Tumor-associated fatigue can manifest itself physically, psychologically, and cognitively and is subjectively very distressing. It is recommended to clarify them as early as possible and at reasonable intervals during the course of a disease. If necessary, therapy should be initiated.

Fatigue and exhaustion are the most common and long-lasting secondary problems after tumor disease and are referred to by the technical term “tumor-associated fatigue” (hereafter abbreviated as “cancer-related fatigue”, CrF).

Definition and prevalence data

Fatigue due to tumor disease is consistently characterized in most definitions as a distressing feeling of atypical fatigue and weakness at the physical, emotional, and cognitive levels that is unrelated to physical activity and cannot be significantly improved by rest or sleep [1]. In the current discussion, fatigue due to tumor disease is considered a syndrome and does not represent an independent clinical picture in the sense of the ICD [2]. Tumor-associated fatigue should thus be distinguished from ICD diagnoses known in connection with fatigue problems, such as psychovegetative fatigue syndrome, neurasthenia, or chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS).

The prevalence of tumor-associated fatigue after tumor therapy varies between 60-100%, with data varying between studies depending on how it was recorded and the stage of disease or treatment [1]. Fatigue affects the quality of life of those affected in almost all areas [3] and is a risk factor for occupational reintegration [4].

For tumor-associated fatigue, there is currently no clear pathogenetic explanation of the cause-effect relationships. Therefore, it is thought to have a multifactorial genesis involving the interaction of various factors such as inflammatory cytokines, changes in the pituitary-adrenal axis, metabolic changes, infections, hormonal changes, immunosuppression, drug side effects, and physical inactivity [1]. Cardiac or pulmonary functional limitations have an additional negative impact on fatigue. Likewise, psychological factors such as depression and anxiety are discussed as possible influencing factors [5].

Diagnostics

The diagnosis of CrF aims at the early identification and differentiated recording of symptoms, accompanying complaints, and possible specific causes and influencing factors. A multi-method approach is recommended, which includes the following areas:

- Clinical examination (anamnesis, clarification of somatic factors and comorbidities, physical fitness, etc.)

- Laboratory testing (TSH, anemia, electrolytes, metabolism, etc.)

- Psychological examination (depression, anxiety, coping, psychosocial stress, etc.).

