115 years ago, the first synthetically produced analgesic came onto the market in a shelf-stable form. This was acetylsalicylic acid, which is still in use today. In the meantime, many other products have come onto the market, with synthetically produced opioids in particular bringing great progress in terms of analgesic potency. Still, the problem of pain control is far from solved. The article highlights the therapeutic options currently used in practice and discusses their use based on the different pain mechanisms.

The question of whether the problem of pain control has been solved answers itself every day in the consultations of family doctors and hospitals. The control of acute pain has certainly received a big boost from pharmacologic developments. But even here we are still far from the goal of satisfactory analgesia. The reasons for this are manifold and lie on the side of both patients and physicians [1]. In emergency medicine, temporal latency in administration and anxious restraint are often present as causes of inadequate pain management. Depending on the study, only one-eighth to one-half of patients with lower extremity fractures receive adequate analgesics quickly [2]. Postoperative pain is also still unsatisfactorily treated in the present era despite all the progress made [3, 4].

The situation is much less favorable in the treatment of chronic pain (longer than three months). Across Europe, 19% of the population suffer from chronic pain at some point in their lifetime. Of Swiss pain patients, a quarter have been suffering from chronic pain for more than 25 years. Fifty-four percent reported their pain as uncontrolled, and only 27% of patients ever received prescription medication for this complaint [5].

The economic costs are three times higher than those of bronchial asthma or more than twice those of diabetes mellitus [6]. The fact that pharmacological development has not brought any progress in this field shows that a purely somatic clinical picture is not sufficient to explain these chronic complaints. The multi-layered principle of the bio-psycho-social model is suitable here.

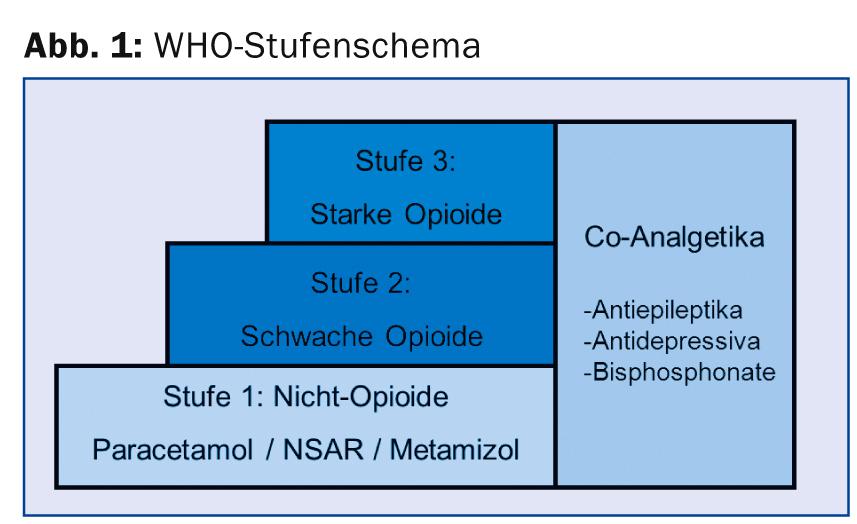

Importance of the WHO stage scheme

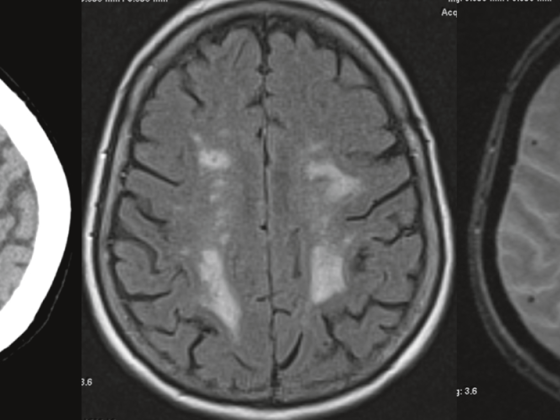

When it comes to drug therapy for pain, many physicians are still guided by the well-known WHO staging scheme (Fig. 1), which recommends a gradual expansion of analgesia. The following three categories are distinguished:

- Non-opioid analgesics

- Weak analgesics

- Strong analgesics

In addition, drugs from the group of antiepileptics, antidepressants, bisphosphonates, steroids or muscle relaxants are grouped under a separate group as co-analgesics. The advantage of this concept is that it provides simple, practical guidance for every physician through the gradual expansion of pain therapy, thus reducing fears and inhibitions that are often present, particularly in the use of strong opioids. This WHO staging scheme was created and validated for use in tumor-related pain, but subsequently found increasing application in non-malignant pain patients.

