday clinical practice: “Newer and more interesting methods are always being tried, such as the newly published guideline on cold plasma application. However, if the cause of the wound is not known, these methods usually do not help. Hippocrates already knew this and his statement “The gods put the diagnosis before the therapy” is still valid today,” says Mühlberg [1].

Angiological diagnostics

The causes of leg wounds are approximately 80% in the angiological field. This concerns the arterial, venous, and lymphatic area as well as the diabetic-neuropathic area, since neuropathy is classified as microangiopathy in the vascular diagnosis. Regardless of wound dressings, arterial perfusion defects, which often end in gangrene or dry necrosis, must be revascularized. Leg ulcerations due to congestion, whether venous or lymphatic in origin, should be decompressed. And diabetic neuropathic pressure-related ulcerations need pressure relief. In addition, according to the guideline, patients with non-healing wounds should receive pAVD screening using an ankle-brachial index (ABI). Wounds are described as non-healing if they do not show any healing tendency even after four to six weeks.

Lack of compliance with guidelines a problem

However, notwithstanding recent advances in pAVD treatment, current outcomes remain poor, particularly in critical limb ischemia (CLI). Despite the demonstrated reduction in limb loss with revascularization, CLI patients still receive significantly fewer angiographies and revascularizations. This is confirmed by data from a Münster study group showing that 37% of all patients going for amputation have never previously attempted vascular imaging or revascularization [2]. In addition, female patients with chronic extremity-threatening ischemia are treated significantly worse than male patients. According to study results, they are less likely to undergo a revascularization attempt and they are also less likely to receive guideline-adherent therapy [3].

Stasis-related wounds (venous and lymphatic causes)

The diagnosis of stasis-related wounds is usually performed by visual diagnosis; rarely, instrumental diagnosis is necessary. Venous causes include chronic venous insufficiency, which is indicated, for example, by varicose veins, thrombosis or post-thrombotic syndrome, which is one of the main causes of venous stasis ulcers. Rather rarely, venous function diagnostics are used; most often, a tomographic procedure is used or ultrasound is used when patients are unable to provide information or the findings are inconclusive.

Venous edema results predominantly from venous valvular insufficiency, which causes pendulum flow. They present as a result of varicose veins or proximally located thrombosis in the pelvic/thigh area, where backwater occurs. At this point, Mühlberg again draws attention to the third flow area in angiology, the lymphatic vessels. In the interstitial tissue, these are closely coupled with the capillaries and arterio-venous connections and play a major role, especially in congestion-related lesions. Contrary to the previous assumption of the Frank-Starling mechanism, 90% of lymphatic drainage or interstitial fluid is removed via the lymphatic vessels, independent of pressure gradients. If venous congestion is present, as in post-thrombotic syndrome, the system is overloaded many times over.

Lymphatic causes include surgery, radiation or tumors, which can lead to lymphedema. Chronic venous congestion in particular is a more frequent starting point for lymphedema. Arthrogenic stasis systems, which occur, for example, during immobility when the ankle joint can no longer be actively moved, are also typical triggers of lymphedema and lymphedematous ulcerations. Not to mention obesity. Obesity-associated lymphedema is on the rise, and neuropathic lymphedema may also occur. These also play a role in diabetic foot syndrome. This is because in diabetics there is permanent vasoconstriction in the precapillary sphincter due to neuropathy. For this reason, the blood does not enter the end-stream pathway, but makes a short circuit across AV shunts. However, the end-stream pathway is part of the region where wound healing occurs and is sensitive to pressure loads.

Perform compression history

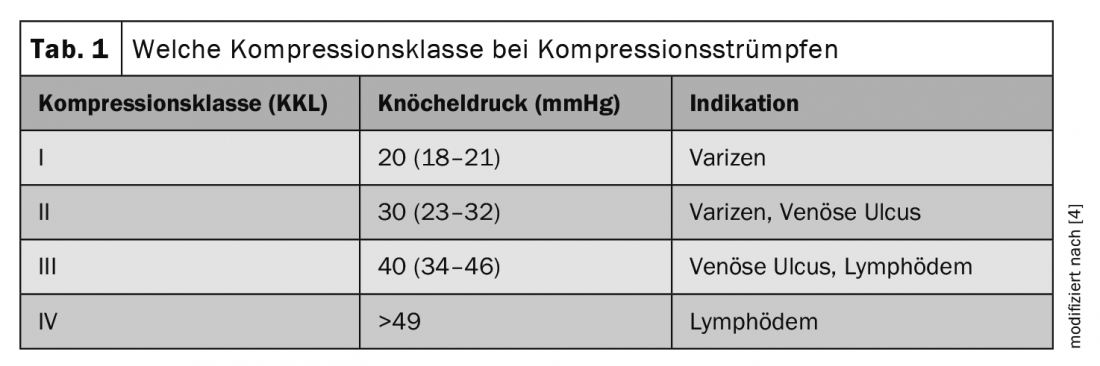

When diagnosing wounds with venous and lymphatic ulcers due to congestion, a compression history is always included. A compression bandage pressure should be about 40-50 mmHg for chronic venous or lymphatic ulceration. This is achieved by professionals in about 12% of all patients. Most compression bandages are well below the target pressure. In addition, classic venous compression stockings should not be used in the treatment of chronic venous or lymphatic ulcerations. The correct stocking in this case is the flat knit. The compression class should be at least class two. Compression class three should be prescribed for more extensive larger lesions (Table 1) [4].

Practical implementations in wound consultations

Muehlberg says every patient with a wound in her practice gets an ankle-brachial pressure measurement. Firstly, to find out whether there is a masked or non-masked arterial perfusion deficit, and to clarify how much compression is allowed. Pathologic ABI is followed by vascular ultrasound and catheter revascularization, if necessary. Since wound healing can only take place if the tissue is reasonably nourished. In venous ulcerations, the search for risk factors such as chronic venous insufficiency or postthrombotic syndrome is performed. In the case of lymphedema, the history is crucial, as is follow-up with tape measure circumference control. Neuropathy screening is also performed if necessary, as well as diabetic foot syndrome testing. Underlying diseases should not be ignored, as not everything is vascular or solely vascular, as well as the patients’ nutritional status, Mühlberg recommends.

Take-Home Messages

- Always ABI measurement/vascular ultrasound

- Think about masked pAVK

- No amputation without vascularization/revascularization attempt

- Without revascularization, the arterial ulcer does not heal

- Without (effective) compression, the venous/lymphatic ulcer does not heal

- Without relief, diabetic neuropathic ulcer does not heal

Congress: DGIM

Literature:

- Katja Sibylle Mühlberg: Klug entscheiden in der Angiologie: Chronische Wunden – nie ohne Gefäßdiagnostik. 12th DGIM Interactive Case Discussion, 04/30/2022.

- Reinecke H, et al: Peripheral arterial disease and critical limb ischaemia: still poor outcomes and lack of guideline adherence. Eur Heart J 2015; doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehv006.

- Makowski L, et al: Sex-related differences in treatment and outcome of chronic limb-threatening ischaemia: a real-world cohort. Eur Heart J 2022; doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehac016.

- Lurie F, et al: Compression therapy after invasive treatment of superficial veins of the lower extremities: Clinical practice guidelines of the American Venous Forum, Society for Vascular Surgery, American College of Phlebology, Society for Vascular Medicine, and International Union of Phlebology. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphatic Disord 2019; doi: 10.1016/j.jvsv.2018.10.002.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2022; 17(6): 32-33