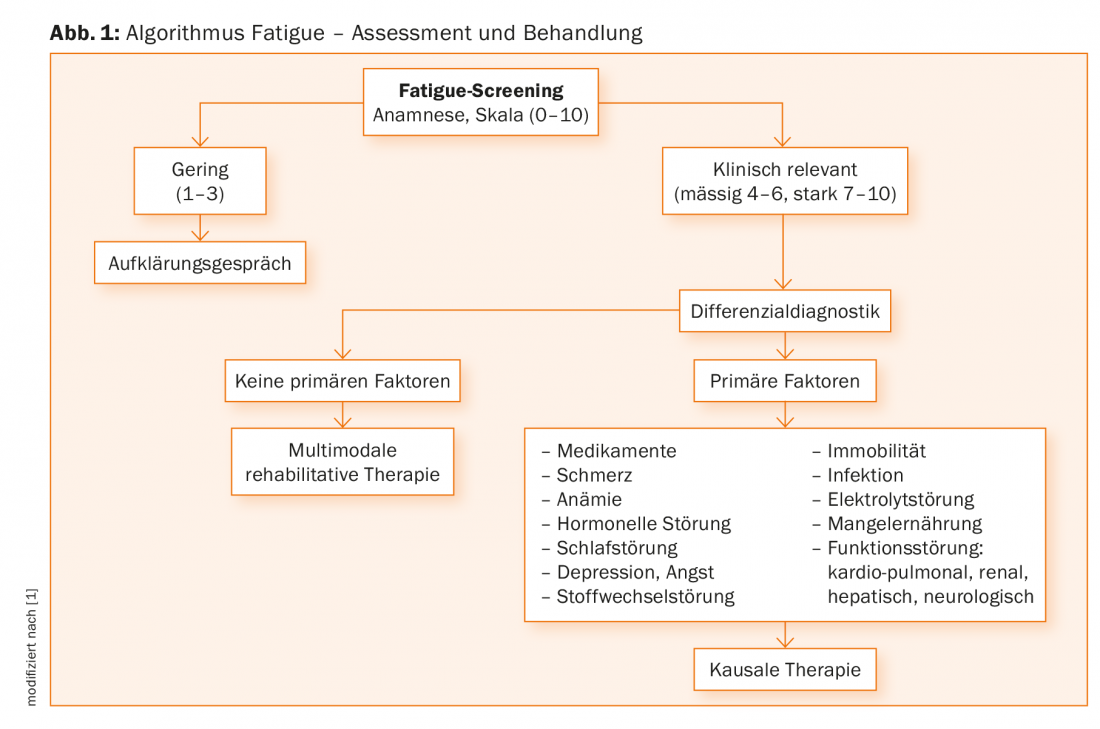

In the diagnosis, possible treatable causes and influencing factors should be identified in a stepwise approach. According to the recommendations of current guidelines [1], patients should be questioned in a first step with regard to CrF using a numerical scale on which the intensity of the complaints in the previous week can be indicated [6]. In the further diagnostic clarification, the anamnestic interview plays a central role [7], in which, among other things, the type, severity, history, and temporal course of the complaints are inquired about. In order to enable a uniform diagnosis, it is recommended to follow the criteria that were developed based on the ICD-10 and have proven to be valid [8]. Figure 1 gives the algorithm for the work-up, diagnosis and initiation of treatment of CrF. Since CrF is primarily assessed by subjective complaints, standardized single- or multidimensional questionnaires are an important source of information in addition to the clinical interview [1]; however, a gold standard for assessing fatigue is not currently available.

Treatment

Unless treatable physical causes of CrF have been clearly identified, treatment should primarily reduce symptoms, strengthen physical performance, and teach the patient appropriate coping strategies. Treatment is always based on the status of the tumor disease, the comorbidity and the extent of the individual complaints or functional impairments. As a general rule, CrF should be treated as early as possible to counteract chronification. Today, the main treatment options available are physical training, psychosocial therapy approaches, mind-body interventions, and medications.

In the area of physical training, endurance and strength training programs are designed to stop the vicious circle of lack of exercise, loss of fitness and rapid exhaustion, or to restore performance. Physical exercise can be recommended to patients with CrF, provided there are no contraindications (these include cardiovascular disease, for example). Physical training through strength and/or endurance training to improve CrF shows very good evidence [9].

Psychosocial interventions include psychosocial counseling, psychotherapy, psychoeducation, and mind-body procedures aimed at reducing CrF through behavioral strategies or positively influencing it by changing subjective experience [10].

Strategies of information and counseling primarily refer to the transfer of knowledge regarding the development of fatigue, its influencing factors and the subjective possibilities of influence. Psychoeducational interventions can be offered as individual or group interventions and provide information and counseling as well as active instruction and structured tasks aimed at promoting and strengthening self-management [11]. Scientific studies evaluating psychoeducational programs show that this can reduce fatigue with small to moderate effect sizes [10]. Psychosocial interventions can also be combined with physically oriented exercise programs [12].

The term mind-body interventions encompasses approaches designed to promote and strengthen active and health-promoting strategies of the patient with the overall goal of improved self-care. To improve CrF, based on the available studies, especially mindfulness-based practices [13] and yoga [14] can be recommended.