However, it only considers the intensity of pain as the only criterion of analgesic choice, which can be determined by “visual analog scale” (VAS) or “numeric rating scale” (NRS) [7]. The underlying pain mechanism is not included in the considerations. However, this has a decisive influence on the choice of the appropriate analgesic. Therefore, the staging scheme does not fully reflect the differential diagnostic considerations of pain management that are common today. However, it can still be applied as a rough guide, especially for malignant pain. Particularly in countries where access to opioids is not so easy, the use of the internationally recognized WHO staging scheme is a good aid in the indication and justification for strong opioids.

In addition, there are the general recommendations for the use of pain therapy propagated by the WHO. Compliance with the first two recommendations in particular is important and must be well instructed.

- “By the mouth”: Whenever possible, peroral therapy should be sought. Other forms of application have their place, but should only be used in special situations.

- “By the clock”: the timing of taking the medication should be based on its duration of action, not on external circumstances such as meals. Otherwise, you risk pain spikes.

- “By the ladder”: the current significance of the WHO staging scheme has already been discussed.

Pain therapy according to pain mechanism

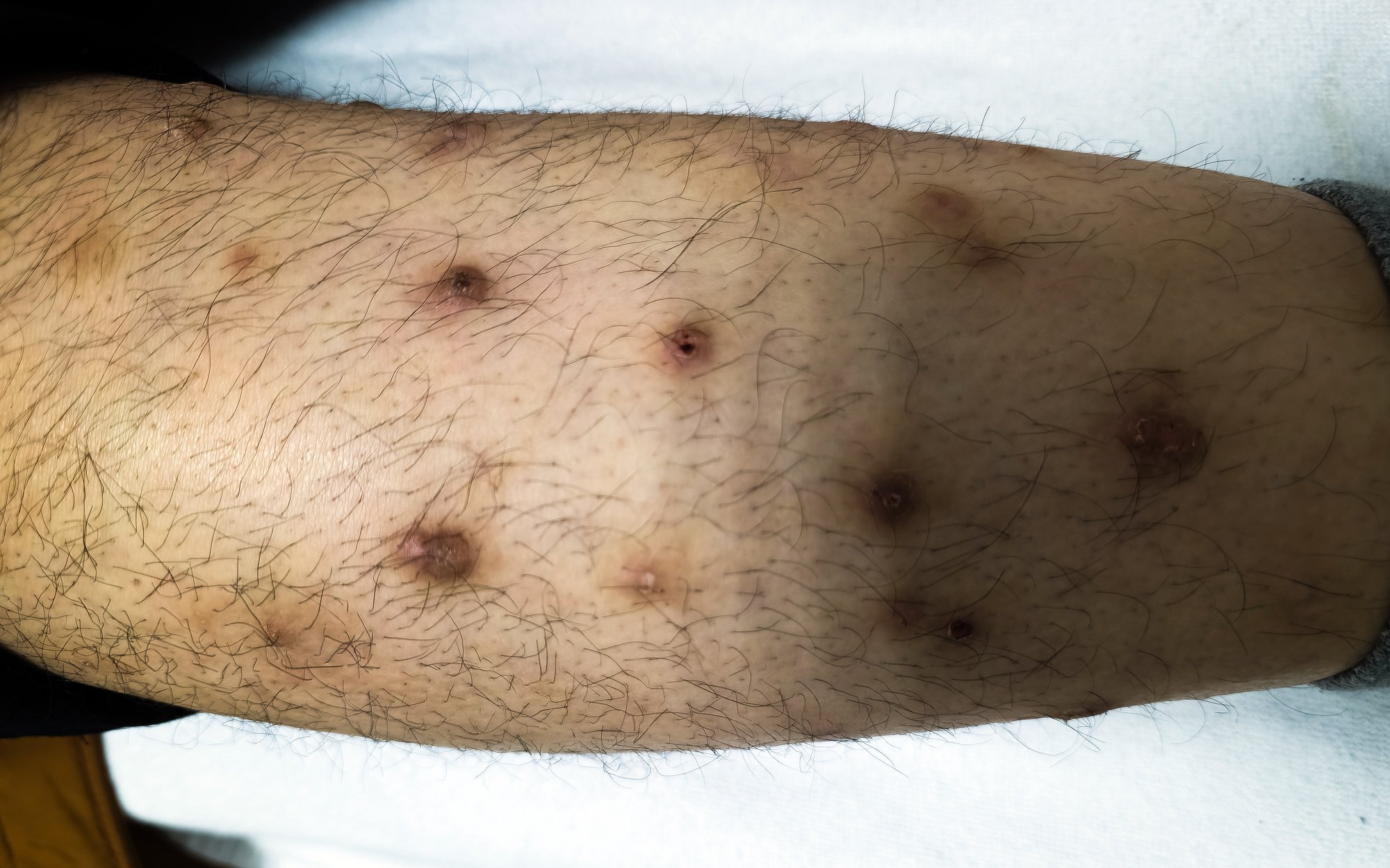

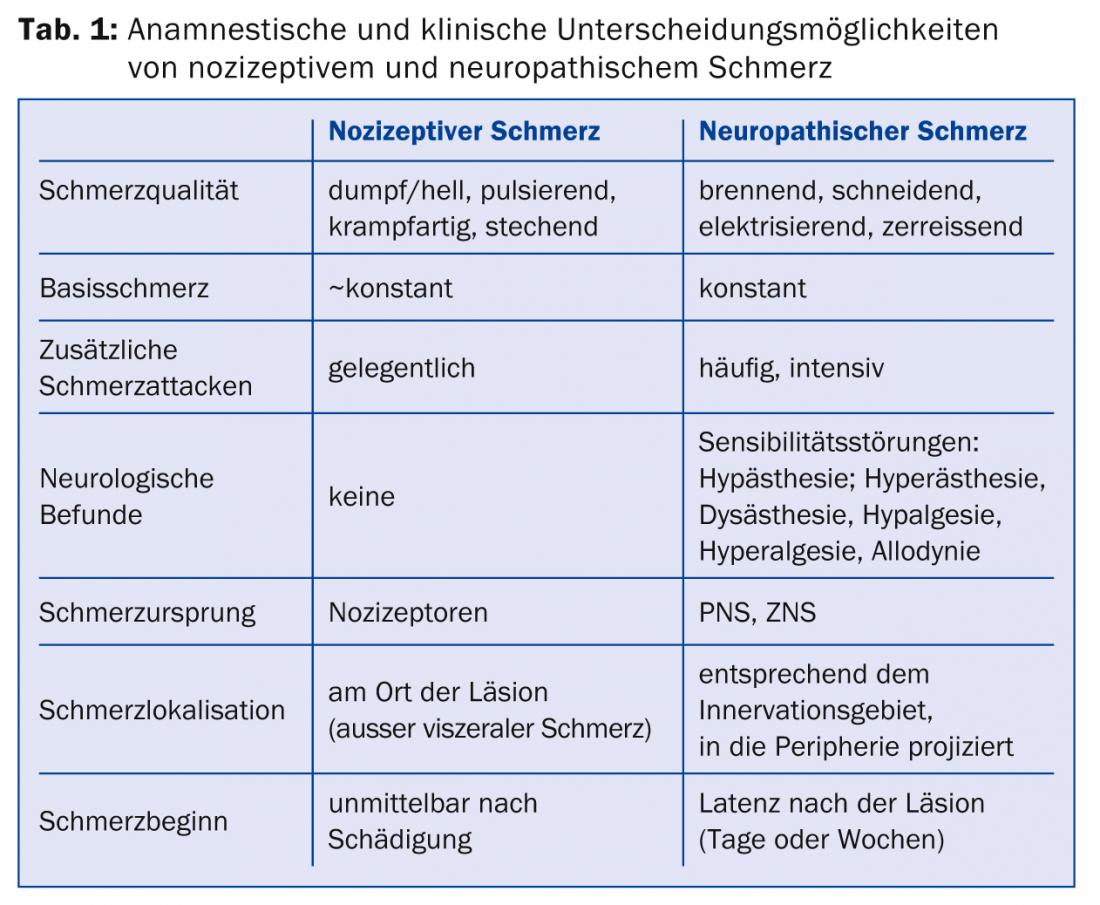

To begin targeted pain management, one must be aware of the characteristics of the different types of pain so that one can identify them [8]. It is mainly divided into nociceptive pain (somatic, visceral), neuropathic pain and mixed nociceptive-neuropathic pain (Table 1) .

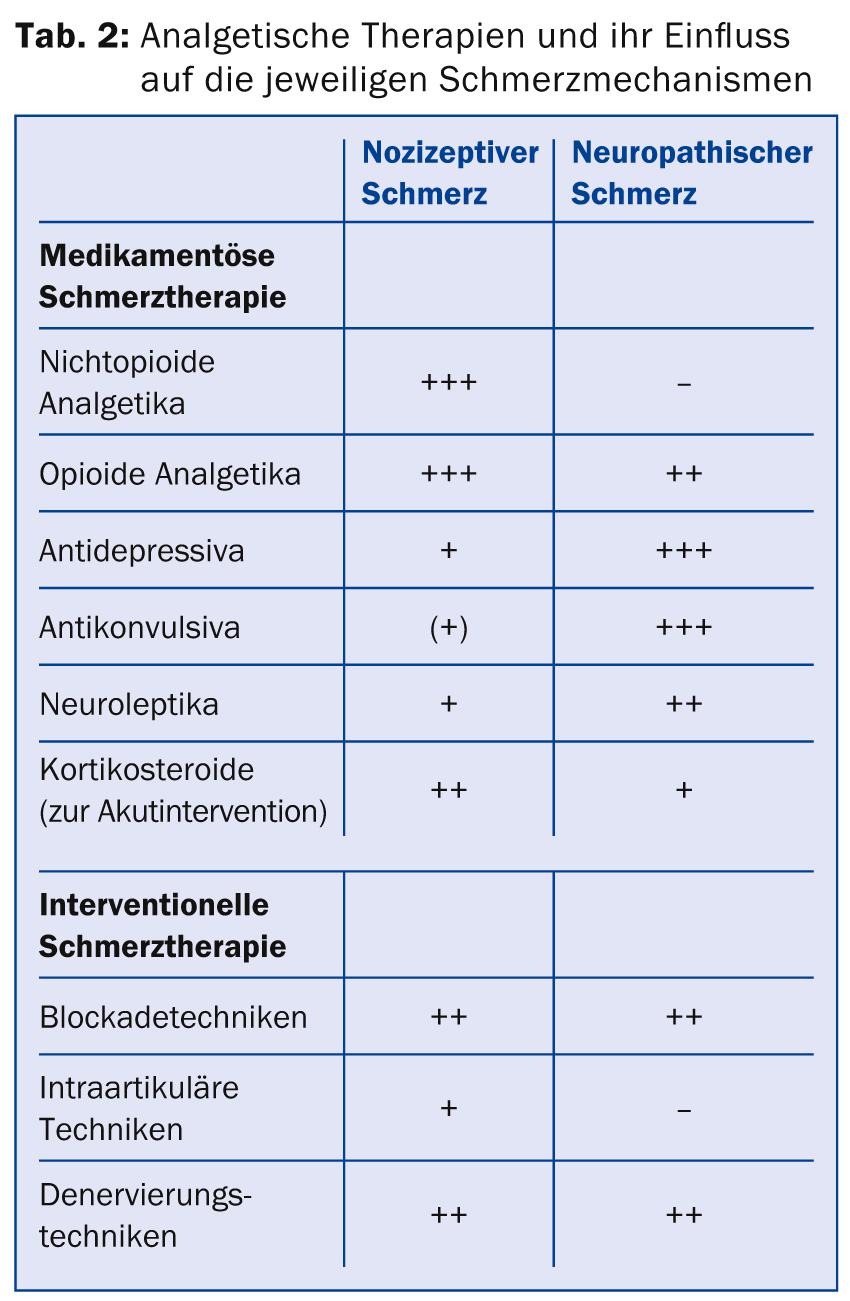

This classification can have a direct influence on the choice of analgesic (Table 2) . For example, neuropathic pain does not respond to WHO level 1 peripheral analgesics. An inflammatory pain will in all likelihood respond best to an anti-inflammatory drug. Nowadays, the treating physician should increasingly include such considerations in his therapy. If one then additionally considers a patient’s secondary diagnoses and non-analgesic therapy with the “drug-disease” and “drug-drug-interactions” that must be taken into account, it becomes clear why sophisticated drug therapy for pain is not a trivial issue.

Pain types represent the specification of a symptom, not a diagnosis. The classification of a pain must be followed by the search for the cause of the pain. This includes, even in the chronic pain patient who has been evaluated by many physicians, a careful history, clinical examination, and study of all available prior examinations and prior reports.

Nociceptive pain

The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) defines nociceptive pain as pain that results from actual or impending damage to non-neuronal tissue and is triggered by activation of nociceptors [9]. Characteristically, this pain is described as bright, stabbing or cramping. It is usually easily localized and occurs at the site of the lesion, although this is limited for visceral pain. Unlike neuropathic pain, there are no accompanying neurologic symptoms.

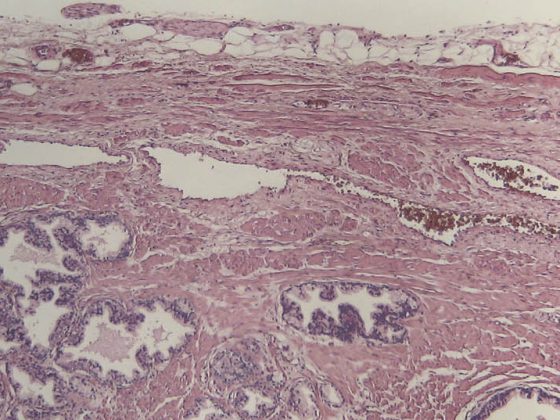

Neuropathic pain