Drug therapy of CrF aims to mitigate the influence of specific factors such as anemia, malnutrition, sleep or endocrinological disorders. In addition, attempts are made to act on possible pathogenetic factors, such as CNS dopaminergic and serotoninergic systems and those of central energy homeostasis. The use of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs) may reduce the symptomatology of CrF in anemic patients during chemotherapy. However, the expected treatment effect is usually not strong [15]. Intervention studies with antidepressants from the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) group, such as paroxetine, have not yet shown specific efficacy on CrF [16]. Psychostimulants such as methylphenidate may reduce symptoms, but heterogeneous results of studies suggest very cautious use [15]. From the field of naturopathic treatment strategies, primarily medicinal ginseng preparations can be used based on the study situation, although there is still a high need for research here as well [17].

Take-Home Messages

- Tumor-associated fatigue is the most common sequelae of tumor disease and tumor treatment and can manifest as physical, psychological, and cognitive symptoms.

- Fatigue symptoms are subjectively distressing and can significantly limit an individual’s quality of life, daily living, and job performance.

- Fatigue is multicausal and its cause-effect relationships have been poorly elucidated to date.

- It is recommended to clarify fatigue as early as possible and at reasonable intervals during the course of an illness in a graduated diagnostic process in order to be able to initiate early therapy if necessary.

- Various therapeutic approaches exist to alleviate fatigue, with the best therapeutic successes expected from a multimodal therapy concept.

Literature:

- NCCN (National Comprehensive Cancer Network): Clinical practice guidelines in oncology: cancer-related fatigue. Version 2. 2018. www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/fatigue.pdf.

- Heim M, Weis J: Fatigue in tumor diseases: Recognition, Treatment, Prevention. Stuttgart: Schattauer 2015.

- Pachman DR, et al: Troublesome Symptoms in Cancer Survivors: Fatigue, Insomnia, Neuropathy, and Pain. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2012; 30: 3687-3696.

- Mehnert A: Employment and work-related issues in cancer survivors. Crit Rev Oncol Hemat 2011; 77: 109-130.

- Brown LF, Kroenke K: Cancer-related fatigue and its associations with depression and anxiety: a systematic review. Psychosomatics 2009; 50: 440-447.

- Alexander S, Minton O, Stone PC: Evaluation of Screening Instruments for Cancer-Related Fatigue Syndrome in Breast Cancer Survivors. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27: 1197-1201.

- Horneber M, et al: Tumor-associated fatigue. Deutsches Ärzeblatt 2012; 109: 161-171.

- Donovan K, McGinty H, Jacobsen P: A systematic review of research using diagnostic criteria for cancer-related fatigue. Psycho-Oncol 2013; 22: 737-744.

- Buffart LM, et al: Evidence-based physical activity guidelines for cancer survivors: current guidelines, knowledge gaps and future research directions. Cancer Treat Rev 2014; 40: 327-340.

- Goedendorp MM, et al: Psychosocial interventions for reducing fatigue during cancer treatment in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009; (1): CD006953.

- de Vries U, et al: Fatigue individuell bewältigen (FIBS): Schulungsmanual und Selbstmanagementprogramm für Menschen mit Krebs. Bern: Huber 2011.

- Du S, et al: Patient education programs for cancer-related fatigue: A systematic review. Patient Educ Couns 2015; 98: 1308-1319.

- Shennan C, Payne S, Fenlon D: What is the evidence for the use of mindfulness-based interventions in cancer care? A review. Psycho-Oncology 2011; 20: 681-697.

- Cramer H, et al: Yoga for improving health-related quality of life, mental health and cancer-related symptoms in women diagnosed with breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017 Jan 3; (1): CD010802.

- Minton O, et al: Drug therapy for the management of cancer related fatigue. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010; (7): CD006704.

- Qu D, et al: Psychotropic drugs for the management of cancer-related fatigue: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer Care 2016; 25: 970-979.

- Greenlee H, et al: Clinical practice guidelines on the use of integrative therapies as supportive care in patients treated for breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst Monographs 2014; 50: 346-358.

Further reading:

- Mosher CE, et al: Physical, psychological, and social sequelae following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a review of the literature. Psycho-Oncology 2009; 18: 113-127.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2018; 16(5): 46-48.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2018; 6(4) 4-6.