This type of pain is defined by the IASP as pain resulting from a lesion or disease of the somatosensory nervous system [9]. It can be divided into central and peripheral neuropathic pain, depending on where the cause of the pain is located. Typically, patients describe it as burning, cutting, electrifying, or tearing, often with a shooting-in character. Pain can often be projected to the periphery due to the corresponding innervation area represented by the damaged nerve, making it more difficult to localize. It will often be accompanied by neurological findings in terms of plus or minus symptoms. These include hypesthesia, dysesthesia, hypalgesia, hyperalgesia, or allodynia.

Mixed pain

Mixed pain is a combination of the above-mentioned types of pain with their corresponding elements. Many types of tumor pain or even back pain fall into this category.

Features of acute pain

Acute pain has the sense of a warning symptom and is intended to prevent us from straining a damaged part of the body. It can lead to hyperglycemia, catabolic metabolism, tachycardia, hypertension, and vasoconstriction via sympathetic activation and an adrenocortical stress response. Avoidance behavior as well as increased muscle tone may result in limited mobilization with deconditioning, increased risk of thromboembolic events, and hypoventilation. Poorly controlled pain increases the risk of delirium, especially in elderly patients, leading to increased morbidity and mortality. Even without the complication of delirium, the average length of hospitalization is increased in patients with poorly controlled pain. Inadequate treatment of acute pain is also one of the main risk factors of chronicity of pain.

All of this illustrates why satisfactory pain control, while primarily a service to the patient in terms of promoting well-being, is secondarily a prevention of complications and secondary problems.

Special features of chronic pain

In chronic pain, the function as a warning symptom has been lost. It is important for the physician and patient to set realistic therapy goals. Often, freedom from pain cannot be achieved, which should be communicated from the beginning. Otherwise, disappointment over missed targets will lead to a loss of confidence. In addition to pain reduction, the therapy goal should primarily be to promote mobility and activity. This has a positive impact on psychiatric illnesses such as depression as well as on quality of life and return to work.

Malignant versus non-malignant pain

The approach and communication should be different for patients with chronic tumor pain than for patients with chronic nonmalignant pain. The use of strong opioids is usually unavoidable in the tumor patient, as they are the most effective analgesics and have an effect on both nociceptive and neuropathic pain. Patients often need to have their fear (not respect!) of these medications removed. With careful use with gradual dose adjustment (maximum 30% daily increase in the fixed daily dose) and adequate use of reserve doses to treat pain peaks (10-15% of the fixed daily dose prescribed), the risk of overdose is very low.

For nonmalignant pain, the use of strong opioids is controversial [10]. If they are used, only sustained-release forms should be used in chronic pain patients, where the potential for addiction is extremely low. The goal of potent analgesia should be primarily to improve mobility, only secondarily to relieve pain. This should also be discussed with the patient prior to use of the medication and consequences defined if these goals are not met, for example, complete discontinuation of strong opioids. The patient is taught that there is an upper dose limit by which an effect should have occurred, that the potential for addiction is great, and that these are the strongest analgesics that exist.

Complementary therapies

The use of drug pain management, when used correctly, is usually effective, safe, and well tolerated. In addition, however, other, non-medicinal therapies and measures should not be forgotten, which are also helpful for pain patients. First of all, the valuable patient-doctor relationship should be mentioned, which is already able to significantly influence pain by good patient education, by expressing empathy, by absorbing great fears and by mutual trust [11]. Evidence for physiotherapeutic interventions, spinal manipulations, or acupuncture varies depending on pain location and duration [12].

The consistent application and implementation of the bio-psycho-social model led to the development of multi-week programs with a multimodal approach, in which not only purely somatic elements are treated, but psychological therapies are used in parallel and solutions are also to be sought for social factors [13]. Chronic pain must be addressed in a multimodal fashion. This is a prerequisite for serious pain management.

Dominik Schneider, MD

CONCLUSION FOR PRACTICE

- Modern pain therapy should take into account the pain mechanism, not just the pain intensity.

- The distinction between neuropathic and nociceptive pain has direct implications for analgesic choice.

- Treatment of acute pain not only serves the patient’s quality of life, but also prevents pain chronicity and immediate complications with increased morbidity and mortality.

- When taking analgesics over time, it is essential to take into account the duration of action of the drug.

- Nonpharmacologic therapies for pain reduction, particularly multimodal therapy programs, are evidence-based and sometimes cost-effective.

Literature:

- Theiler R: Swiss Medical Forum 2012; 12(34): 645-651.

- Abbuhl FB, Reed DB: Prehosp Emerg Care 2003; 7(4): 445-447.

- McHugh GA, Thoms GM: Anaesthesia 2002; 57(3): 270-275.

- Kehlet H, Jensen TS, Woolf CJ: Lancet 2006; 367(9522): 1618-1625.

- Breivik H, et al: Eur J Pain 2006; 10(4): 287-333.

- Oggier W: Swiss Medical Journal 2007; 88(29/30): 1265-1269.

- Dworkin RH, et al: Pain 2009; 146(3): 238-244.

- Pergolizzi J: Curr Med Res Opin 2011; 27(10): 2079-2080.

- IASP, Taxonomy Chronic Pain. www.iasp-pain.org/Education/Content.aspx?ItemNumber=1698.

- Gupta S, Atcheson R: J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol 2013; 29(1): 6-12.

- Cherkin DC, et al: N Engl J Med 1998; 339(15): 1021-1029.

- Cherkin DC, et al: Ann Intern Med 2003; 138(11): 898-906.

- Angst F, et al: J Rehabil Med 2009; 41(7): 569-575.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2014; 9(5): 15-18